Author: Ray Found

In all grain brewing, the importance of mash temperature is discussed ad infinitum, though it’s little sibling, responsible for finishing up the job of the mash, is largely neglected. The sparge is an integral part of the lautering process that involves rinsing the grain of residual sugar once the mash is complete. While some newer homebrew methods forgo this process, such as Brew In A Bag, many continue to sparge in order to achieve intended levels of sugar extraction, aiming for the commonly accepted grainbed temperature of approximately 170°F/77°C said to halt enzymatic activity and improve lautering by reducing wort viscosity. Indeed, conversations about sparge temperature tend to focus mostly on the negative effects of sparging too warm, namely the extraction of astringency causing tannins, yet relatively little exists about the impact of sparging with cool water.

Back in 2009, Kai Troester published an article on his cold-sparge experiment where he found sparge water temperature to have no apparent impact on overall efficiency or fermentability. Inspired by these findings, American Sour Beers author and blogger at The Mad Fermentationist, Michael Tonsmeire integrated the use of cool water in what he refers to as his “Minimal Sparge Process,” which he has reported satisfactory results with.

My interest in this topic stems largely from comments regarding the recent xBmt comparing the batch sparge method to fly sparge. A few brazen, rule-bucking brewers informed me they started sparging with unheated water in order to ease and streamline their brewing process, reporting no noticeable negative effects. As skeptical as I am, their rationale seemed sound– the enzymes had already done what they needed to do during the mash, conversion was complete, and there’s no good evidence suggesting 170°F/77°C dissolves and rinses sugar substantially better than room temperature water.

I’ve personally never paid much attention to the temperature of my sparge water and have always been most concerned with keeping it below 180°F/82°C in order to avoid the dreaded extraction of tannin. I’d never even considered sparging with unheated water, until now, that is.

| PURPOSE |

To evaluate the differences between two beers of the same recipe where one was sparged with cool water and the other standard sparge temperature water.

| METHODS |

I love American Amber Ale and it was time to get one on tap, so I designed a new recipe I thought would produce what is I appreciate most about the style.

Make America Amber Again

Recipe Details

| Batch Size | Boil Time | IBU | SRM | Est. OG | Est. FG | ABV |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5.5 gal | 60 min | 78.8 IBUs | 15.7 SRM | 1.053 | 1.007 | 6.1 % |

| Actuals | 1.053 | 1.01 | 5.6 % | |||

Fermentables

| Name | Amount | % |

|---|---|---|

| ESB Pale Malt (Gambrinus) | 8.124 lbs | 65 |

| Munich Light 10L (Gambrinus) | 2.5 lbs | 20 |

| Caramel/Crystal Malt - 40L | 1 lbs | 8 |

| Caramel/Crystal Malt - 20L | 8 oz | 4 |

| Pale Chocolate Malt | 6 oz | 3 |

Hops

| Name | Amount | Time | Use | Form | Alpha % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Magnum | 10 g | 60 min | Boil | Pellet | 12.1 |

| Cascade | 60 g | 15 min | Boil | Pellet | 9.3 |

| Amarillo | 40 g | 15 min | Boil | Pellet | 7.7 |

| Centennial | 20 g | 15 min | Boil | Pellet | 11.1 |

Yeast

| Name | Lab | Attenuation | Temperature |

|---|---|---|---|

| San Diego Super Yeast (WLP090) | White Labs | 80% | 65°F - 68°F |

Download

| Download this recipe's BeerXML file |

After dosing my water with calculated amounts of CaCl- and gypsum, I set to the task of measuring out and milling two identical batches of grain.

I staggered the start of each batch by about 15 minutes to make things less complicated, but the process for each was exactly the same. It’s because of this precision my failure to hit my target 149°F/65°C mash temperature was consistent between the batches.

During the mash rest, I prepared the sparge water, a very simple task for the cold sparge batch that involved measuring it out in a graduated bucket and adding the required minerals. The standard sparge batch would prove only slightly more difficult, requiring a few minutes on my powerful burner. My groundwater was running at a balmy 75°F/24°C on this day and I heated the standard sparge water to 172°F/78°C for a difference of 97°F/54°C!

