Author: Jason Cipriani

Making sour beer can be intimidating. For some, the added cost of acquiring separate equipment to avoid contamination of future clean beers is enough to keep them from trying it out, though perhaps the biggest deterrent has to do with the time required for the bacteria do its souring magic. Traditionally brewed, a sour beer can take anywhere from 1 to 4 years before it’s ready to consume, much longer than many are interested in waiting.

An approach that has grown massively in popularity over the last few years due to its ability to significantly reduce grain-to-glass time is kettle souring, which involves souring wort prior to boiling and fermenting it. Unlike traditional souring methods, the lactic acid bacteria (LAB) is generally pitched on its own and allowed to blaze its way through the sweet wort before proceeding, reducing the pH to desirable levels in as little as 18 hours.

Kettle souring also adds an element of control not found when relying on methods like sour mashing, as the wort can be pasteurized prior to pitching the LAB to ensure its free from other spoilage microbes.

While there exists many critics of this arguably less conventional method, most who claim it produces beers with lacking complexity, there’s also some disagreement among its advocates regarding proper technique. One very common recommendation, often spun as dogmatic mandate, is that the wort be soured in an environment free of oxygen, as not doing so could lead to the production of isovaleric acid, a compound that reeks of stinky cheese and dirty gym socks.

However, there’s been some talk lately about this not being the case, that the LAB used to sour beer will perform similarly even without such special treatment. As someone who had adopted the anti-oxygen position, I was skeptical of souring in an open vessel and decided to test it out for myself!

| PURPOSE |

To evaluate the differences between a beer soured in an oxygen free environment and one soured in an open vessel.

| METHODS |

I thought a nice Sour Blonde would allow any differences caused by the variable to shine and went with a grist inspired by a clean Blonde Ale recipe of mine.

Coulter

Recipe Details

| Batch Size | Boil Time | IBU | SRM | Est. OG | Est. FG | ABV |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5.5 gal | 15 min | 4.2 IBUs | 4.5 SRM | 1.057 | 1.013 | 5.7 % |

| Actuals | 1.057 | 1.009 | 6.3 % | |||

Fermentables

| Name | Amount | % |

|---|---|---|

| 2-Row - US | 10 lbs | 90.91 |

| Caramel/Crystal 10 - US | 8 oz | 4.55 |

| Honey Malt - CA | 8 oz | 4.55 |

Hops

| Name | Amount | Time | Use | Form | Alpha % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

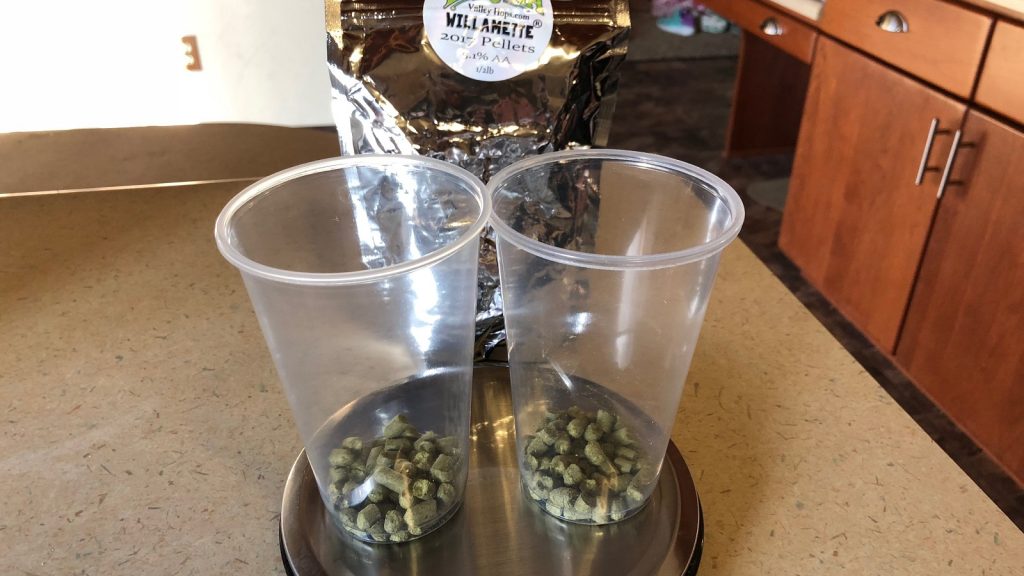

| Willamette | 14 g | 15 min | Boil | Pellet | 5.1 |

Yeast

| Name | Lab | Attenuation | Temperature |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dieter (G03) | Imperial Yeast | 75% | 60°F - 69°F |

Download

| Download this recipe's BeerXML file |

I started my brew day collected the required RO water for both batches then adjusting each to the same profile. While one batch of strike water was heating, I weighed out identical sets of grain and had my assistant help mill it.

