Author: Cade Jobe

Professionals and homebrewers alike use finings at different points throughout the brewing process to improve the clarity of finished beer. Due to its wide availability, ease of use, and low cost, gelatin is perhaps the most commonly used of these agents, especially among homebrewers.

Brewers typically add gelatin after fermentation is complete but before packaging, usually once the temperature of the beer has dropped below 50°F/10°C during cold crashing. One notable drawback to this method is that adding gelatin after active fermentation has finished exposes the beer to oxygen, and thus potentially flavor-destroying oxidation. The obvious solution would seem to be to add gelatin earlier in the fermentation process, but that method raises its own concerns. Many brewers worry that adding finings too early could cause under-attenuation, increased ester or phenol production, or reduced body or mouthfeel due to the gelatin binding with yeast and other necessary fermentation reactants.

Curious of the impact adding gelatin earlier in the fermentation process, particularly at the point of pitching the yeast, might have, I decided to test it out for myself.

| PURPOSE |

To evaluate the differences between a beer fined with gelatin during the cold crash and one where the gelatin was added at yeast pitch.

| METHODS |

I went with a simple American Pale Ale fermented with a seasonal English yeast for this xBmt.

Irreparable Damage

Recipe Details

| Batch Size | Boil Time | IBU | SRM | Est. OG | Est. FG | ABV |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5.5 gal | 60 min | 32.4 IBUs | 4.8 SRM | 1.059 | 1.015 | 5.9 % |

| Actuals | 1.059 | 1.01 | 6.5 % | |||

Fermentables

| Name | Amount | % |

|---|---|---|

| Pale Malt (2 Row) US | 9.25 lbs | 75.51 |

| Pale Malt, Maris Otter | 2 lbs | 16.33 |

| Munich Malt - 10L | 1 lbs | 8.16 |

Hops

| Name | Amount | Time | Use | Form | Alpha % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Magnum | 21 g | 60 min | Boil | Pellet | 11.1 |

| Cascade | 14 g | 15 min | Aroma | Pellet | 4.4 |

| Mosaic (HBC 369) | 14 g | 15 min | Aroma | Pellet | 11.3 |

Yeast

| Name | Lab | Attenuation | Temperature |

|---|---|---|---|

| Voyager (A05) | Imperial Yeast | 72% | 64°F - 69°F |

Notes

| Water Profile: Ca 57 | Mg 25 | Na 38 | SO4 93 | Cl 50 |

Download

| Download this recipe's BeerXML file |

I started off my brew day by collecting the proper volume of water, adjusting it to my desired profile, then hitting the flame to heat it up.

While waiting on the water to warm, I weighed out and milled the grain.

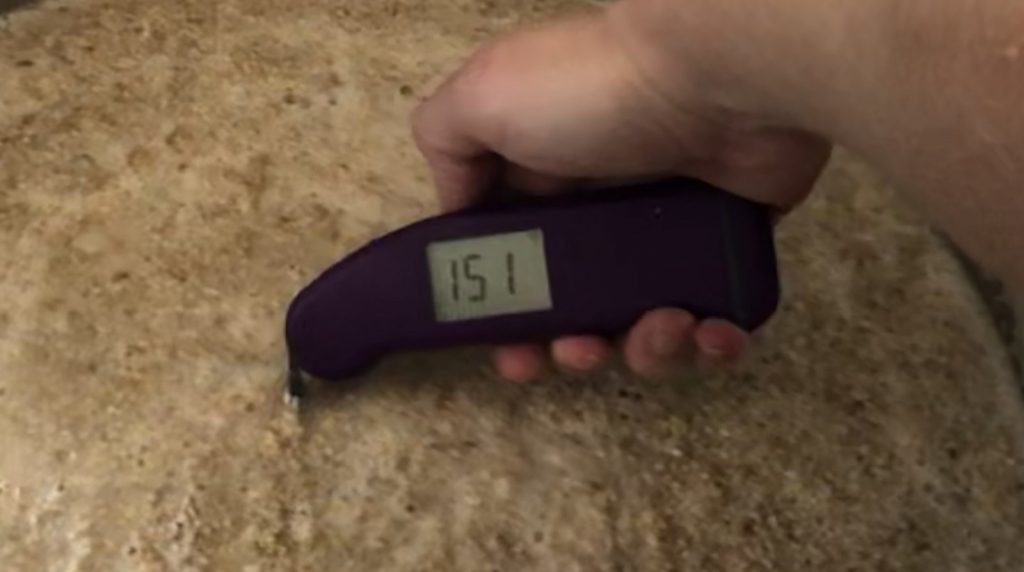

Once the water was appropriately heated, I incorporated the grains then checked to ensure I hit my target mash temperature.

