Author: Phil Rusher

Of the many sensory aspects pertaining to beer, among the most difficult for brewers to achieve are foam stability and mouthfeel. While certain parts of the brewing process are said to contribute to such characteristics, for example mash temperature, maltsters have developed a variety of products purported to enhance body and head, the most common being dextrine malts.

Generally speaking, dextrine malts are similar to crystal/caramel malt in that their starches are converted prior to being roasted thus ostensibly contribute little if any fermentable sugar while adding long-chain dextrins to wort. The exact process each maltster uses to produce their version of dextrin malt is proprietary, though all are believed to result in a more dextrine rich wort that should ultimately boost mouthfeel and foam retention in the finished beer without impacting flavor.

One of the more common dextrine malts is Carapils, which is produced by Briess Malting, and despite nearly every brewer I know swearing dextrine malt is key to producing beer with good body and head retention, I’ve largely omitted it from my recipes. Validating my decision is not only a past xBmt showing little difference between beers brewed with and without Carapils, but also research by Dr. Charlie Bamforth, aka the Pope Of Foam, suggests crystal malts including Carapils are in fact foam-negative. Curious to see for myself, I decided to put this variable to the test again.

| PURPOSE |

To evaluate the differences between a hoppy Pilsner made with dextrine malt and the same beer made without dextrine malt.

| METHODS |

In order to keep the variable in focus, I went with a German Pils recipe that had a very simple grain bill– one would be made with all Pilsner malt while the other would have 10% of the Pilsner malt replaced with Carapils, the maximum recommended by Briess. Given the previous Carapils xBmt was on a minimally hopped Blonde Ale, I went with something a bit more hop forward for this one.

Wayward Son

Recipe Details

| Batch Size | Boil Time | IBU | SRM | Est. OG | Est. FG | ABV |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5.5 gal | 60 min | 44.3 IBUs | 3.7 SRM | 1.052 | 1.012 | 5.2 % |

| Actuals | 1.052 | 1.008 | 5.8 % | |||

Fermentables

| Name | Amount | % |

|---|---|---|

| BEST Pilsen Malt (BESTMALZ) | 11 lbs | 89.8 |

| Carapils (Briess) | 1.25 lbs | 10.2 |

Hops

| Name | Amount | Time | Use | Form | Alpha % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Loral | 20 g | 60 min | Boil | Pellet | 10.5 |

| Tettnang (Tettnang Tettnager) | 30 g | 20 min | Boil | Pellet | 3.9 |

| Kohatu | 20 g | 20 min | Boil | Pellet | 5.2 |

| Tettnang (Tettnang Tettnager) | 40 g | 1 min | Boil | Pellet | 3.9 |

| Kohatu | 20 g | 1 min | Boil | Pellet | 5.2 |

| Kohatu | 40 g | 5 days | Dry Hop | Pellet | 5.2 |

| Tettnang (Tettnang Tettnager) | 40 g | 5 days | Dry Hop | Pellet | 3.9 |

Yeast

| Name | Lab | Attenuation | Temperature |

|---|---|---|---|

| Harvest (L17) | Imperial Yeast | 72% | 50°F - 60°F |

Notes

| Water Profile: Ca 50 | Mg 10 | Na 5 | SO4 105 | Cl 45 |

Download

| Download this recipe's BeerXML file |

After collecting the water for each batch and adjusting both to my desired profile, I weighed out and milled the two sets of grain.

