Author: Ray Found

Used to increase body, mouthfeel, and head retention in beer, dextrine malt is a staple ingredient in many breweries. Classified as a specialty malt since the process used to make it differs from those use to make standard base malts, dextrine malt is often mistakenly believed to be a very lightly colored Caramel malt. Indeed, Briess points out that while “Carapils kernels exhibit a glassy character from the starch that has been converted to dextrines and then dried, it is not a caramel malt.”

To be sure, there are multiple varieties of dextrine malt available to brewers, all produced using proprietary methods said to have an impact on the character it ultimately imparts in beer. For this xBmt, we chose to focus on one of the more popular dextrine malts, Carapils, which is produced by Briess Malting. Briess provides the following description of Carapils on their website:

Carapils Malt falls into the category of dextrine malts and is intended to improve body, mouthfeel and head retention by adding resistant dextrines, proteins, non-starch polysac-charides , and other substances to the wort and beer. Because of the crafted design, Briess Carapils is very effective in this regard and is intended to be used at 2-3% to show a positive effect.

I’ve personally used Carapils for the stated purpose in numerous beers, in fact it made up a small portion of the grist in all of my first few batches as a matter of course, when I generally thought of it as an insurance policy for good head retention– alongside acid malt for water manipulation, Carapils was the first grain I stocked in house, simply adding a few ounces to every grist on brew day. I brewed a few batches without it after running out of my supply at home and, noticing no shortcomings of foam, never resumed the practice. Curious if I was missing out on something, I decided to put it to the test.

| PURPOSE |

To evaluate the differences between a beer made with Carapils and an otherwise similar beer made without Carapils.

| METHODS |

Understanding that any effect on flavor was likely to be minor, I wanted to brew a very simple beer for this xBmt to make sure any differences would shine through and went with a Blonde Ale where 1 contained 10% Carapils and the other had additional base malt in its place, both of equal total weight. While Briess claims using Carapils at 2-3% of the grain bill will benefit head retention, they also state up to 10% can be used for certain applications, and since we sought to maximize the effect of the variable, that’s what I went with.

Citra Blonde Ale

Recipe Details

| Batch Size | Boil Time | IBU | SRM | Est. OG | Est. FG | ABV |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5.5 gal | 60 min | 46.5 IBUs | 4.2 SRM | 1.049 | 1.013 | 4.7 % |

| Actuals | 1.051 | 1.012 | 5.1 % | |||

Fermentables

| Name | Amount | % |

|---|---|---|

| Pale Malt, 2 row (Gambrinus) | 8.75 lbs | 87.5 |

| Carapils (Briess) | 1 lbs | 10 |

| Honey Malt | 4 oz | 2.5 |

Hops

| Name | Amount | Time | Use | Form | Alpha % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Magnum | 6 g | 60 min | Boil | Pellet | 12.1 |

| Citra | 30 g | 20 min | Boil | Pellet | 12 |

| Citra | 40 g | 5 min | Boil | Pellet | 12 |

| Amarillo Gold | 20 g | 5 min | Boil | Pellet | 8.5 |

Notes

| Water Profile: Ca 57 | Mg 0 | Na 8 | SO4 67 | Cl 55 |

Download

| Download this recipe's BeerXML file |

I started collecting RO water the evening prior to brewing in order to have my full volume ready the following day.

After making mineral adjustments, I began heating the water to my target strike temperature.

The relatively small grain bill made weighing out and milling the grains quick and easy.

It wasn’t until after milling both sets of grain noticed an interesting statement on the Carapils package: No flavor or color contribution. I guess we’ll just have to see about that.

Each batch underwent a separate full volume no-sparge mash with consistent temperatures between them.

Once each 60 minute mash was complete, sweet wort was collected, transferred to individual kettles, then brought to a boil where they remained for an additional 60 minutes. At the conclusion of each boil, the wort was quickly chilled to just above my current groundwater temperature.

The worts were then cast off into their own marked 6 gallon PET carboys.

At this point, I took hydrometer measurements to find the non-Carapils wort yielded a slightly higher OG compared the batch including Carapils, which was unsurprising given the slightly lower extract yield of Carapils.

