Author: Marshall Schott

I learned of first wort hopping years ago when someone on a homebrewing forum claimed it was a method used by German brewers as a way to retain aromatics from hops despite their presence throughout the entire boil. This sounded bogus to me, but given how easy the method was, I gave it try, didn’t notice any detriment to my beers, and began swapping out nearly all of my bittering additions with first wort hop additions. Anecdotally, I didn’t notice much of a qualitative impact from this method, so I decided to put it to the test and had a bunch of 2015 National Homebrewers Conference attendees participate. The results from that xBmt validated my experience, the beers were largely indistinguishable, though I’ve continued using the method as a way to eliminate the volcanic eruption that often occurs when adding the first dose of hops to boiling wort.

Since a single data point does not a principle make, and given my regular use of first wort hopping, I figured it was time to revisit this variable. Coincidentally, For The Love Of Hops author, Stan Hieronymus, published a fantastic blog post on this very topic while my beers were being made. After acknowledging that his prior suggestion to first wort hop in order to impart a “finer” bitterness was largely based on anecdotal evidence, he reported on new research from Oregon State University that aligned nicely with our 2015 xBmt– participants could not distinguish a first wort hopped beer from one brewed with a standard 60 minute kettle hop addition. Stan went on to discuss the history of first wort hopping as well as other fascinating aspects of the technique, which made me all the more interested to see how my second attempt would turn out!

| PURPOSE |

To evaluate the differences between a beer brewed using the first wort hop method and the same beer made with a standard 60 minute bittering addition.

| METHODS |

In an attempt to isolate the variable as much as possible, I designed a very simple beer with but a single hop addition.

Grendel

Recipe Details

| Batch Size | Boil Time | IBU | SRM | Est. OG | Est. FG | ABV |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5.5 gal | 60 min | 25.4 IBUs | 3.4 SRM | 1.052 | 1.013 | 5.1 % |

| Actuals | 1.052 | 1.008 | 5.8 % | |||

Fermentables

| Name | Amount | % |

|---|---|---|

| Pilsner (Weyermann) | 9 lbs | 85.71 |

| Vienna Malt (Weyermann) | 1.5 lbs | 14.29 |

Hops

| Name | Amount | Time | Use | Form | Alpha % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