During the mash rest, I measured out the kettle hop additions.

When the 60 minute mash was complete, I sparged to collect the target pre-boil volume then boiled the wort for another 60 minutes before chilling it with my IC.

A hydrometer measurement showed the wort was right at the expected OG.

Equal amounts of chilled wort were racked to identical Brew Buckets that got placed in my chamber to finish chilling to my desired fermentation temperature.

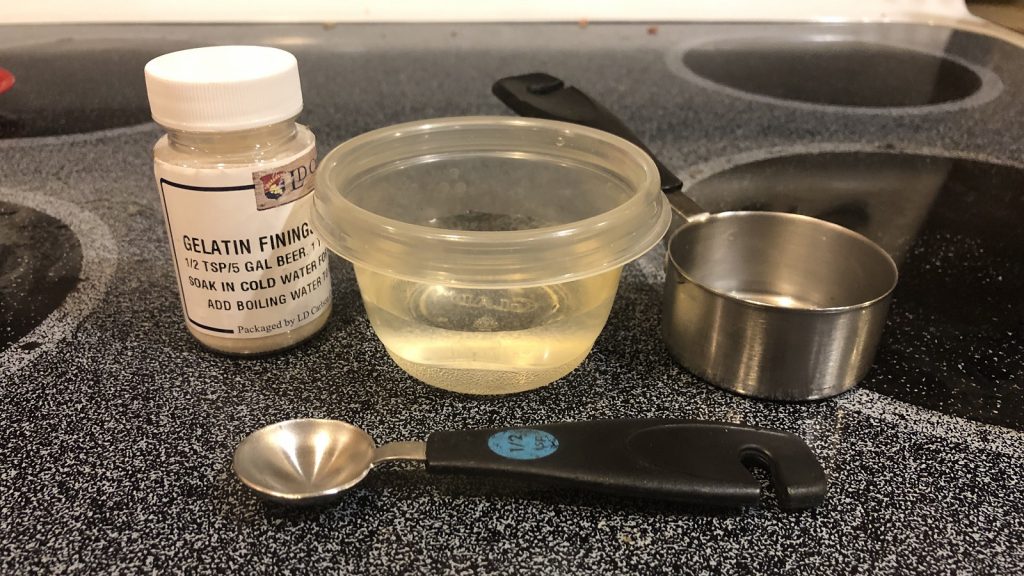

Both worts were stabilized at 66°F/19°C the following morning, so I proceeded with adding a standard gelatin solution to one batch.

Next, each batch was pitched with a single pouch of Imperial Yeast A05 Voyager.

After 9 days of fermentation, neither batch was showing signs of activity, so I took hydrometer measurements indicating they achieved the same FG. At this point, I reduced the temperature in my chamber to 34°F/1°C and left the beers alone overnight before adding gelatin solution to the second beer. Once the beers stabilized at 34°F/1°C, I racked both to sanitized and CO2 purged kegs.

The filled kegs were placed in my keezer, burst carbonated, then allowed to condition for 1 month before I started serving them to tasters.

| RESULTS |

A total of 29 people of varying levels of experience participated in this xBmt. Each participant was served 1 sample of the beer fined with gelatin cold crash and 2 samples of the beer fined with gelatin at yeast pitch in different colored opaque cups then asked to identify the unique sample. While 15 tasters (p<0.05) would have had to accurately identify the unique sample in order to reach statistical significance, only 12 (p=0.23) made the accurate selection, indicating that participants in this xBmt were not able to reliably distinguish beers fined with gelatin at either cold crash or yeast pitch.