While I waited for the worts to finish chilling to my target fermentation temperature in the cool chamber, I spun up a pair of matching vitality starters using WLP090 San Diego Super Yeast.

A starter was pitched into either batch a few hours later and I observed active fermentation the following day, both appearing quite similar.

After some time away from home for work, I returned to what appeared to be two batches of fermented in beer and took hydrometer measurements confirming FG had been reached in both.

I performed my typical routine of cold crashing and fining with gelatin before transferring the beers to kegs and force carbonating them in my cold keezer. Side by side samples of the ready beers showed not only that they were similar in terms of color and clarity, but that the batch made with Carapils had no better head retention or lacing than that batch made without it. In fact, it almost seemed as though the opposite were true.

| RESULTS |

At total of 11 people of varying levels of experience participated in this xBmt. Each taster was served 1 sample of the beer made with Carapils and 2 samples of the beer made with only base malt in different colored opaque cups then asked to select the unique sample. In order to reach statistical significance with this number of participants, 7 (p<0.05) would have had to make the accurate selection. However, only 2 (p=0.95) tasters accurate selected the Carapils sample as being unique, suggesting tasters were unable to reliably distinguish a beer made with Carapils from one made without the specialty malt.

Indeed, the sample size for this xBmt was smaller than we usually aim for, an issue I blame on the fact the beers were really tasty. While I personally avoided the taps to maintain supply for data collection, my attempts to encourage similar restraint by my wife and house guests was clearly ineffective. Extrapolating from a set of data isn’t going to give us a very powerful result, but I thought it was interesting to note that in order to reach statistical significance given the current data set, every single one of 9 additional participants would have had to correctly identify the odd-beer-out. While a response rate so far from what was observed isn’t impossible, it certainly is highly improbable.

My Impressions: I attempted 3 “blind” triangle tests and chose a wrong sample every time. Guessing wasn’t my strong suit this time. The beers were strikingly similar in every respect including mouthfeel and body, which is where I expected to notice any differences. What I found most interesting is that over multiple attempts where I poured various ways to produce head and watch for lacing, I simply could not get the beer made with Carapils to exhibit better foam qualities than the batch with all base malt. If anything, the opposite was the case, I observed the beer made without Carapils to have better foam stability and lacing, though those differences were minor and generally difficult to detect.

| DISCUSSION |

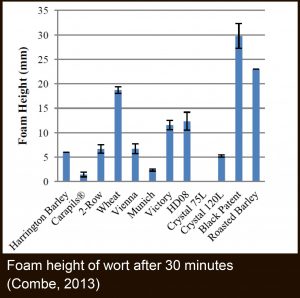

The fact participants in this xBmt were unable to reliably distinguish between a beer made with Carapils and one made without the malt not only confirms my own personal experience, but provides support for the notion Breiss puts forth that Carapils does not contribute to flavor or color in any appreciable way, even when used at 10% of the grain bill. However, I’m at a bit of a loss when it comes to the fact the beer made with Carapils had no better head retention or lacing than the beer  made without it, and furthermore, that tasters were unable to tell them apart based on mouthfeel and body. Considering some possible explanation for these results, perhaps the head retention benefits are only relevant in beers with notably poor foam without it, that the addition of Carapils may help to correct a foam-deficit, but not work in a cumulative sense for beers that already display “normal” foam qualities. Given our decision to use a higher amount of Carapils for this xBmt, I also wonder if there’s a point of diminishing returns whereby a smaller amount might produce a more noticeable effect. But this is all mere speculation, it could very well be that Carapils simply doesn’t do what we’ve been led to believe. In fact, these results align with studies performed at UC Davis demonstrating Cara- and Crystal malts generally aren’t foam positive.

made without it, and furthermore, that tasters were unable to tell them apart based on mouthfeel and body. Considering some possible explanation for these results, perhaps the head retention benefits are only relevant in beers with notably poor foam without it, that the addition of Carapils may help to correct a foam-deficit, but not work in a cumulative sense for beers that already display “normal” foam qualities. Given our decision to use a higher amount of Carapils for this xBmt, I also wonder if there’s a point of diminishing returns whereby a smaller amount might produce a more noticeable effect. But this is all mere speculation, it could very well be that Carapils simply doesn’t do what we’ve been led to believe. In fact, these results align with studies performed at UC Davis demonstrating Cara- and Crystal malts generally aren’t foam positive.

