Author: Marshall Schott

Ludwig Narziss, largely recognized as one of the world’s foremost brewing experts, recommends wort be separated from kettle trub prior to fermentation in order to produce the best tasting product. Using a mechanical filtration system is the only way to eliminate trub from wort, but due to how unreasonably cumbersome such a process is, brewers tend to rely on simpler methods to reduce the amount of trub in their wort such as racking to the fermentation vessel after a period of settling.

With the effort many invest in trub removal, it’s surprising how little consensus there is on how it actually impacts beer. There are those who contend the gooey gunk imparts a “yeasty” off-flavor, while others seem more concerned with its role on clarity. But ultimately, any attempt to grasp the gestalt of kettle trub hatred left me convinced the parts may not necessarily add up to a greater whole.

Indeed, there’s evidence suggesting the terror over trub may not be necessary, that it has no effect on flavor and may in fact positively contribute to healthy fermentation. Corroborating this notion are our past xBmts demonstrating higher amounts of kettle trub not only led to more vigorous fermentation with faster attenuation, but that it had little if any perceptible impact.

One thing both prior xBmts had in common is that the beers were packaged and consumed relatively soon after being brewed, causing some to wonder if the time on trub might have a greater effect. I was curious to find out!

| PURPOSE |

To evaluate the impact the amount of kettle trub during fermentation has on German Pilsner fermented cool and aged in primary for an extended period of time.

| METHODS |

The recipe I settled on for this particular xBmt was a simple one that would mark my first time using Mecca Grade Estate Malt, with Pelton making up the large majority of the grist.

Pheurton

Recipe Details

| Batch Size | Boil Time | IBU | SRM | Est. OG | Est. FG | ABV |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5.5 gal | 60 min | 31.5 IBUs | 3.9 SRM | 1.051 | 1.014 | 4.8 % |

| Actuals | 1.051 | 1.011 | 5.2 % | |||

Fermentables

| Name | Amount | % |

|---|---|---|

| Pelton (Mecca Grade) | 9.625 lbs | 90.59 |

| Vanora (Mecca Grade) | 1 lbs | 9.41 |

Hops

| Name | Amount | Time | Use | Form | Alpha % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Perle | 12.5 g | 60 min | First Wort | Pellet | 8.3 |

| Perle | 15 g | 30 min | Boil | Pellet | 8.3 |

| Perle | 30 g | 5 min | Boil | Pellet | 8.3 |

| Perle | 30 g | 3 days | Dry Hop | Pellet | 8.3 |

Notes

| Water Profile: Ca 75 | Mg 1 | Na 10 | SO4 84 | Cl 70 | pH 5.5 |

Download

| Download this recipe's BeerXML file |

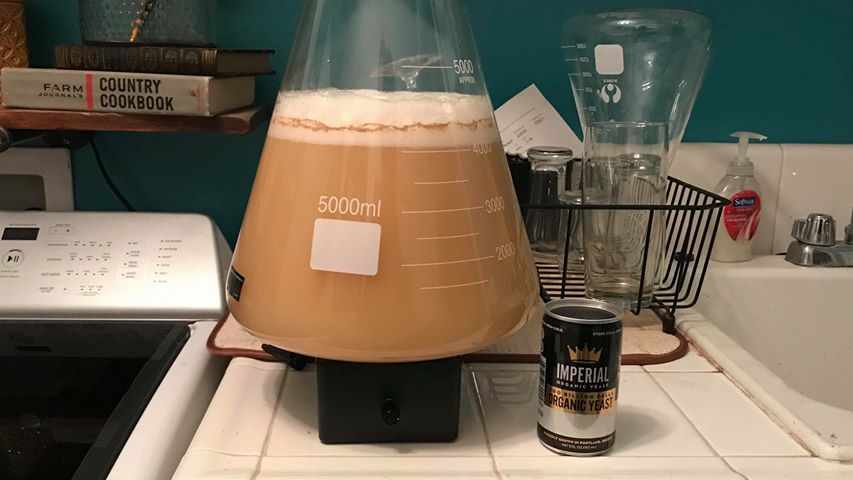

Since these lagers would be fermented cool, I made a single large starter with 2 packs of Imperial Yeast L13 Global 3 days ahead of time.

After moving the fully fermented starter to my garage fridge 2 days later to cold crash, I moved on to weighing out and and milling the grain for a single 10 gallon batch.

I then collected the full volume of filtered water and adjusted it to my desired profile, after which I dropped my heat stick in, put the MLT cover in place, and set my timer to turn on a few hours before I planned to brew the following morning.

With my strike water at the right temperature the following morning, my kids helped me mash in before heading off to school.