My Impressions: Out of the 3 semi-blind triangle tests I attempted, I identified the odd-beer-out exactly 0 times. Even with my intimate knowledge of the variable, I could not tell these beers apart, they were identical to my senses. This definitely wasn’t a bad thing because the beers were quite tasty!

| DISCUSSION |

Whether it’s fear of oxidation from adding finings after fermentation has completed, or concerns over yeast binding with gelatin when it’s added at pitch, it seems there’s no worry-free way to clear beer. My own fear of oxidation has kept me from using it post-ferment, but the fact tasters were unable to reliably distinguish a beer fined with gelatin at yeast pitch from one fined during cold crash suggests oxidation wasn’t an issue in this case and the timing of the addition had little impact on flavor or aroma.

It should be noted the beers were evaluated by tasters at standard serving temperature, as is typically the case for xBmts. I bring this up because I seemed to notice a slight divergence in character as they warmed up. To my palate, the one with the gelatin added at yeast pitch took on a more pronounced yeasty aroma over time, while the beer fined at cold crash largely stayed the same. According to The Oxford Companion to Beer, gelatin’s structure causes it to bind less tightly to yeast than other fining agents, which generally makes it less effective at clearing up yeast-related haze. Indeed, the beer fined at yeast pitch did seem to maintain a stronger haze than the one fined during cold crash, so perhaps I was detecting some residual yeast in suspension. Or maybe some other temperature-sensitive aromatic compound that didn’t bind with the gelatin when added at pitch but did when it was added at crash was present.

While the beer fined during cold crash did appear to clear up more than the one fined at yeast pitch, neither dropped bright, which was disappointing considering the variable in question. Either way, it was still clearer, and seeing as neither seemed to have any oxidation issues, I’ll likely start fining with gelatin during cold crash more often, making sure to employ methods to reduce the potential ingress of oxygen when I do.

If you have any thoughts about this xBmt, please do not hesitate to share in the comments section below!

Support Brülosophy In Style!

All designs are available in various colors and sizes on Amazon!

Follow Brülosophy on:

FACEBOOK | TWITTER | INSTAGRAM

If you enjoy this stuff and feel compelled to support Brulosophy.com, please check out the Support page for details on how you can very easily do so. Thanks!

40 thoughts on “exBEERiment | The Gelatin Effect: Impact Adding Gelatin At Yeast Pitch Has On An American Pale Ale”

Hey Cade, I share your pre-XBMT concerns about oxygen ingress and so don’t fine at all – thanks for testing it out. I notice you didn’t dry hop this one and it seems (insert hyperlinks to previous significant XBMTs here) the effects of oxidation are more accute in a heavily dry hopped beer. Maybe something for a future XBMT…but for now, super useful result for my lagers!! Cheers mate

i found using sheet gelatin helps to save time vs powder stuff. https://www.modernistpantry.com/perfectagel-platinum.html

I didn’t even know that stuff existed. Do you still dissolve it in water before adding to vessel?

I learned about sheet gelatin via the Great British Baking Show (so effin good!) and immediately thought “hey, can I use that for beer?”

Love the exbeeriments and the questions they raise. What did you do to prevent oxygen entering the fermenter during the cold crash? (You guys have your various ways!) Do you know if gelatin is effective when added at higher temps, say 65-70°F? If it is, the fining could be added to the keg at packaging.

I hook up my brew brucket to CO2 at 2ish psi during cold crash. Then, I pressure transfer cold to the kegs.

I’m no expert, but I believe the argument is that adding gelatin before cold crash results in some “chill haze” proteins remaining in the finished beer. I have never tested this personally.

?! I thought you just did test this: wasn’t that this experiment?

Or are you distinguishing between this experiment’s pre-fermentation fining and post-fermentation (but pre-cold crashing) fining?

PZ’s question was about adding gelatin at higher temps, which I assumed meant after fermentation. I haven’t tested adding gelatin at temps above 50F after fermentation.

I use finings at cold crash. I transfer to a purged keg and introduce CO2 at low pressure into the leg at the same time as adding the dining. You can use a standard air nozzle or just an open ended hose.

