Author: Andy Carter

International Bitterness Units (IBU) offers an estimation of the bitterness in a beer based on the amount of alpha acids in hops as well as how long they are in contact with boiling wort. When brewers talk about the balance of a beer, they’re often referring to the interplay of sweetness and bitterness imparted by malt and hops, respectively. One tool brewers use to gauge the balance of a beer is the ratio of bitterness to gravity (BU:GU), which is determined by dividing a beer’s IBU by its OG—the closer to 1.0 that number is, the more balanced the beer will be.

It’s been widely claimed that the typical person is capable of perceiving a difference of just 5 IBU, so long as the total bitterness of the beer is under the upper threshold of perception of 100 to 110 IBU, as noted by Garret Oliver in The Oxford Companion to Beer. While bitterness is often viewed as a component of flavor, some contend it’s more of a mouthfeel thing where differences can be perceived regardless of other characteristics in the beer.

With one past xBmt showing tasters could not tell apart beers bittered to the same IBU with different hop varieties added at the beginning of the boil, while tasters in two other xBmts were able to distinguish beers bittered to the same IBU with the same hop variety added at different times during the boil, I began to wonder about the claim that a delta of just 5 IBU is perceptible. Curious to see for myself, I designed an xBmt to compare beers hopped with different amounts of the same variety added at the same time in the boil to achieve differing IBU levels.

| PURPOSE |

To evaluate the differences between American Blonde Ales bittered with different amounts of the same hop variety for the same amount time to achieve a 12 IBU difference.

| METHODS |

For this xBmt, I went with a very simple Blonde Ale recipe with a single hop addition at 60 minutes, one receiving double the amount as the other to result in a 13 IBU difference.

Humorous Humulus

Recipe Details

| Batch Size | Boil Time | IBU | SRM | Est. OG | Est. FG | ABV |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5.5 gal | 60 min | 24.6 | 6 SRM | 1.051 | 1.006 | 5.91 % |

| Actuals | 1.051 | 1.006 | 5.91 % | |||

Fermentables

| Name | Amount | % |

|---|---|---|

| Pale Ale Malt 2-Row | 10 lbs | 99.07 |

| Caramel Malt 60L | 1.5 oz | 0.93 |

Hops

| Name | Amount | Time | Use | Form | Alpha % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Liberty - 20 g or | 40 g | 60 min | Boil | Pellet | 5.5 |

Yeast

| Name | Lab | Attenuation | Temperature |

|---|---|---|---|

| Flagship (A07) | Imperial Yeast | 77% | 32°F - 32°F |

Notes

| Water Profile: Ca 96 | Mg 8 | Na 6 | SO4 128 | Cl 85 |

Download

| Download this recipe's BeerXML file |

I started my brew day by adding identical volumes of RO water to separate BrewZilla units then setting the controller to heat it up.

After adding the same amount of minerals to each kettle, I milled the grains into separate buckets.

Once the water for each batch was adequately heated, I incorporated the grains then checked to make sure both were at the same target mash temperature.

While the mashes were resting, I prepared the kettle hop additions.

Once each 60 minute mash was complete, I sparged to collect the same pre-boil volume then boiled the worts with hops added at the times stated in the recipe. While one batch received 20 grams of Liberty to achieve approximately 12 IBU, the other was hit with 40 grams of Liberty to achieve approximately 25 IBU (per Tinseth formula). At the end of each boil, the worts were chilled during transfer to fermenters.

