Author: Jordan Folks

There are a number of things that go into producing a quality batch of beer, though one that gets a lot of attention from brewers is yeast pitch rate. Referring to the percentage of live yeast cells in a given population, higher viability is associated with cleaner fermentations with a lower risk of off-flavors, hence the common recommendation to pitch multiple yeast packs or propagation in a starter.

However, many brewers believe that some beer styles actually benefit from being pitched with a lower cell count, as the added stress encourages the yeast to produce certain desirable characteristics. One such example is Saison, which like other Belgian ales, is noted for possessing a unique fermentation profile featuring rather strong phenol and ester notes.

I’m a nut for doing things the right way and always pitch the “proper” amount of yeast, which amounts to 0.75 million cells per milliliter (mL) per degree Plato (°P) for ales. Well, almost always, as I’ve been slightly underpitching (0.5 million cells/mL/°P) my Belgian ales as a means of coaxing out more fermentation character. While recently designing a Saison recipe, I began wondering how much of an impact yeast pitch rate has and designed an xBmt to test it out.

| PURPOSE |

To evaluate the differences between a Saison that is underpitched (0.5 million cells/mL/°P) and one that is overpitched (1.0 million cells/mL/°P).

| METHODS |

Wanting any yeast character to shine through, I designed a simple Saison recipe for this xBmt. Big thanks to F.H. Steinbart for hooking me up with the malt for this batch!

Bumpy Plane Ride

Recipe Details

| Batch Size | Boil Time | IBU | SRM | Est. OG | Est. FG | ABV |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5.1 gal | 60 min | 28.7 | 5 SRM | 1.058 | 1.006 | 6.83 % |

| Actuals | 1.058 | 1.006 | 6.83 % | |||

Fermentables

| Name | Amount | % |

|---|---|---|

| Extra Pale Pilsner | 9 lbs | 66.67 |

| Barke Vienna Malt | 4 lbs | 29.63 |

| Wheat Malt, Pale | 8 oz | 3.7 |

Hops

| Name | Amount | Time | Use | Form | Alpha % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hallertauer Mittelfrueh | 57 g | 60 min | Boil | Pellet | 2.2 |

| Tettnang | 57 g | 30 min | Boil | Pellet | 1.8 |

| Tettnang | 50 g | 5 min | Boil | Pellet | 1.8 |

Yeast

| Name | Lab | Attenuation | Temperature |

|---|---|---|---|

| Rustic (B56) | Imperial Yeast | 76% | 68°F - 80.1°F |

Notes

| Water Profile: Ca 59 | Mg 10 | Na 10 | SO4 99 | Cl 44 |

Download

| Download this recipe's BeerXML file |

After collecting the full volume of water for two 5 gallon/19 liter batches, adjusting each to the same desired profile, and getting them heating up, I milled the grain.

Once the waters were properly heating, I incorporated the grains and performed the same step mash on each with a 45 minute rest at 144°F/62°C followed by a 30 minute rest at 160°F/71°C followed by a 10 minute rest at 170°F/77°C.

During the mash rests, I weighed out the kettle hop additions.