Hope this helps and thanks for the great info.

Brewbuzzard

FYI, I found the LD Carlson gelatin finings to be ineffective as well. Try the Knox gelatin, it works beautifully for me.

This would explain why neither beer is bright. Gonna say this was a wasted experiment

I second that. Clear, flavorless Knox works wonders.

Very surprised neither of these beers dropped clear. I’ve always had good results using gelatin especially when there was not a dry hop added. Any hypothesis on what is maintaining the haze? Maybe that Voyager strain perhaps? Did they stay hazy until the kegs kicked?

I echo this reaction. When I choose to fine with gelatin I’m looking for bright beer. This recipe (all kettle hops, no dry hops) with this yeast (“Voyager from Imperial Organic Yeast is a highly flocculant yeast strain”) should of dropped clear after a month in the keg without any fining at all. Based on previous experiments would be expecting gelatin at cold crash would clear up the last bit of chill haze. The anticipated comparison beers would of been a clear but slightly hazy beer that experienced no oxygen exposure during fining step vs. a truly bright beer that did take on a bit of oxygen during fining. Then if tasters could not tell the difference between the beers you *might* satisfy yourself that the improved appearance justified the oxygen exposure — at least for the first month in the keg. But without the expected impact on appearance I’m kind of lost thinking about what to make of these results.

Could be something in the mash. Could be a grain issue. Could be chill haze. Could be Voyager, though this was my first experience with the yeast. Could be something else entirely. Haha.

Yes, they’re still hazy.

I’m calling shenanigans on the hydrometer photo. It looks like the two images are of the same beer, the level in the jar is the same, the cracks in the jar are oriented exactly the same, the bubbles on top of the beer are the same, the condensation is largely the same. The only thing different is the focus. It appears as if these photos were taken back to back. I’m not doubting that they both finished the same, only that the photo isn’t genuine.

Funny you should bring this up. I handle all of the photo editing, which in this case meant taking 2 separate FG pics and splicing them together for comparison. I thought the same thing and asked Cade if he mistakenly sent me 2 of the same photo. He assured me they were different and pointed out aspects of each photo that proved they certainly were; he made an effort to take both pics in the same spot so that they did look similar.

I’m not sure what good would come out of lying about FG. In the past when one of us forgot to take 2 hydro pics, we report the actual number and post just the single pic.

The photo is genuine, I promise. The beer level is the same because the tube is broken. I fill it up to the point where it’s broken and then let the hydrometer spill beer over the edge.

Oh come on. Look at the bubbles at the edge of the beer, they are exactly the same. The probability of that from two different samples is zero.

Mistakes happens, it is nice when you can admit them.

Mistakes do happen and I will admit them when they do. This is not a mistake.

you can see a difference in the crack spacing on the back of the collection container.

I love how this is even an issue. How trivial we can be! Ha.

I repeat, zoom in an look at the bubbles. They are identical (even if out of focus on the second photo). Yes, the angle in the second picture is slightly different (as would be expected, they are different photos after all – just of the same motif).

Yes, very trivial, but wouldn’t have been interesting to see if there were any differences in clarity prior to cold crash?

They’re different beers, dude.

Let’s face it Marshall, this finally proves you are part of the Illuminati and this blog is just spreading your Illuminati ways. Next you will try and tell us the earth is round lol.

So you seriously claim that the bubbles are EXACTLY the same due to coincidence, and that there is ZERO probability that you simply mixed up the photos?

OK , whatever.

They are eerily similar pictures. But if you take you focus off the surface bubbles and look at other aspects of the pictures, There are differences. Sorry bro…Illuminati not confirmed here.

I always add gelatin to my cold crashed beer. Sometimes it doesn’t drop bright and remains hazy. Not sure if it’s the grain bill, yeast used, etc. I admit I’ll pop the keg top and add more gelatin to my kegged beer. Usually clears up within 24 hours.

Have to agree with others that both beers are hazier than I would have expected after a month cold storage, especially as there was no dry hopping or even flameout hops. Did you use kettle finings? Could be an issue with the malt, as I’d expect yeast to drop out 100% in cold storage.