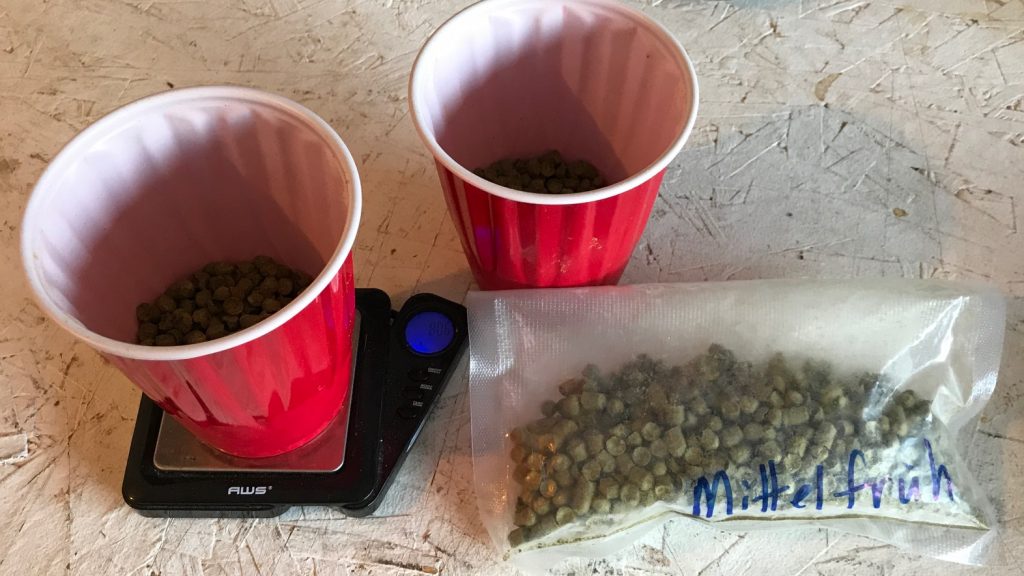

| Hallertauer Mittelfrueh | 80 g | 60 min | First Wort | Pellet | 2.4 |

Yeast

| Name | Lab | Attenuation | Temperature |

|---|---|---|---|

| Urkel (L28) | Imperial Yeast | 73% | 52°F - 58°F |

Notes

| Water Profile: Yellow Balanced in Bru’n Water Spreadsheet |

Download

| Download this recipe's BeerXML file |

I made a starter of Imperial Organic Yeast L28 Urkel 2 days ahead of time.

The night prior to brewing, I weighed out and milled the grain for a 10 gallon batch.

I then collected the full volume of brewing liquor, which I ran through a carbon filter.

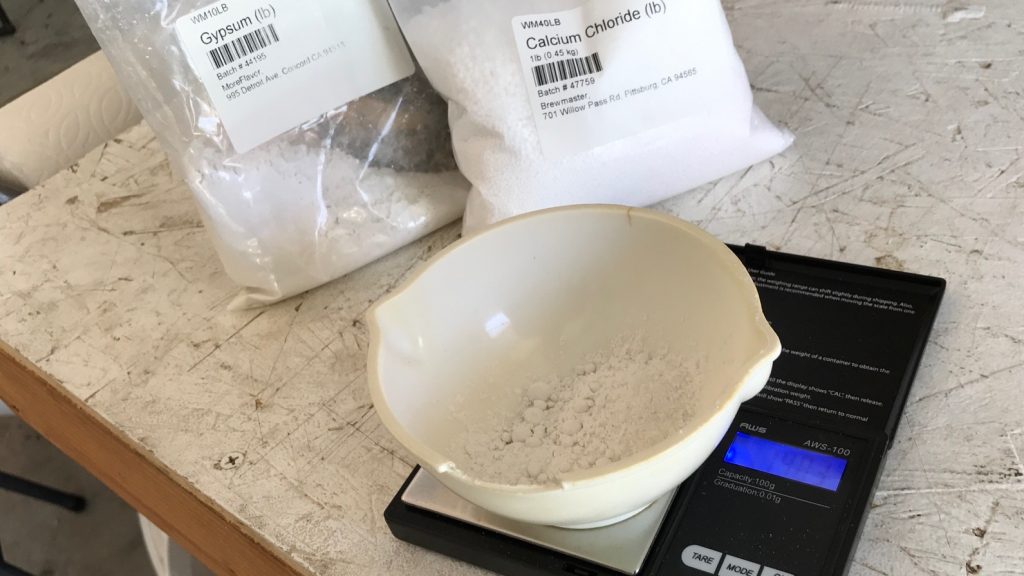

I adjusted the water to my desired profile using gypsum, calcium chloride, and lactic acid.

Finally, I dropped my heat stick into the water and set a timer for it to turn on early the next morning.