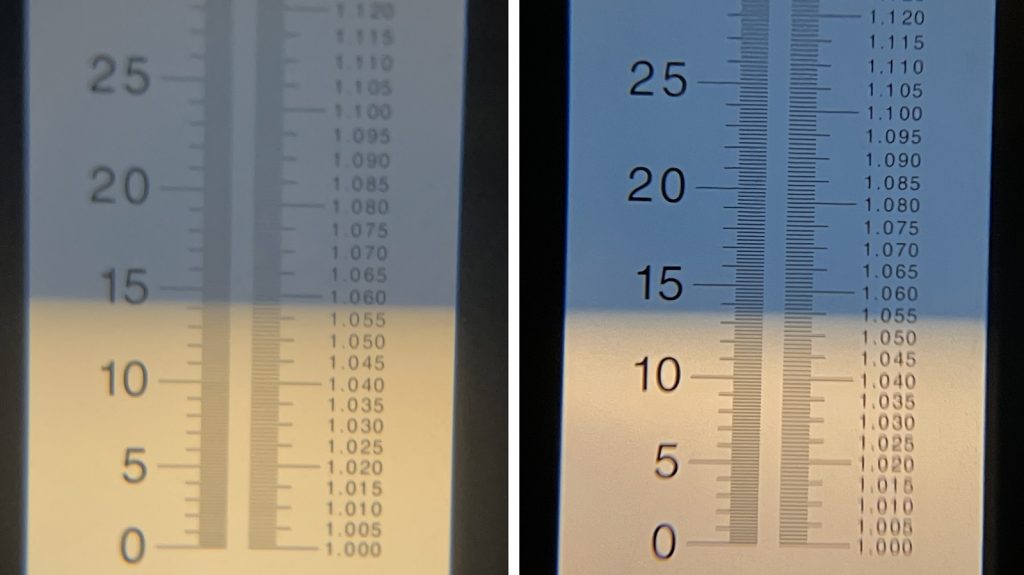

When the boils were complete, I chilled them during transfer to separate fermentation kegs before taking refractometer readings showing a small 0.003 OG difference.

At this point, I pitched 300 mL of Imperial Yeast B56 Rustic slurry that was harvested from a prior batch into one wort while the other received 600 mL of the same slurry, resulting in predicted pitch rates of 0.5 and 1.0 million cells/mL/°P, respectively.

The beers were left to ferment in a spot that maintains a steady at 66°F/19°C for a week before I began gradually raising the temperature to 80°F/27°C over the following 2 weeks, at which point I took hydrometer measurements showing the beers were at slightly different FGs that aligned with the OG difference.

With the beers done fermenting, I pressure transferred each to separate bottling kegs dosed with enough priming sugar to achieve a hearty 3.2 volumes of CO2, then proceeded with bottling under pressure.

After 2 weeks of conditioning at 78°F/26°C, I placed bottles in the refrigerator and let them chill for a few days before they were ready for evaluation.

| RESULTS |

A total of 20 people of varying levels of experience participated in this xBmt. Each participant was served 2 samples of underpitched beer and 1 sample of the overpitched beer in different colored opaque cups then asked to identify the unique sample. While 11 tasters (p<0.05) would have had to accurately identify the unique sample in order to reach statistical significance, only 8 did (p=0.34), indicating participants in this xBmt were unable to reliably distinguish a Saison pitched with 0.5 million cells/mL/°P from one that was pitched with 1 million cells/mL/°P.

My Impressions: Out of the 10 semi-blind triangle tests I attempted, I correctly identified the odd-beer-out just 4 times, which isn’t consistent enough to indicate much. To me, both of these beers had similar notes of pepper, spice, and everything nice.

| DISCUSSION |

Whereas a higher pitch rate is generally viewed as being requisite for the production of clean beers, when making Belgian ales with more fermentation character, many brewers treat it more as a lever with lower pitch rates resulting in higher phenol and ester development. Interestingly, tasters in this xBmt were unable to reliably distinguish a Saison pitched with 0.5 million cells/mL/°P from one that was pitched with 1 million cells/mL/°P.

It’s well established that yeast stress is associated with the production of certain fermentation byproducts, and that one avenue of such stress low pitch rates. One possible explanation for these results is that, despite being under the recommended pitch rate, the yeast from the underpitched batch was viable and vital enough to minimize any additional phenol and ester production.

Ultimately, the fact these beers were indistinguishable by both participants and myself served to reinforce my belief that there’s a lot of wiggle room when it comes to producing Belgian ales. While I’ll continue leaning into to lower pitch rates when making such styles, I look forward to experimenting with even more extreme pitch rate differences in the future.

If you have any thoughts about this xBmt, please do not hesitate to share in the comments section below!

Support Brülosophy In Style!

All designs are available in various colors and sizes on Amazon!

Follow Brülosophy on:

FACEBOOK | TWITTER | INSTAGRAM

If you enjoy this stuff and feel compelled to support Brulosophy.com, please check out the Support page for details on how you can very easily do so. Thanks!

22 thoughts on “exBEERiment | Yeast Pitch Rate: Underpitch vs. Overpitch In A Saison”

Hi there! The difference might have been too small. Anyway it’s a nice experiment and showed something many brewers related. I only found that a underpitched fermentation starts slower than a proper or overpitched (in homebrew scale it’s possible if you throw the wort directly to a yeast cake, in consecutives batches).

