Author: Andy Carter

Most of the methods used by small batch homebrewers were adapted from those employed by larger commercial brewers, and while the main production processes are largely identical, there are a number of factors posited to impact the ultimate quality of beers based on batch volume. As it relates to fermentation, homebrewers contend little with issues such as the impact of hydrostatic pressure, which is absolutely a point of consideration as batch volume increases.

As the organism responsible for turning wort into beer, brewers tend to be rather focused on ensuring their yeast is as healthy as possible, as off-flavors are one result of yeast being in stressful environments. Whereas the hydrostatic pressure in smaller homebrew batches is around 15 psi, it can be upwards of 35 psi in larger commercial fermentation tanks, ostensibly putting increased stress on yeast.

With a past xBmt indicating tasters were unable to reliably distinguish a Barleywine fermented in a 3 gallon/12 liter carboy from one fermented in a 5 gallon/19 liter carboy, I was curious how things might pan out with a more extreme difference in volume. For this xBmt, I partnered with my friends from Tarantula Hill Brewing to see how fermenting 5 gallons/19 liters might differ from a 5 bbl fermentation of the same pale lager.

| PURPOSE |

To evaluate the differences between an American Light Lager fermented in a 5 gallon/19 liter vessel and one fermented in a 5 bbl vessel.

| METHODS |

Known for being a style of beer that doesn’t hide flaws well, we went with an American Light Lager recipe for this xBmt.

Tarantula Hill Lite Lager

Recipe Details

| Batch Size | Boil Time | IBU | SRM | Est. OG | Est. FG | ABV |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5.5 gal | 30 min | 10.3 | 3.4 SRM | 1.041 | 1.005 | 4.73 % |

| Actuals | 1.041 | 1.005 | 4.73 % | |||

Fermentables

| Name | Amount | % |

|---|---|---|

| Pilsner Malt | 8 lbs | 80 |

| Torrefied Wheat | 2 lbs | 20 |

Hops

| Name | Amount | Time | Use | Form | Alpha % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Perle | 11 g | 60 min | Boil | Pellet | 7.9 |

Yeast

| Name | Lab | Attenuation | Temperature |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dry Lager | Tarantula Hill Slurry | 77% | 46°F - 55.9°F |

Notes

| This recipe was scaled down from 5 bbl to 5 gallons |

Download

| Download this recipe's BeerXML file |

While brewed on a larger commercial system, this brew day started off just like usual with the collecting of water that was adjusting to our desired profile, after which we milled the grain.

Once the strike water was adequately heated, we combined it with the grist then set the controller to maintain a mash temperature of 148°F/64°C.

While the mashes were resting, we prepared the kettle hop additions.

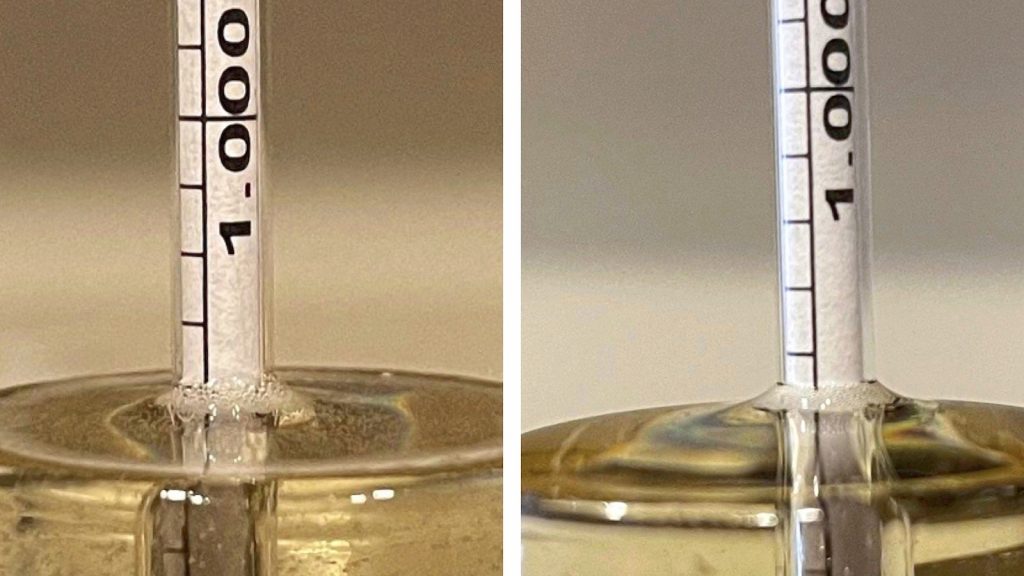

Once the mash and sparge steps were complete, the wort was boiled for 40 minutes and chilled to 50°F/10°C before a refractometer reading confirmed it was at the target 1.041 OG. After transferring the wort to a 5 bbl tank, the yeast was pitched and left for about an hour to homogenize, after which 5 gallons/19 liters was transferred to my Delta FermTank.

