This xBmt was completed by a member of The Brü Club as a part of The Brü Club xBmt Series in collaboration with Brülosophy. While members who choose to participate in this series generally take inspiration from Brülosophy, the bulk of design, writing, and editing is handled by members unless otherwise specified. Articles featured on Brulosophy.com are selected by The Brü Club leadership prior to being submitted for publication. Visit The Brü Club website for more information on this series.

Author: Cade Jobe

Like many homebrewers, the first beer I brewed used dry yeast from an unmarked package that I sprinkled directly into the fermentor. The beer was drinkable (Holy chemistry, Batman. I just made beer!), but nowhere near great. What could I do next time to make it better? Looking back now, 6 years after I brewed that first beer, that question feels like Morpheus’ red pill/blue pill dilemma: Should I just accept my “okay” beer or should I see how deep the rabbit hole goes?

Red pill. Every time.

Plenty of brewing texts offer tips, tricks and alleged solutions for making better beer. I’d read over and over again that dry yeast should always be rehydrated before pitching. According to the texts, yeast cell walls that get altered during the yeast drying process could be damaged—sometimes lethally—when direct pitched into unfermented wort. To avoid that, they suggest to gently rehydrate the yeast before pitching. The first paragraph to Lallemand’s recommended rehydration procedure says as much:

Rehydration is a crucial step to ensure rapid and complete fermentation. There are important rules to follow to slowly transition the cells back to a liquid phase. Careful precautions were taken when drying the yeast and the brewer has the opportunity to revert the process to obtain a highly viable and vital liquid slurry.

Lallemand goes on to report a list of issues observed when non-rehydrated yeast was used under certain brewing conditions:

- Longer diacetyl stand

- Longer fermentation time

- Longer lag phase

- Stuck fermentation

- Poor utilization of maltotriose

For these reasons, I used rehydrated yeast in my next few batches with seemingly better results. Later, I went on to use liquid yeast and eventually starters, but I always wondered whether that rehydration step was really necessary.

It’s been 4 years and 208 xBmts since Marshall put rehydrated versus direct pitch yeast to the test, which did not reach a significant result. In this replication xBmt, I set out to brew the same beer following the same procedures as Marshall did the first time around.

| PURPOSE |

To evaluate the differences between a beer fermented with dry yeast pitched directly into the wort and one where the yeast was rehydrated first.

| METHODS |

The recipe for this xBmt was taken from Marshall’s previous xBmt on the same variable with changes made to accommodate for available ingredients and brewhouse efficiency.

Darktoberfest

Recipe Details

| Batch Size | Boil Time | IBU | SRM | Est. OG | Est. FG | ABV |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5.5 gal | 60 min | 23.0 IBUs | 15.2 SRM | 1.051 | 1.012 | 5.1 % |

| Actuals | 1.051 | 1.012 | 5.1 % | |||

Fermentables

| Name | Amount | % |

|---|---|---|

| Munich Malt - 10L | 7.25 lbs | 68.24 |

| Pilsner (2 Row) Ger | 3 lbs | 28.24 |

| Carafa II | 4 oz | 2.35 |

| Melanoiden Malt | 2 oz | 1.18 |

Hops

| Name | Amount | Time | Use | Form | Alpha % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hallertauer Mittelfrueh | 28 g | 60 min | First Wort | Pellet | 4 |

| Hallertauer Mittelfrueh | 14 g | 20 min | Boil | Pellet | 4 |

| Hallertauer Mittelfrueh | 14 g | 5 min | Boil | Pellet | 4 |

Yeast

| Name | Lab | Attenuation | Temperature |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nottingham (-) | Danstar | 75% | 57°F - 70°F |

Notes

| Water Profile : Ca 51 | Mg 21 | Na 38 | SO4 52 | 56 |

Download

| Download this recipe's BeerXML file |

I started my #BruDay by collecting the brewing water and adjusting it to my desired profile.

As the water heated, I weighed out and milled the grains. Once the water hit strike temperature, I mashed in and checked to make sure I hit my intended mash temperature.