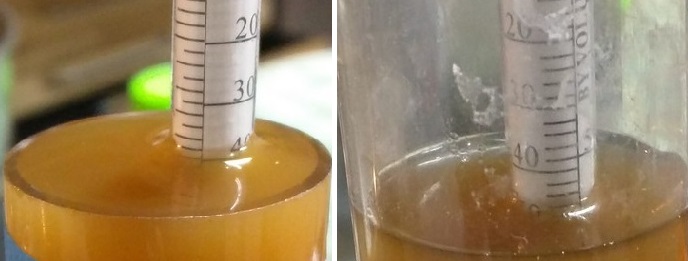

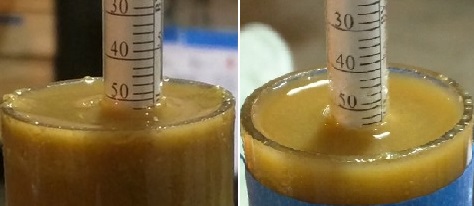

For both batches, I performed a brief vorlauf at the conclusion of the mash then collected the first runnings before adding the sparge water per my usual batch sparge routine. I measured temperatures at this point and found the standard temperature grainbed to be just over 155°F/68°C, while the cold water had dropped that grainbed to 93°F/34°C.

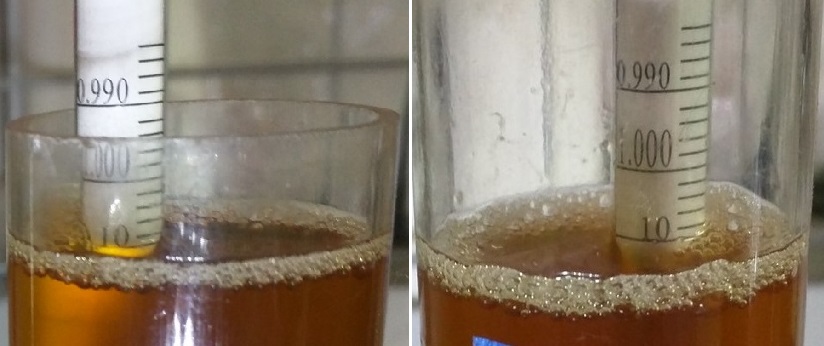

For whatever reason, I ended up with a little more wort from the cool sparge batch, less than a quart altogether, and I’m not certain why. It’s possible this difference in volume explains the discrepancy in pre-boil hydrometer measurements, which revealed the cold sparge batch to be slightly lower than the the hot sparge wort.

An often overlooked aspect of an xBmt brew day, I used the time during the boil to do some clean up, returning gadgets to their spots in my cart and giving my mash tuns a good wipe down.

After both batches completed their 1 hour boils, I quickly chilled the worts and again notice a small difference in volume. Hydrometer measurements at this point showed the SG gap had closed a bit, and volumes in the kettle had equalized.

Separate 6 gallon PET carboys were filled with equal amounts of wort from either batch and placed in my chamber to finish chilling to my target fermentation temperature. Having been travelling for work the day prior to brewing, I was unable to make a yeast starter and opted to use Safale US-05. I knew I didn’t have any at home, so I stopped into a great shop in Spokane, WA called Jim’s Home Brew on my way to the airport and bought 4 packs.

Once the worts reached the proper temperature, I pitched a rehydrated pack of yeast into each then it was off to another week long work trip. Hydrometer measurments taken when I returned 11 days later showed both beers had dropped to the same 1.010 FG.

I proceeded to cold crash and fine with gelatin. Five days later, it was time to keg.

