Author: Jake Huolihan

There’s little argument in the brewing world that oxygen is the enemy of beer freshness, but while much of the attention is focused on exposure that occurs after fermentation, some believe vectors for oxidation exist even earlier in the process. In the case of hoppy IPA, there’s been increased focus on the ingress that occurs at dry hopping, a practice that typically involves opening the fermenter to add a charge of hops that have often spent some time in the ambient environment.

Brewers have recently come up with a range of clever tricks for reducing oxygen exposure at the point of dry hopping, some more complicated than others. One rather simple method involves flushing the dry hop charge with CO2 just before adding it to the beer, the idea being that the inert gas will displace most if not all oxygen present in the hops, thus reducing the risk of oxidation down the line.

The first I heard of the idea of flushing dry hops with CO2 prior to adding them to beer was from a prior xBmt by Greg Foster. Given the apparent sensitivity of certain hoppy styles, this seemed like a good way to ensure the beer was exposed to less oxygen. I don’t dry hop very often, so curious of the impact this method might have, I put it to the test on a recent batch of IPA.

| PURPOSE |

To evaluate the differences between an IPA where the dry hop addition was either flushed with CO2 prior to being added to the beer or added without being flushed with CO2.

| METHODS |

For this xBmt, I designed a fairly simple IPA with a moderate dry hop charge.

Riddle Me This

Recipe Details

| Batch Size | Boil Time | IBU | SRM | Est. OG | Est. FG | ABV |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5.5 gal | 60 min | 134.7 IBUs | 8.1 SRM | 1.068 | 1.013 | 7.4 % |

| Actuals | 1.068 | 1.01 | 7.7 % | |||

Fermentables

| Name | Amount | % |

|---|---|---|

| Pale Malt - 2 Row (Cargill) | 12.5 lbs | 83.33 |

| Carahell | 1 lbs | 6.67 |

| Crystal, Medium (Simpsons) | 6 oz | 2.5 |

| Sugar, Table (Sucrose) | 1.125 lbs | 7.5 |

Hops

| Name | Amount | Time | Use | Form | Alpha % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Magnum | 50 g | 60 min | Boil | Pellet | 12.2 |

| Citra | 30 g | 45 min | Boil | Pellet | 12 |

| Mosaic (HBC 369) | 30 g | 30 min | Boil | Pellet | 12.3 |

| Citra | 30 g | 0 min | Boil | Pellet | 12 |

| Mosaic (HBC 369) | 30 g | 0 min | Boil | Pellet | 12.3 |

| HBC 438 | 22 g | 0 min | Boil | Pellet | 13.1 |

| Citra | 45 g | 7 days | Dry Hop | Pellet | 12 |

| Cryo - Mosaic | 45 g | 7 days | Dry Hop | Pellet | 22 |

| HBC 438 | 45 g | 7 days | Dry Hop | Pellet | 13.1 |

Yeast

| Name | Lab | Attenuation | Temperature |

|---|---|---|---|

| Voyager (A05) | Imperial Yeast | 70% | 64°F - 74°F |

Notes

| Water Profile: Ca 50 | Mg 0 | Na 8 | SO4 75 | Cl 36 |

Download

| Download this recipe's BeerXML file |

I started my brew day by collected the full volume of water for an 11 gallon/42 liter batch then heating it up with my heat stick.

I then weighed out and milled the grain.

