Author: Mike Neville

While opinions about clarity in beer have shifted given the rise in popularity of certain notably hazy styles, there exists a segment of brewers who continue to hold brightness in high esteem. Some of the most common causes of haze in beer, such as tannins and remnant yeast, hold a negative electric charge, meaning they are attracted to substances with a positive charge, which results in large enough clumps forming that they more readily fall out of solution, thus clarifying the beer.

A rudimentary yet effective beer fining agent is gelatin, a product derived from animal collagen that, when mixed with water, becomes positively charged. One method for fining with gelatin involves first chilling the fully fermented beer to 50°F/10°C or lower, adding the solution directly to the fermentation vessel, then letting it sit for a day or so before packaging. However, many brewers find it’s more convenient to fine once the beer is in the keg, claiming it’s equally as effective as fining in the fermenter, though some worry that the larger amount of sediment in the serving vessel may impact the quality of the beer.

Fairly soon after I started brewing, I developed a strong desire to produce the clearest beer possible and adopted the practice of fining with gelatin. Unable to effectively cold crash in the fermenter at the time, I usually added the gelatin solution to the beer once it was in the keg and let it sit a couple days before pulling off those first few sludgy pints. Since purchasing a glycol chiller, I’ve been fining in the fermenter, but I couldn’t help but wonder what, if any, impact fining in the keg has on beer quality.

| PURPOSE |

To evaluate the differences between a Kölsch that was dosed with gelatin fining in the fermentation vessel and one that was dosed with gelatin fining in the keg.

| METHODS |

Wanting to ensure any differences were readily apparent, I went with a simple Kölsch recipe for this xBmt.

Morning Shift

Recipe Details

| Batch Size | Boil Time | IBU | SRM | Est. OG | Est. FG | ABV |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5.5 gal | 60 min | 42.8 | 3.2 SRM | 1.051 | 1.011 | 5.25 % |

| Actuals | 1.051 | 1.011 | 5.25 % | |||

Fermentables

| Name | Amount | % |

|---|---|---|

| Pilsner | 9 lbs | 90 |

| Vienna Malt | 1 lbs | 10 |

Hops

| Name | Amount | Time | Use | Form | Alpha % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Triumph | 21 g | 60 min | Boil | Pellet | 10.7 |

| Kazbek | 43 g | 20 min | Boil | Pellet | 4.3 |

| Kazbek | 14 g | 20 min | Boil | Pellet | 5.5 |

Yeast

| Name | Lab | Attenuation | Temperature |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dieter (G03) | Imperial Yeast | 77% | 32°F - 32°F |

Notes

| WATER - Ca 52 | Mg 7 | Na 5 | SO4 26 | Cl 54 |

Download

| Download this recipe's BeerXML file |

After collecting the water for a single 10 gallon batch, I weighed out and milled the grain.

With the water properly heated, I incorporated the grains then checked to make sure the mash was at my target temperature.

During the mash rest, I prepared the kettle hop additions.

Once the 60 minute mash rest was finished, I batch sparged to collect my target pre-boil volume then proceeded to boil the wort for 60 minutes, adding hops at the times listed in the recipe.