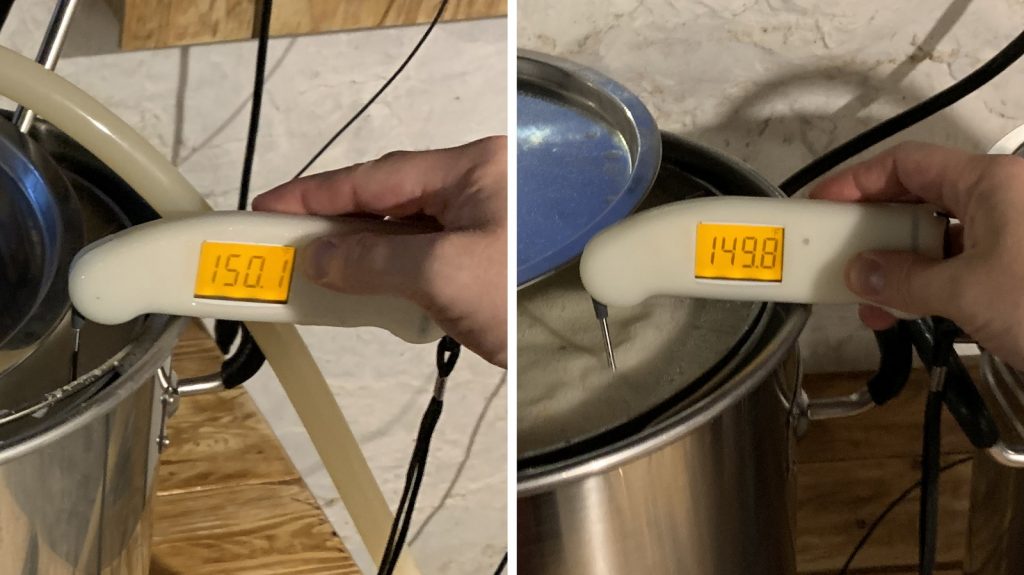

With the waters adequately heated, I incorporated the grains and checked to ensure they were at the same target mash temperature.

I then set each Clawhammer Supply controller to maintain the mash temperature and began recirculating the wort.

When each 60 minute mash rest was complete, I removed the grain baskets and let them drip into their respective kettles while heating the wort.

I then proceeded to measure out the kettle hop additions for both batches.

When the boils were finished, I chilled them with my CFC on their way to sanitized carboys.

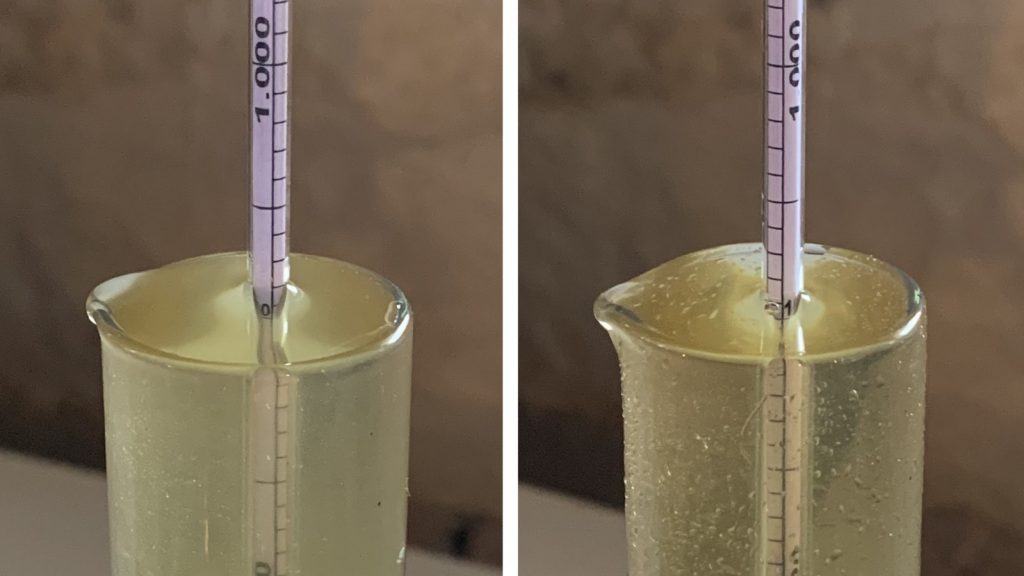

Refractometer readings showed the worts had indeed reached the same OG.

Using remnant wort from each batch, I made starters with Imperial Yeast L17 Harvest.

The following morning, with both worts stabilized at my desired fermentation temperature of 65˚F/18˚C, I pitched the yeast. Fermentation activity was noticed later that afternoon and continued for the following 4 days, at which point I raised the temperature to 68˚F/20˚C. After an additional 5 days, I took hydrometer measurements showing the beers reached nearly the same FG.

The beers were then racked to sanitized and CO2 purged kegs.

The filled kegs were placed in my keezer and pressurized with CO2. Because I wanted more hop aroma than what was present, I added a modest charge of hops to sanitized stainless steel canisters and place one in each keg. I then burst carbonated and left the beers to condition for about 2 weeks before I began my evaluations.

Once each glass was empty, it appeared lacing was similar for both.

Given claims Carapils helps with head formation retention, I documented the foam over the same period of time for each beer.

| RESULTS |

Due to social distancing practices as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic, data for this xBmt was unable to be collected in our typical manner. As such, temporary adaptations were made involving the author completing multiple semi-blind triangle tests in as unbiased a way as possible.