After only 20 hours at 40 psi in my cool keezer, the beers we nicely carbonated, almost perfectly clear, and quite tasty!

| RESULTS |

All in all, 17 people participated in this xBmt including beer loving friends, homebrewers, and a couple podcast hosts. Each taster was blindly served 2 samples of the standard sparge beer and 1 sample of the cool sparge beer then asked to select the unique sample. In order to reach statistical significance with this sample size, at least 10 participants (p<0.05) would have had to made the accurate selection, yet only 7 (p=0.33) were able to do so. While we don’t usually report individual performances, I’ve been given permission to share that the pool of correct tasters did not include any podcast hosts. These results demonstrate participants in this xBmt were unable to reliably distinguish a beer produced using standard temperature sparge water from one sparged with cool water.

My Impressions: Both batches tasted absolutely the same to me, I can’t identify anything about them that is different, despite a 0.002 OG and 0.26% ABV difference. Whether comparing blind or not, no way no how– these beers were identical to my unimpressive taste buds. And frankly, it’s a great beer for my tastes! I perceive a nice dry, toasty character, not overly caramelly, and noticeably hoppy without being particularly bitter. An easy drinking pint with a gorgeous color that I’ll surely make again.

| DISCUSSION |

The results from this xBmt support the notion cold sparging produces a beer perceptibly no different than sparging with standard temperature water, meaning either can likely be used with little risk of detriment. This being the case, some may be wondering whether or not they should change their method, which I believe is a perfect opportunity for a simple cost-benefit analysis. From a thermodynamics perspective, it’s true that sparging with cool water does actually conserve a slight amount of energy compared to sparging with warmer water. However, the tradeoff is time, as the cool sparge method leads to an ultimately cooler volume of wort in the kettle, which takes longer to bring to a boil.

One potential benefit of sparging with cool water is the reduced risk of tannin extraction, an issue often associated with sparging with water that’s too hot, something I’m personally skeptical even matters. Perhaps the greatest benefit is something Michael Tonsmeire noted in his aforementioned article, that the cool water reduces the temperature of the grainbed thereby making it easier to clean out one’s mash tun.

Additional trials are required to know with any certainty, though I’m inclined to think the OG difference between each batch, minor as it may have been, was a real effect of the variable. Since the cool sparge beer had a lower OG than the standard sparge batch, those concerned with efficiency might want to stick the standard approach.

As for me, I won’t be changing my routine, as it didn’t make my life any easier and actually added more time to my brew day. It’s possible cool sparging may be of use to some brewers, particularly those blessed with perfect brewing water out of the tap, or dunk-sparge BIAB’rs who might not have an easy means of heating additional water. Regardless, the results of this xBmt upheld the point of those who mentioned the method to me — cool sparging was not detrimental to the final product.

What kind of sparger are you? Do you target a specific sparge temperature or do you rinse your grain willy-nilly? Please share your thoughts and experiences in the comments section below!

Support Brülosophy In Style!

All designs are available in various colors and sizes on Amazon!

Follow Brülosophy on:

FACEBOOK | TWITTER | INSTAGRAM

| Read More |

18 Ideas to Help Simplify Your Brew Day

7 Considerations for Making Better Homebrew

List of completed exBEERiments

How-to: Harvest yeast from starters

How-to: Make a lager in less than a month

| Good Deals |

Brand New 5 gallon ball lock kegs discounted to $75 at Adventures in Homebrewing

ThermoWorks Super-Fast Pocket Thermometer On Sale for $19 – $10 discount

Sale and Clearance Items at MoreBeer.com

If you enjoy this stuff and feel compelled to support Brulosophy.com, please check out the Support Us page for details on how you can very easily do so. Thanks!

54 thoughts on “exBEERiment | Impact Sparging With Cool Water Has On An American Amber Ale”

Another great and relevant experiment. I (once again) used to kinda worry whether my sparge bed would reach that all-important 170 degrees, but once again you all have shown that it is not something I need to fret over. Once again, close is good enough. A possible experiment would be the opposite: what if you brought your grain bed up to 200 degrees. Would you get the dreaded tannin extraction?

You’re wrinkling my brain over here. I sorta cool-sparged one time when I accidentally ran short of sparge water and just made up the difference with my hose, but that was maybe a gallon or two. I’ve never even thought of foregoing 170 degree water. I’ll need to mull this one over to determine if I’m going to change my process. Like you said: it takes a lot less time to heat 140-150 degree water to boiling than 90-100 degree water, and I heat up my sparge water during the mash, so I don’t think I’d be saving any time.