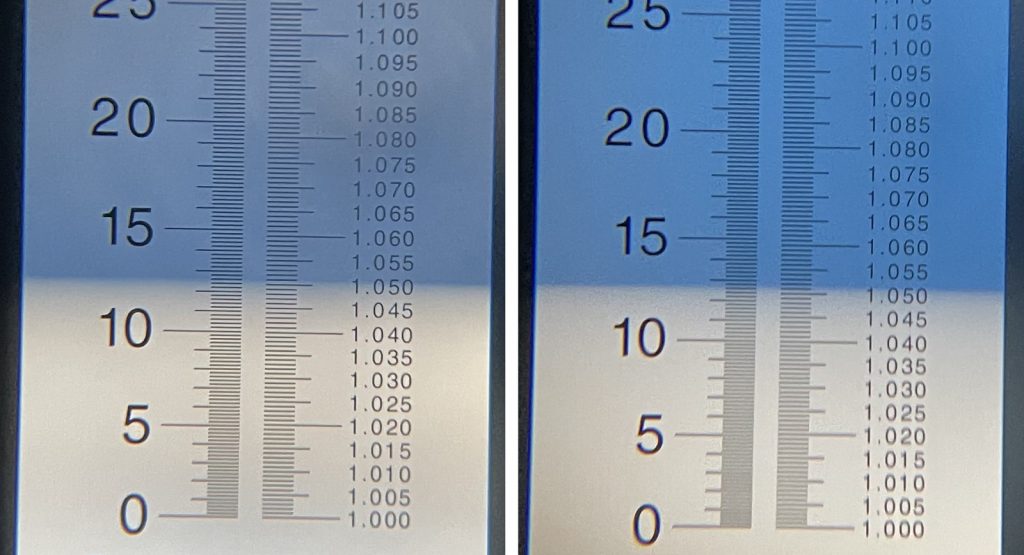

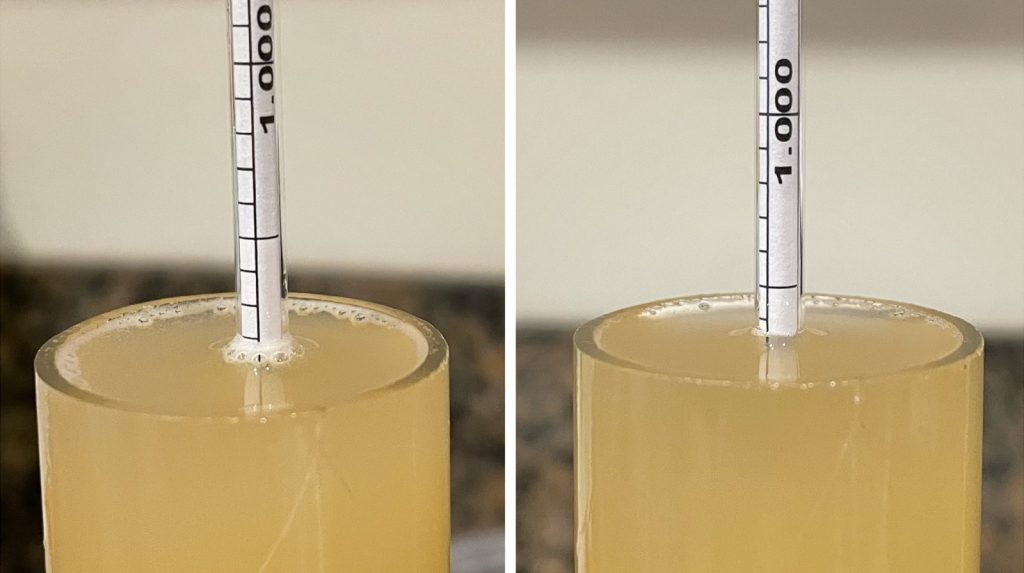

Refractometer readings showed both worts achieved the same target OG

The filled carboys were placed in my chamber and left to finish chilling to my desired fermentation temperature of 64°F/18°C for a few hours before I pitched a pouch of Imperial Yeast A07 Flagship into each.

After a few days, I raised the temperature in the chamber to 70°F/21°C and let it sit for another week before taking hydrometer measurements showing a the low IBU beer finished 0.002 SG points higher than the beer with double the IBU.

At this point, I pressure transferred the beers to sanitized kegs.

The filled kegs were placed in my keezer and left on gas for 3 weeks before they were ready for evaluation.

| RESULTS |

A total of 14 people of varying levels of experience participated in this xBmt. Each participant was served 2 samples of the low IBU beer and 1 sample of the high IBU beer in different colored opaque cups then asked to identify the unique sample. While 9 tasters (p<0.05) would have had to accurately identify the unique sample in order to reach statistical significance, only 6 did (p=0.31), indicating participants in this xBmt were unable to reliably distinguish a Blonde Ale bittered to 12 IBU from one bittered to 24 IBU with different amounts of the same hop variety added at the same time during the boil.