A check of the mash temperature once the grains were fully incorporated showed I was right where I wanted to be.

I replaced the lid and let the mash rest for an hour, stirring every 20 minutes to encourage conversion, before collecting the sweet wort.

The wort was boiled for 60 minutes with hops added at the times stated in the recipe.

When the boil was finished, I quickly chilled the wort to 70°F/21°C, which was slightly warmer than my groundwater temperature at the time.

After confirming the wort hit my target 1.051 OG, I placed a piece of wood beneath the front edge of my kettle so that the hops and break material would settle toward the back.

After 15 minutes of settling, I filled the first carboy with very clear wort. Then I removed the wood and began filling the second carboy, using a sanitized spoon to coax as much trub as possible out of the kettle. Mission accomplished.

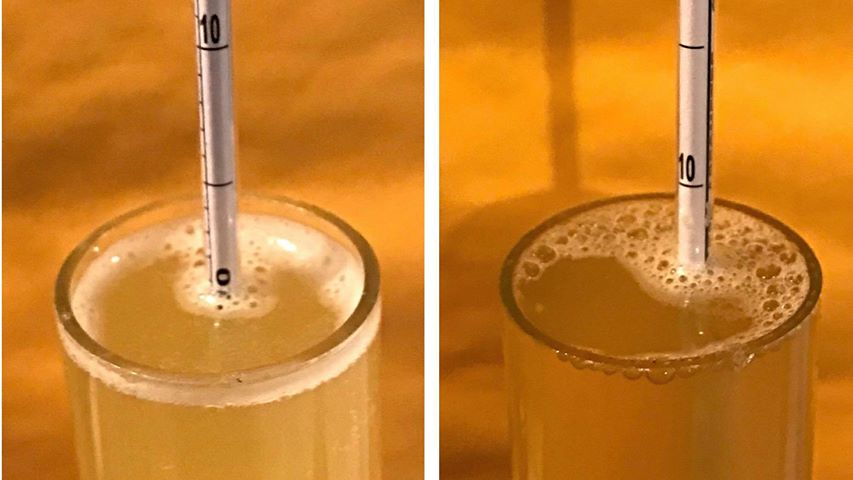

For fun, I took a time-lapse video of the worts over the course of about 20 minutes to observe the trub settling.

The carboys were placed next to each other in my chamber and allowed to finish chilling to my target fermentation temperature of 50°F/10˚C, which took about 7 hours, at which point I split the decanted starter equally between the batches. Unlike previous observations, the high kettle trub batch didn’t seem to start fermenting any sooner than the low trub beer. However, it did appear to ferment with more vigor as evidenced by more observable airlock activity and quicker falling of the kräusen.

Hydrometer measurements 2 weeks after yeast pitch revealed the low trub batch was a bit behind the high trub beer.

At this point I added the dry hop addition then let the beers remain at 50°F/10°C for another week before taking a second set of hydrometer measurements showing the high trub beer had reached FG while the low trub beer hadn’t changed much at all. Seeing as it had been 3 weeks, I raised the temperature of the chamber to 60°F/16°C in hopes of encouraging complete attenuation. After another week, 4 total since pitching the yeast, the low trub beer was sitting at the same 1.011 FG as the high trub beer.

To reduce the risk of oxidation, I kegged the beers without first cold crashing them, making note of the trub at the bottom of each carboy.

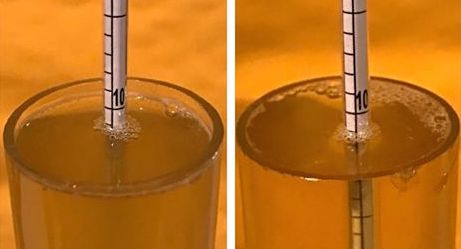

Skipping my typical gelatin fining process, the filled kegs were placed in my cool keezer on gas to carbonate. I stole some samples to satiate my curiosity a week later and noticed the beers looked quite a bit different.

I finally began collecting data 4 weeks later, 5 since packaging, and noticed time didn’t seem to have much of an impact on appearance.

| RESULTS |

A total of 20 people of varying levels of experience participated in this xBmt. Each participant was served 2 samples of the low kettle trub beer and 1 sample of the high kettle trub beer in different colored opaque cups then asked to identify the unique sample. At this sample size, 11 tasters (p<0.05) would have had to identify the unique sample in order to reach statistical significance, while a total of 13 (p=0.004) made the accurate selection, indicating participants in this xBmt were able to reliably distinguish a Pilsner fermented with a lot of kettle trub from one fermented with very little kettle trub after a period of aging.