Staggering the start of each batch by 30 minutes, I began heating the strike water on the second just as I mashed in on the first; they were treated identically otherwise. Thermometer readings showed both hit the same mash temperature.

While mashing, I heated the sparge water for both batches with my electric heat stick.

The first batch was just coming to a boil when the second batch was sparged.

To reduce the risk of spoilage by unwanted contaminants, the worts were boiled for 15 minutes without hops for the sake of pasteurization before being chilled during transfer to souring vessels.

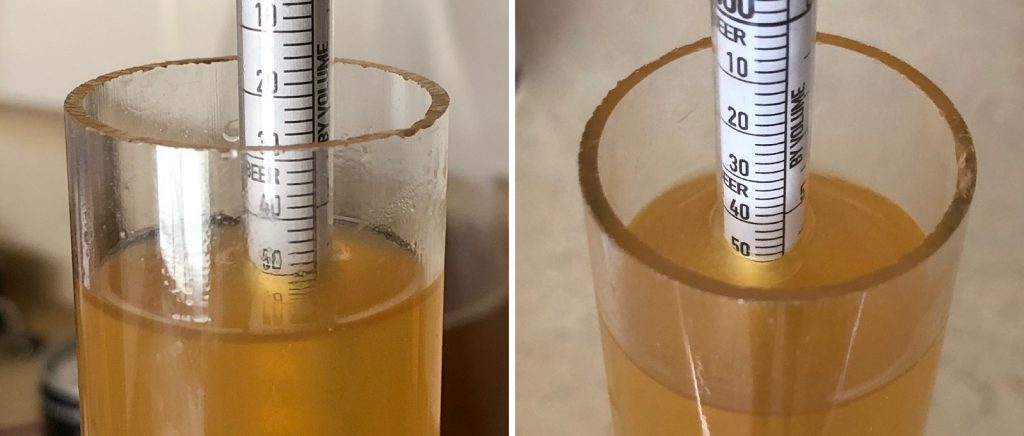

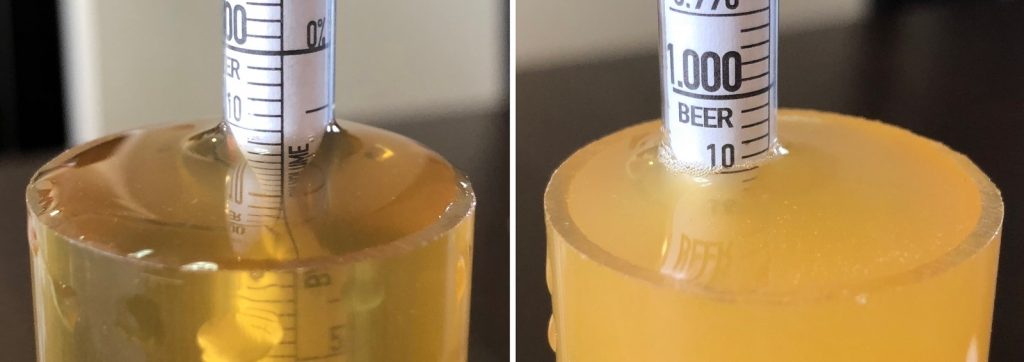

Hydrometer measurements showed both worts had achieved the same OG.

An initial pH measurement showed a delta of 0.06 pH between the worts, not too much, but odd since they were treated identically up to this point.

My souring source of choice for these beers was GoodBelly, which is teeming with Lactobacillus plantarum, a microbe known for its ability to fairly quickly reduce wort pH.

After dosing each wort with the same amount of GoodBelly, I sealed one keg, purged the headspace with CO2, then left the gas attached at low pressure to ensure no oxygen ingress. The opening of the other keg was loosely covered with a piece of sanitized foil to prevent debris from falling in.

