Author: Mike Neville

As a type of wine, mead is typically quite strong, with an alcohol range of anywhere from 12 to 15%; however, there’s also a lighter version of this traditional honey wine called hydromel, which boasts alcohol levels more familiar to beer drinkers at 4 to 7%. Due to the general absence of certain nutrients in honey such as nitrogen, meadmakers often rely on exogenous nutrient additions to ensure healthy and robust fermentations.

Whereas with beer, nutrients are typically added to the wort towards the end of the boil step, mead isn’t usually boiled, so nutrient additions are often made directly to the must at the time of yeast pitch. However, many claim that staggered nutrient additions (SNA), a method that involves making a series of up to 4 smaller nutrient additions at planned intervals, typically every 12 hours. The purported benefits of SNA is that by providing nutrients to the yeast when they’re most in need, they’re able to more efficiently use those nutrients, thus improving fermentation activity.

I don’t make mead very often, but with summer approaching, a crushable low ABV hydromel sounded really nice to me. Given the higher strength of standard mead, SNA makes sense to me, though I began to wonder of the impact it might have on a more sessionable hydromel and designed an xBmt to test it out!

| PURPOSE |

To evaluate the differences between a hydromel where the nutrient addition was made entirely at yeast pitch and one where the nutrients additions were staggered over time.

| METHODS |

For this xBmt, I went with a very simple hydromel recipe consisting of just honey, water, yeast, and of course, nutrients.

Viking’s Table

Recipe Details

| Batch Size | Boil Time | IBU | SRM | Est. OG | Est. FG | ABV |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5 gal | 0 min | 0 | 1.5 SRM | 1.04 | 0.98 | 7.88 % |

| Actuals | 1.04 | 0.98 | 7.88 % | |||

Fermentables

| Name | Amount | % |

|---|---|---|

| Clover Honey | 5.5 lbs | 100 |

Miscs

| Name | Amount | min | Type | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fermaid-O | 8 g | 0 min | Primary | Other |

| Go-Ferm | 7.5 g | 0 min | Primary | Other |

Yeast

| Name | Lab | Attenuation | Temperature |

|---|---|---|---|

| Napoleon (B64) | Imperial Yeast | 83% | 32°F - 32°F |

Notes

| Honey blended with tap water treated with Campden tablet |

Download

| Download this recipe's BeerXML file |

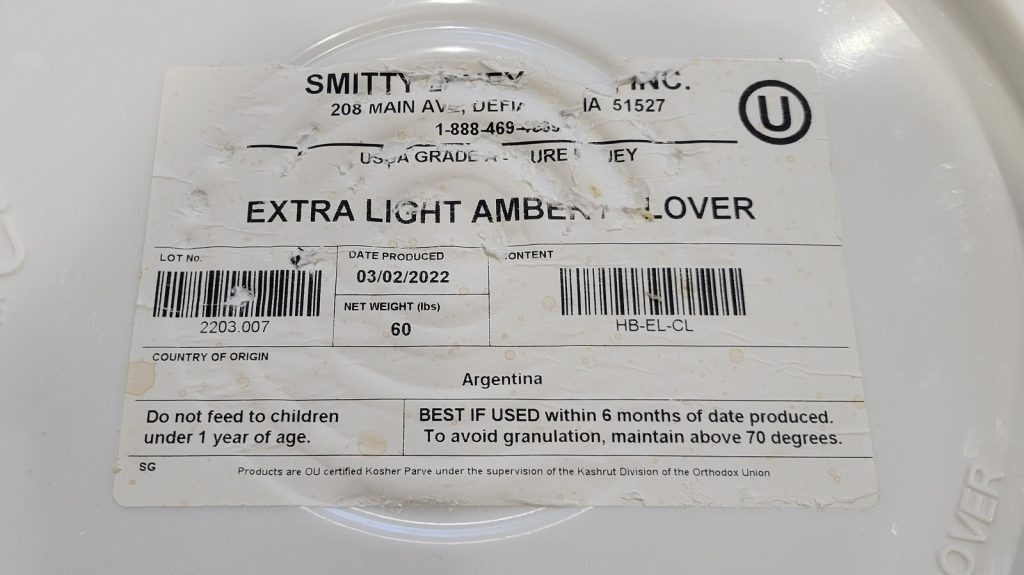

Unlike my typical brew days, making this hydromel would require far less effort. I started off by acquiring a good amount of clover honey.

For each batch, I weighed out 5.5 lbs/2.5 kg of honey in separate fermenters before adding 5.5 gallons/21 liters of water.

