Author: Andy Carter

Malted barley contributes the majority of fermentable sugars to most beers and can be manipulated into infinite combinations of color, flavor, and mouthfeel. However, there are other commonly used cereal grains in brewing including flaked maize, also known as corn, which developed a bad rap among craft and homebrewers due to its relatively heavy use in mass market pale lagers. Over the last few years, it seems brewers have begun to realize how useful this adjunct can be, leading to a reduction in the overt hate directed toward corn.

The notion that brewing with flaked maize will result in a beer with corn flavors is completely understandable, and considering the dimethyl sulfide (DMS) off-flavor is often described as having a creamed corn character, it makes sense that people would avoid using it. Conversely, many users of flaked maize have reported it to be much more subtle in character than barley malt while adding similar levels of fermentable sugar, thus boosting alcohol without contributing flavor or body.

The results from one past xBmt showed tasters could reliably distinguish a Pilsner made with flaked maize from one made with just barley malt, though preference for each beer was split and nobody noted any corn flavors. Seeing as flaked maize is a key ingredient in Cream Ale, I designed an xBmt to test this variable out again on this refreshing style.

| PURPOSE |

To evaluate the differences between a Cream Ale made with all barley malt and one made with a portion of flaked maize.

| METHODS |

To ensure any impact of the variable would be on full display, I designed two simple Cream Ale recipes where one was made with all barley while the other had 21% flaked maize.

Corn Rules Everything Around Me

Recipe Details

| Batch Size | Boil Time | IBU | SRM | Est. OG | Est. FG | ABV |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5.8 gal | 60 min | 12.7 | 2.8 SRM | 1.048 | 1.006 | 5.51 % |

| Actuals | 1.048 | 1.006 | 5.51 % | |||

Fermentables

| Name | Amount | % |

|---|---|---|

| Pale Malt | 7.5 lbs | 78.95 |

| Flaked Maize OR Additional Pale Malt | 2 lbs | 21.05 |

Hops

| Name | Amount | Time | Use | Form | Alpha % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hallertauer Mittelfrueh | 28.3 g | 60 min | Boil | Pellet | 3.8 |

Yeast

| Name | Lab | Attenuation | Temperature |

|---|---|---|---|

| Harvest (L17) | Imperial Yeast | 74% | 32°F - 32°F |

Notes

| Water Profile: Ca 96 | Mg 8 | Na 6 | SO4 128 | Cl 85 |

Download

| Download this recipe's BeerXML file |

I started my brew day by adding identical volumes of RO water to separate BrewZilla units then setting the controller to heat it up.

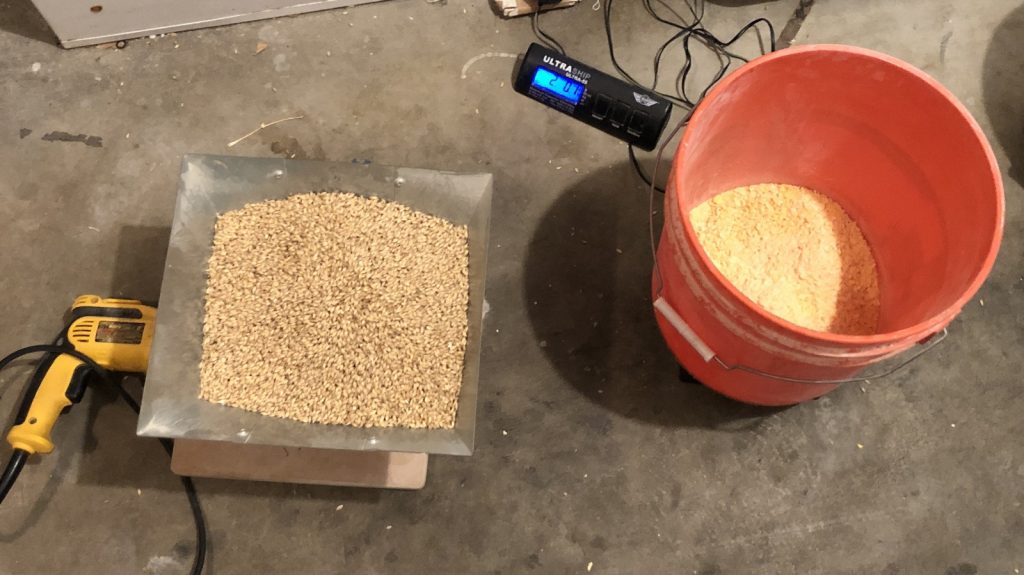

After adding the same amount of minerals to each kettle, I milled the grains into separate buckets.