I add gelatin differently, based on the first article I ever read on the matter. I rack to keg, let it sit overnight in the keezer (with no gas added), then add gelatin when its chilled to serving temps and start my force carbonating. Seems to work well, although I’ve always been fearful of O2 exposure when I open the keg.

I found cold crashing a waste of time and effort.

Add gelatin to the bottling bucket (1 tsp / 5G) and be done with it.

Have u guys ever looked at a pic of the lunar rover on the moon from the Apollo 15 mission? There is a distinct Brülosophy logo sticker near the front left fender.

Wow! I thought I was the only one who saw it and didn’t want to saw anything. All part of the world domination plan through additions of gelatin to beer I guess. LMAO good eye!

Proves the photo and entire Apollo 15 mission was faked…I put the sticker on the front RIGHT fender! Ah ha!

I have some ideas about on adding gelatin, post-cold-crash, without introducing oxygen. I haven’t actually done this yet, but this is my plan:

Items needed:

1. A clean and sanitized PET bottle.

2. A carbonation cap for a PET bottle (https://smile.amazon.com/gp/product/B01K4GGYT0/ref=ppx_yo_dt_b_asin_title_o07_s00?ie=UTF8&psc=1) with inside line cut to reach bottom of PET bottle.

3. A CO2 tank

4. A liquid-disconnect to FV jumper (my FV has a gas disconnect, so I will use a liquid-to-gas jumper)

5. Gelatin, of course

Step-by-step process:

1. Prepare your sterile gelatin mixture

2. Add gelatin to sanitized PET bottle and attach carbonation cap

3. Completely purge PET bottle by hitting it with a modest amount of CO2 (10+ PSI) and slowly unscrewing the carbonation so that the air can escape. CO2 should flow down the inner line, and bubble up through the gelatin mixture.

4. With the PET bottle purged of air, hit it with CO2 at some pressure higher than that of your FV (my FV is at 3PSI, so I will pressurize the PET bottle to around 10PSI).

5. Sanitize and purge the jumper (how to do so will differ depending on the jumper you use, but it’s trivial)

6. Connect the jumper to the PET bottle and FV. The higher pressure in the PET bottle will push the gelatin up the inner line, through your jumper, and into your FV. If gelatin still remains in the jumper or the PET bottle, just hit the PET bottle with more CO2 and reconnect the jumper until all the gelatin is transferred.

There you have it: oxygen-free gelatin transfers. You can also use the same method to add gelatin or tinctures to your filled kegs. I’ve recently made 30 gallons of cider and I’m planning on adding different tinctures to a handful of the kegs using this method.

Can gelatin reduce the aroma of dry hop?

Has anyone heard of this?

Brulosophy has done a couple exbeeriments on the matter. See https://brulosophy.com/2015/01/05/the-gelatin-effect-exbeeriment-results/

and

https://brulosophy.com/2016/06/20/the-gelatin-effect-pt-6-gelatin-vs-nothing-in-a-ne-style-pale-ale-exbeeriment-results/

Up to now, I’ve always added gelatin after the 3 day diacetayl rest but before cold crash and carb. I always thought it worked as intended. Not sure how the main recommendations of waiting to add gelatin till after cold crash would produce better results. Any input?

My understanding is that gelatine apparently works better when the beer is cold. I’ve always assumed it’s because you want the beer to have the maximum amount of chill haze before the gelatine moves through the beer. Presumably to give the gelatine bigger particles to grab onto. Based on that assumption I fine in the fermenter at about 1C and serve the beer at about 3C. With the exception of one time, all my fined beers have turned out super bright. I use Knox gelatine.

After listening to the podcast, I liked where the discussion was headed regarding future possible experiments. One question I was left with — what would the beer have looked like if NO gelatin was added at all?

I think a great set-up would have been — 1) NO gelatin, 2) gelatin at yeast pitch, 3) gelatin after high krausen, and then 4) the cold-crash addition.

Having a baseline of “no gelatin at all” would’ve provided insight into whether the gelatin at yeast pitch had ANY impact. Cold-crash addition was clearly better (pun intended). But, maybe the yeast pitch addition wasn’t entirely for naught…??