I then used a drill mixer to ensure both were adequately homogenized.

Refractometer readings showing both musts were at the same 1.040 OG confirmed my measurements were on point.

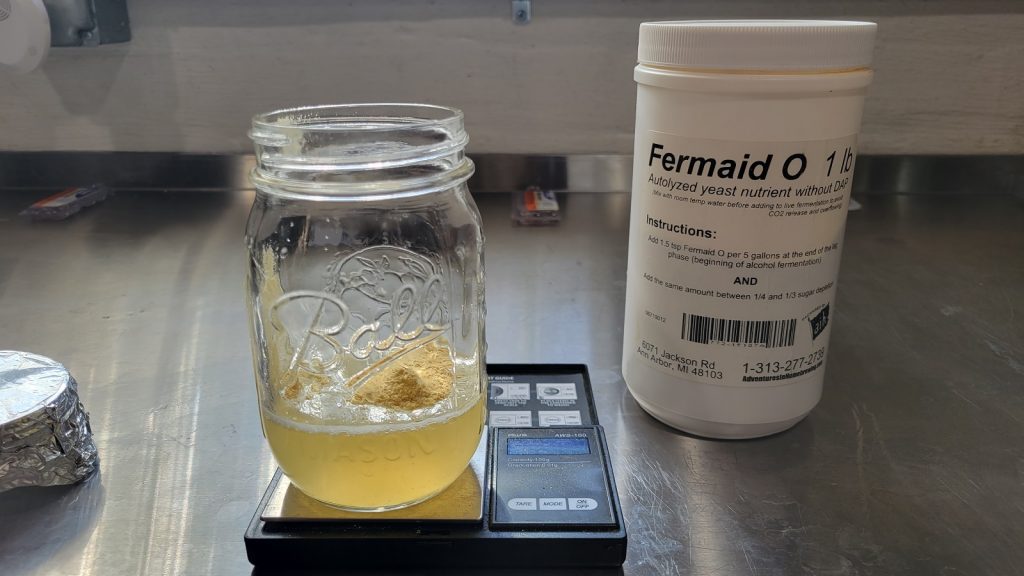

At this point, I pulled 150 mL of must from each batch, adding 7.5 g of Go-Ferm and the entire 8 g of Fermaid-O to one, while the other received the same amount of Go-Ferm with just 2 g of Fermaid-O. Despite opting for liquid yeast for this xBmt, I used Go-Ferm, as a matter of course; seeing as it is a rehydration nutrient, additions are not staggered.

After the nutrients were fully dissolved, I added them back to their respective musts then immediately pitched a pouch of Imperial Yeast B64 Napoleon into each.

The hydromels were connected to my glycol chiller that was controlled to 68°F/20°C. The batch that received the full dose of nutrients was left alone throughout fermentation. For the SNA batch, I dissolved 2 g of Fermaid-O in 100 mL of fermenting hydromel and added it back to the fermenter every 12 hours for a total of 3 additions, which amounted to the same 8 g that was added to the other batch up-front.

With both batches showing an absence of fermentation activity after 15 days, I took hydrometer measurements indicating they reached the same FG.

I proceeded to reduce the temperature of the hydromels to 38°F/3°C and let them cold-crash overnight, at which point they were pressure transferred to CO2 purged kegs.

The filled kegs were placed on gas in my keezer and left to carbonate for 2 weeks before they ready for evaluation.

| RESULTS |

A total of 28 people of varying levels of experience participated in this xBmt. Each participant was served 2 samples of the hydromel where all of the nutrients were added at yeast pitch and 2 samples of the one where nutrients were staggered over time in different colored opaque cups then asked to identify the unique sample. While 15 tasters (p<0.05) would have had to accurately identify the unique sample in order to reach statistical significance, only 12 did (p=0.19), indicating participants in this xBmt were unable to reliably distinguish a hydromel that received the entire dose of nutrients at yeast pitch from one where nutrients were staggered over 36 hours.

My Impressions: Out of the 5 semi-blind triangle tests I attempted, I correctly identified the unique sample just once. To me, these hydromels were identical in every way, both possessing a mild honey flavor that maintained a perception of sweetness despite how dry they were. The lower alcohol combined with the carbonation made this quite refreshing.

| DISCUSSION |

While highly fermentable on its own, honey does not naturally have the nutrients necessary for healthy fermentations, namely nitrogen, which is why meadmakers commonly rely on exogenous nutrient additions. While some add all of their nutrients at yeast pitch, others claim that splitting the additions up over time have added benefits that can result in a higher quality product. Tasters in this xBmt were unable to reliably distinguish a hydromel where all of the nutrients were added up front from one where they were staggered over time.