Once the water for each batch was adequately heated, I incorporated the grains then checked to make sure both were at the same target mash temperature.

While the mashes were resting, I prepared the kettle hop additions.

Once each 60 minute mash was complete, I sparged to collect the same pre-boil volume then boiled the worts for 60 minutes before running them through a plate chiller.

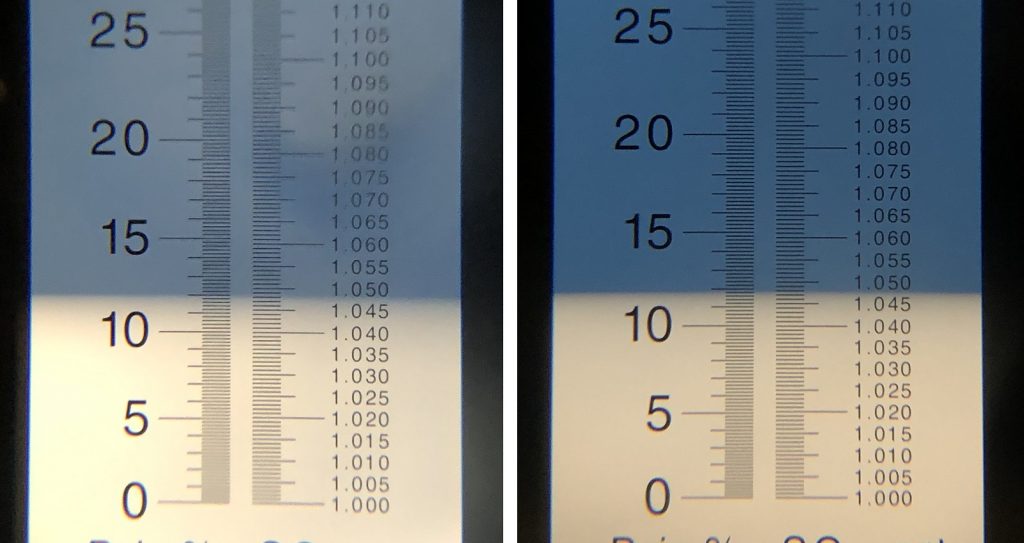

Refractometer readings showed both worts achieved the same target OG

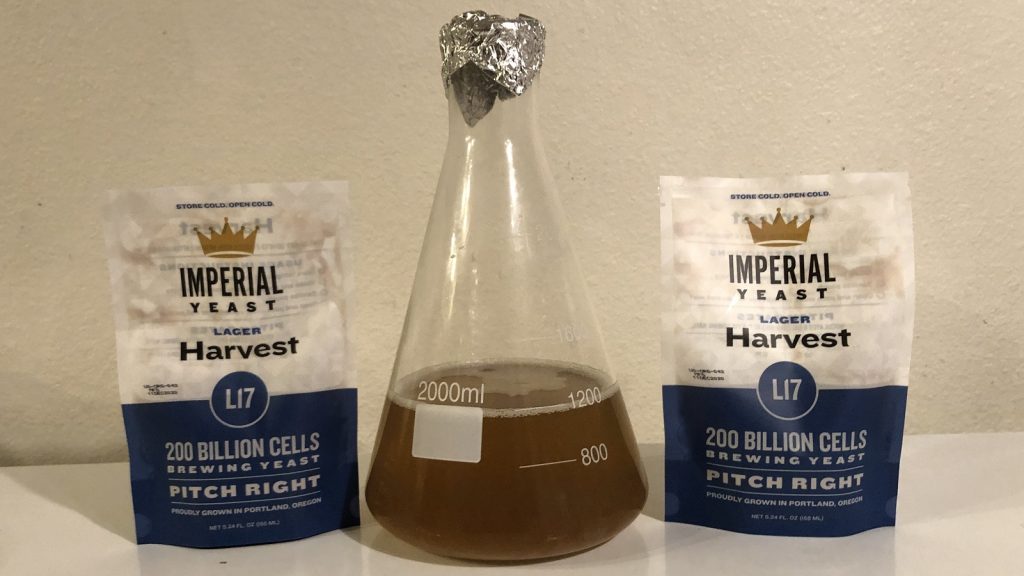

The filled carboys were placed in my chamber and left to finish chilling to my desired fermentation temperature, at which point I made a vitality starter with Imperial Yeast L17 Harvest.