Since I had already eliminated the use of Carapils in my own brewing, this didn’t really give me any reason to reconsider that position. If I were still a regular user of this grain, I would likely be tempted to try a few batches without it to see if it resulted in any noticeable changes if only for the fact base malt is a little cheaper and stocking fewer grains is easier.

If you have any thoughts about this xBmt, please do not hesitate to share in the comments section below!

New Brülosophy Merch Available Now!

Follow Brülosophy on:

FACEBOOK | TWITTER | INSTAGRAM

If you enjoy this stuff and feel compelled to support Brulosophy.com, please check out the Support page for details on how you can very easily do so. Thanks!

47 thoughts on “exBEERiment | Dextrin Malt: Impact Carapils Has On A Blonde Ale”

Awesome stuff. I’ve often wondered about the 2.5% carafoam I’ve added to some of my beers, especially since I read an experiment somewhere that showed it is basically a Pilsner malt and can self-convert.

Does that graph indicate roast malts as foam positive?

Without solid evidence, flaked wheat has become my go-to foam enhancer. I am not sure why I don’t use malted wheat except that I really like flaked wheat mouthfeel–based on an inference that flaked wheat was the source of positive mouthfeel characteristics in my house saison.

Yes, dark malts give the foam. Seems to make sense. A lot of my dark beers seem to be really foamy:

“Wheat” is referring to wheat malt. I just looked up the article. That chart is a little misleading as well. It is actually extracts that have not been boiled. After boiling the extracts, the foam negative properties decreased. The crystals still had less foam than the others and the dark malts were still better though.

They also made four beers and tested the foam, 100% pale malt, 80% pale-20% crystal 75L, 80% pale-20% crystal 120L, 80% pale-20% crystal 150L. The crystal 150L beer gained the least from boiling the extract. They didn’t say, but I assume it was the worst foam of all of them as well. the 120L was clearly the worst foam of the 3 they showed the data for.

This foils my latest NE IPA trial if the carapils has no impact on mouthfeel! shoot! maybe i’ll try some wheat malt next time and see if it is foamier and more mouthfeel. Not sure if the two are associated or not.

The foam benefit in wheat is allegedly protein derived, and protein allegedly influences mouthfeel. These theoretical facts have probably led me to attribute my correlation of flaked wheat with foam and mouthfeel to a causal relationship.

I’ve certainly had foamy beers that have great mouthfeel but others that are more thin. Dark beers tend to taste fuller, thicker to me and most of the time have great head. I’ve also had Belgian Golden Strongs that have incredible, frothy head but seem more thin (in a good way) in mouthfeel. Maybe certain proteins are better for one or the other and some are good for both. One thing we can probably be fairly certain about is that dextrins in a beer don’t really contribute as significantly to mouthfeel or foam as some think.

Exact opposite of my findings, where even a few ounces of carapils would impact the mouthfeel in a recipe I’d been working on, only changing that variable. Very weird.

I recall once thinking a beer I made where I’d forgotten Carapils was thing and watery, but only after I realized I’d forgotten it. These days, I’m much more likely to accept that perception was more a function of confirmation bias than reality, at least if I’m not sampling the beers blind at the same time and relying on memory.

Do you think the the Gelatin pulled out the Proteins left from the Carapils as well as the yeast that you used has a higher flocculation rate and attenuation?

I try not to speculate on reasons for a given result or non-result.

Great write up. I to have given up on carapils. For my normal process of no sparge single infusion, I just add 5 to 10 % wheat malt. Works great. For Belgian styles, where we want a meringue like head, we do a step mash…

I’ve long thought Carapils is pointless. When making blondes/golden ales/lagers, I tend to have the opposite problem of too little body – my beers have too much mouthfeel and aren’t crisp and light enough. I think it makes more sense to lighten the body rather than boosting it, using adjuncts such as maize or rice to lower the level of dextrins and malt proteins in the final beer.