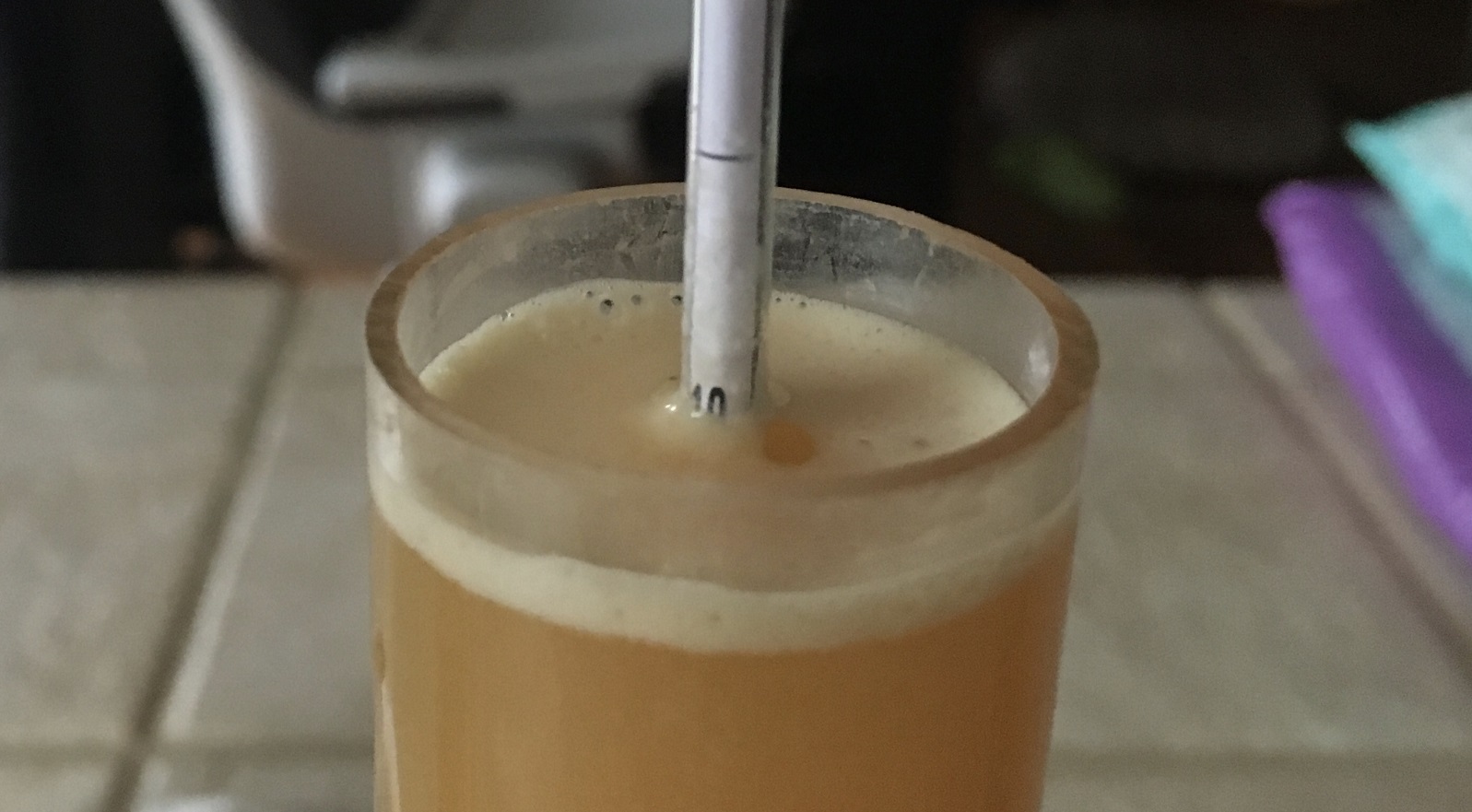

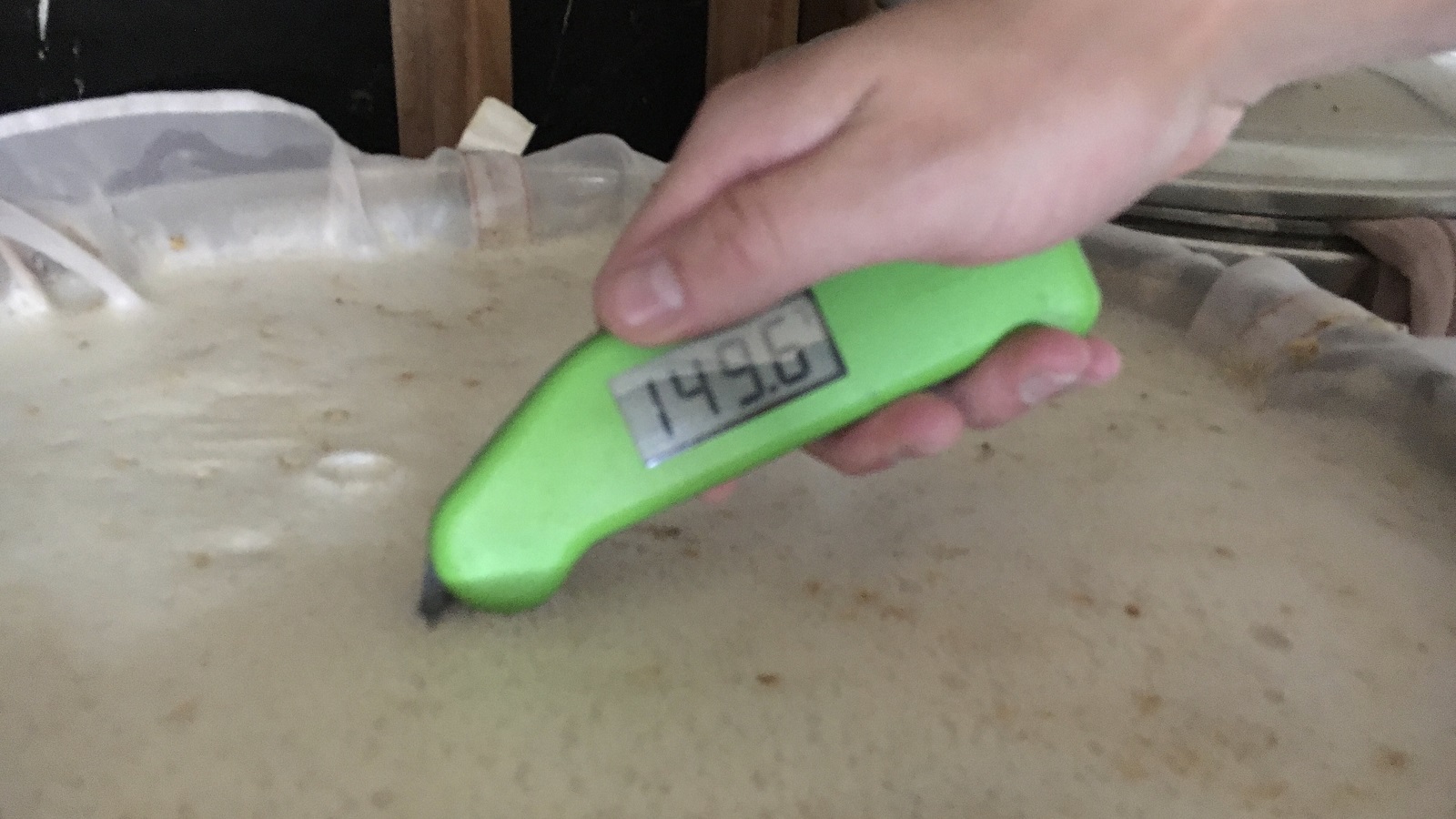

With the water appropriately heated, I stirred in the grist then checked to ensure it was at my target mash temperature.

The mash was left to rest for 60 minutes with intermittent stirring.