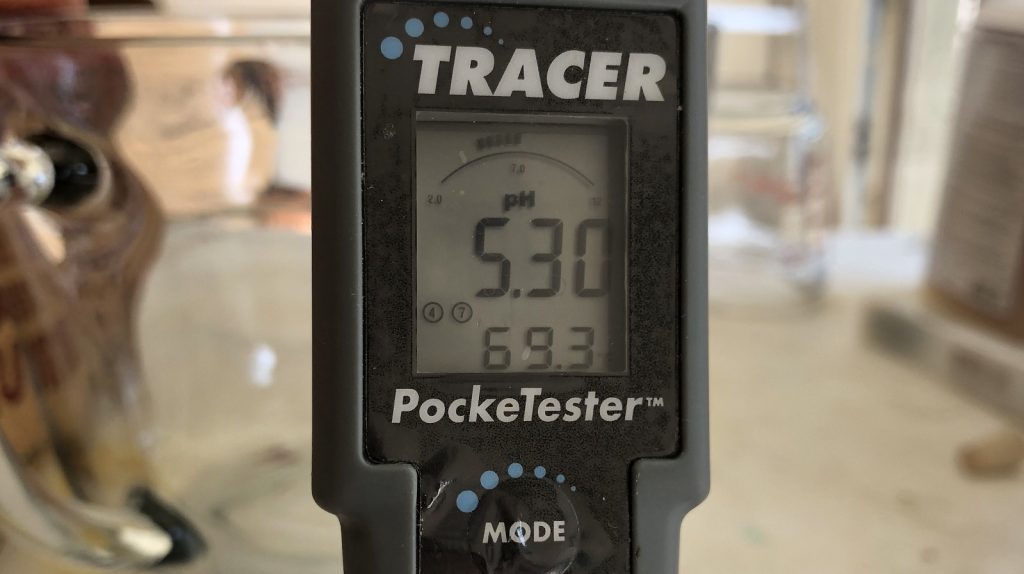

I grabbed a sample of wort about 15 minutes into the mash to check pH.

With the 60 minute mash complete, I performed my standard fly sparge process.

The wort was transferred into my kettle and the first wort hop addition was immediately added.

The wort was boiled for an hour with hops added per the recipe.

Using my custom JaDeD Brewing immersion chiller, I chilled the wort to a few degrees above groundwater temperature.

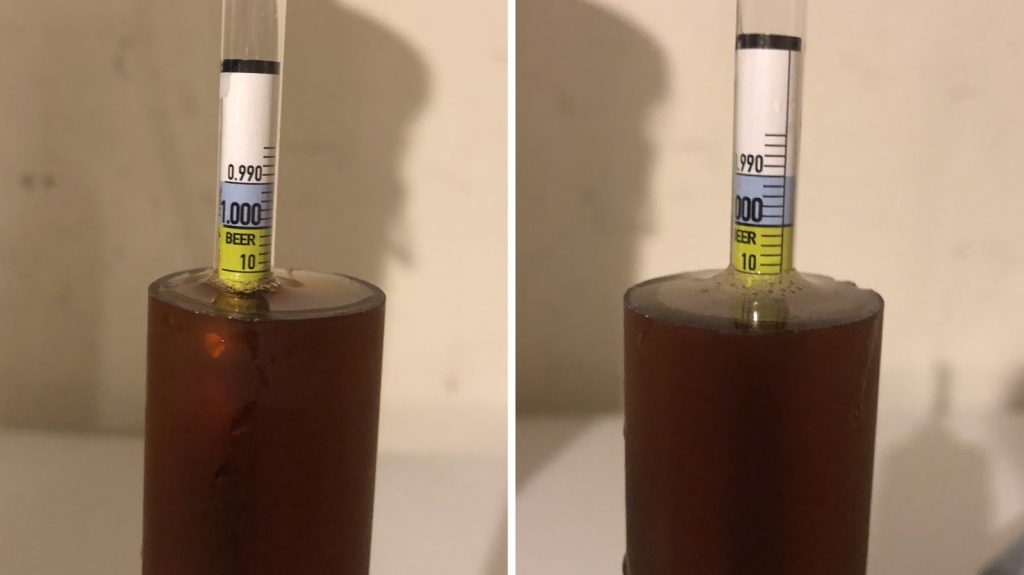

The chilled wort was then split between two identical Ss Brewtech Brew Buckets and set in my fermentation chamber to finish cooling to pitching temperature. A hydrometer measurement showed the wort had reached my intended OG.