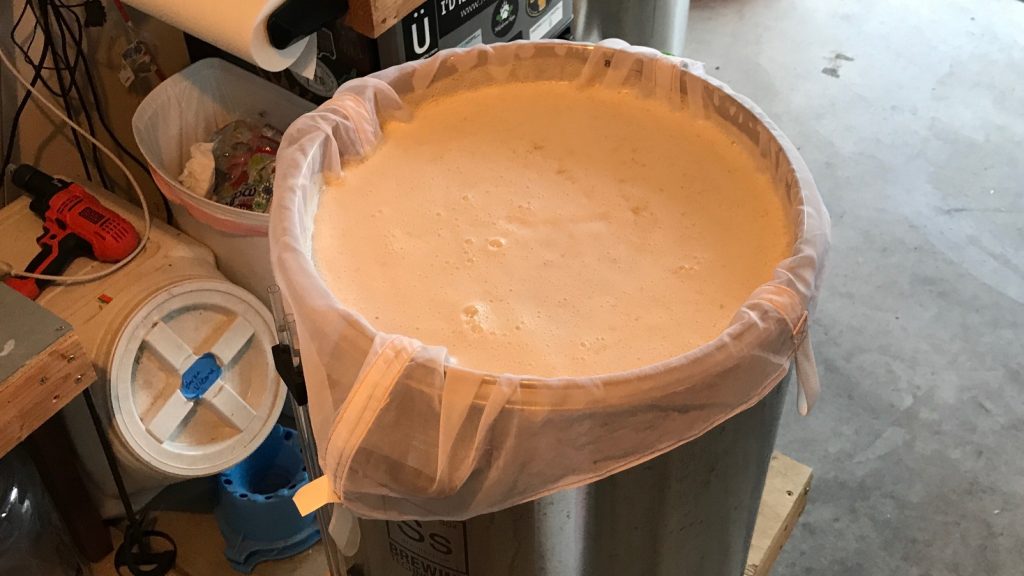

I awoke the following morning to water that required mere minutes to reach strike temperature, at which point I stirred in the grist, nearly topping out my 20 gallon mash tun.

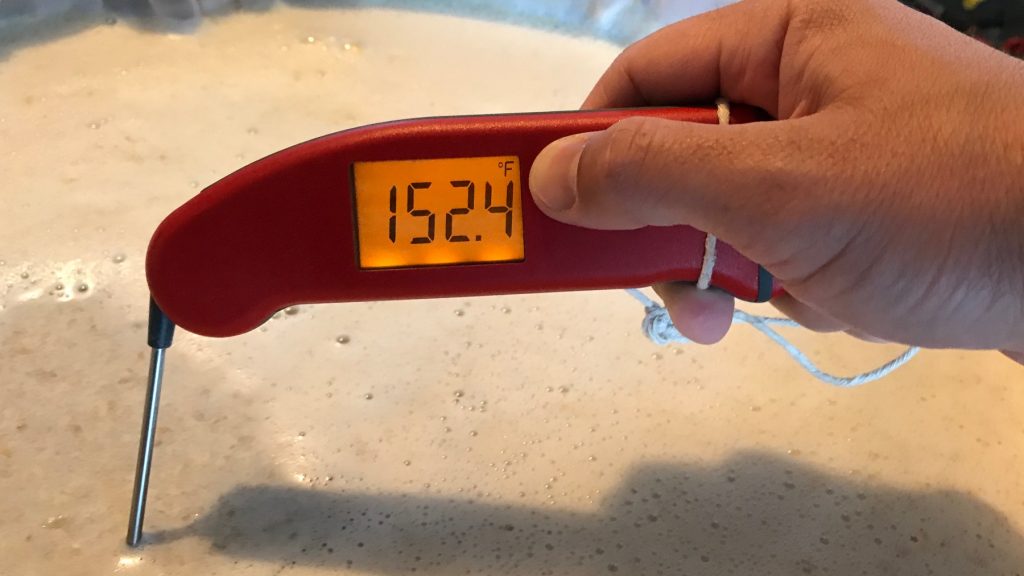

Once fully incorporated, I checked to confirm I’d hit my target mash temperature.

A check of the pH 15 minutes into the mash confirmed the prediction made by the Bru’n Water Spreadsheet.

With a few minutes left in the mash, I measured out 2 sets of the same amount of hops, one for each condition.

The hops for the first wort hop batch were placed in one kettle.

When the 60 minute mash rest was completed, I began collecting the sweet wort.

The entire volume of sweet wort was initially placed in an empty kettle where I gently stirred to ensure homogeneity before transferring half to the kettle containing the first wort hop addition. I lit the flame under the first wort hop kettle first, allowing it to come to a boil before proceeding with the batch that would receive a standard 60 minute bittering addition.

Once the second batch reached a boil, I poured in the single hop addition.

The worts were boiled for an hour after which I quickly chilled each to slightly warmer than my groundwater temperature.

