Author: Marshall Schott

According to some accounts, English maltsters developed the process for making Crystal malt sometime around the turn of the 19th century. Unlike standard base malts, Crystal malt is left wet after germination and allowed to sit at saccharification temperatures for a few hours before being roasted to varying degrees of color. Originally intended as a means to add depth of flavor to ever weakening British beers, Crystal malt usage grew rapidly and soon became a staple in English breweries for its ability to contribute toasty, toffee, and biscuit-like character to beer.

As maltsters began taking root across the pond, new versions of this malt began to hit the market, which due to proximity, provided American brewers a more affordable option. Caramel malt, as it’s called some in the US, is purportedly made using a similar process to produce a product that rivals the quality of English Crystal malt. While Caramel and Crystal are used interchangeably these days, I feel it’s prudent to clarify that Briess, one of the largest US manufacturers of Caramel malt, says they are in fact different, explaining, “Caramel malt is applied to both kiln and roaster produced caramel malts, but the term crystal malt is normally reserved for caramel malts produced in a roaster.”

As is often the case when multiple options of a similar product are available, opinions and preferences regarding Crystal malt are held by many. I’ve heard from some brewers who swear that UK Crystal malts impart a more robust and authentic character to their beer, while domestic varieties are generally lacking in depth and contribute a more sugary sweet or even somewhat tart component. Of course there are also those who view such regional differences as minutiae, relying on whatever is available or cheapest.

Confession: prior to this xBmt, I’d never knowingly used UK Crystal malt, not once in the 13 years I’ve been brewing. Because of this, I never developed an opinion either way on the matter, though recent comments I’d heard claiming that authentic English styles demand the use of UK Crystal malt made be wonder – is it really all that different?

| PURPOSE |

To investigate the differences between UK and US Crystal malts when used in beers of otherwise similar recipes.

| METHODS |

When considering a recipe for this xBmt, I knew I wanted to keep it very simple in order for any differences between the batches to be noticeable, so I opted for what I might call an old school Pale Ale with a grain bill of just pale 2-row and crystal malt. The UK and US Crystal malts used in this xBmt were from Bairds and Briess, respectively.

Crystal Pale Ale

Recipe Details

| Batch Size | Boil Time | IBU | SRM | Est. OG | Est. FG | ABV |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5.5 gal | 60 min | 43.5 IBUs | 8.8 SRM | 1.053 | 1.011 | 5.6 % |

| Actuals | 1.053 | 1.009 | 5.8 % | |||

Fermentables

| Name | Amount | % |

|---|---|---|

| Pale Malt, 2 row (Gambrinus) | 10 lbs | 90.91 |

| UK Crystal Medium OR US Caramel 60L | 1 lbs | 9.09 |

Hops

| Name | Amount | Time | Use | Form | Alpha % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Magnum | 14 g | 60 min | Boil | Pellet | 11.2 |

| Mt. Hood | 21 g | 25 min | Boil | Pellet | 5 |

| Citra | 28 g | 10 min | Boil | Pellet | 13.4 |

Miscs

| Name | Amount | Time | Use | Type |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Calcium Chloride | 5.00 g | 60 min | Mash | Water Agent |