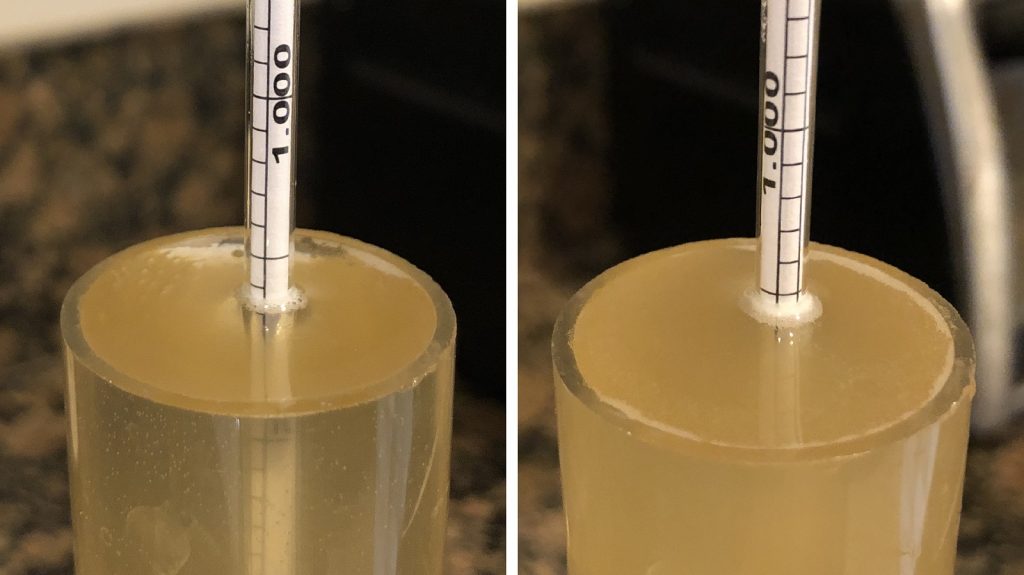

When the worts had stabilized at 59°F/15°C a few hours later, I split the starter evenly between them. After 5 days, I raised the temperature to 68°F/20°C and left the beers alone for 6 more days before reducing the temperature to 55°F/13°C. Hydrometer measurements taken 2 days later showed the beer made with flaked maize finished 0.001 FG lower than the one made with all barley malt.

At this point, I racked the beers to sanitized kegs.

The filled kegs were placed in my keezer and left on gas for 2 weeks before I began my evaluations, at which point I noticed a slight difference in appearance.

| RESULTS |

Due to social distancing practices as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic, data for this xBmt was unable to be collected in our typical manner. As such, temporary adaptations were made involving the author completing multiple semi-blind triangle tests in as unbiased a way as possible.

Utilizing 4 opaque cups of the same color where 2 were inconspicuously marked, one set was filled with the beer made without flaked maize while the other set was filled with the beer made with flaked maize. For each triangle test, 3 of the 4 cups were indiscriminately selected, thus randomizing which beer was the unique sample for each trial. Following each attempt, I noted whether I was correct in identifying the unique sample. Out of the 10 semi-blind triangle tests I completed, I needed to identify the unique sample at least 7 times (p<0.05) in order to reach statistical significance. In the end, I correctly identified the unique sample just 3 times (p=0.70), indicating my inability to reliably distinguish a Cream Ale made with all barley malt from one made with 20% flaked maize.

Despite looking different, these beers tasted identical to me, both possessing a pleasant grainy hay character with hints of spicy noble hops. I was happy to have a couple kegs of this refreshingly light Cream Ale on tap!

| DISCUSSION |

Using corn to make beer used to be highly frowned upon by craft beer aficionados, most of whom viewed its use as a cheap and flavorless means of boosting alcohol. Interestingly, it’s these very reasons that have caused many modern brewers to hold less harsh feelings about this adjunct, though concerns about negative flavor contribution persist. My inability to reliably distinguish a Cream Ale made with 21% flaked maize from one made with all barley malt indicates any impact was minimal enough as to be imperceptible.

While these results support the anecdotal claims of some, they contradict findings from a past xBmt where a panel of blind tasters were able to reliably tell apart a Pilsner made with 27% flaked maize from one made with all Pilsner malt. It’s possible the higher usage rate in that xBmt is what led to a perceptible difference, though 21% is a fairly decent amount as well. Moreover, it’s often said that the use of flaked maize leads to a thinner body and mouthfeel, yet I noticed no such characteristics either of these xBmt beers.