At this point, I stole some leftover wort and built equal sized starters of Imperial Yeast G03 Dieter.

I measured the pH after 24 hours and found both worts had dropped about the same relative to their starting pH.

I generally aim for about 3.4 pH when kettle souring, which usually takes about a day, but this ended up being one of the slowest kettle sours I’ve ever made– it took 85 hours for the worts to reach this target pH.

L. plantarum being heterofermentative, a drop in SG is expected as a result of souring and was observed in this instance, though it seemed the wort soured in a sealed keg dropped a bit more than the wort soured in an open keg.

I proceeded with boiling each wort for 15 minutes to rid it of any LAB.

Each wort was hit with a small amount of hops.

At the completion of each boil, I chilled the wort during transfer to fermentation vessels, pitched the yeast starters I’d made on brew day, and let them ferment in a temperature controlled chamber. After a week, I took hydrometer measurements confirming FG had been reached.

Each beer was then pressure transferred to identical CO2 purged Torpedo kegs.

The filled kegs were placed in my keezer where they were chilled and burst carbonated. After a few days of conditioning, they were ready to serve to participants.

| RESULTS |

A total of 18 people of varying levels of experience participated in this xBmt. Each participant was served 1 sample of the beer soured in a closed vessel and 2 samples of the beer soured in an open vessel in different colored opaque cups then asked to identify the unique sample. At this sample size, 10 tasters (p<0.05) would have had to identify the unique sample in order to reach statistical significance, though a mere 3 (p=0.97) made the accurate selection, indicating participants in this xBmt were unable to reliably distinguish beers soured in either closed or open conditions.

My Impressions: Despite the stench from the boil and the bias it undoubtedly produced, I was unable to tell these beers apart in my own semi-blind triangle test attempts, randomly guessing the odd-beer-out just 2 out of 5 times. I enjoyed these beers for their simplicity, though in the future I’ll likely add some fruit post-fermentation to up the complexity a bit.

| DISCUSSION |

Lactobacillus, the most common microbe used for kettle souring, is a facultative anaerobe, which basically means it functions in both the absence or presence of oxygen. Despite this fact, and seemingly based on a few anecdotal reports, many brewers of kettle sour beer strive to limit oxygen exposure during the souring phase for fear of producing off-flavors.

In researching the topic, I discovered little in the way of objective data supporting this notion, mostly just homebrew horror stories and a partially relevant study referenced on the Milk The Funk wiki. Coincidentally, episode 004 of Milk The Funk: The Podcast dropped while I was collecting data for this xBmt, in which the idea that Lactobacillus produces off-flavors in the presence of oxygen was deemed “a myth.”

During the process of making the beers for this xBmt, there were points I was absolutely convinced they were going to be different. During the post-souring boils, the open vessel wort emitted a noticeable aroma of dirty socks that left my wife none too pleased. The odor was so pungent it actually made me a bit queasy, and I began to feel guilty about the beer I would eventually serve to blind participants.

However, in sampling that very beer when it was done fermenting, I was shocked to find the nasty characteristics had completely diminished, its flavor and aroma were the same as the beer soured in a closed vessel to my palate. And the fact blind participants in this xBmt were unable to tell them apart with any consistency lends even more credence to the claim that oxygen exposure during the kettle souring process won’t necessarily lead to off-flavors.

One caveat to this xBmt is that it focused specifically on souring with a known LAB, L. plantarum, and thus the results cannot be extrapolated to include wort soured with other microbes. As such, I’ll likely continue souring under a blanket of CO2 when making kettle sours pitched with a known LAB in the future, if for no other reason than to prevent the smell during the boil, though in those times I detect a stench, I’ll no longer presume the batch is dead.

If you have any thoughts about this xBmt, please do not hesitate to share in the comments section below!

Support Brülosophy In Style!

All designs are available in various colors and sizes on Amazon!

Follow Brülosophy on:

FACEBOOK | TWITTER | INSTAGRAM

If you enjoy this stuff and feel compelled to support Brulosophy.com, please check out the Support page for details on how you can very easily do so. Thanks!