| Gypsum (Calcium Sulfate) | 5.00 g | 60 min | Mash | Water Agent |

| Lactic Acid | 4.00 ml | 60 min | Mash | Water Agent |

Yeast

| Name | Lab | Attenuation | Temperature |

|---|---|---|---|

| Safale American (US-05) | DCL/Fermentis | 77% | 59°F - 75°F |

Notes

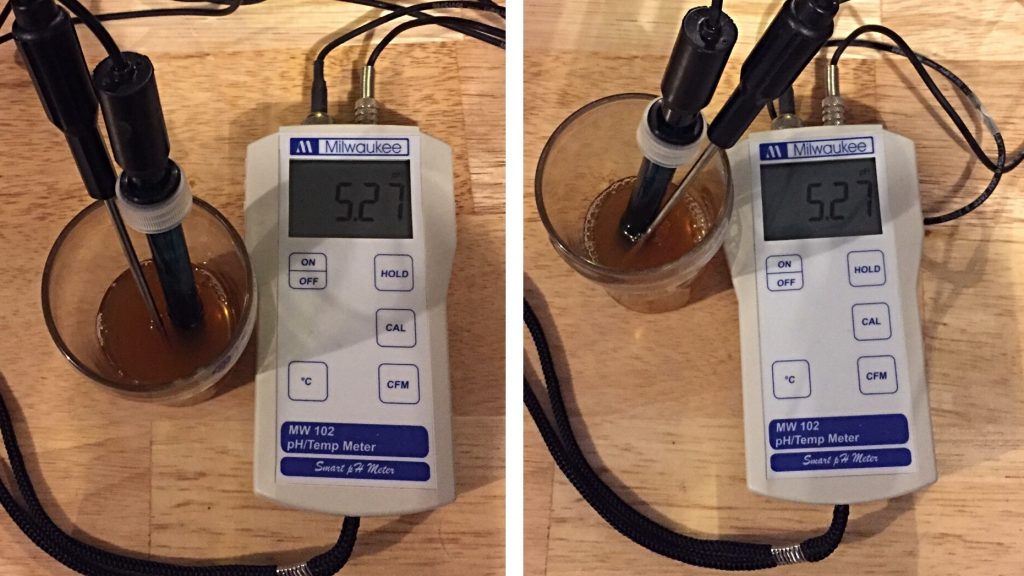

| Water Profile: Ca 79 | Mg 1 | Na 10 | SO4 89 | Cl 73 | pH 5.27 |

Download

| Download this recipe's BeerXML file |

I used Safale US-05 American Ale for this xBmt because it’s clean and I was too busy partying over Thanksgiving weekend to make a starter, which is also why I didn’t prepare things the night before brewing like I usually do. I started by collecting the full volume of strike water for each batch, as I used the no sparge method, then adjusting each to the same target profile with minerals and acid. I hit the flame under what would become the UK Crystal batch 20 minutes before the second batch to make the brew day more manageable.

While the water was coming to temperature, I weighed out the grains and took note of any differences between the UK and US Crystal malts. They looked pretty damn similar to me.

Each set of grains was milled into its own marked bucket.

Once each batch of water was heated to a few degrees above the strike temperature recommended by BeerSmith, it was transferred to a MLT for a brief period of preheating before I added the grist, both batches settling at the same mash temp.

Each mash was left to rest for 60 minutes with brief stirs every 15 minutes.

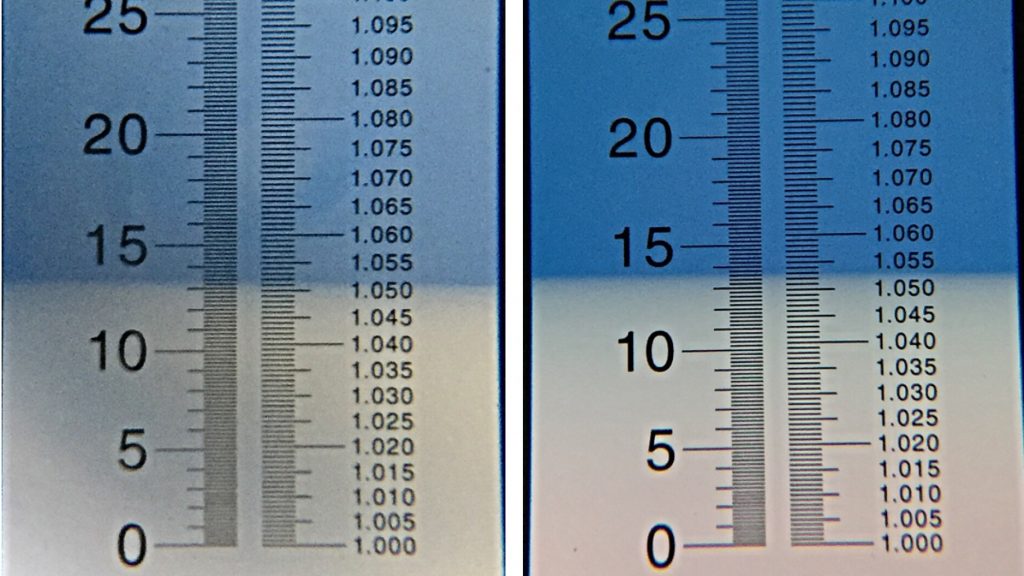

At 10 minutes into either mash, I pulled samples for color comparison and pH measurement.

Although they shared the same color and pH, in tasting them, I felt the US Crystal wort had a slightly more tart character to it, albeit I sampled them 20 apart from each other. At the conclusion of each hour long mash, the full volume of wort was collected, transferred to a kettle, and boiled for an hour.