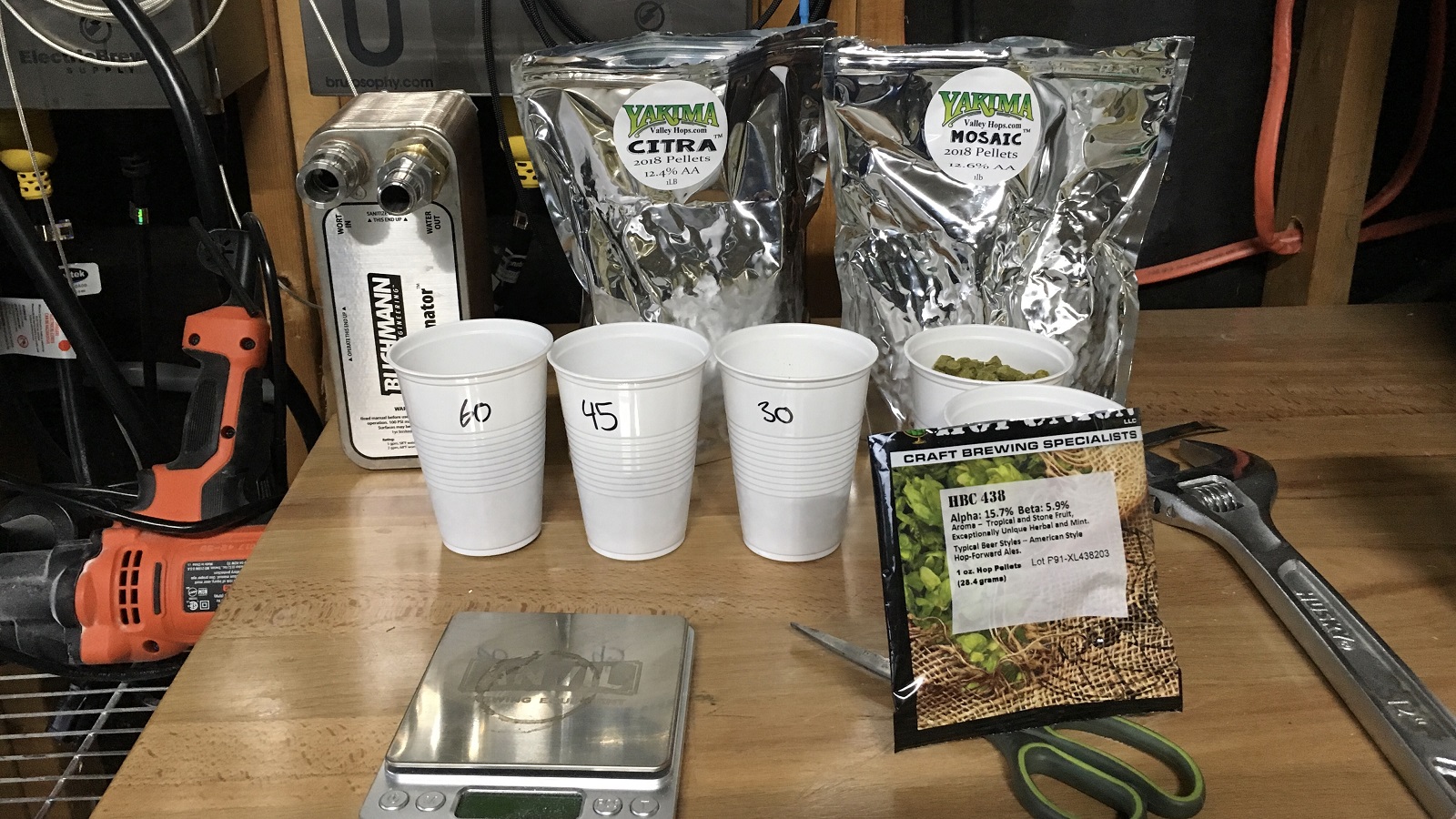

With the mash rest complete, I began transferring the sweet wort from the MLT to the kettle, during which I weighed out the kettle hop additions.

The wort was then boiled for 60 minutes with hops added as stated in the recipe.