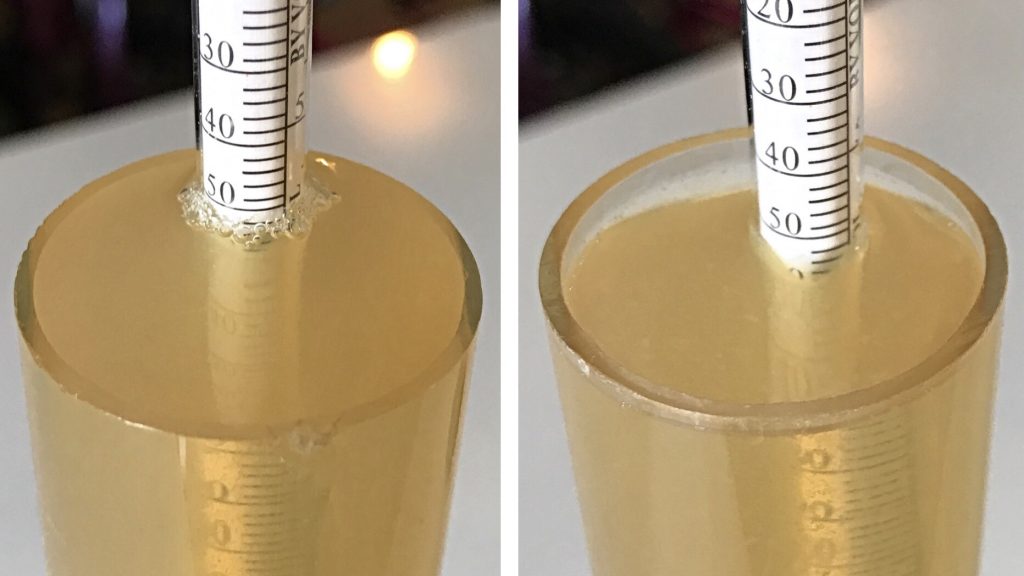

Hydrometer measurements at this point revealed both were sitting at the same predicted OG.

Each batch of wort was racked to separate identical fermentors.

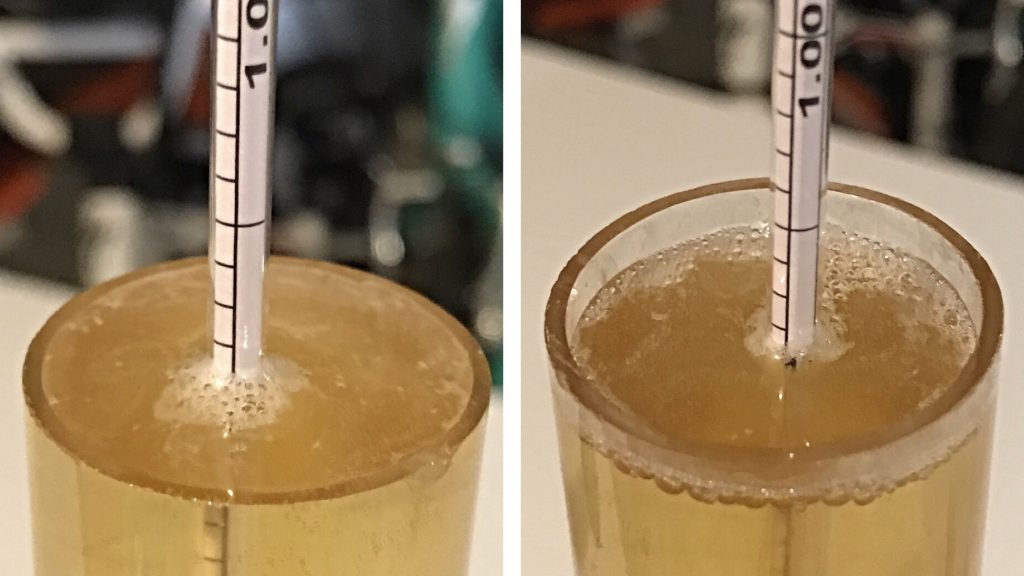

I placed the the Brew Buckets in my fermentation chamber and left them alone to finish chilling. Approximately 6 hours later, both worts had stabilized at my desired fermentation temperature of 50°F/10°C, so split the yeast evenly between the batches. At 12 days post-pitch, fermentation activity nearly absent, I bumped the controller to 60°F/16°C to encourage complete attenuation and clean up of any off-flavors. The beers were left alone for another week before I took hydrometer measurments confirming FG had been reached in both.