Once the boils were finished, I hastily chilled the wort to a bit above my annoyingly warm groundwater temperature of 72°F/22°C.

A refractometer measurement at this point revealed a slight OG difference between the worts that I’m doubtful had to do with the variable.

I transferred 6 gallons of each wort to separate fermentors that were placed next to each other in the same cool chamber to finish chilling to my desired fermentation temperature.

Before cleaning my kettles, I collected two 500 mL sets of leftover wort in sanitized flasks and sprinkled 1 pack of Safale US-05 into each for vitality starters.

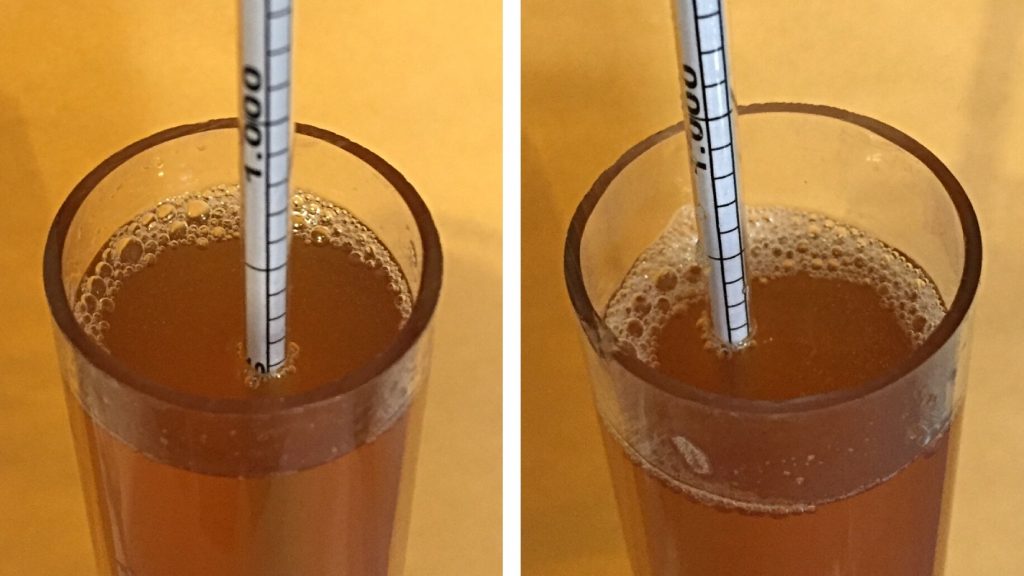

Both worts had stabilized at 66°F/19°C 4 hours later so I pitched a starter into each. Unlike my experience pitching rehydrated or sprinking on dry yeast, I noticed airlock activity less than 4 hours after pitching. The beers fermented for 5 days before I ramped the temperature up to 72°F/22°C to encourage complete attenuation and clean-up of any fermentation byproducts. I left the beers at this warmer temperature for another 5 days before taking hydrometer measurements showing FG had been reached for both.

The beers were cold crashed, fined with gelatin, and kegged 2 weeks after being brewed.

I placed the filled kegs in my keezer and burst carbonated them overnight before reducing to serving pressure. When it came time to collect data the following weekend, both were brilliantly clear, nicely carbonated, and seemingly the same color.

| RESULTS |

In total, 22 people of varying experience levels participated in this exBEERiment. Each taster was blindly served 1 sample of the UK Crystal beer and 2 samples of the US Crystal beer in different colored opaque cups then asked to select the unique beer. At this sample size, at least 11 accurate selections (p<0.05) would be required to achieve statistical significance, though only 9 (p=0.29) accurate selections were made. These results indicate tasters in this xBmt were were unable to reliably able to distinguish a beer made with medium UK Crystal malt from a beer with the same amount of 60°L US Crystal malt.

Despite failing to achieve significance, I thought it’d be interested to share the preference data gathered from only those who were correct on the initial triangle test. Still blind to the variable and comparing only the two different beers, 5 tasters said they preferred the UK Crystal beer, 2 liked the US Crystal beer better, and 2 felt there was no difference.