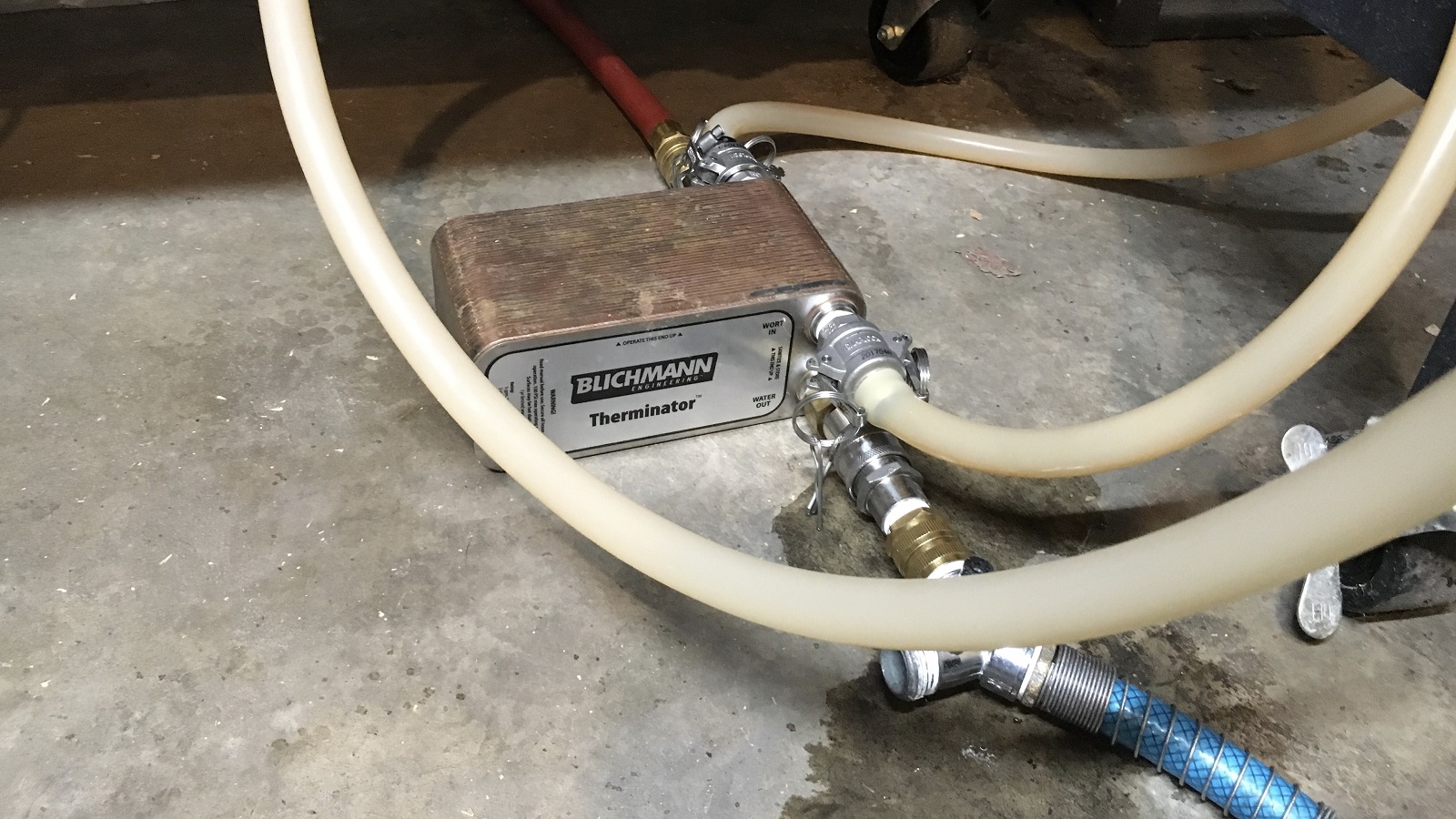

Once the boil was complete, I racked equal volumes to separate fermenters, running it through my plater chiller along the way.

A refractometer reading showed the wort was right at my planned OG.

The filled vessels were connected to my glycol rig and left to finish chilling to my desired fermentation temperature of 66°F/19°C, after which I pitch a single pouch of Imperial Yeast A05 Voyager into each.

The beers began showing signs of activity a few hours later and were left to ferment at the set temperature.

After a week of fermentation, signs of activity were beginning to slow, so I took initial hydrometer measurements showing both beers reached the same FG.

When a second set of hydrometer measurements taken 5 days later showing no change, I proceeded with adding the dry hops. For the non-flushed batch, I measured out the dry hops, placed them in a bag, and let sit in the open air for a few minutes before adding them to the beer. For the flushed batch, after placing the same amount of dry hops in a baggie, I flushed it with CO2 for 30 seconds, squeezed all of the air out, then repeated this 3 more times before adding the hops to the beer.

Once the dry hops were added, I purged the fermenter that received the flushed dry hops with CO2 while leaving the other batch alone. In order to allow any impact of the oxygen exposure to occur, I left the beers alone for 12 days before cold crashing and racking to kegs.

The filled kegs were placed in my keezer and burst carbonated before I reduced the gas to serving pressure. After a couple weeks of conditioning while I was traveling for work, the beers were carbonated and ready to serve to participants.

| RESULTS |

A total of 21 people of varying levels of experience participated in this xBmt. Each participant was served 1 sample of the beer where the dry hops were flushed with CO2 and 2 samples of the beer non-flushed dry hops in different colored opaque cups then asked to identify the unique sample. While 12 tasters (p<0.05) would have had to accurately identify the unique sample in order to reach statistical significance, only 7 (p=0.58) did, indicating participants in this xBmt were unable to reliably distinguish an IPA made with dry hops that were flushed with CO2 prior to being added to the beer from the same IPA where the dry hops were added without being flushed with CO2.