Anybody knows the owner of this blog?

That would be me. What’s up?

I’ve always heated sparge water to 180 or so to bring the grain bed temp to the mid-160’s. Hell, I’ve even sparged with water at 190 or more when my mash temp fell more than expected. Are most of you aiming for the sparge water to be around 170, or the grain bed?

Grain bed.

If I recall correctly, you made an exBeeriment where you put a great deal of grain into the kettle and didn’t notice any astringent mouthfeel. So I guess, there won’t be much of a difference between doing this and sparging with boiling water in terms of tannins extraction. What do you think?

Great xBmt! As for the difference in volume, it’s simply that hot liquid takes more volume that cold; I was expecting that you’d adjust for that, but it did not seem to influence anything really! Cheers!

But the Exbeerimenter said that “I ended up with a little more wort from the cool sparge batch” (emphasis mine). I would think he’d have ended up with more wort from the hot sparge batch since, like you say, the warmer water should have a greater volume, no?

Ray, did you measure x gallons of cold water and x gallons of hot water or x gallons of cold water and x gallons of cold-to-be-heated water? If the former, the hot water batch will have a higher OG and lower final volume. If the latter, they should be equal volume

Yeah, I think I just let it dribble out longer on the cold sparged beer. Volumes were equalized by the end of the boil, but a small gravity difference remained.

@aaron – All water was measured cold.

As always, I love the idea that people isolate a variable and see what difference there is. Here’s one minor argument in favor of heating sparge water: what comes out is warmer, ergo, getting to a boil is faster. Yeah, it’s all I’ve got. 🙂

This is one of the relatively fewer XBMT’s that have an objective measure of the dependent variable, i.e., gravity. In this case warm sparge water appears to have rinsed more sugars, so efficiency is slightly higher.

I don’t think that more sugars were rinsed out. Based on Kai’s original work, what probably happened was that the mash conversion was not complete, and raising the grain bed temp to 155 finished the job.

Possible – for the sake of clarity, I should mention the final temperature of the grain bed was AFTER LAUTER, it reached 163.4F when it was full of sparge water. By the time it was done draining, it had dropped to 155F residual grainbed temp.

Sparge water mineral additions also dissolve better in heated water.

The lower pre-boil gravity could be due to the fact that cool water is not lowering the viscosity of the wort, so the sugars are remaining in the grains rather than washing out.

Great job Ray – makes me want to run an extreme test with 168F vs. 190F water and see if those tannins happen.

Tannins are created at mash temps – EXCESS tannins are created when pH rises above 5.8 at mash temp, so the increase in temp at the correct pH should have little impact on excess tannins.

How does one determine which tannins are excessive?

Very nice post! My mashing process usually involves the standard temperatures but as one other person mentioned I did run short on sparge water in one instance and used straight tap water and I didn’t notice anything off about the final product. As you concluded I don’t think I’ll change my mashing process but it is an interesting concept. Thanks for all the time you put into these xBmt’s!!!

I’ve been interested in this for a while now so thanks for the write up!

I brew on a HERMS system and I perform a mash out, not that I think a mash out will help my beer, it’s simply a step to get to sparge temp. After the mash is done I keep recirculating and raise the HLT temp to about 170, drain the wort from the mash tun and batch sparge. I don’t think the cold sparge method would help with my setup at all, even with a slightly more significant result.

I wonder how much of a difference one would see if they use the hottest water they can get out of their tap. It would still be a “cold” sparge compared to suggested, but if your tap water comes out at 120F there shouldn’t be such a massive drop in temp for the grain bed and could eliminate some of the issues with lower temp wort going into the boil.

If this was ever repeated, it’d be cool to see the same exbeeriment done with a heavy wheat/rye malt bill (30-50% wheat/rye) with a single infusion. Not that this is a criticism or anything, just curiosity about how a really sticky wheat/rye mash, or heavy adjunct mash (oats) would behave with a cool/cold sparge.

