Author: Jake Huolihan

Chilling fermented beer prior to packaging is a step many brewers employ as a means of forcing unwanted particulate matter out of solution, which in addition to reducing the risk of clogs, is widely believed to improve clarity. As simple as this method seems, there are a few things concerned brewers consider when cold crashing, one of which involves the yeast placed on stress during the chilling process.

As the microorganism responsible for converting wort into beer, it’s prudent to ensure the fermentation environment is as hospitable to yeast as possible in order to avoid undesirable off-flavors. It’s well established that rapid temperature changes can cause yeast to experience a heat shock response that can lead to the release of undesirable flavor compounds. For this reason, many brewers espouse a slow and steady approach to cold crashing where the temperature of the beer is gradually reduced over time.

Yeast being a living organism that’s known to produce various perceptible compounds like esters and phenols, it always made sense to me that the stress of rapid cooling could be problematic. Even after the results from a past xBmt showed tasters couldn’t tell apart a Helles cold crashed quickly from one chilled gradually, I couldn’t help but wonder if this was something that mattered and would often worry when reducing the temperature quicker than usual. Unable to collect data due to COVID-19, I decided to test this variable out again on a cool fermented German Pils.

| PURPOSE |

To evaluate the differences between a German Pils that was cold crashed rapidly and one that was cold crashed gradually over time.

| METHODS |

Wanting any impact of the variable to be as easy to detect as possible, I went with a simple German Pils recipe for this xBmt.

Perennial

Recipe Details

| Batch Size | Boil Time | IBU | SRM | Est. OG | Est. FG | ABV |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5.5 gal | 30 min | 34.6 IBUs | 4.3 SRM | 1.053 | 1.012 | 5.3 % |

| Actuals | 1.053 | 1.012 | 5.4 % | |||

Fermentables

| Name | Amount | % |

|---|---|---|

| Odyssey Pilsner | 12 lbs | 97.66 |

| Melanoidin (Weyermann) | 3 oz | 1.53 |

| Munich II (Weyermann) | 1.6 oz | 0.81 |

Hops

| Name | Amount | Time | Use | Form | Alpha % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nugget | 25 g | 30 min | Boil | Pellet | 13 |

| Tettnang | 33 g | 15 min | Boil | Pellet | 4.5 |

Yeast

| Name | Lab | Attenuation | Temperature |

|---|---|---|---|

| Harvest (L17) | Imperial Yeast | 72% | 50°F - 60°F |

Notes

| Water Profile: Ca 61 | Mg 0 | Na 8 | SO4 75 | Cl 55 |

Download

| Download this recipe's BeerXML file |

I started my brew day off by making a vitality starter with two pouches of Imperial Yeast L17 Harvest.

With the starter spinning, I collected the water, adjusted it to my desired profile, then weighed out and milled the grain.

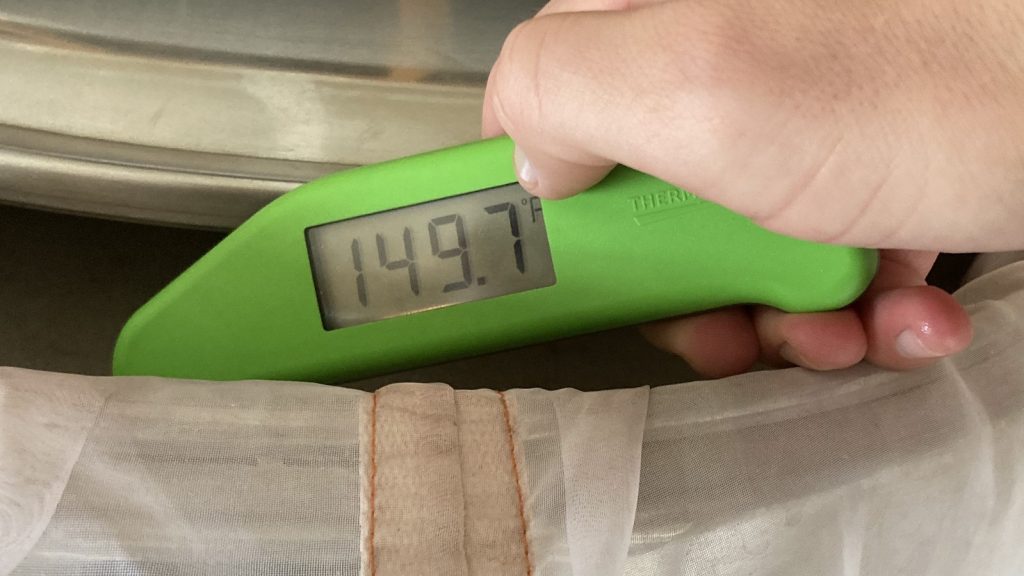

When the water properly heated, I incorporated the grains then checked to ensure it was at my target mash temperature.