Besides the experiment itself, could you share with us your perceptions about this beer? Taste, aroma, mouthfeel… It’s always nice to read someone’s else opinions about a style.

Keep brewing and experimenting!

I popped a bottle last night – this beer is tasting fantastic right now (a couple months since bottling). The yeast is allegedly sourced from Dupont – and sure enough, the beer tastes very Dupont-esque (spicy, herbal, crisp, refreshing, bright, dry, appropriately bitter, clove-forward, a whisp of sulfur on the nose). Highly recommend this recipe if you’re looking for a tasty Belgian-inspired Saison. Unfortunately, Imperial no longer sells Rustic to homebrewers, so you’ll have to acquire a Dupont strain elsewhere (that is to say, I do not think this beer would taste the same if French Saison yeast was used).

Imperial’s classic Dupont strain is actually Filibuster (saddly also not available to homebrewers). Rustic is the strain used at Brasserie Blaugies, which was selected from a yeast bank in Brussels. Supposedly this strain is similar to what Dupont uses, but is noted for having a slightly different profile and more reliable attenuation during fermentation.

Right. I heard a rumor that Dupont actually co-pitches four strains, and Wyeast’s 3724 (which is presumably the source for Imperial Filibuster) is isolated from one of those four strains – that might explain why this strain is notorious for the “Dupont stall” when fermented on it’s own. Relatedly, I heard a rumor that Blaugies gets their yeast from Dupont. So my theory has been perhaps Rustic is a component of Dupont’s yeast blend. In fact, my favorite Saisons have used co-pitches of Rustic and Filibuster. Perhaps I’ve been misinformed – but this beer was quite Dupont-esque!

Estimating cell count by volume is ok. Professional brewers go by weight, although it is less accurate at smaller scales. The best method, as I’m sure you know, is to conduct an actual cell count. This could confirm your results – perhaps in a different style?

I would like to see this experiment repeated with a much greater difference and utilizing new less than 1 month old yeast from the manufacturer. I would recommend 0.5 Mcells/ / ml/ degree plato for the low pitch rate and 1.5 to 2 million cells for the overpitch. Also while small the FG difference is important. I suggest making one wort and split

Belief Meets Reality. Reality wins again. The Universe just doesn’t care what we believe.

Thanks for the experiments. Keep up the good work.

I’m not surprised that no one could tell the difference with the two variables being so similar. What would have happened with one packet of dried yeast vs the 600ml of slurry?

I had heard of this but seemed too complicated to test and control. I prefer to focus on temperature as the main way to shape the profile of my belgian beers and still don’t always succeed !

This may have beer a very good beer. But it is not a Saison. Saison is like a French Lawnmower beer and should not exceed 5%. Coming in at close to 7% is out of style. I am sure it would fit into a different category like an Imperial Double Saison….

According to BJCP

https://www.bjcp.org/style/2021/25/25B/saison/

It would be a Standard Saison.

ABV

3.5 – 5.0% (table)

5.0 – 7.0% (standard)

7.0 – 9.5% (super)

Anywhere from 3.5% to 9.5%? So, meaningless.

But what about Saison Dupont thats 6.5%?

Hey Jordan, the beer sounds great! I just had a couple (wall of text) comments.

A few other commenters have already mentioned this, but readers seem to be frustrated with every Brulosophy pitch rate experiment because the “under-pitch” batch is hardly an under-pitch and tree over-pitch batch is barely an over-pitch, resulting in only a small difference in pitch rate.

In this case, both batches may have been an over-pitch. So maybe the experiment was really comparing a slight over-pitch with a slightly greater over-pitch.

https://byo.com/article/defining-yeast-slurries-dealing-overcarbonated-keg-mr-wizard/

If we’re really trying to learn something, why not just go for it? In other words, why not exaggerate the variable in question to force a difference and then subsequently reduce the delta until any difference disappears.

I once did a split batch experiment with cultured yeast from a commercial bottle. One batch got a grown up “normal” starter-sized pitch, and the other batch got only the bottle dregs of a single bottle. The “normal” pitch batch tasted regular and boring, but the bottle dregs batch tasted like Juicy Fruit gum.

Maybe you can try something like that next time? For example, maybe a full pint from a mason jar in one batch and maybe a teaspoon from that exact same mason jar for the other batch.