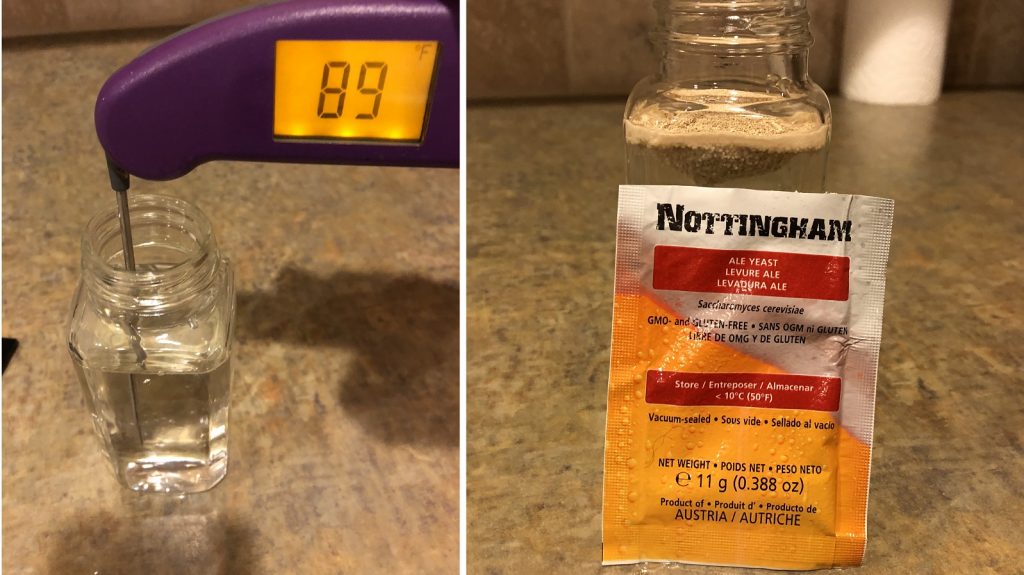

Once the worts were adequately chilled, I rehydrated 1 packet of Nottingham yeast according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

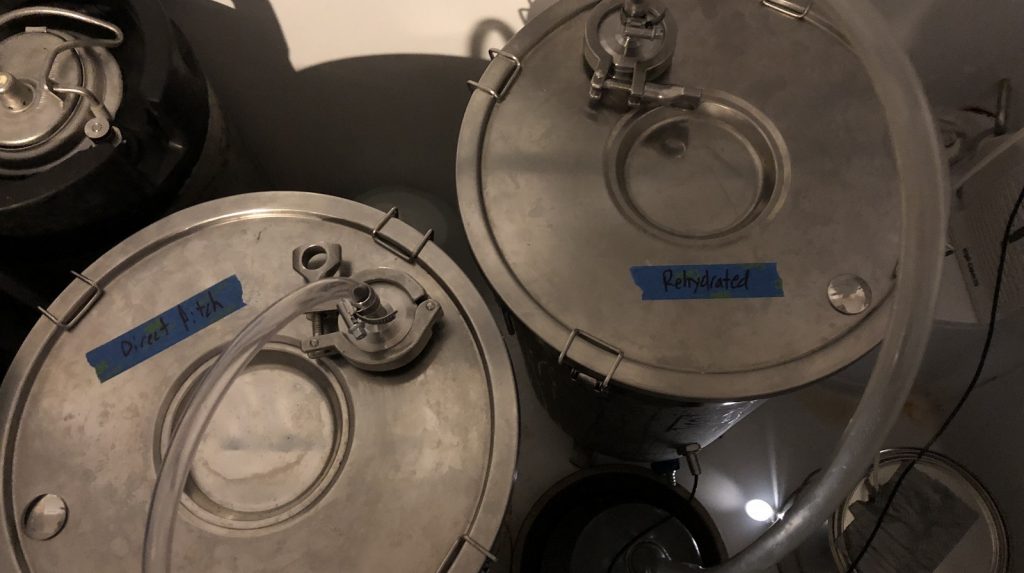

I stirred the rehydrated yeast after 15 minutes and left it for another 5 minutes before pitching the entire slurry into one batch of wort. I then pitched 1 package of Nottingham dry yeast directly into the other wort. Blowoff tubes were attached to both fermentors and they were left alone.

Interested to see if there were noticeable differences during fermentation between the batches, I checked on them 14 hours later and noticed more kräusen formation in the beer pitched with rehydrated yeast.

However, after a full 24 hours, both batches were fermenting vigorously based on airlock activity. I let the beers ferment at 58°F/14°C for 15 days before taking hydrometer measurements confirming both had reached the same FG.

I then pressure transferred the beers to CO2 purged kegs and placed them in my keezer where they were put on gas to carbonate.