My Impressions: During a data collection session in my garage, I asked a participant who had completed the survey to pour me samples for a triangle, keeping my eyes closed while she handed me each cup. I was right! Of course, I went on about how I was able to tell them apart and what I perceived as being different. Then a few days later, I did two more triangle tests served by my neighbor Tim. Confident in my ability, I swiftly selected the beer I knew was unique… and I was wrong. Tim mixed them up and served me again, this time I got it correct, my first attempt an obvious fluke. Finally, during a recent video chat with our Patreon supporters and the other contributors, I performed 4 more blind triangles, each time failing to select the unique sample. It was at this point I accepted the beers were far too similar in every respect for me to reliably tell them apart.

| DISCUSSION |

With all I’ve heard about how much better UK Crystal malt is than its US equivalent combined with the significant results from our xBmt comparing Maris Otter to US Pale malt, I was pretty well convinced these beers would be easy to distinguish and even expected to prefer the uniquely English character of the UK Crystal malt beer. At the same time, I didn’t find it terribly surprising participants and I were unable to reliably distinguish the beers, partially due to the fact I’d never used UK Crystal malt and hadn’t formed strong opinions on the matter. Furthermore, as important as proprietariness may be, I can’t help but wonder if the process variations between maltsters simply aren’t vast enough to create a huge qualitative difference in the finished product.

One limitation to this xBmt is that we used malts from only two maltsters, perhaps other brands of UK Crystal malt would have produced a different outcome. Similarly, we used only one of a plethora of different colors of Crystal malt, leaving me curious if lighter or darker Crystal malts from either region might be more disparate. Finally, it’s possible either malt might have presented differently if used at different rates.

In the end, I plan to stick with the less expensive and readily available US Crystal malts, though I’m far from believing those who choose otherwise are doing so pointlessly and I look forward to continued exploration of regional ingredient differences.

If you have thoughts about this xBmt, please share them in the comments section below!

Support Brülosophy In Style!

All designs are available in various colors and sizes on Amazon!

Follow Brülosophy on:

FACEBOOK | TWITTER | INSTAGRAM

If you enjoy this stuff and feel compelled to support Brulosophy.com, please check out the Support Us page for details on how you can very easily do so. Thanks!

26 thoughts on “exBEERiment | Grain Comparison: UK Crystal vs. US Caramel Malt In An American Pale Ale”

Considering the relative cost difference per batch of beer I would say use whatever malt you like. More importantly insure it is fresh. In humid parts of the US malt in an HB shop can get mealy fast and stale. It would be best to vacuum seal special malts or buy on demand only. The one HB supplier that provides sealed malt is Northern Brewer. When I buy local I try to make sure I store in zip lock bags inside an old 55lbs grain bag that is resistant to oxygen diffusion

Where can I get those cool tasting glasses?

Still trying to figure out a good way to sell them that wouldn’t cost people more in shipping/packaging than the actual glass costs.

You could bring a case of them to NHC or other big conferences (PNWHC is coming up fast) – Divide that $50 checked bag fee up between the glasses you sell.

Only if it was cost effective to send to Australia then I’d throw out my other glasses for these bad boys!

Interesting variable to test. Ive used US, German, and U.K. Crystal/ caramel malts while following recipes before. They each certainly taste different, and in ways that appear to be somewhat consistent by place of origin.

While this test was good to test any detectable difference in a common beer one might brew, where I have seen maltser and country of origin stressed is definitely in more malt forward and traditional regional styles. I would be very interested to see this same variable tested in a Scottish ale or English bitter or mild. The 40+ IBU and hop character could be masking the subtle characteristics of the 1 lb of character malt.

This is right on. If we are going to examine malt character, choose a style that highlights malt.

Further, I wonder about flavor stability over time with these malts. I had heard Vinny from RR on a BN interview several years ago state that as US crystal has a bad interaction with American hops as they fade out of the beer and the beer oxidizes.

We were examining Crystal malt character and brewed a beer that wouldn’t ostensibly hide that.

I’ve been part of a quality team at several Socal breweries and conducted several aging studies. Have never found any oxidation issues with major beer brands which use Crystal malts.

Wouldn’t a Brown Ale or something with lower IBUs have been a better choice to showcase the malt flavor rather than covering it up with the higher IBU numbers in an APA? Then testers could have better tasted the flavor of the malt rather than the hops.

These beers were not bitter or hoppy at all. The roasted malt in a brown would have ostensibly covered up the crystal malt character as well.