I promptly took the small batch of wort home and placed it in my chamber controlled to 55°F/13°C, the temperature Tarantula Hill ferments this beer at.

I followed a similar fermentation schedule as Tarantual Hill that involved 2 weeks at 55°F/13°C then a 3 week lagering period at 33°F/0.5°C, after which a hydrometer measurement showed it was slightly lower than the 1.008 FG target.

I proceeded to pressure transfer the beer to a sanitized keg, adding 25 mL of Biofine Clear, which matched the rate Tarantula Hill used in the 5 bbl batch.

The filled keg was placed in my keezer to continue lagering on gas for an additional 3 weeks before the beers were ready for evaluation.

| RESULTS |

A total of 21 people of varying levels of experience participated in this xBmt. Each participant was served 1 sample of the beer fermented in small volume and 2 samples of the larger volume beer in different colored opaque cups then asked to identify the unique sample. While 12 tasters (p<0.05) would have had to accurately identify the unique sample in order to reach statistical significance, 14 did (p=0.002), indicating participants in this xBmt were able to reliably distinguish an American Light Lager fermented at a volume of 5 gallons/19 liters from one fermented at a volume of 5 bbls.

The 14 participants who made the accurate selection on the triangle test were instructed to complete a brief preference survey comparing only the beers that were different. A total of 2 tasters reported preferring the beer fermented at a volume of 5 gallons/19 liters, 11 said they liked the beer fermented at a volume of 5 bbls, and 1 had no preference despite noticing a difference.

My Impressions: Out of the 5 semi-blind triangle tests I attempted, I correctly identified the odd-beer-out 4 times, which while not perfect, is consistent enough to indicate I perceived a difference. To me, the beers looked mostly the same, though the head was a touch rockier and more persistent on the 5 bbl batch. While both had a pleasant fresh baked bread aroma and flavor with little hop presence, the 5 bbl version was perceptibly drier and more bitter than the slightly sweeter 5 gallon/19 liter batch. In the end, my preference was for the version fermented by Tarantula Hill.

| DISCUSSION |

When comparing homebrew and commercial beers, it’s often said that certain perceptible differences are “a matter of scale,” one being that the larger batch volumes made by commercial brewers puts more pressure on yeast compared to smaller homebrew sized batches. While this is undeniably true, there remains some disagreement about idea that this pressures impacts yeast behavior such that they produce different flavor characteristics in beer. Providing some confirmation of this claim, tasters in this xBmt were able to reliably distinguish an American Light Lager fermented at a 5 gallon/19 liter volume batch size from one fermented at a 5 bbl batch size.

Of the numerous aspects of the brewing process, fermentation is widely regarded as being one of the most important when it comes to the overall character beer, hence the importance brewers place on yeast health. The fact fermentation batch volume had a perceptible impact on this simple pale lager suggests this particular factor may play more of a role in beer character than many presume, indicating yeast performance may be influenced by fermentation volume.

This is one of those variables that I’ve been curious about for a long time, as I’ve definitely wondered about how batch size impacts beer character. Given the significant findings here, along with my own ability to tell these beers apart, I’m comfortable accepting that fermentation volume may in fact have an impact, and I look forward to doing similar comparisons in the future.

If you have any thoughts about this xBmt, please do not hesitate to share in the comments section below!

Support Brülosophy In Style!

All designs are available in various colors and sizes on Amazon!

Follow Brülosophy on:

FACEBOOK | TWITTER | INSTAGRAM

If you enjoy this stuff and feel compelled to support Brulosophy.com, please check out the Support page for details on how you can very easily do so. Thanks!

26 thoughts on “exBEERiment | Impact Fermentation Volume Has On An American Light Lager”

One of the more interesting exBeeriments, thank you! Would love to see a version of this where the yeast contributes significant flavor to the beer such as a Belgian beer.

I wonder if the results would have been the same if the 5 bbl batch used the slurry, and the 5 gallon batch would have used a fresh pitch of the yeast. Could the yeast in the slurry have been use to the pressure from being used before and better adapted to the pressure?

This experiment has inspired me to try this with my pressure capable fermentors. Thanks! 😃

When you scaled the recipe, did you account for the greater bitterness extraction brewing at larger scale is believed to cause? It’s possible the difference is more due to a higher IBU?

A good point, a change in bitterness upon scale up at the commercial scale is well known and understood. Mostly due to higher residence times at around 100 C

So, there is a 60 minute addition but only a 30 minute (or is it 40) boil? Is there something I am missing?

Very intriguing experiment. I wonder what other factors might have played a role besides hydrostatic pressure. For instance, how do you know that the yeast concentration was equivalent in the 5 gallon sample that you took from the 5 bbl fermenter? Fewer yeast cells would likely account for the difference perceived.