After 2 weeks of cold conditioning, the beers were ready to serve to participants.

| RESULTS |

A total of 24 people of varying levels of experience participated in this xBmt. Each participant was served 1 sample of the direct pitch beer and 2 samples of the rehydrated beer in different colored opaque cups then asked to identify the unique sample. While 13 tasters (p<0.05) would have had to accurately identify the unique sample in order to reach statistical significance, only 11 (p=0.14) did so, indicating participants in this xBmt were not able to reliably distinguish a beer made with dry yeast that was directly pitched on the wort from one where the yeast was rehydrated prior to pitching.

My Impressions: Given the results of Marshall’s experiment, I expected to not notice a difference between the beers, and that’s exactly what happened. Out of 4 blind triangle tests, I only picked the odd-beer-out 2 times, and even then I was guessing. Regardless of my focus, attempts to set aside bias, or even beer temperature, the samples were indistinguishable to me. Interestingly, my wife, who was 38 weeks pregnant at the time, consistently identified the unique sample 3 triangle tests based on aroma alone. I thought the beers tasted great! Not quite as malty as I prefer Munich Dunkel to be, but noticeably bready and toasty with a light chocolate character. The body was also little thin for my tastes, which I might fix by upping the amount of Munich in the grist.

| DISCUSSION |

Yeast manufacturers are under immense pressure to produce a consistent product. As such, they take great care to ensure each batch of beer that follows the manufacturers’ recommendations produces the intended outcome. Without knowing much about Lallemand’s quality control standards, I would assume they’d want to minimize the number of bad outcomes produced by their yeast. If 1 out of 100 direct pitched batches comes out bad, that’s likely something Lallemand would want to avoid. It stands to reason, then, that Lallemand’s instructions for using dry yeast would aim to create ideal circumstances for the yeast to make great beer, which makes the non-significant results from this experiment all the more interesting. Maybe if this experiment were repeated 100 times, we might see a significant result often enough due to damaged yeast cells from direct pitching. But in my opinion, brewers may want to view these instructions as best practices rather than prescriptive ones– and make your own decisions from there.

A scientist described significance to me as an astonishment factor: “So many people guessed the correct result that I would be astonished if this result was the product of random chance.” It is not conclusive proof that a variable does or does not produce a noticeable effect. It’s possible that future exBEERiments on this variable could yield a significant result. It makes sense that manufacturers would recommend rehydrating yeast as a preventative measure, even if the potential for bad outcomes is unlikely.

Many of the brewing texts that recommend rehydration were written quite awhile ago, and a lot has changed over the years. It’s entirely possible ingredient quality and standard brewing practices have improved such that the dry yeast of today is hardier and less likely to suffer from the potential negative effects of direct pitching. Alternatively, maybe the different pitching methods did produce a difference and tasters simply weren’t able detect it to significant degree. Either way, with my results corroborating Marshall’s initial findings, I’m inclined to continue skip the rehydration step and pitch dry yeast direct directly into the wort, even if it means slightly longer lag.

Cade Jobe is a Certified Cicerone and Certified Beer Judge (BJCP) living in Austin, Texas. He is a member of the Austin ZEALOTS who loves brewing and spending time with his wife, future (human) son, and his current children– two dogs named Juno and Jasper. Follow Cade on Instagram, Twitter, and UnTappd.

Cade Jobe is a Certified Cicerone and Certified Beer Judge (BJCP) living in Austin, Texas. He is a member of the Austin ZEALOTS who loves brewing and spending time with his wife, future (human) son, and his current children– two dogs named Juno and Jasper. Follow Cade on Instagram, Twitter, and UnTappd.

If you have any thoughts about this xBmt, please do not hesitate to share in the comments section below!

Support Brülosophy In Style!

All designs are available in various colors and sizes on Amazon!

Follow Brülosophy on:

FACEBOOK | TWITTER | INSTAGRAM

If you enjoy this stuff and feel compelled to support Brulosophy.com, please check out the Support page for details on how you can very easily do so. Thanks!

46 thoughts on “The Brü Club xBmt Series | Direct Pitch vs. Rehydration With Dry Yeast”

The Dutch homebrew forum also did such tests, with the same results. So that makes at least three datapoints showing the same results.

However, I hate waiting for fermentation to start, so I rehydrate two days beforehand, pitch in a small starter which I drain at the beginning of my brewing evening, add wort again, and shake it now and then throughout the evening so that I am sure that what I pitch is active.