My Impressions: Out of the 5 semi-blind triangle tests I attempted, I happened to guess right 3 times. I perceived the beers as being identical in every respect, neither possessing the telltale signs of cold-side oxidation.

| DISCUSSION |

There’s not a brewer today who doesn’t acknowledge the negative impact oxygen can have on beer, particularly when the exposure occurs on the cold-side. This being the case, it’s understandable brewers would take steps to reduce oxygen exposure, especially when it comes to styles like IPA, as oxidation can turn a bright hoppy beer into a sickly sweet mess in no time. One vector of cold-side oxidation is the dry hopping process, as it typically requires adding hops that have been exposed to the air, hence some have taken to flushing their dry hops with CO2 prior to adding them to the beer. However, the fact tasters in this xBmt were unable to distinguish an IPA where the dry hops were flushed with CO2 from one where the dry hops weren’t flushed suggests the impact may not be as deleterious as some think.

It might assumed that the reason for these results is that the dry hop flushing process did nothing to reduce the amount of oxygen coming into contact with the beer, meaning the lack of a perceptible difference was because both were oxidized. Valid as this may be, neither beer tasted oxidized, in fact both were well received by tasters and maintained a pleasant hoppy character the entire time they were around. An alternative explanation is that the amount of oxygen exposure that occurs when using a standard dry hopping method isn’t enough to cause harm.

The good majority of the beer I brew isn’t dry hopped, so this isn’t a variable I’m terribly worried about. In the instances I do brew IPA, I definitely make an effort keep oxygen exposure to a minimum, from fermenting in sealed vessels to packaging in CO2 purged kegs. Considering my past positive experiences along with these xBmt results, I won’t be purging my dry hop additions with CO2 in the future.

If you have any thoughts about this xBmt, please do not hesitate to share in the comments section below!

Support Brülosophy In Style!

All designs are available in various colors and sizes on Amazon!

Follow Brülosophy on:

FACEBOOK | TWITTER | INSTAGRAM

If you enjoy this stuff and feel compelled to support Brulosophy.com, please check out the Support page for details on how you can very easily do so. Thanks!

20 thoughts on “exBEERiment | Impact Pre-Flushing Dry Hops With CO2 Has On An American IPA”

On a side note, I’m curious as to the differences between using a specific hop (say Saaz) that is 2.8 AA vs 3.2 AA to attain the same IBU. How does the increase volume of 2.8 AA hops impact the overall flavor profile versus the lower volume from a 3.2 AA?

May I be the first (because there will be others) to state that although I am also skeptical of oxidation from dry hops, oxidation often takes time to become apparent. 2 weeks just isn’t enough time.

It was closer to 4 weeks actually—there was a 12 day dry-hopping time. But your point is taken. Usually, if there’s going to be O2 damage in my IPAs, I start tasting it at around the 4-5 week mark. So I echo that this was probably not enough time for any O2 damage to manifest. I do suspect that residual yeast in suspension are able to mop up some (if not all) of the introduced oxygen. It would have been perhaps a more effective experiment if the beers were cold-crashed first then allowed to warm back up to dry-hopping temp. Sill, it’s intriguing that flushed dry hops AND a purged keg resulted in no perceptible difference.

This.

You should do quality control with both samples after a period of aging to test for oxidation, especially since these results are inconclusive

I’m not sure if the beer on the right is less clear, or if it’s just the different background (or my eyes).

I’d be curious to see how the beers, and the taste testers do over time. Signs of oxidation may not show right away. Do you have enough beer left to re-do the experiment in a month or two? Oxidized beer may be more obvious over time.

And on that thought, it would be interesting to do an experiment to see if your average beer drinker could taste the difference between fresh and old beer. Have you done an experiment like that before? You could do an imperial stout and see if it gets better, and an IPA and see if it gets worse over time.

Hop creep might clean up the added O2 that may be added with dry hops.

Great experiment, thanks. Relieves some of the anxiety when dry hopping. Is it correct that you used 50g of Magnum for 60 minutes?

Interesting study, thanks for sharing. Last year I entered my Pale Ale in the Del Mar homebrewers comp in San Diego. The only criticism was oxidation, papery cardboard flavor. It’s tough to beat that when homebrewers.

Then I did an internship at a running brewery. I realized the biggest components are:

1. Exposure of raw materials to air.

2. Exposure of cooling wort to air.

3. Exposure of wort to air in fermenter.

4. Exposure of wort to air during bottling, and the air space in the bottle itself.

The hop study is interesting because it suggests that with refrigerated pelletized hops a small exposure is not significant. It seems you could CO2 blanket the fermenter itself to ensure the wort isn’t exposed as many breweries do.