Utilizing 4 opaque cups of the same color where 2 were inconspicuously marked, one set was filled with the beer made without Carapils while the other set was filled with the beer made with 10% Carapils. For each triangle test, 3 of the 4 cups were indiscriminately selected, thus randomizing which beer was the unique sample for each trial. Following each attempt, I noted whether I was correct in identifying the unique sample. Out of the 10 semi-blind triangle tests I completed, I needed to identify the unique sample 7 times (p<0.05) in order to reach statistical significance, though I did so only 4 times (p=0.441), indicating my inability to reliably distinguish a hoppy Pilsner made with all Pilsner malt from one that included 10% Carapils in the grist.

These beers were exactly the same to my palate, with both having a very pleasant hop aroma and crackery pilsner malt flavor while I detected no differences in mouthfeel or head.

| DISCUSSION |

Carapils is billed as having negligible flavor and aroma impact while providing foam stability and body, which it purportedly does by contributing unfermentable long chain dextrins to wort. While my inability to reliably distinguish a hoppy Pilsner made with all Pilsner malt from one whose grist consisted of 10% Carapils indicates Carapils contributed no flavor or aroma, it also suggests it had little if any impact on body and mouthfeel.

These results corroborate those from a prior xBmt on Carapils, as well as a the findings from a past xBmt on another popular dextrin malt, adding more evidence to the idea these products may not have the impact they’re widely believed to. While a stern observer may notice slight differences in foam quality and lacing between the beers in this xBmt, it’s possible this is due to something other than the use of Carapils, and minor enough to be arguably negligible.

I had limited experience with Carapils prior to this xBmt and while I appreciated seeing its impact for myself, I have no plans to start using it regularly in my brewing. That said, having read that dextrin malts such as Carapils can actually be foam-negative, I’m compelled to point out that I personally observed no such impact in this xBmt, as the foam quality of these beers was nearly identical.

If you have any thoughts about this xBmt, please do not hesitate to share in the comments section below!

Support Brülosophy In Style!

All designs are available in various colors and sizes on Amazon!

Follow Brülosophy on:

FACEBOOK | TWITTER | INSTAGRAM

If you enjoy this stuff and feel compelled to support Brulosophy.com, please check out the Support page for details on how you can very easily do so. Thanks!

29 thoughts on “exBEERiment | Dextrin Malt: Impact Of Carapils On Hoppy Pilsner”

Great experiment, it once more goes to show that doctrin is not always reliable! One small thing, your water profile really accentuates dryness and hoppiness. What’s more, your BU/GU ratio is 0.85, very hop forward. Do you think this might have contributed to your inability in reliably distinguishing a beer brewed with carapils from one with a 100% pils malt grist? I would be interested in seeing if this still holds with, say, a less hoppy beer with a balanced water profile.

Right, part of the reason we did it this way was to see what would happen when we used a hop forward beer because in prior xbmts showed that tasters couldn’t detect differences in minimally or standard hopped beers. Moreover, the purported benefits of dextrine malt have nothing to do with anything except beer foam and mouthfeel. Taking that and all of our data points into consideration, I’d guess that the water profile and theoretical IBU do not have a substantial effect.

Doesn’t dry hopping help with head retention? Therefore reducing the effect of the variable?

These beers had a minimal dry hop charge to begin with. However, dry hopping effects on foam (among other things) is variable depending on which hop varieties are used. In this study linked below it appears that dry hopping tends to decrease foam stability of anything, but again, it is hop variety dependent and the ones I used were not studied here. It’s possible that the dry hop charge I used affected these beers, but it does not seem to be likely due to the small quantity.

https://www.mbaa.com/meetings/districtpresentations/DistrictPresentations/MAYE,%20Dry%20Hopping%20and%20its%20effects%20on%20bitterness%20the%20IBU%20test%20and%20beer%20foam.pdf

What do you think is required for good head retention? You seem to have no problem keeping a good head and lacing.but I can’t get that in my beers. I don’t like a big foamy head but I do like a fairly thin, stable head on my bottle conditioned English bitter ales. I currently have to add a little heading powder to the top of my beer and mix it at the surface after it’s poured out, to keep a satisfactory stable head that lasts down to the bottom of the glass. Like all cask and bottle conditioned English ales, my beers have low carbonation and don’t require chilling, other than to maybe a little below room temperature in the summer.