But…. You fermented the beer on a non-pressurized system and they used their regular system which I guess is pressurized?

Interesting experiment, nice to be able to collaborate with a commercial brewery for it! There is a second variable that is massively different aside from fermentation volume for this experiment that is not mentioned, and given your tasting notes, they would suggest that it is likely the source of the tasting differences between the two batches. Your packaging processes would have been quite different (both process and equipment) and seeing as an increased sweetness and reduced hop impact are some of the first signs of oxidation, I would suggest that a difference in O2 pickup during packaging was more likely the reason for noticeably different results. I’m not suggesting beer ruining levels of oxidation, but just enough to cause the slight decrease in hop presence and increase in apparent sweetness of your home packaged batch.

The experiment still proves the same result (that scale/equipment can impact taste), just the description of the tested element needs to be broadened to truly incorporate the range of the difference “Impact fermentation and packaging scale/equipment has on an American Light Lager (home brew vs commercial)”.

Cheers!

In the introduction, this “experiment” is framed as a test of hydrostatic pressure as the independent variable. In the discussion, it’s mostly about batch volume. Which is it? They are not the same independent variable, and they are most definitely not interchangeable. (And I will hold my tongue on how this “experiment” in no way had a single independent variable.)

How long does it take to chill and transfer wort in a home-brew setup vs a commercial system?

Arguably the 5 barrel system would have resulted in slower cooling and transfer times. Which means more hop contact time in the kettle and more IBUs. That would explain the bitterness difference between the two beers. I would think a difference in IBUs would be very perceptible.

Fantastic exbeeriment! Maybe for the next one you can try to match the pressure by fermenting on the homebrew scale at around 10 psi?

Great article, interested to see the difference. Would it be worthwhile to compare the batches using chemical tests – IBU EBC pH FAN polyphenol? I can do it for you if you send the samples.

What about oxygen? It could explain the difference in attenuation and perceived bitterness.

There was no difference in attenuation….?

Nice exbeeriment. It reminds me that there are lots of variables going on in this (all) biological experiment(s); some we test for and many we don’t, can’t, or are simply unaware of.

How do you figure a homebrewer sees 15 psi hydrostatic pressure? It would take a liquid column of roughly 30 feet to develop 15 psi.

Yeah I submitted the same comment on Monday afternoon, but it never got posted. I assume it got blocked because it’s not uber-flattering to the Brulosophy folks. We’ll see if this comment gets posted…

Hi there. Your comment wasn’t blocked and is now visible on the site. In order to filter out spam comments (we get a ton), all first time commenters require approval, after which their comments will post immediately. Sorry about the delay, we appreciate any feedback, even if it’s not uber-flattering.

A liquid column of just 2ft will create 15psi at the bottom.

No, 2 feet of wort will create roughly 1 psi of hydrostatic pressure.

And I mean gauge pressure, not absolute pressure.

I’d honestly love to know what led you to think this is true. There seems to be a fascination with hydrostatic pressure I’ve never understood and maybe your rationale is a clue. Kyle is right (comments about absolute/relative aside), approx 2.3 ft / psi (depending on gravity). So in particular, for this xbmt where the 5 bbl fermenter appears to be only a few feet taller than the 5 gal, the pressure at the bottom of the 5 gal is probably close to mid-vessel pressure in the 5 bbl, and all of that at the 17-18 psia (2-3 psig) range.

This statement: “Whereas the hydrostatic pressure in smaller homebrew batches is around 15 psi” is somewhat misleading if not completely false. Conventionally, in my experience, hydrostatic is taken as gauge pressure (ie excluding the atmostpheric pressure all things experience all the time) not absolute, so in a typical 5 gallon ferementation vessel the top is as zero, the cone is a 2-3 psig, unless you’re ferementing under pressure and I don’t see any reference to that here, and the vessel used appears to have a max rating of 4 psi.

A vented commercial fermeter 30 ft tall would approach 15 psi at the bottom.

So I’m always curious about where the concern around pressure comes from.

Interesting that they ended at the same final gravity, but the large volume batch was perceptively drier. Any thoughts on why? Does carbonation level play any part? I always want to get my lagers to that dryness level I cannot seem to get.

Donkeypox and build back better shirts when I open the link? Kelp your god damn politics to yourself!!

Just a heads up– the single AdSense ad we run on each article shows ads based off of each user’s personal online activity, we don’t set that. For example, when I visit the site, I see ads for things like Hawaiian t-shirts and slip-on shoes, nothing political at all.

This is a nice experiment of the difference between fermenting and packaging with a good home setup, and a commercial one, but it is NOT an experiment that can give any clue about the influence of the fermentation volume. The confunders are simply to many, and are likely to have a greater influence on their own.