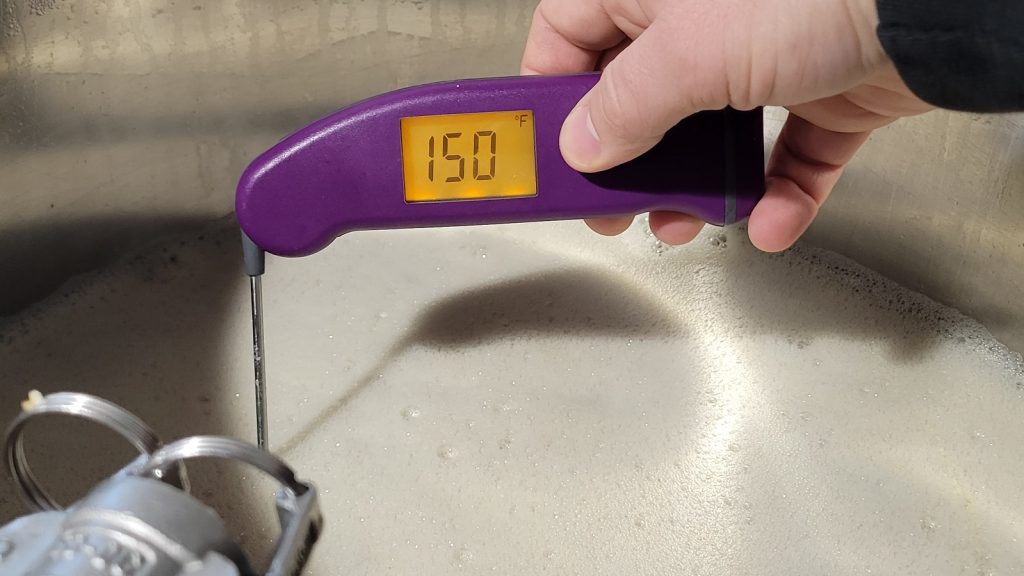

When the boil was complete, I quickly chilled the wort.

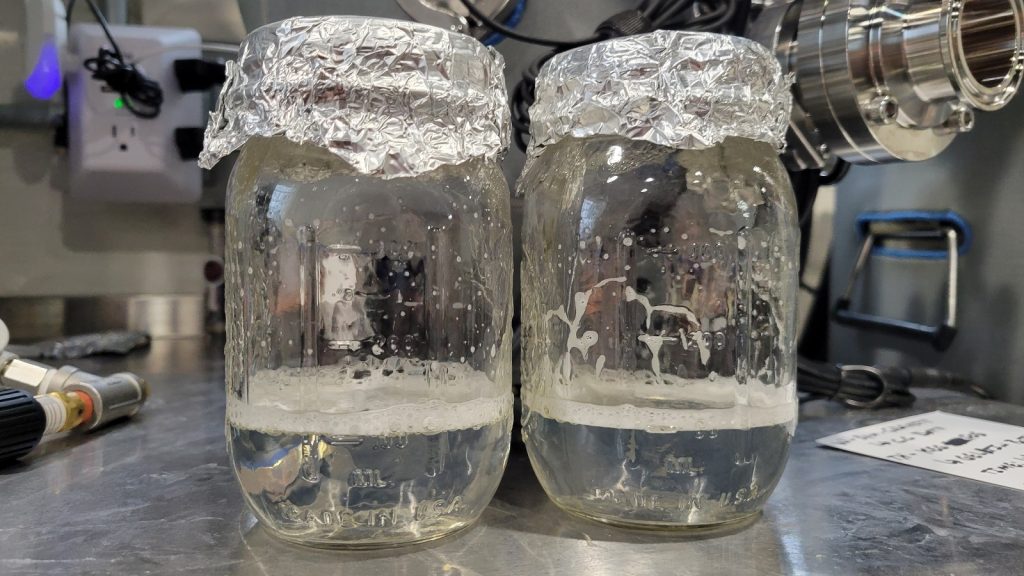

Next, I transferred identical volumes of wort to separate fermenters.

