Author: Marshall Schott

As children in grammar school are taught, the human tongue has five primary taste receptors for saltiness, sweetness, sourness, savoriness (umami), and bitterness. In cooking, certain ingredients are employed to ensure desired levels of each of these characteristics, which is also the  case when it comes to beer. When malted grains are mashed, the resultant liquid is called sweet wort, and while this could be boiled and fermented on its own, the end product would be overly sweet and unsatisfying.

case when it comes to beer. When malted grains are mashed, the resultant liquid is called sweet wort, and while this could be boiled and fermented on its own, the end product would be overly sweet and unsatisfying.

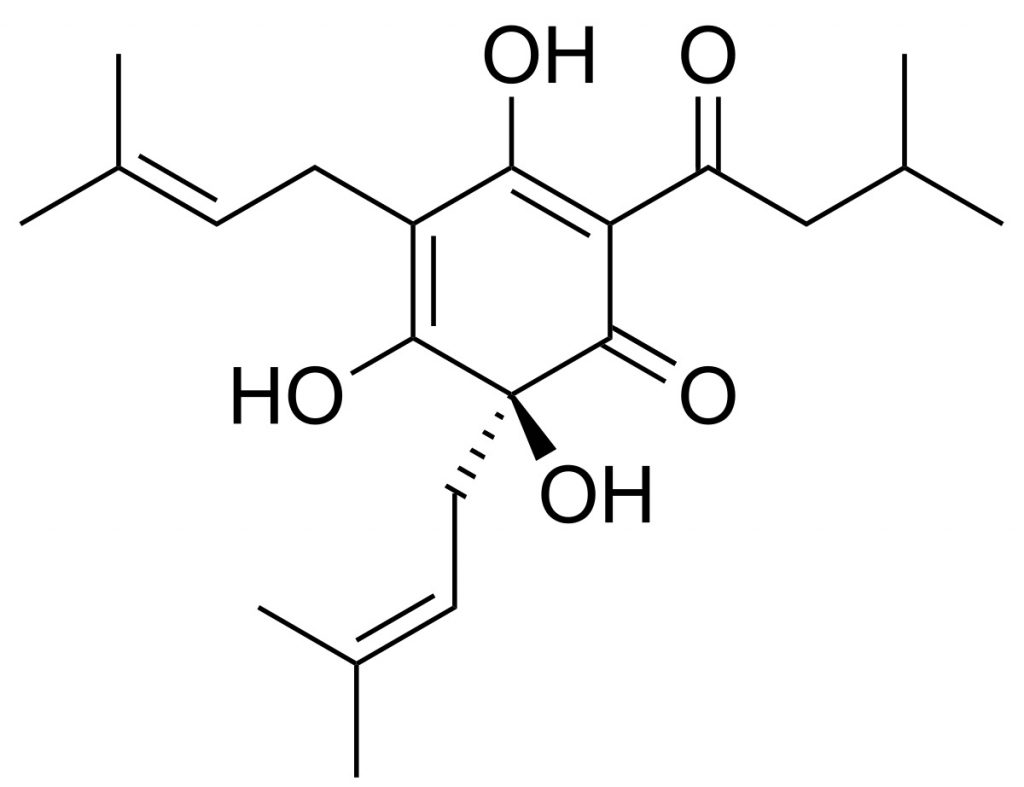

The primary ingredient brewers use to counter the sweetness imparted by malt is hops, which possess ample amounts of alpha acids (AA) that, when added to boiling wort, are isomerized into bitter iso-alpha-acids. It’s well established that the perceptible level of bitterness in a beer is correlated with the amount of time hops are in contact with the boiling wort, hence the oft repeated concept of a “bittering addition” referring those hops added at the beginning of the boil.

Modern advancements in and access to technology has made predicting bitterness levels in beer quite easy– using BeerSmith, I determine all of my early kettle additions based on the expected IBU rather than hop amount. However, as necessary as bitterness is in beer, too much can result in something that’s painfully unpalatable. Many moons ago, I brewed a Pale Ale recipe I found online but subbed in 12% AA Chinook for 5% AA Cascade at the same rate. Needless to say, I learned my lesson and now understand how bitterness can be either friend or foe.