The 13 participants who made the accurate selection on the triangle test were instructed to complete a brief preference survey comparing only the beers that were different. A total of 7 reported preferring the low kettle trub beer, 2 liked the high kettle trub beer more, 3 had no preference despite noticing a difference, and 1 person reported they perceived no difference between the beers.

My Impressions: Even after 15 years, I still get excited about every batch I brew and look forward to tasting the hydrometer samples. In doing so with these beers, it was pretty obvious to me they were different, which certainly could be explained by bias. Except in a series of triangle tests served to me by others, I identified the odd-beer-out on all 7 of my attempts. I’m not sure if how to describe the aroma and flavor I perceived in the high trub beer that was absent in the low trub beer, it was just different, noticeably so. The best I could come up with was “flubber,” which I’ve never actually tasted, it’s just what I imagine it tastes like. While I definitely preferred the low trub beer, I didn’t have a problem finishing off both kegs, though I’d be inclined to not shove such a large amount of trub in my fermentor in the future.

| DISCUSSION |

In Principals of Brewing Science, George Fix explains that while the high amount of unsaturated fatty acids in kettle trub “contribute to yeast viability” and “inhibit the formation of some less pleasant acetate esters,” they also negatively impact head formation and, even worse, expedite beer staling. He goes on to say that these issues are due to how resistant these unsaturated fatty acids are to oxidation, hence they “spill over into the finished beer where they tend to produce fatty or goaty notes.”

The observations during this and prior xBmts on the same topic corroborate claims that higher amounts of kettle trub encourage more vigorous and quicker fermentation. Where this xBmt differs from those in the past is in the fact participants were capable of reliably distinguishing the high kettle trub beer from the low kettle trub beer, and most preferred the latter.

Considering the first 2 kettle trub xBmts were packaged 13 and 18 days after yeast pitch, it’s plausible the amount of time beer spends in contact with trub has an impact. If this is in fact true, then it stands to reason that the beer fermented with a high amount of kettle trub may not have developed those distinguishing characteristics had it not been in contact with the trub for as long as it was. For the third time now, we’ve demonstrated that kettle trub seems to be beneficial for fermentation, perhaps racking moderate amounts to the fermentor and packaging when fermentation is complete is the best of both worlds.

As for me and my brewing, these results haven’t motivated me to make any drastic changes, I’ll continue not worrying too much about what makes it to my fermentors without intentionally moving all the trub over, as I appreciate the impact it has on both fermentation and clarity. I am curious to explore the effect oxygenation and gelatin fining have on beers fermented with low amounts of trub. Things to come!

If you have any thoughts about this xBmt, please do not hesitate to share in the comments section below!

Support Brülosophy In Style!

All designs are available in various colors and sizes on Amazon!

Follow Brülosophy on:

FACEBOOK | TWITTER | INSTAGRAM

If you enjoy this stuff and feel compelled to support Brulosophy.com, please check out the Support page for details on how you can very easily do so. Thanks!

45 thoughts on “exBEERiment | Kettle Trub: Impact Of Age In A Cool Fermented German Pils”

Hey, guys, you should have an editor reread before posting. 50F=10C, and there are a couple of paragraphs not completely finished.

I disagree, a blog post is not a book. They are supposed to be quick journal entries. Proof reading and editing are unnecessary. I expect, and forgive, mistakes in blog entries.

I appreciate that… but we really do try to be as “professional” as possible. Not to defend myself, but this article was finished over my birthday weekend, and I like to party.

Sometimes updates don’t go through. All fixed now.

Perhaps you can make this point with a little less snark? The Brulosoohy crew does so much work for all of our benefit. Some appreciation, I think, is justified.

Very interesting. I was hoping they might taste the same, so I can ditch my time-consuming process of racking wort off the trub to the fermenter and then filtering the residual egg-drop-soup through a muslin-lined funnel to recover an extra 3-4 pints of clear wort. Alas I think I’ll have to continue.

Nice time lapse and it’s interesting to see that the break material had packed down to a much denser, thinner layer after fermentation ended and the yeast settled. Also the better clarity is interesting to those of us who don’t fine. If there’s a way of getting these benefits without the flavour being affected, that would be amazing to know.

Instead of filtering, I’ve often transferred the soupy material to a big sanitised jug, left it in the fridge overnight to settle and then added the residual wort to the fermenter. It works pretty well.

hmm, this may explain the flavor difference in a Bo Pils I brewed a couple months ago that’s still on tap. It was a 10 gallon batch split between 2 carboys. I racked them both from my kettle, one with barely any trub and the other with all the rest, thinking from your previous xbmts it would make no difference. One of the beers seems to be showing signs of oxidation with some sweetness and dark fruit notes while the other still tastes clean and crisp. They were both treated identically throughout the process, but taste starkly different. Maybe this difference is much more noticeable because the beer isn’t hiding behind hops. I’ve never had this problem with pale/IPA’s

Which is showing signs of oxidation?