I knocked the temperature down to 32°F/0°C for cold crashing, fined with gelatin, racked the beer to kegs, then placed both in my keezer to lager for an additional 2 weeks while carbonating. When it came time to collect data, they looked similarly clear and bubbly.

| RESULTS |

A total of 21 people of varying levels of experience participated in this xBmt. Each participant was served 1 sample of the first wort hop beer and 2 samples of the beer made with a standard 60 minute bittering addition then asked to identify the sample that was unique. Given the sample size, 12 tasters (p<0.05) would have had to select the unique sample to reach statistical significance, though only 7 (p=0.58) made the correct selection, exactly the amount expected by random guessing alone. These results suggest participants were unable to reliably distinguish a beer made with the first wort hop method from one made with a standard 60 minute bittering addition.

Lab Data

Curious as to impact first wort hopping had on bitterness level, I sent samples of each beer to Oregon Brew Lab for IBU analysis, something we didn’t do in the first iteration of this xBmt. While I wasn’t convinced the predicted IBU would perfectly match lab measurements, I have to admit I was pretty shocked with the ultimate discrepancy, even considering the ±0.5 margin of error.

Curious as to impact first wort hopping had on bitterness level, I sent samples of each beer to Oregon Brew Lab for IBU analysis, something we didn’t do in the first iteration of this xBmt. While I wasn’t convinced the predicted IBU would perfectly match lab measurements, I have to admit I was pretty shocked with the ultimate discrepancy, even considering the ±0.5 margin of error.

| Tinseth Formula | Rager Formula | Garetz Formula | Measured | |

| First Wort Hop | 25.6 | 30.6 | 25.6 | 15.5 |

| 60 Minute | 23.3 | 27.8 | 23.3 | 13.5 |

My Impressions: Out of the 6 blind triangle tests I attempted, all of which I fully admit boiled down to me simply guessing which sample was different, I was correct twice. I didn’t perceive either beer as being characteristically different than the other in terms of bitterness quality, aroma, flavor, or mouthfeel. While both were very clean and surprisingly crushable, they possessed a character I’ve come to expect in beers brewed with a large portion of Weyermann’s Barke malts, a flavor reminiscent of white grape skin. Not offensive by any means, in fact my neighbors couldn’t get enough of this beer, but definitely not my preference… I won’t be upset once I’ve used up all the Barke malt in my brewery.

| DISCUSSION |

As Stan Hieronymus discusses in his recently published article, brewers have been lauding the practice of first wort hopping for its ability to impart a qualitatively different bitterness while also retaining unique aromatic characteristics that are expressed in the finished beer. Given the wonderful accounts from trusted authorities, professional and homebrewers naturally began adopting the method, ultimately producing even more reports of the benefits of first wort hopping as compared to standard 60 minute bittering additions. I’m reminded of a saying:

The plural of anecdote is not data.

Humans are a curious lot, born with incredible perceptual abilities, though forced to rely on idiosyncratic interpretations of that which enters our perceptual organs. Given the flimsiness of system, what we sense is often biased by expectation, which is hugely influenced by those we view as trustworthy. I can’t help but consider this reality when it comes to first wort hopping, a method seemingly built only of anecdote and conjecture. With nothing more than hypothesis as to how adding hops to wort prior to boiling actually impacts beer characteristics, the results of this xBmt along with findings from various other experiments leave me even more convinced the only benefit to first wort hopping is that it reduces the likelihood of a boil over. This, admittedly, is the only reason I’ll continue doing it.

