Author: Matt Del Fiacco

Most brewers are familiar with process of bottle conditioning where a sugary solution is used to carbonate beer, typically either corn sugar (dextrose) or table sugar (sucrose). Once added to the beer, the remnant yeast re-ferment this relatively small addition of priming sugar, creating CO2 that gets absorbed into the beer due to it being contained in a sealed vessel.

While sucrose and dextrose are considered standard, curious brewers have been known to rely on various other sugar sources for natural carbonation with the hope it has some impact on flavor. One such sugar is honey, which is an amalgam of glucose, fructose, and a small bit of sucrose, as well as water, wax, and minerals. Most yeasts have little trouble fermenting honey, making it a viable option for natural carbonation that’s particularly interesting for anyone looking to add a hint of honey flavor to their beer.

The idea of adjusting finished beer character by using different priming sugars is one I find quite appealing, as it adds yet another tool to my brewing belt. Though I keg my beer and have essentially abandoned using natural carbonation methods, a recent discussion with a friend revived the idea that carbonating beer with less traditional priming sugars such as honey could potentially impart desirable characteristics. Having never tried it myself, I was excited to put this one to the test.

| PURPOSE |

To evaluate the differences between a beers that are naturally carbonated with either sucrose (table sugar) or honey.

| METHODS |

I figured a straightforward Blonde Ale would allow any differences to show through and designed a simple recipe for this xBmt.

You Are My Candy

Recipe Details

| Batch Size | Boil Time | IBU | SRM | Est. OG | Est. FG | ABV |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5 gal | 60 min | 22.7 IBUs | 3.0 SRM | 1.040 | 1.009 | 4.0 % |

| Actuals | 1.04 | 1.011 | 3.8 % | |||

Fermentables

| Name | Amount | % |

|---|---|---|

| Pale Malt, 2 row (Gambrinus) | 7.5 lbs | 100 |

Hops

| Name | Amount | Time | Use | Form | Alpha % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Centennial | 13 g | 45 min | Boil | Pellet | 10 |

| Cascade | 16 g | 15 min | Boil | Pellet | 5.5 |

Yeast

| Name | Lab | Attenuation | Temperature |

|---|---|---|---|

| Tartan (A31) | Imperial Yeast | 73% | 65°F - 70°F |

Notes

| Water Profile: Ca 68 | Mg 0 | Na 10 | SO4 70 | Cl 65 |

Download

| Download this recipe's BeerXML file |

A couple days before brewing, I made a couple starters of Imperial Yeast A31 Tartan.

When brew day came around, I collected two identical volumes of water then turned on the elements to heat it up.

Next, I weighed out and milled the grain for each batch.

With the water adequately heated, I incorporated the grains then checked to make sure each batch was at the same mash temperature.

During the mash rest, I weighed out the kettle hop additions.

When each 60 minute mash was complete, I removed the grains and brought the worts to a boil.

When the 60 minute boils were finished, they were quickly chilled then blended together to ensure homogeneity before being racked to identical fermentation vessels.

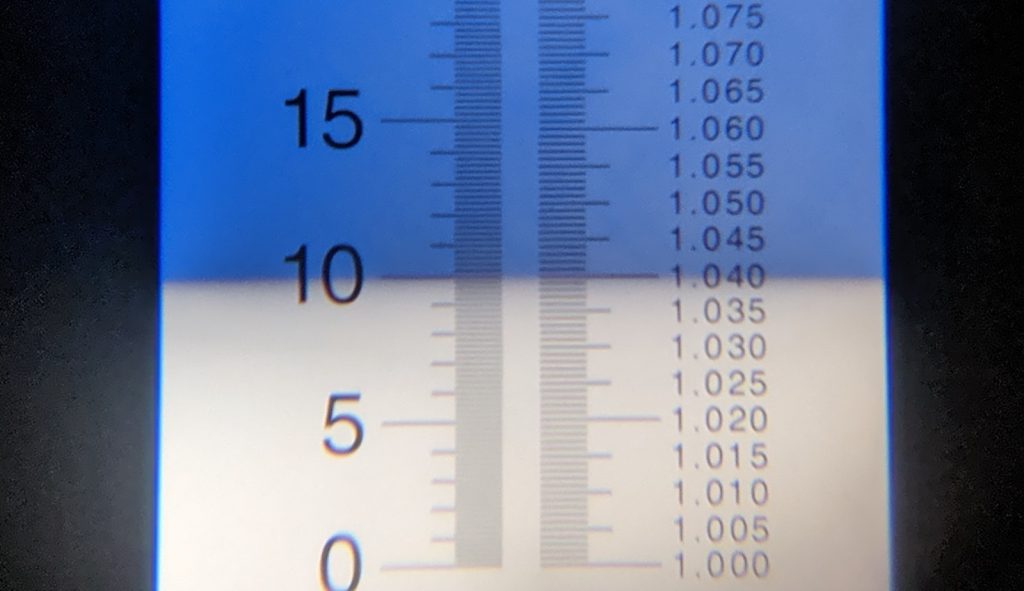

A refractometer reading confirmed target OG was hit.