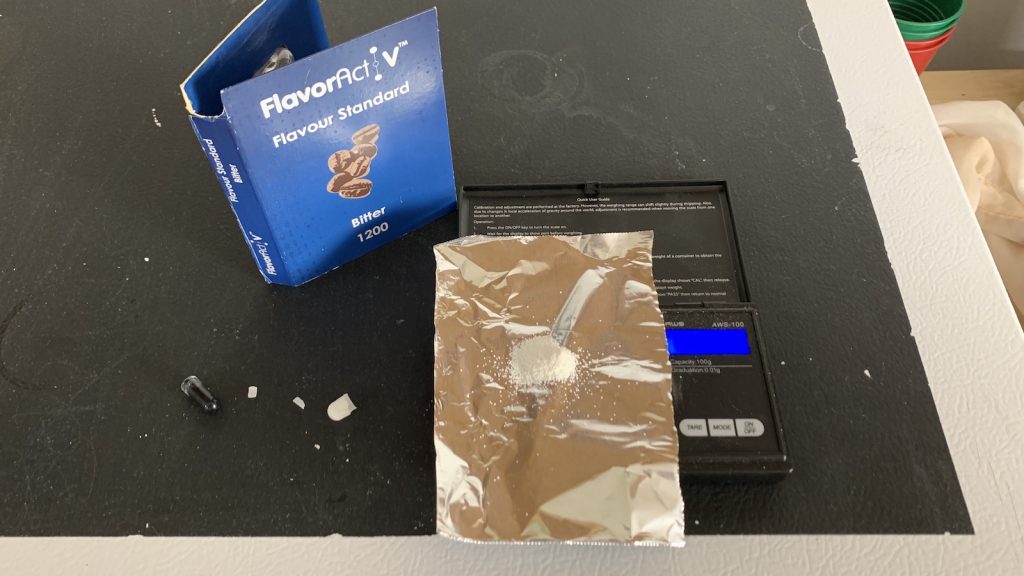

For this edition of our off-flavor series, FlavorActiV provided us with their bitter flavor standard, which is a concentrated form of iso-alpha-acids.

| PURPOSE |

To evaluate the differences between a pale lager dosed with bitter flavor standard and an non-dosed version of the same beer.

| METHODS |

Wanting to ensure any impact of the flavor standard wasn’t muddied by other characteristics, my beer of choice for this xBmt was the clean, crisp, and endlessly crushable Miller Lite. In addition to having a bunch on hand, making this an easy choice, my experience with Miller Lite is that it’s really not very bitter at all, which I figured would help to accentuate any impact of the flavor standard.

It’s commonly believed that differences of 5 international bitterness units (IBU) is around the point of perception for most people. FlavorActiV provided me with 5 bitter flavor standard capsules, each one said to achieve 3 times the flavor threshold when added to 1 liter of beer. Little information was provided as to what exactly this means when it comes to their bitter flavor standard, though FlavorActiV provides the following:

This Bitter GMP Flavour Standard imparts bitterness based on iso-alpha acids – from hops and hop oil extracts. Bitterness can also be imparted by other flavour types.

I reached out to FlavorActiV to ask how adding 1 capsule of bitter flavor standard to 1 liter of Miller Lite would affect IBU. Unfortunately, it was over the weekend prior to this article being published, hence I didn’t hear back in time. As such, I assumed it would contribute approximately 15 IBU given the previously mentioned 5 IBU perception threshold and FlavorActiV’s claim that each capsule achieves 3 times the flavor threshold. With this in mind, I weighed out the contents of a single capsule of the bitter flavor standard with plans to add 1/3 to a liter of Miller Lite in order to achieve a presumed increase of just 5 IBU.

I followed the instructions provided by FlavorActiV by first gently pouring about 200 mL of beer into a clean Nalgene bottle, adding the pre-measured flavor standard, gently swirling, then adding an additional 800 mL of beer to the vessel. I went through the same steps with the non-dosed sample to ensure similar levels of carbonation. With the powder fully dissolved, the beers were ready for evaluation.

| RESULTS |

Due to social distancing practices as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic, data for this xBmt was unable to be collected in our typical manner. As such, temporary adaptations were made involving the author completing multiple semi-blind triangle tests in as unbiased a way as possible.