The other thing that seems to frustrate a lot of readers and commenters is the presence of so many confounding variables that would be trivial to fix. In this case, for example, these batches really should have been from the same initial wort. Sure, you can probably brew two relatively consistent batches within reasonable tolerance limits, but why not simply remove the variable from the equation? It would be so easy. Another example in this case is that apparently two different collections of yeast were used. Sure, they were probably collected similarly and stored in similar locations, but they weren’t connected the same and stored in the same location. On other experiments, brewers tend to do something similar by using two separate commercial yeast packages without homogenizing. I’m sure things like this are driving all the science people in your audience crazy!

Either way, thanks for putting in the time and sharing with us! Cheers!

Well said.

The write-up indicates that both slurries were collected from the same batch.

My gripe here is that the write-up suggests an awful lot of certainty that pitch rates of 1 million and 0.5 million cells/mL/P were achieved. But cell counts weren’t done, so the best that can be said is that, assuming the slurries were well-homogenized, one batch got twice as many cells as the other. There is no way to know in this experiment what the actual pitch rates were.

Right, they were collected from the same batch separately, then stored separately in separate containers, and then apparently not homogenized prior to use. Homogenizing would eliminate even the remote chance that the separate handling of these yeast slurries matters. And the thing is… it probably doesn’t actually matter, but it’s trivially easy to use cleaner experimental practices.

Actually, the yeast culture used in the xbmt came from a single jar/source. First, I calculated the estimated viability using a yeast calculator given the slurry harvest date. Next, I used Wyeast’s recommendations for estimating cell counts based on slurry dilution. I then discounted the estimated cell count of the jar based on the predicted viability. Conveniently, the 900ml of slurry I had was estimated to achieve approximate pitch rates of .5 and 1.0 when split into 300ml and 600ml respectively (given my OG/batch size). I homogenized the slurry as best as I could, and then poured 300ml into a separate jar. Then each jar was pitched into the respective FVs. I think criticisms of cell count accuracy are fair, but I leveraged industry literature to get as accurate of an estimated cell count as I could given my lack of a microscope.

I really feel that the quality and quality control of yeast manufacturers has grown by leaps and bounds over the last 15-20 years, to the point where the pitch rate guidelines of old are probably quite a bit higher than needed with modern yeasts. I pitch about 1/4-1/3 of my typical pitch rate to get the level of expression I’m looking for out of ester-forward yeast strains. “Recommended” pitch rates are an overpitch for me in those styles.

To truly test out this variable, I’d recommend using 1/4 the recommended rate as an “underpitch” and double the recommended rate as an “overpitch”. Given the exponential growth rate of yeast, it’s really not surprising to me that a factor of two difference in pitch rate led to a non-significant result.

1004/6 that’s a our 6 to 8 points before finishing fermentation.

998 or less is what you aime for.

saison is a diastaticus son al sugars will ferment and some moment

Well done Jordan and thank you for a nice exbeeriment! You need thick skin to be a Brülosophy contributor. Reading the comments was more entertaining than the lab report. lol

Lets remember that this is home brewing not research.

I wonder could you please explain your reasoning behind the bottling procedure? It seemed to involve several stages, and I’m not sure exactly why they were there? Why transfer to a keg and then pressure fill? do you mean with a counter pressure filler like a beer gun?

If I bottle condition I just dose each bottle with the same amount of a sugar solution and rack the beer straight from FV to the bottle. Job done!

My bottling procedure is actually quite easy, given the equipment I have.

The process: Fill a keg with non-foaming sanitizer. Push the sanitizer out with co2. Fill the purged keg with the requisite amount of sugar solution to reach desired carbonation for the entire batch. Co2 purge the keg a few times. Use co2 to close transfer the beer from the fermentation keg to the bottling keg. Use a Blichmann Beergun to co2 purge a bottle, fill bottle via Beergun, purge head space, cap. Store bottles in a warm chamber set to 78°F/26°C for two weeks. Refrigerate and enjoy.

The reason: 1) I’m fermenting in kegs, so might as well use co2 to push things around (since I easily can) instead of introducing oxygen via opening the top and racking out of it. 2) My bottling bucket is for sour beers, so I avoid using it to bottle non-sour beers.