After placing the fermenters in chambers controlled to 66°F/19°C, I pitched the yeast.

With signs of activity absent after a week of fermentation, I took hydrometer measurements showing both beers were at the same FG.

At this point, I prepared both priming solutions by first using BeerSmith software to determine I would need to use 108.2 grams of sucrose and 131.4 grams of honey to achieve 2.4 volumes of CO2. Then, I boiled each briefly in the same amount of water to dissolve.

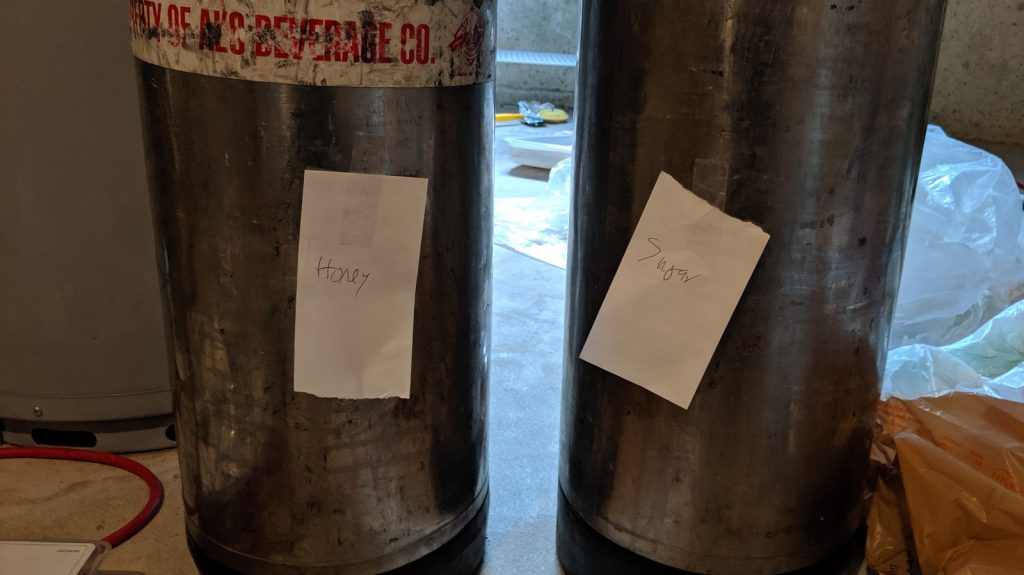

Each priming solution was added to a separate sanitized keg before the beers were racked in.

The filled kegs were placed next to each other in a spot that maintains a fairly steady 68°F/70°C and left to condition.

After 3 weeks, I moved the filled kegs to my keezer and left them to condition for another couple weeks before being served to tasters.

| RESULTS |

A total of 21 people of varying levels of experience participated in this xBmt. Each participant was served 1 sample of the beer naturally carbonated with sucrose and 2 samples of the beer naturally carbonated with honey in different colored opaque cups then asked to identify the unique sample. At this sample size, 12 tasters (p<0.05) would have had to identify the unique sample in order to reach statistical significance, though only 9 (p=0.24) did, indicating participants in this xBmt were unable to reliably distinguish a Blonde Ale naturally carbonated with table sugar from one carbonated with honey.

My Impressions: Out of 5 triangle test attetmpts, I happened to guess correctly 3 times. I couldn’t detect any differences between these beers, despite knowing what the variable was. I perceived both as having a light grain character with a bit of residual sweetness and pleasant piney hop character.

| DISCUSSION |

Naturally carbonating beer is believed by many to produce a noticeably different sensory experience than force carbonation, with some claiming it leads to finer bubbles that positively impact the ultimate character of the beer. Additionally, it purportedly opens up a vector of flavor adjustment unavailable when using external CO2, as various types of sugars can be used for priming, presumably carrying over some characteristics. Interestingly, tasters in this xBmt were unable to distinguish Blonde Ales naturally carbonated with either sucrose or honey, suggesting any flavor impact was too small to be noticed.

Honey can come from many different pollen sources that lead to various flavors and pungency levels. It’s possible the more subtle characteristics of the wildflower honey I used for this xBmt simply didn’t come through when used to naturally carbonate, and that perhaps a stronger flavored honey would have had a bigger impact. Regardless, these results indicate honey is certainly a viable way to naturally carbonate beer, though given the cost, may not be the most economical.

Seeing as I rely primarily on spunding or force carbonation in my own brewing, the results of this xBmt didn’t inspire me to do more natural carbonation and reinforced my inclination to stick with what I know works. However, I remain curious to try this again with notably stronger flavored honeys as well as other sugar sources like molasses and maple syrup to see how it influences beer flavor.

If you have any thoughts about this xBmt, please do not hesitate to share in the comments section below!

Support Brülosophy In Style!

All designs are available in various colors and sizes on Amazon!

Follow Brülosophy on:

FACEBOOK | TWITTER | INSTAGRAM

If you enjoy this stuff and feel compelled to support Brulosophy.com, please check out the Support page for details on how you can very easily do so. Thanks!