One thing is that my beers are quite low strength to the ones you brew. I aim for 3.5% to 4% alcohol, which is a strength very commonly found in English pubs for a basic session bitter. Maybe the low strength limits the degree of head retention.

I’ve tried all sorts of things to try to get a stable beer head. I’ve added wheat malt, torrefied wheat, rye malt, carapils or dextrin malts and various crystal malts to the mash to no avail. All wheat malt does is make the beer cloudy in my brews. Maybe my beers are not strong enough to develop and stable head without the help of some ethylene glycol arginate?

As with most situations, there’s no one thing that is responsible for good beer foam, and it appears that there are many things that affect foam quality. One thing that sticks out from what you’ve written here is that you are utilizing minimal carbonation methods in order to stay true to British styles, and carbonation can have big effects on beer foam. Another is that high alcohol content tends to be foam negative, so your 3-4% ABV beers should do pretty well in that regard. I’ve found in my experience that foam looks better when the beer has a higher terminal gravity, so using a higher mash temperature might help with that (this will also keep ABV down as well).

Another big factor that’s pretty easy to control for is having very clean glassware that is free of any residual soap/detergent residue. I always wash my glasses with regular dish soap but I also make sure to rinse them out very, very well with water that is as hot as my water heater will allow. Glassware with foam positive nucleation points can be helpful too.

It’s equally important to ensure that your brewing gear and any vessels used for conditioning (bottles, casks, kegs) are completely clean and free of any residuals from cleaning products.

I regularly brew session ales in the 2.8-3.2% range with plenty of foam on every pour. Once you’ve eliminated Phil points, play around with your mash temp. I typically mash session ales between 67-69°C depending on the grain bill. Mashing low gravity grain bills below 67°C would produce thin beer with little to no head.

Just anecdotally, I’ve made 4% abv beers using Simpsons MO only that get that stupid thick shaving cream kind of head (I actually hate that), but when I bottle condition I aim for 2.5 volumes. FWIW I always wash my glasses in the dishwasher and always use a rinse aid (Finish) and don’t have head retention issues.

https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/Positive-and-negative-impacts-of-specialty-malts-on-Combe-Ang/6e75507677765112d3c076d4de7ab6a779d950ff

Did you adjust the mash pH? If so, at what pH did you plan to mash?

I use Bru’n Water for any mash additions but I don’t focus too much on pH if I’m honest. As long as the spreadsheet tells me the pH is between 5.3 and 5.5 I usually just let it ride without making further adjustments with acid. Here though, I did add some acid to both mashes for a theoretical pH of about 5.4, though I did not measure it.

Regarding mouthfeel Palmer says that both the final gravity and the pH affect the mouthfeel of beer, and I tend to agree. I did a hazy ale that I mashed at a temperature higer than expected due to a broken thermometer and got a FG of 1016, but fermented it with a kveik yeast that resulted in a final pH fo 4.2: that beer had a very thin body.

Did the same recipe with a proper mash temperature and raised the pH at boil to 5.8 and got a FG of 1.013 and a final pH of 4.6. That beer had a great mouthfeel, very different from the first one.

Carapils and dextrine malts increase the FG a point maybe, but that alone won’t give you a noticeable difference in mouthfeel. You need to combine this with pH and maybe other malts that also increase the FG in order to achieve a noticeable difference in my opinion.

One beer had 11# Pilsner and 1.25# Carapils. The other had 12.25# Pilsner but they both had the same OG? Or did they both have 11# Pilsner and one had the Carapils added? Thanks

The experimental beer with Carapils had 11 pounds of Pilsner malt with 1 pound and 3.5 ounces of Carapils. The control beer had only 12 pounds of Pilsner malt. I used different masses of malt in order to account for any differences in OG while allowing for the experimental beer to have 10% Carapils.

Do you think these hops would work well or be worth trying for a similar beer?

warrior 60 min

centennial/cascade 20

centennial/cascade 1

Right at about 45 IBU

Harvest yeast

I have lots of hops to burn through.

Thanks for your time!

Totally. Sounds like an excellent IPL recipe.

I’ve heard it suggested that dextrin malts should not have much of an impact on body or head retention unless you’re employing a multi-rest mash with a highly modified base malt. That leads me to believe there should be little to no difference when employing a single infusion mash at a temperature that is balanced between both alpha & beta amylase. I would love to see an exbeeriment or even do one myself brewing a Belgian Golden Strong Ale with protein, beta & alpha amylase rests using nothing but pilsner base malt & table sugar for fermentables vs the same recipe with 10% of the base malt replaced by dextrin malt!