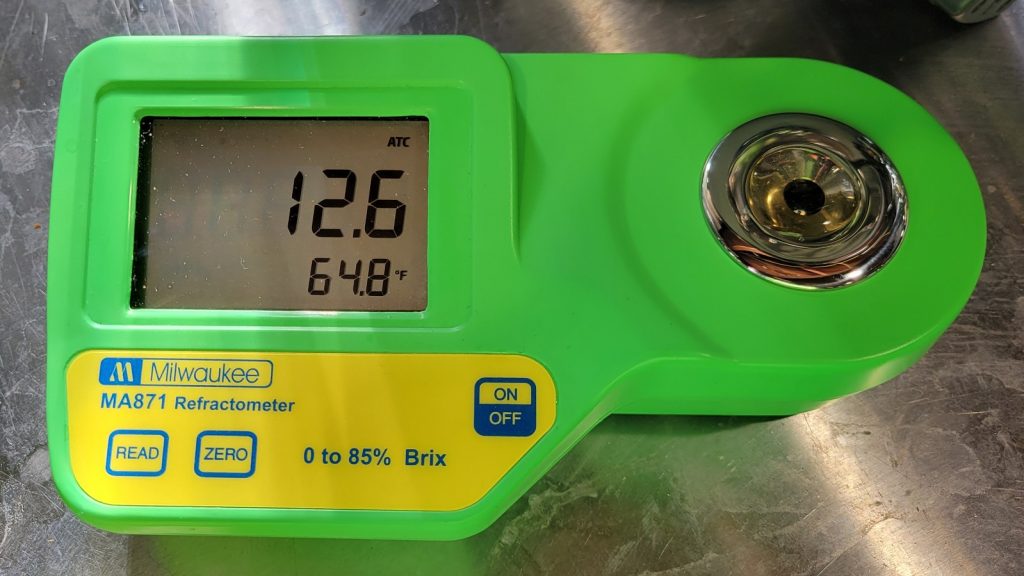

A refractometer reading showed the wort was at my target OG.

The fermenters were connected to my glycol unit and allowed to finish chilling to my desired fermentation temperature of 63°F/17°C, at which point I pitched a single pouch of Imperial Yeast G03 Dieter into each batch.

The beers were left to ferment for 10 days before I took hydrometer measurements showing both had reached the same FG.

I reduced the temperature of both beers to 38°F/3°C and left them alone overnight before pressure transferring one of the beers to a CO2 purged keg.

Next, I prepared 2 identically sized fining solutions by dissolving 2 grams of gelatin powder into 100 mL of warm water, at which point I added they were added to their respective beers.

The filled keg was placed in my keezer, which I keep at the same 38°F/3°C that the beer in the fermenter was being held at. After 48 hours, I proceeded to pressure transfer the beer fined in the fermenter to a CO2 purged keg, which was placed next to the other keg in my keezer. After 4 weeks of conditioning, I returned to purge the trub from the beer fined in the keg and found it ran clear after tossing approximately 3 sludgy pints, whereas the first pint from the batch fined in the fermenter was mostly clear.

| RESULTS |

A total of 28 people of varying levels of experience participated in this xBmt. Each participant was served 1 sample of the beer fined with gelatin in the fermenter and 2 samples of the beer fined with gelatin in the keg in different colored opaque cups then asked to identify the unique sample. While 15 tasters (p<0.05) would have had to accurately identify the unique sample in order to reach statistical significance, only 10 did (p=0.46), indicating participants in this xBmt were unable to reliably distinguish a Kölsch that was fined with gelatin in the fermentation vessel from one that was fined with gelatin in the keg.

My Impressions: Out of the 5 semi-blind triangle tests I attempted, I correctly identified the odd-beer-out just once. These beer were identical to me in terms of aroma, flavor, and mouthfeel, both being crisp, clean, and very drinkable. However, while difficult to tell from the pictures, the beer that was fined in the fermenter had slightly more haze than the one fined in the keg.

| DISCUSSION |

For many brewers, even those who appreciate a good Hazy IPA or Weissbier, clarity continues to be something much desired, particularly when it comes to certain styles. Mechanical filtration options are certainly effective, though they tend to be rather pricey, which is why many opt for chemical solutions including gelatin. While it’s commonly recommended to add gelatin fining to fermentation vessel, as it allows the beer to be packaged with minimal trub, many brewers choose to fine in the keg. The fact tasters in this xBmt were unable to reliably distinguish a Kölsch fined in the fermenter from one fined in the keg suggests any differences were minor enough as to be largely imperceptible.

One reason some choose to fine in the keg is to intentionally avoid cold-crashing in the fermenter as a way of preventing suck-back, thus reducing the risk of cold-side oxidation. For this xBmt, I cold-crashed both batches under CO2 pressure, but it’s possible those who don’t have the ability to do this could expose their beer to oxygen, which would add benefit to the practice of packaging beer warm then chilling and fining it in the keg.

I’ve been a fan of fining with gelatin for years and noticed no negative impact when I switched from adding it to the keg to adding it to the fermenter. While I was surprised to see that the beer fined in the keg was slightly clearer than the one fined in the fermenter, it was such a minimal difference that I have no plans to revert back and will continue fining in the fermenter, though I won’t hesitate to toss some gelatin into a keg of stubborn beer when needed.