While these results align with those from past xBmts looking at the perceptible impact yeast nutrients have on cider and beer, one thing consistent between them is that they focused on moderate OG fermentations. It’s possible that SNA would have a more noticeable impact in a higher strength mead as opposed to this hydromel, where the yeast was arguably under less stress to begin with.

Over they years, I’ve made a handful of mead variations and have always used nutrients, usually staggering the additions over time based on what I’ve read. Seeing as these results suggest SNA may not have as big of an impact on lower strength hydromel, I’ll likely start adding all nutrients at yeast pitch when making them, though I look forward to repeating this xBmt on a full strength mead in the future.

If you have any thoughts about this xBmt, please do not hesitate to share in the comments section below!

Support Brülosophy In Style!

All designs are available in various colors and sizes on Amazon!

Follow Brülosophy on:

FACEBOOK | TWITTER | INSTAGRAM

If you enjoy this stuff and feel compelled to support Brulosophy.com, please check out the Support page for details on how you can very easily do so. Thanks!

7 thoughts on “exBEERiment | Impact Staggered Nutrient Additions Have On A Hydromel”

This is a bizarre idea to me, so I have to say I was not surprised by the results. I was curious about the idea behind a staggered nutrient addition because it makes no sense to me from a microbiological perspective (at least staggering sugar additions has the idea of reducing osmotic stress behind it), and found the article at the AHA website on the technique. “Some recipes will call for all the nutrients to be added at the time when the yeast is first pitched into the must. This will undoubtedly provide the yeast with the essentials from the get-go, but the key to keeping yeast happy is providing them with all the desired nutrients throughout the entirety of the fermentation process. If adding all the nutrients at the beginning, it is very likely that a lot of the nutrients won’t even be utilized before flocculating out.” Why is it “likely” that if all nutrients are added at the beginning yeast will drop out prematurely, but if the same amount is staggered they will magically stay in suspension? Did anyone study this in a remotely scientific way? Anyway, thanks for the experiment!

I read the last sentence of the passage you quote differently, namely about the *nutrients* (not the yeast, as you seem to read it) “flocculating out” (whatever that mean). So basically, if the stuff is added on day 1 but not needed until day 5, it’s going to drop out before it is needed.

I have no idea whether that may or may not be factually correct and whether those nutrients can even go out of suspension at all; I just wanted to point out that I think you misread that part.

Hope it helps.

From mead makers the rationale I have heard is not about the nutrients floccing out, but rather that you want there to be nutrients available during the entire fermentation, that adding it all up front will result in more being used than needed, leaving none for later, stressing the yeast at that point and creating off flavors.

From Cider makers I have heard that you want to stagger the nutrients to keep activity low and slow, giving only as much as strictly neccesary, thereby avoiding excessive ester formation and volatile apple flavors from being driven out by a vigerous ferment, while still letting the ferment finish without off flavors.

These schemes generally stagger them out over multiple days, up to a week, not just in the first 36 hours. It’s also usually done with higher OG ferments; low OG meads are said to be more forgiving.

I enjoyed this experiment, but I would also be interested in an experiment with a 1.1+ OG mead and a more staggered schedule.

Love your work, great to see mead on the table and a fantastic test case, love to see a DAP Vs Fermaid-o in hydromels and a Mixed nutrient blend(wyeast) Vs Fermaid-O, Plenty of Mead myths to unfog

The tone of this comment is counterproductive. There may be knowledgeable and informative content in the comment but the ranty egoistic tone leads to few reading the comment completely or carefully and fewer will take it seriously.

I followed your recipe and used Voss Kveik instead of Napoleon and brewed at 80-90 degrees and it was outstanding!

Low ABV meads and meads using a very fast fermenting yeast with Kveik don’t really see any benefits to doing TOSNA. Just pitch all up front. This has been a recommendation in Modern Mead Makers for a while now.

I want to suggest to try re-running the test doing a Sack strength or Standard strength mead. You might see better results.

One thing as well, if temperature control is involved, yeast activity can be slowed and managed better so it doesn’t eat up all the nutrients, get super active and hot up front which can cause off flavors.

Using Ferm-O is a good choice, yeast tend to burn through it slower than Ferm-K or 100% DAP.

There are some really good scientific examples that Bill from Lost Cause and White Labs in San Diego ran on the different type of nutrients and I believe schedules in the AMMA that are interesting to read.