The one with trub.

Very interesting. I kind of expected this one to come back non-significant based on the results of past exbeeriments. That said, extended time on the yeast has long been purported to . have various effects (“good” and “bad”) so I suppose it’s not too surprising.

I think an interesting addition to these articles which could be tacked on in the future would be the “shelf test”. Package up at least a couple of bottles of each beer, then label them and re-visit them after say, 3-6 months of “shelf time” at a reasonable temperature.

Then the articles author could publish an addendum to the original article. Even if it’s not the full triangle test, it would be interesting to see what (if any) noticeable effects almost all of the variables being tested in these experiments look like after a few months on the shelf. Like what you might find from a commercial brewery. It might help explain why they do some of the things they do, and shed some light on which variables have strong effects on shelf life.

Keep up the awesome work!

Looks like the trub in suspension helped drop out the yeast. Clarity without added steps. Nice. This particular Malt bill and technique is worth exploring getting off the trub when the yeast is done and it drops clear.

Did you only raise the temp on one beer for the extra week in primary or both?

Both. They were treated exactly the same with the exception of the trub.

Thanks!

What would you be inclined to do? There’s a hanging sentence at the end of your impressions.

It’s interesting that there’s such a strong preference for the low trub beer, that seems uncommon based on past experiments (not limited to trub experiments)

Fixed.

thanks! two paragraphs trail off without endings…

The next extension of this experimentation could be to run both batches through a filter post-fermentation, and then test them at initial serving, and 2 months later — to see how/when/where trub/filtration affect taste and stability.

Cool experiment. I love the time-lapse, but it made me wonder how long it takes for sunlight on a clear carboy to produce skunked flavors?

There’s a google search for y’all. Could there be much more IBU in the trub than in the clear beer?

I wonder how allowing some grub into primary for a healthy fermentation, but then racking to secondary for the dry hop and diacetyl rest would’ve affected things.

Also, given this was your first time using Mecca grade malt, I would love to hear your thoughts compared to buying the regularly available malt from weyermann, briess, etc.

Great job on this one! I love the time lapse video. So many aspects could be discussed from this experiment. Time on yeast cake? How much trub is just right? Should we always fine our beers? It could be a great explanation of why transferring to secondary has been preached for so long in the Homebrew community. It also seems to still point out crystal clear wort into a fermentor is maybe not the best thing either. Marshall, have you ever had the “flubber” taste before in any of your beers?

Love the time lapse video. Really neat to watch the dropping process. Thanks for the little bit of excitement.

Did you notice there was a difference in head retention between the two beers?

I seldom attempt to keep trub out of my beers, since it does help with clarity, yeast health, and compacts down just fine after fermentation….but I also have issues with head retention that I am trying to track down.

Both beers had similar head retention.

one thing i noticed about head retention in my own beers is that i was having poor head retention in beers where i didn’t add any hops or hop extract to the boil (eg only to the hopstand.) Once I started adding in even 10-20 IBUs of bittering hops each time at 60 mins I started getting good head retention again.

Is it just me or does the high trub beer look way clearer than the low trub beer?

Great experiment!

Waaaaaaay clearer. That’s been the case in every kettle trub xBmt so far.

That just seems so crazy to me…maybe I’m still an amateur brewer but If I went in with no brewing knowledge I’d predict the opposite 10 times out of 10

seems like a lot of big particulates in the wort act as fining agents. trub contains proteins and isinglass is a protein so it makes sense if you think about it.

Great stuff Marshall as usual! It’s always great when one of your exbeeriment’s lines up with what I’ve been doing in practice for quite a while – admittedly somewhat out of laziness. I brew mostly English and Scottish ales and package right into the keg once fermentation is complete and I have clear beer that tastes great. But…as I’ve recently started doing some lagers thanks to your exbeeriments on fermenting lagers at ale temperatures, if I did want to lager one for a while it might make sense to at least rack after a week or so. Thanks again and keep up the good work!

Marshall…curious if you think an exBEERiment would be worth while in moving a high trub beer into a secondary after reaching FG and letting the low trub beer go as you did in this exBEERiment and recording the results? Might get the best of both worlds and give merit to moving to a secondary after all…or maybe it introduces too many variables at once??? I do appreciate that racking to a secondary opens up another can of worms though, not to mention additional work, (reference your exBEERiment on “Primary–Only vs. Transfer To Secondary” on 8/12/2014) and with all due respect, could potentially cause you to rethink NOT transferring to a secondary??? Or could further substantiate your your results of staying in the primary??? Would love to hear your speculation on this even if you don’t do the exBEERiment…I’d be satisfied with your educated guess. Thanks for the work you put into ALL your exBEERiments…seems like anytime I have a question you’ve already done the hard work…thanks again.