This way I don’t have to worry. I had to wait once for 48 hours before fermentation started. Never again!

I do the same with my dry yeasts. As you stated, it assures vitality and boosts the cell count. I’ve read several places that starters are not necessary for dry yeast and even BeerSmith doesn’t account for dry yeast starters in their cell count calculator. Oh well, it works and I feel better pitching something that shows signs of being able to make little bubbles. 🙂

The shorter lag time you found is enough for me in support of rehydration. It’s such an easy process…why not?

While I admire the methodology, I’m disappointed in this one. An experiment is only as good as it’s design. This one is really confusing except as a start of a wider series, and due to your brewing/industry knowledge could even be interpreted as intentionally obtuse.

You rehydrate yeast to help it get a leg up, due to either (1.) yeast’s condition (2.) the state of the wort it will be facing (3.) insurance against other organisms that want to feed on the sugars. Your test didn’t look at any of these things, and since 2 weeks is a full ferment for many styles, including what you chose, and you spent a lot of time reaffirming that you will have a faster ferment with rehydrated yeast.

It’s known that tossing a packet of yeast in dry will kill a bunch of cells, basically due to environmental shock as the yeasts try hydrate in liquid filled with sugars. However with modern packaging you are talking billions of cells, and losing some will still leave more than enough to deal with a normal ABV and wort conditions. It’s why many manufacturers are now saying to just toss it in unless you have adverse conditions, which you have to be aware of.

Your time and content are your own, but I’d suggest what would have been more helpful, and useful to the community, would be the same experiment while making the wort environment or yeast condition more challenging.

People used to get really, really old yeast — that had smaller initial cell counts — in stuff can kits and other places and rehydrating became the norm because you could greatly reduce the chance of stalled fermentations. You could replicate old, depleted yeast in a variety of ways (eg., expired dry yeast packet, divided in .5 or .25, then divided again with one half given a starter and the rest tossed in dry).

Alternately, you could have made the wort environment more challenging, which is a *far* more likely scenario to any brewer. e.g., you could have done a very high ABV beer, so the yeast was dropped into a high-sugar environment where starters are recommended. You could have fermented out of the yeast’s ideal temperature range. You could also test it’s ability to outcompete other organisms, like wild yeast/etc., via perhaps an open ferment.

You can use sound methodology to test anything, but you have to ask if what you’ll really learn by the effort and if it’s adding real value to what’s known. In this case, we learned your rehydrated starter was able to be up and running quicker, but the parameters made none of the rest matter. I’m hoping you take the next step!

> Your time and content are your own, but I’d suggest what would have been more helpful, and useful to the community, would be the same experiment while making the wort environment or yeast condition more challenging

Can you please link us your more helpful to the community trials? Thanks

It probably wouldn’t make a difference here but it’d be great to do a meta-analysis on any repeated experiments in the future to combine both samples together! It allows you to statistically test for smaller effects – whilst accounting for the fact that brewing the same batch twice wouldn’t necessarily produce a completely identical beer. Could be particularly useful for exbeeriments with p-values very close to the magical 0.05 threshold. It’s commonly used to combine clinical trials from different sites around the globe, for instance.

Did you try the same experiment with a different strain of yeast or maybe a higher fermentation temperature? Wouldn’t the lag time difference and yeast viability influence more the finished beer in those conditions?

Here have a look at what Fermentis published. https://fermentis.com/en/news-from-fermentis/technical-reviews/e2u-direct-pitching/

Fermentis is now recommending direct pitch of their yeasts (they also provide instructions on rehydration if that is your preference).

Rehydration no longer fits into my “Short n Shoddy” brew day, so directly into the fermenter it goes! Case closed for me.

Thanks guys – for another great Xbmt – Cheers!

I noticed this exbeeriment did not oxygenate. Is the lack of oxygenation recipe- or yeast-specific ? A veteran homebrewer I know that uses Fermentis says the dry yeast has oxygen in it and he never oxygenates nor rehydrates. He has brewed a national champion beer. I found the following exbeerimeent on whether to oxygenate or not. https://brulosophy.com/2015/10/19/wort-aeration-pt-3-nothing-vs-pure-oxygen-exbeeriment-results/

There will always exist a degree of intrusion by unwanted organisms. Anything that gives the desired colony an advantage is a worthwhile investment of my time.

Couldn’t this go either way? By rehydrating you introduce a (admittedly small) chance of infection as opposed to direct pitching from a sterilised packet into a recently boiled wort?