Nobody here in the UK seems to use Carapils much, but that may be because the most popular pale malt (Maris Otter) has more than enough body already.

ph data becomes required in this experiment. Both boil and final. Head retention would have been fine with the grist provided, perhaps try 40% rice in a cereal cooker. Mouth feel would be the parameter to test here but the final gravities tell me it was a wash.

I don’t think pH data becomes required… Maybe a few more tries to see if it’s repeatable, but if people can’t distinguish the difference, who cares if there is one or not? It’s the perception that counts at the end of the day.

Interesting results. At least we can say that Carapils did not help in this case. I’d be curious with a different style that’s known to not have very good head.

I feel like you used the wrong mash temp to see any difference with CaraPils.. I tend to only add it to beers that I mash low for a dry finish, but want to add just a touch of body. Mashing the whole batch at 152 will probably provide more body than the Carapils would have.. I’m now curious to see if you might notice a difference when mashing at 148.

This is an excellent point, but why not just mash a few degrees higher instead of using carapils?

Briess contends that there is more to Carapils than dextrins, which would make a higher mash temp nonequivalent:

http://blog.brewingwithbriess.com/understanding-carapils/

Seems lame that the images they show at this site do not have any controls. It’s just 4 beers with Carapils in them…

Carapils adding this and that is one of those things that seemed bogus from day 1 of homebrewing, thank you for confirming it!

Interesting that the roasted malts provide better foam stability. It explains why my Red IPA had really impressive head and lacing compared to my base IPA. I literally used the exact same recipe, the difference being 2-3% roasted barley for color. The beer had such good foam stability that the head remained til the glass was almost empty.

For the exbeeriment, maybe you should have tried mashing a lot lower, like 148 and using less hops. From my own research, I remember reading somewhere that heavily hopped beers have much better foam stability from the get go. I kinda expected to see something like 20-30 ibu’s in your recipe. I’m sure the beer tasted awesome as-is though.

I haven’t used carapils for a few years and have never felt that I lacked anything from mouthfeel to head retention.

Once again, interesting stuff. Recipes with dextrine/caraPils seem to be hit or miss wrt foam quality. However, I have notices a consistently good quality of foam quality with 4-8% malted wheat (IPAs, Schwarzbier, stouts)

What was the mash PH? 5.5-ish?

Not to be nitpicky here but your FG were 1.014, not 1.012, right? At least that’s what your images suggest. Still identical, just a bit higher.

The hydrometer used has a .002 correction factor. Have new one now!

I have used Carapils in the past but never seemed to give me the results I expected. I will admit to being a novice brewer who is a bit frenetic at trying new ingredients and processes. Thanks for the write up – I do enjoy reading about your exbeeriments.

Great post. Just wanted to clarify why carapils and caramel malts are associated. Both start out the same way. Green malt (germinated barley, not yet dried) is stewed between 149-158F to convert starches into sugars inside the grain. The difference is that after stewing carapils is simply dried at low temperatures 131-140F (Briggs, Malts and Malting) while caramel malts are made by kilning at a higher temperature range 248-320F. Since the sugars in carapils are not “caramelized” you can say it’s not a caramel malt but as far as the process goes, it’s in the same category.

I agree with Dean. I use Carapils or Carafoam (whatever I have on hand) ONLY when I do step mashes and/or decoctions. Wonder what your results would have been if you mashed at 130-140?

Here is a great video presentation of Dr. Bamforth talking about the cited literature from UC Davis: https://youtu.be/w8uisMqvhho?t=59m41s

This is a Private Video on youtube and cannot be accessed.

Here’s something to consider. As a brewer who routinely makes session strength beers, I’m always looking for ways to get the same body with lower alcohol content. It strike me that both beers had similar body, but the carapils beer had a lower starting gravity (and thus a lower abv). In other words, the carapils allowed you to achieve a beer indistinguishable from one with a higher OG and ABV. Just a thought.

The elephant in the room for me is “dextrins”.

If starches are converted into dextrins by alfa-amylase, and dextrins are converted into simple sugars by beta-amylase, and you mash in extra dextrins, what will that ultimately leave from those dextrins? Because from the start of the mash, the beta-amylase will be very busy working on converting all dextrins.