The most interesting thing about these findings to me is the discrepancy between the predicted IBU in BeerSmith and the lab measurements showing that regardless of the formula used, the actual bitterness was nearly 10 IBU less than expected. While I’m not convinced the IBU is necessarily a lie, the commonly used formulas certainly would seem to be a less-than-accurate measure of a beer’s actual bitterness.

If you have thoughts about this xBmt, please share them in the comments section below!

Support Brülosophy In Style!

All designs are available in various colors and sizes on Amazon!

Follow Brülosophy on:

FACEBOOK | TWITTER | INSTAGRAM

If you enjoy this stuff and feel compelled to support Brulosophy.com, please check out the Support Us page for details on how you can very easily do so. Thanks!

35 thoughts on “exBEERiment | First Wort Hop vs. 60 Minute Addition In A German Helles Exportbier”

someone on HBT said FWHing was developed by german brewers to decrease hop aroma and increase utilization. never followed up on that, but it sounds possible i guess. you might consider getting the IBUs tested on a few more batches that should be identical to see what the “method” variability is.

As your BeerSmith figs and the lab figs show, first wort hopping does appear to give slightly better utlilization – about 10% better in your figs and 15% better in the lab figs. For a low IBU beer that’s imperceptible but it might be perceptible in beers over 40 IBU. Not necessarily a different kind of bitterness – probably just a slight increase in bitterness (and possible cost saving to a brewery).

Besides that and boilover mitigation, FWH does appear to be pointless.

I understand that IBU calculation in Beersmith are made for ideal conditions. You usually don’t use the real value of AA at a given moment. The measurements on the other hand take in account the effect of hop age and storage.

I’d like to see this experiment redone with a Smash Pale, where the bitterness difference would be perceptible against the fruity/floralness of the late hope additions.

I have found IBUs to be dependent on pitching rate. I postulate that hop alpha acids stick to the walls of yeast. When trying for a high IBU beer I under pitch slightly.

You might actually have a point there, this sounds just like the follow up xbmt on the topic.

Does anybody here knows someone on a lab that might be able to shed a light on it?

Were the hops from a sealed, purged bag? Maybe they were somewhat aged & lost some IBU’s?

I’d opened the sealed YVH bag the day before Brewing and put them in a vacuum sealed bag.

Interesting result. I’ve never had a beer tested, but now I’m curious. I’ve definitely had micro’s (local) that were too bland–had no discernible bitterness–and thought “man, I wish they had a lab”. But with homebrew, I’ve never had one that was undrinkably bland. I guess I wouldn’t be afraid to double the bittering hops from now on.

What about perception/preference both yours and the atendees ? What was taster?

I suspect the AA of your hops had significantly dropped flrom date of initial test to the date you used them, and the reason for your low IBU results are more to do with that than the formulas. Do you have additional hops you could send in to be tested? Not sure if Dana tests that or not…but others do. Would be interesting to see if this hypothesis is correct…

The measurements kind of fall in the same range as the EB when you consider the anecdotal data-brewers that chill slowly match the IBU prediction vs. fast chillers are significantly lower than predicted. It does make me wonder about recommendations brewers have made where they specify IBU’s vs. amounts of hops for recipes.

Question: What is “white grape skin”? Is this similar to green grape skin? An effort to make grapes great again?

Any thoughts on the purported foam positive effect of FWH? Looking at the pics above, it doesn’t seem to have made a big difference. 60 minutes may be better, but it’s hard to tell if thats just related to how the beer was poured, etc.

If the IBUs are so far off the calculated values, what’s the point of the calculators? Have any of the calculators come close to measured values for…. any beer making metrics? They all seem to be way off to me in these experiments to date. Perhaps their value is – better than doing nothing and for recipe replication? I don’t feel so bad about winging it for 20 years now.

Definitely check out Denny’s article, “The IBU is a lie”. The equations were all determined experimentally, and based on the brewing method of whoever came up with it. No one bothered factoring in chilling time in these equations, which probably wouldn’t be terribly hard to do now. If Denny and Drew had the chilling time to 175 F for their experiment, they could probably come up with a fudge factor.