25 thoughts on “exBEERiment | Impact Open Fermentation Has On A Kettle Sour Beer”

you usually use 1 cup of goodbelly per fermenter? i used a whole package in one once, and i could taste mango to the last glass! i also used the Omega strain once and it worked great – made a starter using the milk the funk info.

I have used a whole carton on a 5 gal batch, as well has half a carton in one, both of which I also experienced mango throughout. That’s not necessarily a bad thing, unless you don’t want mango flavor in your finished beer.

If you can find them, the GoodBelly Straight Shots are my go-to. They come in a four-pack of 2.7 oz containers that run around $4, and you can get them unflavored – they’re basically just the lacto in a slurry of mild fruit juice (pear?) and oat/barley milk. I buy mine at Whole Foods, they keep the Straight Shots both with the yogurt and with refrigerated supplements. Minimal added flavor and liquid volume.

Thanks for doing the experiment Jason.

Maybe you should rename your article “…open fermentation with L. Plantarum…”

Although you do state this in a way that is evident to many, some will misinterpret it to be applicable to all kettle-souring methods.

How much goodbelly per 5 gals and what temp did you hold it at?

8oz and 105F/40C

I’ve switched to the purged+sealed method almost entirely due to the pellicle of the open top method. It’s not a huge concern, but the open method creates a pretty gnarly gunk on the surface which I don’t get nearly as much of on the sealed version (oxygen exposure = pellicle, from what I gather)

Keeping that stuff out of the finished beer seems to do a lot of the clarity, and nobody likes floaties in their beer.

Any particular reason you only used 8oz per batch? Why not just split the quart carton between the two and pitch 16oz? I would guess that underpitch of lacto caused the longer than normal souring time. I’ve used 16oz in 5 gals and have achieved a pH of 3.4 in about 30 hours.

I have used 16oz in the past and felt the mango came through in the finished product.

should the wort be aerated pre-goodbelly?

No, Lacto doesn’t need oxygen.

I’ve been told that I need to pre sour the wort by adding lactic acid before preceding with the kettle souring, to prevent other bacteria from introducing off flavours. Any truth to this?

In my experiences, reducing the PH helps prevent off flavors from both spoilage bacteria and wild yeast. Any yeast at 105 degrees is going to produce off flavors, so it is good practice (and not expensive at all) to add some acidulated malt to the mash, or lactic acid to the wort.

Any issues with using same kettle to boil sour beers as regular non sour beers? In terms of preventing cross contamination? I would think the boil would take care of it but just curious.

No issue at all, you are correct that the boil takes care of it.

pre-acidify your wort to 4.5 and pitch a little bit more and it will go in less than 24hrs

Great article, makes me feel even less inclined to kettle sour in a fermenter because it’s much easier to keep in my eBIAB kettle, using the controller to maintain temperature.

Any reason you didn’t use Goodbelly’s straight shots? The original straight shot is oat flavored, which is completely neutral in beer. I’ve had luck using only two shots per 5.5 gallon batch.

I have yet to find them nearby. Cartons are everywhere, but the shots are not… at least in Pueblo, CO.

I had trouble finding the shots in the D.C. area, too. I randomly discovered that Whole Foods sells the shots, but located in a different cooler than the cartons. In my local store, they’re somewhere near the milk. Kind of strange…

My go to bugs are from fat free Chobani. A few good dollips and 80ish degrees will get the job done nicely in a couple days. I do pre acidify to 4.5.

I’ll generally target 3.4 all the way down to 3.3/3.2. I’m a big fan of using light and sweet malts with a ridiculous sour punch in the face.

Ha, Coulter … clever.

What’s the difference between a 15 hour mash (https://brulosophy.com/2018/01/08/mash-length-overnight-vs-60-minutes-exbeeriment-results/ and kettle souring? Does the presence of the grain prevent a drop in ph?

Maybe those awful smelling compounds produced while having access to oxygen got boiled off?

Why two separate mashes? Why not do one 10 gallon mash and split the batches into different souring vessel’s? Not criticizing just curious about the process of the experiment and if I am missing anything.

Any risks of oxidation leaving the wort exposed to oxygen for 24-48hrs while souring? If I sour in an unpurged kettle, for example, with just the lid on or at most, some plastic wrap across the top opening and then the lid on top of that will the wort oxidize and stale? Literally doing my first kettle sour this weekend…