There are certain beer styles known for being made with a portion of corn, perhaps the most popular being Cream Ale, which I happen to enjoy quite a bit. While I couldn’t tell apart the beers in this xBmt, I will definitely continue using flaked maize when making Cream Ale as well as other styles. In addition to appreciating the lighter color contribution, there’s something satisfying to me about doing things the “old way,” whether it’s absolutely necessary or not.

If you have any thoughts about this xBmt, please do not hesitate to share in the comments section below!

Support Brülosophy In Style!

All designs are available in various colors and sizes on Amazon!

Follow Brülosophy on:

FACEBOOK | TWITTER | INSTAGRAM

If you enjoy this stuff and feel compelled to support Brulosophy.com, please check out the Support page for details on how you can very easily do so. Thanks!

13 thoughts on “exBEERiment | Impact The Use Of Flaked Maize Has On Cream Ale”

I brewed a 10% flaked maize “Brazilian Pilsen” and served along with an All Malt beer for 17 tasters. 10 out 17 correctly identified the odd beer, reaching statistical significance.

So I could say based in my experience and in the past xBeerperiment that most of the people would taste the diference for 10 and 27% flaked maize.. also I could risk saying that they probably would get 20% as well (if the world was completely linear, which it is not)…

…but if it does not make diference for YOU, it does not matter what others can taste or not, right? Specially during this quarantine – no sharing beer times ;).

Great Job, nice results. Thank you for posting.

Thanks for the information on your test. Unfortunately, it has led to confusion for me. While it seems to contradict what the article found @ 21% maize (albeit, from one tester) but seems to agree with the previous xBmt @ 27% maize. Your test involved 10% maize and reached statistical significance for distinguishing the different brews. It’s reasonable to think that the higher the maize proportion, then the easier it would be to distinguish it from an all malt beer. My confusion leads to wondering if brewing/testing protocol made a difference including the beer “glasses”, the grain bill, water, yeast, etc.? With the xBmt experiments, this information is listed. Anyway – thanks again.

Let’s try un-confuse then.

xBmt 1 – 27% flaked maize. 12 out of 23 participants got it right – significant

xBmt 2 – 21% (not 20% as I wrote) flaked maize, 1 participant, 3 out of 10 test got it right – non significant

My xBmt – 16% (not 10% as I thought it was) – sorry about that, I have some degree of dyslexia 🙂 – 10 out of 17 participants got it right – significant

My procedure is pretty much the same the guys use here. You can see all the results in the link above. It’s in Portuguese though, but google translator can help you 🙂

https://zoletando.medium.com/só-bebo-puro-malte-25984509af5d

(Any questions from the test please feel free, I will be glad to answer)

One other interesting result from my test: after we found the tests results reached statistical significance, not a single participant got it right that the variable was the use of corn. They identified a diference, but could not identify what was the diference. Then I revealed it was Corn. 8 out of 17 got it right which one was brewed with corn!

This amazes me because Corn nowadays is the 5th apocalypse knight when talking about beer in Brazil, pointed as the responsible for the bad quality from the mass produced beers (they can brew up to 45% adjuncts). My results (in my own free non scientific conclusion) is that the problem is the beer geeks, not the corn. That and the mass breweries that make bad beer at all. This last conclusion is reinforced by the fact that they are brewing some 0% adjuncts beer and the beer remains bad :).

Do you guys ever read “Shut Up About Barclay-Perkins” from Ronald Pattinson? He has the almost complete archives of 200 year British brewing history.

The reason I bring this up is that there is a tendency of people to think that sugars and corn are used to cheapen the brew. But that is only a rather recent historic consequence. Until the time between the wars, corn and sugar were more expensive for British brewers than using barley. And yet you see them used in the 19th century, in many kinds of beer recipes, sometimes with more expensive processes (like boiling maize grits).

Martyn Cornell and Roland Pattinson prove that many stories coming out of the US craft and homebrew community need to be taken bit very big grains of salt.

I’m sure that the reasons behind using adjuncts in the past were not based only in the “cheapen the brew” argument. There is a great podcast from experimental brewing exploring the history in the US. Amazes me the use of corn + 6row barley from the german immigrants.