The mash was left alone for 60 minutes.

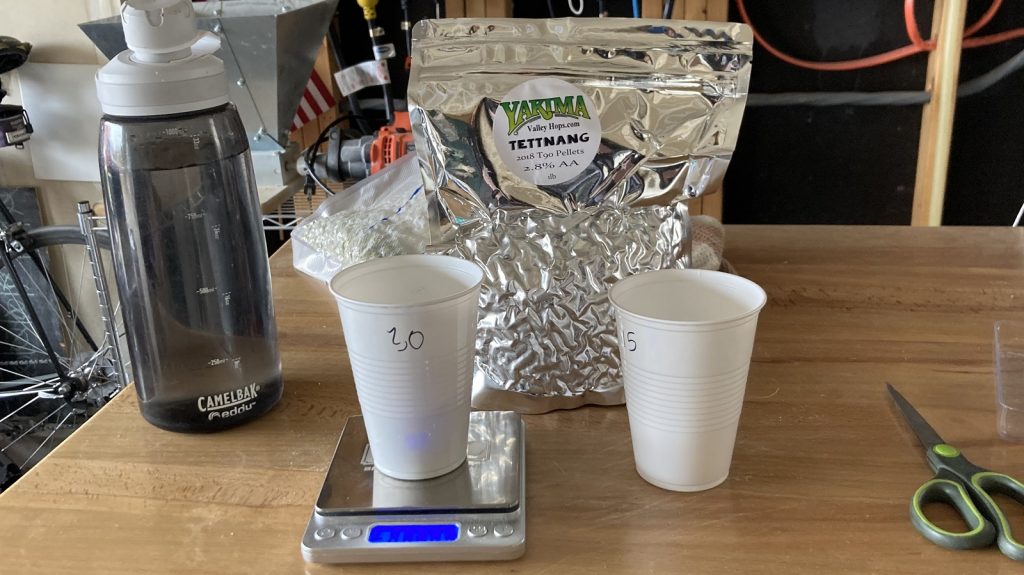

During the mash rest, I weighed out the kettle hop additions.

With the mash rest complete, I collected the sweet wort in my kettle and boiled it for 60 minutes with hops added as stated in the recipe.

Once the boil was complete, I quickly chilled the wort.

A refractometer reading showed the wort was right at the expected OG.

Identical volumes of wort were then racked to separate sanitized Unitanks.

The filled vessels were connected to my glycol rig and left for 15 minutes to finish chilling to my desired fermentation temperature of 52°F/11°C, at which point I split the yeast starter between them. After 4 days of active fermentation, I began gently raising the temperature of the beers until they reached 62°F/17°C then capped the Unitanks to allow a small amount of pressure to build up in order to prevent oxygen ingress when cold crashing. After 4 more days, with hydrometer measurements showing both beers were at the same 1.012 FG, it was time to introduce the variable. I set the controller for one Unitank to 40°F/4°C, which given my use of glycol, resulted in the beer dropping to temperature in less than 1 hour, while the temperature of the other beer was reduced by 2°F/1°C every 12 hours over 5 days until it reached 40°F/4°C. After letting both beers sit at the same temperature for an additional day, they were pressure transferred to CO2 purged kegs.

The filled kegs were placed in my keezer, burst carbonated, then allowed to condition for 2 weeks before being evaluated.

| RESULTS |

Due to social distancing practices as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic, data for this xBmt was unable to be collected in our typical manner. As such, temporary adaptations were made involving the author completing multiple semi-blind triangle tests in as unbiased a way as possible.

Utilizing 4 opaque cups of the same color where 2 were inconspicuously marked, one set was filled with the beer cold crashed rapidly while the other set was filled with the beer cold crashed gradually. For each triangle test, 3 of the 4 cups were indiscriminately selected, thus randomizing which beer was the unique sample for each trial. Following each attempt, I noted whether I was correct in identifying the unique sample. Out of the 10 semi-blind triangle tests I completed, I needed to identify the unique sample at least 7 times (p<0.05) in order to reach statistical significance. In the end, I correctly identified the unique sample just 3 times (p=0.70), indicating my inability to reliably distinguish a German Pils that was cold crashed rapidly from one that was cold crashed gradually over time.