I’ve heard it suggested that dextrin malts should not have much of an impact on body or head retention unless you’re employing a multi-rest mash with a highly modified base malt. That leads me to believe there should be little to no difference when employing a single infusion mash at a temperature that is balanced between both alpha & beta amylase. I would love to see an exbeeriment or even do one myself brewing a Belgian Golden Strong Ale with protein, beta & alpha amylase rests using nothing but pilsner base malt & table sugar for fermentables vs the same recipe with 10% of the base malt replaced by dextrin malt!

I’ve been wondering whether cara-pils might help sour beers with head retention. Lately I’ve been trying out playing with mash temps and souring just 1/2 the batch to improve head with so-so success. I don’t use cara-pils much anymore between the results of some exbeeriments here and Palmer’s suggestion that it may be responsible for an excess of digestive upset (shall we call it?). Maybe cara-pils is the answer?

@Chrisgg: I would agree that there is no reason lower alcohol beers should lack head. I’ve been brewing a fair number of 3.5% lagers of late and head is no issue. Carbonation may be an issue though. Try running your British cask ale style through a stout faucet perhaps?

If you take into account the amount of maltodextrin one needs to add to a beer before one will notice it the 10% of the grist of carapils is nothing, and the result is not surprising. Carapils as a bodybuilder in beer is just one of the ingredients and techniques one may use. And normally one will use more then one, and hope that the ingredients and techniques will result in a greater body than the sum of its parts (that is that they have a cumulative effect).

I have always wondered why carapils is added in the mash. If one was looking to add long chain dextrins in finished beer, why would anyone expect to have these survive when exposing the dextrins to the high enzyme content in a mash or 60 minutes or more? To me this would be a great place for “mash capping” during a sparge, or add really late for a full volume mash. Please let me know if I missed anything. For my beers, I don’t use the malt and typically mash a bit warmer to get the effects I desire.

Therein lies the rub. There are four major enzymes present in malted barley (alpha amylase, beta amylase, alpha glucosidase, and limit dextrinase), and each of them functions differently with their own “preferences” for hydrolysis. The one that’s responsible for the cleavage of amylopectin is limit dextrinase, and it is really only active at a particular temperature range that is lower than typical mashing temperatures. So assuming that it is true that dextrin malt contributes unfermentable dextrins to wort, you would need to mash at lower than standard temperature while increasing the availability of protons (decrease pH) in order for limit dextrinase to effectively cleave long chain polymers.

I love seeing carapils put to the test! I’ve also never been a fan, although maybe that is because of the Bamforth paper. I feel like Weyermen Carafoam does have an impact on body and foam and use it a fair amount, but maybe that’s just “feelings”. 🙂

Can’t blame you for getting the feels sometimes! I haven’t used Carafoam but I recently got some Carahell to try out for S’s and G’s. Looking forward to seeing what happens!

Dan, I feel the same way about carafoam. I’ve heard it’s the Weyermann’s version of chit malt. Again, I’ve heard this is different than carapils thus creating a difference in body and fermentability. I can neither confirm nor deny this, just word of mouth and feelings 😜

I thought the idea of carapils was to use it when head retention was going to “need help”.. like when using an adjunct like coconut that typically thins the beer… or a grain bill that might be light on base malts?

Maybe. But if that’s the case then it shouldn’t matter if it has foam positive effects. It’s not like the malt will only allow for benefits when there are lipids in the wort or something.

Echoing what has more or less already been said, but I think its important because “dextrin malt” can significantly decrease wort fermentability, you had a very long mash at a pretty low mash temp. I bet if you mashed for 30 minutes at something like 154 or 155 you’d see a bigger difference. But this was a cool experiment either way. As were your previous experiments at higher mash temps. In my experience, mash duration is as important as temperature for determining wort fermentability. Also, again echoing previous comments, foam will probably not be different between an all-malt mash and an all-malt mash +10% carapils.

I don’t think anyone would say an hour long mash is very long. In fact, it’s the gold standard as far as mash times go. 150F is also fairly standard for producing fermentable wort, much like you say. However, limit dextrinase is the only enzyme capable of cleaving the dextrinous bonds that are said to be imparted from dextrin malt such as Carapils, and limit dextrinase is only active at lower temperatures than what I used here. Its activity also benefits from low mash pH, which is not something that I aimed for here.