My Impressions: Out of the 5 semi-blind triangle tests I attempted, I correctly identified the odd-beer-out every time, which I have to believe was largely a function of my knowledge of the experiment. The beers were incredibly similar, nearly identical in every respect, but I perceived the low IBU beer as having a slightly less harsh bitterness that faded more quickly, allowing a bit more malt character to come through compared to the high IBU version.

| DISCUSSION |

IBU is one of the many tools brewers regularly use to predict the outcome of a beer, and seeing as bitterness is a quintessential component of nearly every style, the ability to make an accurate prediction is quite important. While conventional wisdom states most people can perceive a difference of just 5 IBU, tasters in this xBmt were unable to reliably distinguish a Blonde Ale bittered to 12 IBU from one bittered to 24 IBU with different amounts of the same hop variety added at the same time during the boil.

When contemplating the implications of these results, it’s important to consider the fact all existing IBU formulas are predictive in nature, meaning there could be some discrepancy compared to a proper lab analysis. Still, the fact tasters couldn’t tell apart a low IBU Blonde Ale bittered with half the amount of hops as its high IBU counterpart certainly goes against expectations, particularly given the simple recipe that offered little to hide behind.

In the years I’ve been brewing, I’ve always relied on IBU formulas to help guide when and where to make my kettle hop additions, which I plan to continue doing. I was unquestionably surprised by the results of this xBmt, and while it inspired me to want to continue exploring bitterness, I have no plans to change my approach at this point.

If you have any thoughts about this xBmt, please do not hesitate to share in the comments section below!

Support Brülosophy In Style!

All designs are available in various colors and sizes on Amazon!

Follow Brülosophy on:

FACEBOOK | TWITTER | INSTAGRAM

If you enjoy this stuff and feel compelled to support Brulosophy.com, please check out the Support page for details on how you can very easily do so. Thanks!

9 thoughts on “exBEERiment | Low vs. High IBU In A Blonde Ale”

There is a mistaken premise in the first paragraph: “One tool brewers use to gauge the balance of a beer is the ratio of bitterness to gravity (BU:GU), which is determined by dividing a beer’s IBU by its OG—the closer to 1.0 that number is, the more balanced the beer will be.” Having the BU:GU close to 1 does not indicate Balance. In fact, the vast majority of beer styles have a BU:GU of 1:2, Balance is a perception of the interplay of malt sweetness to hop bitterness, and the criteria of the ratio of what that balance should be varies by style. A Double IPA’s ratio would be close to 1:1 but an Amber Ale would be closer to 1:2, while a APA may be closer to 3:4.

I honestly struggle with the common idea that (hop) bitterness and (malt) sweetness somehow “balance” one another. Sweetness and bitterness don’t “counter” one another, and many beers (read: IPAs) are simultaneously too sweet and too bitter. There’s no balance to be had if the beer is too sweet (or too bitter).

This is some good work. Thanks.

Great experiment! It would be interesting to run this experiment in a group twice. Run it once without telling tasters the variable in question, collect that data, and then tell every one to taste again, telling them that the amount hops was the variable.

In the methods you say 13 IBU difference, but the theoretical values are 24 and 12, so the difference would 12 IBU.

Also – hop utilization doesn’t scale linearly. I don’t think any of the common IBU calculators take this into account. So while doubling the grams will increase it significantly, it will be a bit less than double. Probably not enough to mess up your experiment, but more likely you are comparing 12 to say 22 or 23 IBU. (If you used 10 g of 5% AA and 10 g of 10% AA – this should scale more linearly)

Honestly, it depends on the beer, but I think in many beers you’d need a 20 IBU difference for most causal beer drinkers to notice. I think you are right, that knowing the variable can help you identify something like this.

I would also love to see this repeated and hear the brewer perceptions with a closer to 1:1 sulfate-to-chloride or even chloride-favored water. Great stuff!

Wow! I think this goes to show how difficult the act of tasting really is. Triangle tests are hard!

This is an interesting experiment. I think it makes a nice contrast to this experiment on two beers with essentially the same IBUs but one brewed with a hop that had high cohumulone and the other with a low value hop.

https://brulosophy.com/2016/03/07/bittering-hops-high-vs-low-cohumulone-exbeeriment-results

In that experiment, a significant number of tasters could recognize the difference.

I’d suspect that the cited 5 IBU difference threshold for tasters detecting a difference is also sensitive to overall bitterness i.e. I’d think a lot more tasters would detect a difference between 20-25 IBU than could detect a difference between 80-85 IBU.