Any advantage the brewer’s yeast is given by rehydration is also given to any unwanted organisms hitchhiking in or on the packet. So the advantage you hypothesize is probably cancelled out.

I’m often confused by either the motivation or the experimental design of what’s done on this site and, to be honest, the answers to my questions provide little addition illumination. What led you to not believe the initial result from Marshall? Wouldnt a higher gravity beer have given you a greater expectation of seeing a significant difference? (And it sounds like that would have given you a beer more to your tastes.)

Your pregnant wife is knocking back brews?!?

He said she could differentiate the samples based on aroma…

Even if she was there is most probably zero risk to drink a glass or two of beer late in pregnancy. It is during early development (first trimester) that the fetus is most sensitive to alcohol, and even then you probably would have to drink quite a lot and do it repeatedly to cause harm. In my understanding any effect of ethanol has only been seen in cases where the mothers were heavy drinkers, or correlated on a population level – where a significant finding is probably driven by those that drink most.

i think a lot depends on adding air to the wort and getting it into the right temp zone.

around 100-120 degrees, i rack from kettle to carboys. carboys go in the fermentation chamber and when they hit about 85, thats when i get to sprinkling the yeast.

things start fermenting within a few hours.

Nice to see another data set.

It would be interesting to better quantify the lag phase using a Tilt hydrometer. Both were “fermenting vigorously” at 24 hours, but it would still be interesting to see the curve.

Then there would need to be another xbmt comparing laggy beer to instant start since I’ve read some data that perhaps a longer lag phase is better for overall yeast health.

Alas, nothing matters anyway so I’m gonna rehydrate when I think about it and not be bothered if I forget. 😉

I switched a few batches ago to direct pitch vs rehydration based on the change in guidance by Fermentis. What I saw was a change to a more gradual ramp up of the fermentation and krausen with the direct pitch vs a more aggressive quick fermentation and krausen formation. I brew 1 gallon small batches and the direct pitch has lessened the need for blow off tubes the more and associated losses. If I remember the Fermentis research, the more gradual ramp up and slightly longer fermentation was what they noted and this actually gave healthier overall yeast than the aggressive fermentation of a rehydrates pitch.

Take a look at this clip. Very interesting in regards to dry yeast being put directly in wort. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=JInakA5L864

The old Fermentis instructions called for direct pitching at above 68F, and the new instructions show “Ideally, the yeast will be added during the first part of the filling of the vessel; in which case hydration can be done at wort temperature higher than fermentation temperature, the fermenter being then filled with wort at lower temperature to bring the entire wort temperature at fermentation temperature.” So they call for a warmer pitching temperature for dry yeast. What was the pitching temperature for this exbeeriment? And what was the yeast slurry temperature when pitched?

Once again, there’s real confusion about the concept of statistical significance and a misunderstanding that a non-significant result shows that the variable had no impact. In this case, since someone (the wife) was able to reliably distinguish the beers, the variable clearly had an impact. The non-significant result is clearly, without question, take it to the bank due to a small sample size. End of story.

Which renders the discussion hilarious. The author intends to continue to ignore the variable because the study — with a negligently small sample size — did not achieve a statistically significant result, despite recognizing that, in fact, people can demonstrably, reliably distinguish the beers!

LOL!

Respectfully, I think you’re the one that may be confused. What researchers want to know is, what’s the AVERAGE response in a sample? And then they use inferential statistics to extrapolate the sample response to a population as a whole. One person being able to reliably distinguish the beers is meaningless, if the population, on AVERAGE, cannot distinguish the beers. There will always be sampling units that land in the tails of a normal distribution, regardless of whether or not the independent variable had an effect. So the argument that “the variable clearly had an impact” because one person could distinguish the beers is nonsense.

So many commenters on these experiments bitch about “small” sample sizes. Because obviously Brulosophy is a billion-dollar company that employs thousands of trained elite sensory scientists. But personally, I’ll trust 25-ish experienced beer enthusiasts to be able to tell me if there’s a difference or not. Keep up the good work, folks.

Respectfully, this result actually shows that the AVERAGE tester COULD tell the difference. The p value was 0.14. It just didn’t reach a p value of 0.05 (which was the arbitrary cut off for statistical significance chosen, which would rule out false positives 19 times out of 20).

They’re not using statistics to extrapolate to the population as a whole, they’re using statistics to determine the likelihood that the result was due to chance. You shouldn’t weigh in if you have no idea what you’re talking about.