Perhaps I should have just called it an ESB…

That may be your personal opinion – but going over 40 IBU makes it more bitter than 95% of beer in British pubs, and lets face it Citra doesn’t exactly hide its taste under a bushel. If your intro is talking about “a staple in English breweries” and “authentic English styles”, then a test beer that reflects British styles might be appropriate – and to be honest I can’t think of a style that shows off crystal better than a Best Bitter, something like Pedigree or Harveys or Belhaven 80/-.

Given that the test was only 2 people away from significance, I suspect the extra bitterness and terpenes probably made the difference.

Oh, and ESB exists far more as a style in the imagination of the BJCP than in the reality of British pubs….

You’re going to get hate mail from the other side of the Atlantic for this one 🙂

I don’t think British brewers are that precious about crystal malt. Home brewers do rave about maris otter, and some brewers about the extra low colour maris otter. And the terroir of the hops (e.g., UK Goldings vs US Goldings). Other than that it’s mainly US brewers who want to use UK products. In the UK, however, it’s nearly impossible to get US malts (for example, I’ve never found US 2 row or any Briess malt).

Morebeer ‘s malt is vacuum sealed all also

Man, funny you did this cause I recently ordered a bunch of UK Crystal malt (simpsons) and really love it. Side by side compared to briess Crystal they even look completely differnt. The taste is definitely differnt when I just eat the grain, but who knows once you get it in a beer. Awesome test! Thanks for the effort!

I have always used Muntons Crystal 150 ( 130-170 EBC or 56-70 L ). I haven’t been able to get it lately and I do notice quite a difference versus a 60L malt.

Which malters were used for the various malts? How were they selected?

Baird’s and Briess, both from MoreBeer.

What palate cleansing measures are the tasters employing? Same for all xBmts?

Every taster is offered water, occasionally crackers, though many don’t use them. In fact, in my own trials, I’ve found I prefer not to “cleanse my palate” between samples, as I like to go through them quickly enough to hopefully catch any differences with lower chances of forgetting.

Bairds MO is often seen as a pretty cheap and not the greatest, there are a lot of threads on the UK boards with people complaining its extraction etc . I not sure what their crystal is like but you might want to try Thomas Fawcett or Crisp if you have access to it.

When you say, “The beers were cold crashed, fined with gelatin, and kegged 2 weeks after being brewed.” I have fined with gelatin.. I get that part. I understand what cold crashing means (and since it’s winter in Western PA, I can do that via mother nature, since no $ for temp controllers or extra keezers). What I don’t know is time… Do you cold crash 2-3 days then fine with gelatin, leaving the gelatinized beer in the cold crashed state for 2-3 days… What are the steps in the process, for you? How long for each step?

Cold crash for ~12 hours, I usually go overnight, add gelatin and let sit for another 12-48 hours before kegging. I’ve come to believe the timing isn’t all that big of an issue. A couple of the contributors do their gelatin fining in the keg, which I’ve done as well with similar results.

You wrote “The beers fermented for 5 days before I ramped the temperature up to 72°F/22°C to encourage complete attenuation and clean-up of any fermentation byproducts.”. From reading a thread on british brewing, they recommend quick ferments and then get the beer off the yeast. I have been able to complete fermentation in 2-3 days with a healthy yeast. You have conical fermenters which allows you to easily monitor the FG. You should be able to measure the FG until it gets to the desired value, then transfer to the keg. That way the beer doesn’t get stripped of too much residual sugars and any yeast introduced flavors. Maybe you have already done an experiment like this and I haven’t seen it in the long list…

Very good work you are doing to find out whether various products do what they say they do….and generally don’t! Have you tested out wheat additives, such as torrified wheat and wheat malt to see if these help with head retention? Everybody claims they have an effect but advise keeping the amount low if you want a clear beer without protein haze. I’ve never had much luck with them. In fact the only product that has made a huge difference to me is a product known as “Heading Compound” in the UK. It’s a very fine cream colored powder which lists maltodextrins and “yeast elements” as the only ingredients. It work fantastically well for me if a very small amount is sprinkled onto the surface of the beer once poured out, and agitated gently at the surface with something like a chopstick. It produces a long lasting head every time, that laces well and lasts all the way down the glass, giving a soft smoothness to the flavor. I use it all the time now. I used to add it to the beer before bottling and priming but it was a lot less effective. https://www.biggerjugs.co.uk/products/beer-heading-compound-100g-pack-use-to-ensure-a-long-lasting-head-on-home-brewed-beers-lagers

A liquid heading product I bought had no effect at all, which contained propylene glycol alginate. It was completely useless.