Buddy of mine uses water from a direct heat instant water heater – one of the on demand units. Makes some of the best beer around. He has it dialed up but maybe 120-140F max.

Totally off topic… Sorry

Where can I get some of those cool glasses?

They’re not currently available, but given the requests I keep receiving, I’m considering selling them. When this happens, I’ll be sure to announce it!

I do rinse with water that is around 170, but it ranges from 160 to 173 depending on how closely I’m paying attention. It do it because it doesn’t cost me any time. However, if I find I’m short of need water for the boil, I will just run cold water through the grain to make the difference I’ve only needed about a half gallon max. So, it seems immaterial. It hasn’t affected the beer in any way that I can tell.

I batch sparge. If the temp hasn’t reached 168ish by the time I need it, I sparge anyway. It is usually between 140-165 so I never worry about it.

Ditto

Could evaporation during the hot sparge have accounted for at least some of the volume difference?

It could have been a factor.

So is the next step on this subject to test this variable with fly sparging?

Perhaps if there is a demand or interest.

I don’t think there’s much use doing that one. If dumping a whole bunch of cold water onto hot water + mash has no discernible impact, then how would slowly trickling cold water over hot water + mash be perceptible? If anything, I would think the impact during fly-sparging would be less since the overall heat of the grain and water remains higher for a longer period of time (with a gradual lessening of the mash’s temperature over the course of the sparge-out) vs. an almost immediate change from ~155 to ~94 degrees.

Ray, have you guys done an xBmt for no sparge versus batch sparge? I saw one for batch sparge versus fly sparge, but nothing regarding no sparge.

Personally, I switched to no sparge a while back and it’s been a major improvement in my brew days. I don’t do BIAB, but do everything with two 15-gallon kettles (one mash, the other boil). I’ve heard it said that no-sparge is a less efficient method, but it’s not noticeable to me, at least at this scale. I was curious whether others have made a similar switch and if consumers could really tell the difference.

Marshall has done many batches that way, but no formal xbmt. My “grist Ratio” test would be VEEERY close, as that was very nearly no-sparge.

https://brulosophy.com/2016/02/15/the-mash-standard-vs-thin-liquor-to-grist-ratio-exbeeriment-results/

Very interesting experiment. Do you think the results would have been different if the ‘hot’ sparge had hit the target temp of 170 degrees? I’m pretty new to all-grain, but if that is the commonly accepted temp required to halt enzyme action, having two beers sparged at below-170 might explain the similarity of the final product. Interesting that, at least below the halt-enzyme-action threshold, the effect of sparge water appears to be negligible.

Hard to say. I’m inclined to think it probably does not matter.

Would dropping the temperature with a fold fly sparge stop the enzymatic activity in the same way as raising it to 170 for a mash out?

Huh. Huh.

Sorry I had to repeat that because now it calls in to question my standard BiaB batch sparge method. I typically use my 6 gallon pot for mashing and my 5 gallon pot for steeping. Usually split 2:1 in terms of water volumes between the pots. Mash for 45 minutes in the bigger pot, then steep at 165-170F in the smaller pot with the rest of the water, then combine. I notice slightly higher efficiency than trying to do it all in one pot and most importantly, it means I can do actual 5 gallon batches (anything over ~3.5 gallons, unless a VERY thin beer, just don’t fit mashing in my 6 gallon pot).

Now I wonder if there would be any noticeable difference going with tap temp water. It would make squeezing out the grains from the bag MUCH easier than trying to handle 160+F grains. That there might be something worth while on efficiency, time and well being.