So, what would the point be of adding extra dextrins at the beginning of the mash?

Excellent point! Any effect can’t be due to “normal” dextrins. Maybe if they are modified is some was rendering them poor substrate for beta-amylase=

Briess claims Carapils contains much more than dextrins.

That’s a good point. Briess claims that their Carapils does not have any unconverted starch or any amylase enzyme activity, but the other base malt grains do, So the dextrins in Carapils could presumably be converted to fermentable sugar by beta amylase. When added to an extract brew, the dextrins should remain in the wort (assuming no ordinary malt or enzymes added) but not necessarily in an all-grain brew.

I have a tangential question about your equipment, so my apologies in advance for that.

What is the pH of your RO water at first, before you begin building it out with salt additions? I’ve always found in numerous places I’ve lived that home RO systems produce very low pH water, like < 4.0. This has caused me problems when trying to use RO water for brewing, so I'm curious if you have a different experience with that particular system you pictured.

Cheers!

pH of water is sort of irrelevant, since the water has no real buffering power – pH is like voltage, it tells you something about the nature, but doesn’t say much about how much power is actually there (amperage) to do anything with the effect of that voltage.

Right, RO should have very little buffering power, so it should be easy to raise the pH to a proper level, at least that’s what I’ve gleaned when trying to research it. But given that most of the brewing salts we use tend to lower pH, rather than raise it, could this still be a problem?

The problem is almost never needing to raise pH… the base malt will get you to nearly 6.0 with RO water on its own. We want to lower to 5.2-5.5 with acid/minerals/dark malts. For very dark beers (say darker than amber), alkalinity must be added to RO water (lime, bicarbonate) to buffer acidity from dark malts.

Seriously, I have never, ever, ever taken the pH of my water. I input it as 100% RO in Bru’n water, slap on my malts and mineral/acid adjustments, and EVERY TIME my measured pH has been within ~.05 of the estimated value.

the water itself will just go whichever way it is blown by acid, malt, minerals… it has no “backbone” to resist.

Ok, right on. I use bru’n water, so I’ll do a batch with my RO as you’ve suggested and see how it goes. I appreciate your time & input!

Could you guys do another xbmt in this vein using some other supposed body or head enhancing malt/grain, such as wheat malt, to see if it shows a difference/

This article has some major issues that I’m surprised no one brought up yet. In the results section, in the first sentence, you mention only 2 people participated in the xbmt. That can’t be right. Then you immediately go on to say you served one cup of beer with w34/70 yeast and two beers with s-189 yeast. What? I thought this xbmt was about carapils. Why are you also changing the yeast strain? Earlier in the article you mentioned you fermented both beers with wlp090 so which is it?

Was 11 participants, not 2… but something is wonky – I am not sure where all that stuff about various yeasts came from… that wasn’t in the original as published. Only 2/11 got it right. All was WLP090.

Really interesting, started using cara-pils with my extract brews (250g) all have been excellent. However my local brew shop has stopped selling it those small quantities as it “makes no difference”. Like a lot of brewers, if it works, I don’t mess with it… first two without Cara-pils in buckets now, keen to see the difference. Thanks a lot for the article, keep up the good work.

Beer with 50% Catapils grist tested here:

http://scottjanish.com/dextrins-and-mouthfeel/

could a poor quality carapils malt give a caramel flavor? I made some batchs with this malt and i’m not sure if it’s the malt or maybe diacetil. :/

I guess I would be interested in trying this with a recipe that tended to end up overattenuated. My first attempts at all-grain I used a two step mash 30 min at 142 and 60 at 152. With both of my first two attempts I got ridiculously low FG (1.002) and way overshot my projected ABV by about 2%. Obviously I had a highly fermentable mash. A recipe that yields this kind of attenuation seems to be the place to try Carapils in order to leave some unfermentable sugar.

Great experiment topic.But the choices of malt (ale) and yeast (ale) probably represent when you would not use dextrin malt additions, to my limited knowledge, I would have tried with pilsener malts not ale and further used a lager yeast…perhaps s23. In any case I would love to see you do the same experiment (preferably with a lager) using maltodextrin, Cheers Dave