As far as your point about the inability to get a larger sample size — my issue isn’t that they get no -significant results due to small sample sizes. My issue is that they misreport non-significant results as though they show that the variable has not effect, which is wrong.

In this case there was actual data showing that the variable HAD an effect (the wife)!!!!

“Tasters couldn’t reliably distinguish the beers, but if you’re a pregnant woman who happens to be sensitive to aroma, you might be able to.”

I’m not sure that makes much sense.

It’s just homebrew dude. Take a deep breath. And for future reference, one exclamation point suffices.

Agreed, Marshall.

Freeheeler, okay I’ll take a breath. As a scienc-y homebrewer & a stats nerd, I can get worked up about this topic.

I’d like to see this replicated with a high gravity wert

I saw on reddit you are deleting/not allowing comments that are critical of your methodology… you have to know that whatever short term face you save by this, it just harms your credibility over time and moves the discussion elsewhere?

We don’t delete comments at all, never have never will. And with the exception of actual spam, we approve all comments. I’m curious where it is you saw this on Reddit.

I am not the one behind anything on Reddit about this, but I personally have submitted a couple of comments in the past that, after I clicked “Post Comment”, never appeared. Neither of these comments were in any way inappropriate, but yeah, they were constructive criticisms of the methodology or of a poster’s comment/reasoning. I have to admit, I assumed Brulosophy was censoring my comment. Nothing unusual happened on my end–meaning, no error message or weird browser behavior–so perhaps a software glitch?

To stop spam comments, we have to approve comments from all first time posters. Sometimes we miss them, though we usually get to them within a few days max. If we missed one of yours, I apologize and promise it wasn’t censoring!

Something similar happed to me a few months back once or twice, but nothing like that recently, and I’m often critical (with the spirit of constructive improvement, I hope)

Your wife has “pregnancy nose.” Mine could detect when I ate something with garlic, drank a barrel aged beer, snuck some of our kid’s fruit snacks, heck, even when I used my “back up” deodorant. Congrats to you and your lady!

TRUTH… mine knew a wildfire was coming to the neighborhood and had us get packed up and ready before evacuation was even a glint in anyone’s eye. She could smell it coming when no one had any thought it would be hitting our ‘hood. Sample size= 1, but yeah “pregnancy nose” def. a thing 🙂

Not everything is about if participants can tell the beers apart. The fact that you have seen fewer krausen on non-rehydrated batch at the beginnig or in other words that the lag phase was longer is a clear evidence that cells were affected/in worse shape than when properly rehydrated. If you care about the yeast, and you should, just this is enough for me to rehydrate them. Happier yeast is always a good thing. When everything else is ok there is no wonder that the beers taste the same at the end but having shorter lag time is always desirable because before the yeast really kicks in the beer is most vulnerable to potential contamination. On this particular recipe, the small difference in vitality of the yeast may not make a difference but once you put more strain on the yeast (such as brewing strong beer) it can be completely different story. It works, yes, but there is no doubt that it is not optimal. Why would I do something that is not optimal if the better alternative is so simple? To save a little bit of work? Not for me 🙂 I actually brew because I like the labor involved (often even more that drinking the beer) and I enjoy giving my yeast the best treatment that I can. The promise of good-tasting beer should not be all that we care about. I see this as a shortcoming of all exBeeriments – you often discuss what literature suggests but you kind of completely ignore that best practices are not only about the taste of the beer at the end but also about optimization of the procedures in order to establish robust techniques minimizing chances of negative outcomes.

While I admire the methodology, I’m disappointed in this one. An experiment is only as good as it’s design… and this one is really confusing. You rehydrate yeast to help it get a leg up, due to either (1.) yeast’s condition (2.) the state of the wort it will be facing (3.) insurance against other organisms that want to feed on the sugars.

Your test didn’t look at any of these things, and since 2 weeks is a full ferment for many styles, including what you chose, and you spent a lot of time reaffirming that you will have a faster ferment with rehydrated yeast and none of the rest really mattere.

It’s known that tossing a packet of yeast in dry will kill a bunch of cells, basically due to environmental shock as the yeasts try hydrate in liquid filled with sugars. However with modern packaging you are talking billions of cells, and losing some will still leave more than enough to deal with a normal ABV and wort conditions. It’s why many manufacturers are now saying to just toss it in unless you have adverse conditions, which you have to be aware of.

Your time and content are your own, but I’d suggest what would have been more helpful — and useful to the readers/community — would be the same experiment while making the wort environment or yeast condition more challenging.