22 thoughts on “exBEERiment | Natural Carbonation: Sucrose vs. Honey In A Blonde Ale”

Maybe the honey would come through if you used a noble hop.

Potentially, but I’m curious why you think that would be?

do people typically actually just use sugar? I thought most people used DME. If that is the case, why not try light vs dark DME?

By far the most recommendation I see online is table sugar, and most kits come with either table sugar or corn sugar. Different kinds of extract also sounds like a cool carbonation experiment!

I’ve been using table sugar for years, prior to that I used dextrose. I never saw a real reason to use DME. I’m not actually certain I’ve met anyone who uses DME.

Yes, I think most people that carbonate naturally use dextrose, followed by sucrose, followed by malt extract.

I use Dextrose.

interesting! I’ve only ever used DME (and I think I got that from a Papazian book). What’s the rationale for dextrose? Is the use of DME frowned upon these days?

@brendan Dextrose is supposed to have a completely neutral character, sucrose is supposed to be a little cidery, which is one of those old myths that never seems to go away- I’ve never actually heard of anyone being able to taste a difference in their own or anyone else’s beers. You can use DME if you’re a Reinheitsgebot fanatic, otherwise, you’re really just spending money you don’t need to spend. All my beers are carbonated with plain old table sugar these days. It really makes very little impact.

Why did you burst carbonate? Wasn’t the priming sugar carbonation the whole point of this experiment?

Great catch Eric, I did not burst carbonate these beers. Edited. I’m guessing it was an overlooked article copy/paste.

Nice xbrmt Matt! Although I am not surprised 131 grams of honey did not impart a flavor impact on what would be 7.5 pounds of fermented malt sugars, I do think this has some unique applications to home brewing. I think carbonating with alternate sugar sources such as honey, molasses, or maple syrup could be utilized to reinforce a particular flavor in the finished beer. Maybe use honey in a pilsner to reinforce the honey character in pilsner malt or maple syrup to carbonate a Canadian Breakfast stout type beer. Molasses in a baltic porter perhaps??? This could be particularly useful to someone who was spunding. You would be able to add a bit more sugar than needed for carbonation but still hopefully keep in most of the flavor and aromatics from the sugar source. Maybe someone out there already does this and could comment? Thanks again for all you do. Prost!

I use molasses in dark beers with some regularity, but as a fermentable, not as a priming sugar. It adds some flavor to be sure, but I don’t know how much flavor you’ll get using it just as a priming sugar. The main challenge there is that you’re really adding very little of the fermentable ingredient period- when I’m using it in beers I’m usually using a pound or two. But then, I also haven’t tried it in something like a blonde, where any little addition of color and flavor would be much more noticeable.

Is there a difference in the amount of sugar needed if you were to bottle condition rather than keg condition? I’ve heard less sugar is needed if you naturally carbonate in a keg so I’m curious if you’d notice a difference in the taste if you were to bottle since more sugar/honey may be needed.

Great exbeeriment! As a beekeeper, I often use honey in cooking and in beers. Although I have never used honey as a carbonation sugar, I have often found that when used in beers, I get the most characteristics when adding it in the secondary. I never boil honey, as there is major loss in flavors. If necessary I’ll mix with warm water about 120 deg. F, then cool. This would have probably changed the beer that had honey in it if it weren’t boiled and the flavors would have shined through.

Even if it did impart flavour you could add the honey during or after primary and then force carbonate – it’s not like the flavour is in the CO2 =)

Would be interesting to determine at which point you can distinguish between a beer with added honey and one with just table sugar (keeping ABV the same).

Though I didn’t care for the end result, I found turbinado to have a very pronounced impact on flavor when used as a priming sugar as compared to table sugar.

I have found that I cannot distinguish between dextrose, sucrose, and DME in regards to taste and/or bubbles. Used local syrup for a hefe. Loved it but no one else did. FWIW, I do add about 1/2 the recommended sugar to my kegs, let them sit for two weeks or more then put them on gas. Saves a bit on CO2 and I have found they don’t stale as quickly.

Would love to see a side by side, SMB vs Conditioning.

Thanks for the write up.

“The filled kegs were placed next to each other in a spot that maintains a fairly steady 68°F/70°C and left to condition.”

70 °C = 158 °F 🙂

Interesting test. I really thought the honey would be detectable!

If you ever use molasses, use at most 5g/l, otherwise your beer will taste too much like liquorice, not beer any more. It will work best in dark beers with a final gravity of at least 1.020, like RIS and Belgian strong dark ales.

A good reference for a honey beer is probably Barbãr, from Brasserie Lefebvre.

Why boil the honey? That takes all the aromatics out. You could have just pasteurized it at 170f for 10mins.

Did you seal the kegs with Co2?

Maybe its the beer style or the kind of honey or the palates of the tasters but priming with honey does make a difference.

Listen to The Sour Hour, episode 117 with Kevin Osbourne of Cellador Ales: http://www.thebrewingnetwork.com/sour-hour-episode-117/