I made the mistake once of milling grains and leaving them out for a week. And made my first sour …

Cooling is expedited with a plate chiller which is on my shopping list.

And bottling on foam can minimize the air hap.

I like the chiller in your pics gonna have to pick one up!

Why didn’t they brew a NEIPA for this experiment? They are the beers that have brought, more than others, this problem into the limelight? Furthermore, if you are going to bitter that hard, how are you going to give taste testers the chance to perceive any flaws?

My concern with dry hopping has always revolved around opening the chamber, thus allowing o2 to enter. This I believe is adequately addressed by dry hopping while the ferment is active. But residual o2 on, or in the hops? Really? There can’t be significant o2 in pellets. I doubt even whole cone hops contain enough o2 to make a difference.

I agree. If dry hopping after fermentation, I’d rather flush the vessel well. Pellets are pretty solid…hard to see flushing them doing much. If anything, flushing bags that aren’t fully used seems much more important before further storing them.

I’ve been thinking about this quite a lot lately as my last NEIPA turned into a cloudy purple Grimace beer after 6 weeks. I did wind up (thanks to the recommendation here) picking up a FLEX+ fermenter on Black Friday when they were on a big sale and just tapped my first beer. The benefit of the FLEX+ is that you can really reduce the oxygen ingress and seal fermentation from air. I only opened the fermenter once to add the dry hops charge during active fermentation (assuming there was a blanket of CO2 above the liquid) and pressure transferred to a CO2 purged keg. Gotta say the hop flavor was much “brighter” than most beers I’ve made in the past few years, and this one used 3 year old Mosaic leaf hops to bitter.

On a less first world answer, I would think you could simply put a gas line in the top of whatever fermenter you use and push 1-2psi CO2 into the open fermenter as you dry hop to blanket the wort and keep O2 out.

I get the cold-side O2 fetish and have seen directly there’s some value in reducing it. But I can’t believe that opening active an active fermenter for 5 seconds while you dump hops in (even if you do that 3x) is really going to kill your beer. I do think that the process I used for 25 years–open the top of the completed fermentation vessel, stick a racking cane in, and run the liquid into an open corny keg until full–does probably add too much cold-side O2 and resulted in beers that had a pretty narrow peak serving period.

Continue to love your work, even if I don’t agree with all of it. Unfortunately you’ve cost me quite a bit of money as you made me aware of new toys that I eventually bought including the conversion to an electric brewery!

I’m wondering if flushing the dry hop additions might show benefits in commercial beers that set on a shelf or cooler for long periods and/or traveling.

In the brewery we push a little Co2 into our blowoff before we open the manway and during dry hopping. Usually around day 7 depending how the yeast flocs and harvests. We transfer to bright in 4 days and let it sit around 68° till it passes VDK, typically a week, it accounts for the hop creep. Then it’s crashed and carbed and ready to package.

135g of dry hop for 5 gallon is considered moderate? Its near 1oz per gallon. I thought it was a lot? How much per gallon when you want it to taste a lot?

I wish you have would done the test again 1 and 2 months later. Also I am curious as to the color/appearance of the beer at those points as well. I thought the whole idea of minimizing oxygen contact was to extend shelf stability.

I have a chest freezer as a fermentation chamber. I figured the entire chamber most be filled with Co2 from fermentation. I put a empty pint glass in my fermchamber for 2 minutes and then used that glass of co2 to pour onto a candle. The candle went out immediately! So a simple step I have been doing is putting my hops in a glass and putting that glass in my ferm chamber for 5-10 minutes before pouring those hops into my fermonster 2 inch opening. I am completely aware I am a brew geek.

Well, that solves a couple issues. I have only tasted the cardboard side of oxidized beer once, at a music venue, and it wasn’t drinkable. I was expecting a discoloring of the un-purged keg/hops. My dry-hopped beers lately have been turning dark after about 3 weeks and look like dirty dishwater a couple weeks later. They still taste fine. I try to use unopened hops (same brand as above) for dry-hopping. Never had these issues in the past when I didn’t use a closed system and purged kegs. WTF, I suspected the C02 supplier of giving me compressed air, but highly unlikely. In 15 years of home brewing, I’ve never heard of flushing hops until this xBment. The search for answers continues… great article, thanks.