People used to get really, really old yeast — that had smaller initial cell counts — in stuff like can kits and other places and old stock. Rehydrating became the norm because you could greatly reduce the chance of stalled fermentations, and even know if it was viable at all. Even now, your packet could have been left in the sun during shipping. You could replicate old, depleted-count yeast in a variety of ways (eg., take 0.25 of an expired dry yeast packet, then divid again with one half given a starter and the rest tossed in dry).

Alternately, you could have made the wort environment more challenging, which is a *far* more likely scenario to any brewer. e.g., you could have done a very high ABV beer, so the yeast was dropped into a high-sugar environment where starters are recommended. You could have fermented out of the yeast’s ideal temperature range. You could also test it’s ability to outcompete other organisms, like wild yeast/etc., via perhaps an open ferment. Or, the same experiment, yet shorten fermentation time to 5-7 days.

You can use sound methodology to test anything, but you have to ask what you’ll really learn by the effort and if it’s adding real value to what’s known. In this case, we learned your rehydrated starter was able to be up and running quicker, but the parameters made none of the rest matter. And what was learned was already well-known, with the science behind it well-established.

Again, your time is your own, but I’m hoping you take the next step!

I agree that this experiment added nothing worthwhile, unfortunately. Fermentis is an actual company that produces an honest to goodness product (rather than ad revenues or Google hits) and has trained specialists on staff to run laboratory trials to determine whether rehydration is needed. Google searches quickly turn up results of these trials: https://www.winesandvines.com/news/article/201266/Skipping-Hydration-for-Wine-Fermentation. Granted, that link is for wine yeast, but applying some Google-Fu might turn beer-centric results up pretty quickly.

In any case, as someone doing this as a hobby, I want to be sure that I am getting my money’s worth and that I’m not wasting my time, like paying for liquid yeast that I have to make a starter of when I could pay less for a pack of dry yeast that I directly pitch. That being said, Fermentis has run more trials in more ways and published more data about this than will ever be done here about pitching yeast directly into wort. That being the case, embrace the spirit of homebrewing and push the envelope for once. Try an experiment where the variable could cause the beer to fail entirely. The short and shoddy series is approaching this, but it is still lacking; what mashing for just a few minutes, leaving the grains in the boil, or fermenting in milk bottles with only the lid screwed partially on? Direct pitching dry yeast into 1.051 wort with ideal fermentation conditoons is not worth a write-up, in my opinion.

I think wort gravity is an important variable. Osmotic pressure will increase with gravity and should affect badly viability. Two options then, more yeast or réhydratation!

Since Lallemand indicates within their various brewing yeast technical data sheets that no aeration is required for any of their dry yeasts, an interesting exbeeriment would be to adequately aerate one fermentation and apply no level of aeration to another.

Like this series from 2015?

https://brulosophy.com/2015/05/25/wort-aeration-pt-1-shaken-vs-nothing-exbeeriment-results/

https://brulosophy.com/2015/07/13/wort-aeration-pt-2-shaken-vs-pure-oxygen-exbeeriment-results/

https://brulosophy.com/2015/10/19/wort-aeration-pt-3-nothing-vs-pure-oxygen-exbeeriment-results/

I might just be missing something here, I thought that the purpose of this exBEERiment was to (re)test whether or not rehydrating dry yeast would impact the flavor of the beer under this tester’s normal (common practice) conditions. It seems that the possible impact rehydration would have on high gravity wort, or pitching at a higher/lower temperature would be the subject of different exEERiment entirely. Personally, I am glad to see someone recreate a past test to evaluate whether or not it has a significant impact on their process and can then make an informed decision to follow “best practice” or not based on their own findings.

Shouldn’t have used Nottingham as the sample yeast. We all know that one is a beast of a yeast. I get the headspace full of krausen and the carboy rockin in less than 24 hours every time I use it. Dry pitched.

now do the experiment with starting gravity above 1.060

Thank you very much for doing this repeat xBmt as well as all the others. I really appreciate all the time and effort you guys put into this. From design to pulling it all together, it’s really a lot of work. I’ve been brewing a long time, first using can of malt syrup and some kind of hops and dry yeast. Things sure have improved, particularly dry yeast. While like many, I mostly use liquid yeast, I still use dry for certain brews and I always struggle with re-hydrate vs direct pitch. For the beers that I use dry yeast for, I’ll stick with direct pitch.