To my palate, there was absolutely nothing different about these beers, they looked, smelled, and tasted identical. Good thing, because I really enjoyed drinking this German Pils! Clean, bready malt character with a pleasant bitterness and killer noble hop character.

| DISCUSSION |

Cold crashing is a method used by many brewers as a matter of course, the goal being to force as much particulate matter out of solution as possible prior to packaging. A common concern when employing this technique has to do with the stress placed on yeast during the cooling process, hence the recommendation to gradually reduce the temperature over time rather than rapidly chilling the beer. My inability to reliably distinguish a German Pils that was rapidly cold crashed from one that was cold crash slowly over multiple days suggests cold crashing speed had little perceptible impact.

Yeasts are living organisms that we know respond to their environment by excreting certain compounds, so the idea that quick and drastic changes in temperature would cause enough stress to lead to off-flavors isn’t implausible. Seeing as the results of this xBmt corroborate those from a prior xBmt, it seems batch size may be at play, as the pressures on yeast in commercial breweries are quite a bit more than smaller homebreweries.

I control fermentation temperatures using a glycol rig, which is remarkably faster at chilling than anything I’ve used in the past– what used to take many hours in my chest freezer fermentation chamber takes just minutes with glycol. Initially concerning when it came to cold crashing, these results have led me to question the existing dogma regarding speed, to the point I’m comfortable reducing the temperature of my beer as quickly as I can.

If you have any thoughts about this xBmt, please do not hesitate to share in the comments section below!

Support Brülosophy In Style!

All designs are available in various colors and sizes on Amazon!

Follow Brülosophy on:

FACEBOOK | TWITTER | INSTAGRAM

If you enjoy this stuff and feel compelled to support Brulosophy.com, please check out the Support page for details on how you can very easily do so. Thanks!

14 thoughts on “exBEERiment | Cold Crashing Speed: Immediate vs. Gradual In A German Pils”

We have always chosen the rapid chill method, which takes a few hours in our fermentation chamber. The results are always good. However, we do use gelatin fining to completely clear our beers. In the past, we relied upon extended aging for clarity.

The results of this may not be generalizable to other yeast. It is quite possible that this yeast is more resistant to cold stress than others. Each yeast would need a similar exBEERiment of it’s own to establish it’s response to cold stress.

I wonder how cold crashing speed affects the viability of reusing the yeast? That sounds like a tedious experiment.

I recall an advantage of slow crashing is for the health of the yeast when harvesting it for future batches.

Excellent study. Thanks for sharing! I remember reading somewhere that the advantage of slowly dropping to lagering temp is that the yeast isn’t shocked and more effectively continues to clean up the beer during lagering. Perhaps an extended lagering period would show this advantage of slowly dropping the temp.

Which glycol chiller do you use and do you recommend it?

I have a discontinued SS glycol chiller. I would highly recommend it if it was still being produced, it is fantastic.

Thanks for this excellent report.

I was wondering if you considered clarity?

The samples appear diffrent.

Is the slow chilled sample clearer?

I experimented once a yeast going berserk on a fast cold crash (don’t remember which one though) and since then, I find it is just not worth the risk to save what, 24h ?

What about my poor yeast cultures? I am effectively cold crashing them every time I put them back in the fridge after growing them up in fresh starter 🙂

I’ve often wondered that same thing about cold crashing my yeast starters. I’ve always read that I shouldn’t worry about off flavors generated in a yeast starter but what about the health of my yeast? I usually do 17 gallon batches & always do 2 steps when making a starter over the course of a week to make sure my inoculation rate is between 25-100 million cells per ml. Seems like no matter how I do a starter I’m going to have to do at least one thing that’s not recommended by either growing too many cells too fast or crashing too fast unless I want to spend at least 2 weeks growing yeast before I brew. :-/

I just brewed a German Pils with 34/70 and was it tasting great after the D-rest (no off flavours); I rapidly cold crashed and bottled it 3 days later. Noticed a sulfer/yeasty flavour and smell. My wife thought she tasted Diacetyl.

Anyone had this kind of issue with 34/70? maybe I disturbed the yeast cake while racking and that was the flavour? Hopefully it clears up while bottle conditioning…

Thanks for all the great info on this site!

I’m just crashing a Rice lager with the same yeast, did you use 2 packs out of interest?I fermented at 12C for 5 days before ramping up to 18C for another 7 day to be sure finished at 1.013

I’ll be kegging most but will bottle maybe 5 or 6.

I’ll let you know when I’m ready to drink.

Cheers, David.

If you are thinking of reusing yeast, the quick cold crash will harm the health of the cells. This test to be complete you should reuse the yeast where it was made slow cooling and where it was made fast cooling, then you would see the consequences of the cold crash.