Utilizing 4 opaque cups of the same color where 2 were inconspicuously marked, one set was filled with the beer dosed with bitter flavor standard while the other set was filled with the non-dosed beer. For each triangle test, 3 of the 4 cups were indiscriminately selected, thus randomizing which beer was the unique sample for each trial. Following each attempt, I noted whether I was correct in identifying the unique sample. Out of the 10 semi-blind triangle tests I completed, I needed to identify the unique sample 7 times (p<0.02) in order to reach statistical significance. In the end, I chose the unique sample 8 times (p=0.003), indicating my ability to reliably distinguish a Miller Lite dosed with bitter flavor standard from a non-dosed sample of the same beer.

| DISCUSSION |

Bitterness is necessary in nearly all beer styles as a means of balancing the sweetness derived from malt. This is achieved by adding hops to boiling wort, which results in the isomerization of alpha acids into bitter iso-alpha-acids, and bitterness level is a function of a particular hop’s starting alpha acid level as well as the time it spends in the boiling wort. While different styles range in their bitterness level, it’s commonly said that differences of 5 IBU are perceptible, which is supported by the fact I was able to reliably distinguish a Miller Lite dosed with enough bitter flavor standard to add approximately 5 IBU from a non-dosed version of the same beer.

It may be unsurprising to some that adding a physical substance to beer led to it being perceptibly different than a non-dosed beer, which is understandable. However, I thought it was rather confirmatory that I was able to tell beers apart that had just a 5 IBU difference. In my own brewing, I always rely on IBU for early kettle additions though use weight for any hop additions that come after the 30 minute mark. These results have definitely caused to rethink this approach, as even a smaller charge of a modern high alpha hop toward the end of the boil could contribute 5 or more IBU to the beer.

All in all, I found this to be yet another eye opening experience that I feel will assist in my ability to more effectively evaluate beer. For anyone who’s interested in honing their palate and improving their evaluation skills while also having some fun, I can’t recommend using flavor standards enough.

If you have any thoughts about this xBmt, please do not hesitate to share in the comments section below!

Support Brülosophy In Style!

All designs are available in various colors and sizes on Amazon!

Follow Brülosophy on:

FACEBOOK | TWITTER | INSTAGRAM

If you enjoy this stuff and feel compelled to support Brulosophy.com, please check out the Support page for details on how you can very easily do so. Thanks!

8 thoughts on “exBEERiment | FlavorActiV Off-Flavor Series: Bitterness”

So what this proves is Miller Lite needs to step on the gas a little bit more when it comes to their IBU’s…lol. This was interesting. I’ve come to find I don’t necessarily enjoy getting all my bitterness from a 30 minute or less addition. This probably has a lot to do with which hop is used or the style of beer I’m making. I like to get a majority of the bitterness from an early addition but, of course, I still play around with hop timing.

I realize my comment wasn’t very clear. This experiment made me think about the quality of bitterness in a beer. Seems like the flavoractiv added bitterness but maybe not a quality bitterness. This is something I’ve noticed with getting all of a beers bitterness from a late hop addition. Just one opinion.

Marshall,

While I agree that predicting the *input* IBUs to a beer is relatively easy, I think predicting the final IBUs is one of the biggest crapshoots in homebrewing, considering losses to hot and cold break, yeast, etc. and uncertainties in extraction for whirlpool/steeping additions. This is why I have always been surprised that most published clone recipes specify hop additions that yield predicted IBU levels that match those posted for the (finished) beer by commercial breweries, and that homebrew recipes seldom seem to account for these losses, either.

I’ve opined about this before, including some discussion with commercial breweries about how (or if) they account for IBU losses during fermentation (link reposted from the original discussion on the AHA website):

https://brewsreport.blogspot.com/2016/08/bitter-debate-two-perspectives-on.html

Interesting to learn that perception level is only 5 ibu or possibly less. This could explain why I’ve had some misses on non dry hoped beers lately. I’ve aimed for low 20’s but hit somewhere closer to 30.. great in my opinion but “too bitter” for some friends. Gonna have to dial beersmith in a little more to account for some boil variables happening in my oldschool setup. Possibly late boil editions are isomerizing more due to slow chilling. Something I need to account for.

Thanks for the great experiment and article!

Cool experiment. Would be nice to see repeat in something with some background bitterness. Maybe see if you can pick out +10 IBU to Sierra Nevada Pale Ale (38 IBU per the mfg website).

Agee. Marshall if you have some FlavorAct left over perhaps you could give it a try with Sierra Nevada or something similar and post what you find here in the comments. Thanks!

Do you know what the IBU of Miller LIte is?

And for your next experiment can you run a multi-point standard curve and demonstrate/disprove the idea that IBU perception saturates at some point?

I believe it’s 12 IBU