But I can not agree that the “cheapen the brew” argument is “recent history”. It depends how many years we consider as recent and where the history is told.

Corn was (and still is) more cheap than Barley in Brazil. I could guess that in Mexico as well. Ok, we do not have a “traditional brewing school” like Germany, England, Belgium, etc.

But in Brazil it is still used to cheapen the brew (specially for the big mass producers like Ambev), despite the fact that this changing, specially because the local “craft” revolution.

In Fact, homebrewers had attached the Corn as the enemy of good beer and marketed that their “all malt” beer was better. This urban legend still persists and was so accepted by the local people that even Ambev and other giants are brewing “all malt” beers.

Most of their “all malt” beers are still not ok, helping me in my argument that is not the Corn that make bad beer, it’s the brewer. :). And shame on us, Brazilian home brewers, to spread this “Corn Enemy” non sense argument… 😉

Hey, Zolet, with “recent history” I actually mean after WWII. Then, these things became globally cheaper.

Like I pointed out (“Shut Up about Barclay Perkins” somewhere has the data), these things were more expensive in the past, and brewers still used them.

Got it Jurgen!

I am sure we can use WWII as reference in time for US and UK. And then you are very right, the cheapen argument is not be entirely right.

I made a little research in Brazilian history. What I found was that, similar to US, we had German immigrants coming to Brazil during 19th and 20th century. When they arrived here, there was no access to Barley.

First immigrants in the 19th century used corn (sometimes malted by themselves) besides rice. Not only because it was cheaper, but again, it was the only grains available. So down here it was always (in the past and in the recent times) cheaper using corn.

Then with time they started using barley (imported or local) and the recipes switched to malted barley, reaching up to 100%. After the WWII the big breweries copy-paste US light lagers, reintroducing corn and rice in the recipes. Hops/ IBUs also started to declined with time.

Local costumers did not complained (or even liked it?) and that’s our “Brazilian Pilsen” since then. By the law maximum adjuncts were allowed up to 45%.

So again, we can not say that it was globally expensive before WWII and the became globally cheaper after it. Down here it was always cheaper using Corn, even before WWI.

Jürgen is dead-on correct. The British used corn in many (most?) of their ales before and after WWII. Corn, occasionally rice, and invert sugars were ubiquitous in UK brewing. The no-adjuncts bias of American home and craft brewers is rooted in both a misguided application of Reinheitsgebot to American brews and the idea that adjuncts are used to “cheapen” the brewing process. Our reaction to thin, monotonous macro-beer was to up the malt and hops. That gave us some really great beers but those beers are not clones from some mythical pre-WWII beer nirvana. I think brewers are realizing this but it does not help that the BJCP has been slow to correct misinterpretation of historical brewing methods in its style guidelines.

I absolutely agree that the British were intentionally choosing flaked maize and sugars in addition to malt, and it’s interesting to see in the changes to grists that Pattinson documents from the 1930s to 1950s as brewers were trying to adapt to wartime supply issues.

I think the challenge for homebrewers is that it’s very possibly tied into mash, fermentation and casking issues which are hard to divine and hard to duplicate. His records can only go so far in documenting what they were doing, and a lot was lost, unfortunately.

At any rate, I can’t recommend his blog highly enough. His book on home brewing historical beers is great too. His writing style veers between highly technical on the one hand and cranky, funny, rowdy British observations on the other. It’s an amazing resource. It really drives home how rich the world of British beer history is.

I would say this is probably pretty unique to you. I can absolutely tell the difference in a beer that has over 20% corn. Corn is a completey different taste that barley malt.

It unfortunately showcases the limitations of a single taster. It’s not good nor bad (and my comment is nowhere meant to be close to a criticism) but people’s flavor thresholds are wildly different.

I also still like putting some flaked corn in a British mild ale or ESB. It adds a certain “more-ish” component versus an all malt beer of similar gravity. I just find them more crushable, but that’s my opinion.

I think I have to agree with about a little flaked corn in some English beers. My theory is that the corn add little more fermentability for the English yeast strains, thus finishing a bit dryer and possibly still leaving some malt sugars behind for flavor. Just a theory.

Andy, great work on the article. This is a style I have yet to brew but is on my short list for this summer. I have access to malted corn through a local maltster in Raleigh. Maybe an xBmt malted vs flaked corn???

Btw, do you think the IBU level maybe had something to due with your xBmt not being significant and Brian’s being significant? Maybe some interplay between the hops and the sugars during the boil/fermentation?