If you have any thoughts about this xBmt, please do not hesitate to share in the comments section below!

Support Brülosophy In Style!

All designs are available in various colors and sizes on Amazon!

Follow Brülosophy on:

FACEBOOK | TWITTER | INSTAGRAM

If you enjoy this stuff and feel compelled to support Brulosophy.com, please check out the Support page for details on how you can very easily do so. Thanks!

16 thoughts on “exBEERiment | The Gelatin Effect: Impact Fining In The Keg Has On A Kölsch”

Isn’t gear maintenance, namely the beer faucets and keg poppets, the reason why you wouldn’t want to put gelatin in your keg? I thought I remember a listener submitted feedback say they had a big clot looking thing in their faucet?

I’m interested to hear how people’s gear holds up after a year of fining in the keg. Fining in the fermenter would obviously make it hard to reuse yeast.

This is anecdotal, but I’ve been using gelatin in my kegs for the past 5 years. I’ve never experienced a clog or build up in faucets, poppets, or disconnects. I disassemble my disconnects and faucet after every beer and run cleaner backwards through the poppets. Maybe if the regular maintenance isn’t kept up with you could get gelatin build up.

I’ve never had an issue with faucets or poppets clogging strictly because I used gelatin in the keg. I find that if I do my best to only transfer beer from the fermenter to the keg, the particulate that drops out of solution after fining in the keg has no problem making it’s way back out. I’ve only ever had poppets clog up on me if I transferred too much trub and/or hop particulate to the keg (fining or not).

Since adopting keg fermentation with a floating dip tube, fining has been worry-free for me with no transfers to worry about (closed or otherwise). Plus I never have to worry about suckback since the keg can be on gas while cold crashing. Simplicity itself.

Came here to say the same thing – floating dip tubes simplify keg finings quite a bit. Transferring warm, cold crashing in the keg, and fining in the keg is a super simple method, and is what I do for all my beers that aren’t super oxygen sensitive.

So, the gelatin was added to the keg and to the fermenter, but the fermenter was transferred to a keg after 48 hours and proceeded to sit for the balance of 4 weeks. In essence, one beer was fined for 4 weeks while the other was fined for 48 hours. Got it.

Right. The idea being does the beer sitting on that larger amount of sediment have an impact over time.

It’s not about the sediment, it’s about the gelatin mixture. The contact time of gelatin with the beer will flocculate and grab the particles over time. If you transferred from the fermenter to the keg, you left the gelatin behind whereas the gelatin in the keg from the start will be more effective.

For sure, the effectiveness of the gelatin is another piece of this but was not really the intent of the xBmt. The batch that got the gelatin in the fermenter was allowed to sit at cold crash temps for 48 hours before being transferred to the keg. My experience has been that gelatin works fairly quickly. From an appearance standpoint, these beers were nearly identical with the batch that got the gelatin in the keg was more clear just ever so slightly.

I’m interested in how the gelatin was added to both vessles. How did you avoid oxygen ingress>

I hooked up co2 to the fermenter, opened the 4″ lid, turned on the co2 so it was continuously pushing out, dumped the gelatin, and reattached the lid. Same process for the keg.

Never believed fining was worth the effort. Plus why add basically impurities to you beer

As Eric said,use a floating dip tube. You won’t get any sediment until the keg is basically empty. Gelatin still actually works at fermentation temperatures too. I’ve never cold crashed my beers. They’re not chilled until they go in the kegerator. I’ve used both methods and they both work fine with no blockages

When you are adding gelatin to the beer in the kegs does it matter if the beer is carbonated? Will it make any difference on being able to clear the beer?

That’s a good question. I’ve never added gelatin to an already fully carbonated keg. I wonder if dumping in the gelatin solution might create nucleation sites making the beer foam up. Sounds like a good xBmt to try out!

I pressure ferment all my beers (that don’t require dry hopping) with enough pressure (25-28psi @ 66-70F) to be fully carbonated by the end of fermentation. I gelatin fine all my beers after cold crash before transfer to keg. I do all of this under pressure though, I do not open the top once it is closed after yeast pitch. My beers do not have any exposure to oxygen until poured into a glass from the tap. No foaming issues, and crystal clear pours every time.