So, my thinking on this concept is that, as someone who kegs, why wouldn’t I just package the beer sooner, like as soon as it’s done fermenting, which is fairly quick when trub is included in the FV?

Actually, now that I think of it, no reason this wouldn’t work for bottle conditioning as well. As long as fermentation is complete, package that stuff up!

Exactly, one could rack to a keg, then lager in the keg and package in bottles (force carbed or natural) at a later date.

Hi Marshall… I am curious as to whether you think the only variable of difference between the beers is the trub? Have you considered separating the wort from the trub and tranferring well mixed clear wort into two fermenters and then adding the remaining trub back into one batch? Could there be something in the first run of wort from the kettle (the deeper wort, but not the trub) and not in the second run (with the trub) that has an impact on the result?

Why we remove trub?

Cloudy wort can contain anywhere from 5 to 40 times the unsaturated fatty-acid content of clear wort, an important fact because unsaturated fatty acids can have a significant negative effect even at low concentrations. What effect?

1. they work against beer foam stability

2. they play an important role in beer staling

This is discussed by Narziss, Kunze, and Noonan. The purpose of this series of xBmts is precisely to test these claims. Over the 3 trub xBmts, point #1 has not been something I’ve observed, and I’m not convinced the difference noted in the latest iteration was a function of staling. Only conjecture at this point.

Sure thing, although foam retention is also affected by parameters like length of boil and the veracity of the boil according to Kunze. I would like to say though that use of products like Polyclar Brewbrite (a PVPP/carrageenan) mix produce a particularly clear wort if the course break is simply left to settle out. There is no need for mechanical filtration or even a whirlpool.

You should repeat this with a cold crash/lagering step to see if extended exposure to yeast/trub at lagering temps has an even greater or maybe lessens the effect noted on this exbeeriment.

As you have often shown, many variables make no difference on their own. If you have good process you can skip lots of things. But I wonder if there are a few things which have been considered non significant in the past that might be significant in this situation in managing trub flavour. In other words if traditional brewing lore links together 2-3 different ways of managing a problem into the process then removing any one will not return a difference as the remaining ones still work.

In this case it’s hard to imagine that racking to secondary after a day or two or even a few hours of settling might not solve the problem and be easier than filtering. Also as you say if packaging asap was enough then let’s just do that.

They key thing here is to find the best, easiest way to manage the problem. Which is that filtering out the trub is difficult but has a negative impact on flavour.

The other challenge here is that you clean wort was super clean. Could you still tell the difference if you had not deliberately stirred the trub. It would be nice to see the next one replicate more ‘normal’ processes.

one had no visible trub. the other probably had close to 10G of trub. an extreme comparison. do one with one and one with a usual amount and there will likely be no flavor difference i would guess

2 weeks is a long time for fermentation. I recall a paper that discussed using a micro-drop of olive oil to improve yeast health and fermentation – as an alternative to infusing oxygen through shaking or a stone. Maybe you could redo this experiment and add a micro-drop of oil (or oxygenate the trub-less) to get the fermentation times to more closely match the other carboy.

Otherwise, this difference could just be byproducts of a weak fermentation.

I am a Super Truber…by that I mean that I do stovetop BIAB, dump the entire kettle into the carboy, and never use move beer off the trub to a secondary. At first, I was a bit disappointed in the results of part 3 (as compared to pt 1 and 2), but here’s how I am choosing to take it.

Your conclusion in the podcast is that some amount of trub is probably better than no trub for clarity, taste, etc. but there’s an inflection point before it starts to detract. Well, in your exBeeriment it was…

Zero trub in 1/2 batch vs. Full trub in 1/2 batch

I’ll stick with the idea that Full trub spread throughout a full batch is just about right 🙂

I think the flavor assessment may have been more influenced by the relative dryness of the trubby beer, rather than any oxidation or other off flavors. In a dry beer at 1.012 FG you’ll naturally detect more subtle flavors.

I wonder what the results of an experiment would look like if you compared the normal process of brewing to a trubby process where you rack off of the trub after only one or two days of fermentation. Would you get all the benefits without the off-flavor? Could you save a transfer and effectively be fermenting in your secondary vessel after only a couple days? If your secondary vessel is a keg, could you just serve out of that?

This would be very helpful knowledge to anyone who ferments in the kettle or ferments in kegs.