It would also mean I could pretty easily steep multiple times, especially for BIG beers like a RIS. Like just yesterday I made a 3.5 gallon batch of 1.110 RIS. Filled my 6 gallon pot to the brim and my 5 gallon pot to the brim, between those and the grains, I ended up with 3.5 gallons of beer volume at the end of a 90 minute boil and my target gravity. If I had steeped the grains a second time, I might have been able to squeeze an extra 1-2 quarts of final volume, with the same final gravity (because I have no doubt there were sugars left in those grains since I only ended up with 70% efficiency, compared to my typical 1.05-1.07 OG beers, which hit about 80% efficiency). I probably also could have squeezed an extra 1 or 2 pounds of grains in to the pots and gone with that 2nd steeping. I also could have squeezed a little more wort out of the grains (I gave up after awhile because 20+lbs of grains when you include what they’ve soaked up, that are 160+ F is NOT fun to squeeze, nor to try to leave suspended).

Maybe instead of buying a 7 or 8 gallon pot, that is my way to 4 gallon RIS batches.

Try it!

Awesome! I just signed up to receive notices from your blog after following it for a while. As I did this I wondered, “Will he ever do something on sparge water temps?” Two days later you did!

This to me seems to be a BIG F-ing Secret in homebrewing. All recipes talk about grain bills, mash temps, and if you are lucky, efficiencies. But I have YET to see ANYTHING that says “Sparge at 170 degrees.” And everyone seems to automatically do this. Thanks for blowing the lid off on this mass assumption which, on the surface, seems to be like most mass assumptions: rather unfounded.

Interesting. My tap water comes about 50f if that. I always heat sparge water but I’m not bothered about the temperature. Anything above 100f or so will do.

I pondered the cool sparge until you mentioned the heat difference of the wort. It’s cheaper where I live to jack up the heat on an electric stove than to use LP to do the same.

One thing I didn’t see mentioned was the pH of the sparge water. If I am correct, this also affects the extraction of tannins if over 6.0 I think. Since you used the same water at different temps, this variable could not be analyzed, nor was it a factor. I would like to see a future exbmt highlighting this.

I do BIAB and sparge with cold water at the end of the mash. That way my hands aren’t burning while I’m squeezing the bag. When I started doing it, I saw a 5 point rise in my efficiency.

Exactly the same here!

I think an interesting aspect to this is that I could very easily switch to fly sparging from my batch sparge setup and not worry about the increase in time to heat cooler kettle wort. At the end of the mash I could simply rest a bucket of cold water above my MLT and start the flow, opening the flow into my kettle. Once I had a gallon or so collected the in the kettle I’d start heating that and if I time it right I’d be at a near boil by the time my fly sparge was done. hmmmm…

Interesting Xbeeriment, as usual. After seeing Kai’s work a couple years ago(and I believe Denny may have posted something in HBT forum as well), I have not been quite so diligent on heating all my sparge water. All depends on the volume I have in my HLT(my spare kettle). If I have all the sparge water I need heated to 170ish, great. If I need a little more, I dump some tap water in there. Thanks for confirming that what I’m doing is probably just fine.

i enjoy reading the xbeeraments and also the comments, both to which i can apply to my own brews. hot sparge, cold sparge, batch, fly, what about pressure? or step sparging in small batches? take a pump pressure sprayer, fill it with heated water and BLAST residual sugars from those pesky grains!

Interesting experiment! I’d like to add that what you call “cold water”(24°C) is one degree above room temperature here in Oslo, Norway. Last time we measured the cold water from tap it was 6°C – 42°F). That was in August/september… Therefore, whereas the lower ABV in your experiment isn’t really noticeable, it would be interesting to see what effect is has with *cold* tap water for those of us who live in the North. What I would have liked to see documented in the experiment was the actual temperature of the wort after sparging and ow much more time this took to reach boiling. In our situation, it is good to avoid the longer time to boil on an otherwise busy day, so that in itself is a good reason to use warm water. Especially since we’re in the kitchen anyway. (We also fill the Speidel with water the evening before)

Thank you for this exbeeriment. Next time I’m going to use “hot” tapwater (120*F/49*C) for batch sparging. So I don’t need to use my hot liquor kettle anymore.

Slightly off topic but I wanted to give a shout out to Ray for the killer recipe. Been sitting in a keg for about a week now and I just smashed 4 pints in a row. Damn tasty beer my brother..Cheers

What kind of sulfate to chloride ratio did you use for your water?