Don’t quote me on this, but I believe the Tinseth formula was created using a much slower cooling method than what most people use today. So his hops were in hot wort for longer than what most of us do now, thus the higher calculated value.

On Denny and Drew’s podcast where they analyzed the IBUs from several different batches and compared them to lab values, the guy that was closest to the calculated value was also one that took a relatively long time to cool his wort (I can’t remember how long it took him.)

Yup.

Glenn Tinseth was a homebrewer in the 1990s. I don’t know if he brews anymore.

Tinseth actually used whole hops to make his formula. So the 10% thing for pellets vs. whole hops actually goes the other way around than people think.

Tinseth also used a much slower chill method, not a copper coil. The formula will work better for those who do no-chill or chill by immersion in a cold water bath.

Brulosophy might want to run the xbmt again with whole hops and slow chill. Or maybe not. I would find it interesting.

This reminded me, someone at the AHA forum posted the “Diversity method” for IBU calculation by Petr Novotný. I don’t know exactly how it’s calculated, but there’s some posts on it (In Czech). There’s a calculator on homebrewmap.com, when I use the values provided I come up with 18.2 IBUs for the FWH beer. I could be off, I guess at some of the times (15 minutes FWH to boil w/80 g, 60 minute boil-FWH hops left in, 15 minute whirlpool w/FWH left in). The extra time for the FWH is expected to add 4.7 IBU, so a little off using my estimated numbers, but pretty accurate. Links to the calculator and the AHA forum post. I might start doublechecking all my brews with this.

https://www.homebrewmap.com/en/tools/calculators/ibu-diversity

https://www.homebrewersassociation.org/forum/index.php?topic=30046.msg394530#msg394530

I might also be an idiot that can’t operate the internet correctly. I think I should have gotten 26 IBU for the FWH beer. I’ll put my dunce cap on and go sit in the corner.

Hop utilisation begins around 80 Celsius and its that extra contact time over 80 before the start of the boil that gives the FWH version the extra IBUs that were measured.

I wonder how a beer would turn out if the bittering addition was not boiled at all. Rather a very long (3 to 5 hour) steep at 90 Celsius, then removal of the hops and a standard boil.

For me the take away is that I will start FWH of all of my beers. The mitigation of boil over alone is worth the implementation of the practice. Perhaps a more interesting take away is that the IBUs are lower than expected. I have suspected for some time that BS and BF are not able to accurately calculate the early addition IBUs accurately for home brew. (although I do not doubt the efficacy of their methodology or of their formula) Far too often the hops we use as home brewers are simply aged, and or exposed to oxygen. I have been bumping the bittering IBUs from early additions up by 20% in an effort to gain the desired results.

Kudos to you for running this experiment again! The willingness to run non-sexy experiments like this seems to me to say everything that needs to be said about the noble purpose of this site.

IBU calculators predict IBUs of the wort before pitching the yeast, not in the final beer. As Colin Kaminski hints at above; it is generally understood that adding yeast drops the IBUs. It isn’t surprising that the lab measurement on the finished beer was lower than the predicted value for the pre-fermentation wort.

Thanks for the experiments!

I was so excited when I saw the header that I might find out if FWH made a difference in the smoothness of bittering COMPOUNDS, and you use the most mellow hop on the planet! I’m so confused why you didn’t use something with cohumulone over 35% to see if it does smooth it out. Might you do this with Chinook?

Have you tryed to FHW through a hop rocket /hopback what kind of difference would this make ?

sorry i should add that i mean these hops wouldnt be boiled at all, just removed from the boil, but the wort would still be boiled as normal.

I’m just wondering whether the result given by the tasters was biased by the hops selected for this xBmt.

Mittelfrueh is known for its noble aroma that is far from being bold.

It would be interesting to repeat the experiment by using a more assertive hops to understand whether FWH may result in a detectable aroma difference of the beer brewed with this technique.

Maybe Mittelfrueh was too subtle to reach this goal…

I’ve seen this disparity between calculated IBUs and lab values a number of times over the years. The equations are not very good predictors. Also, if you try to account for hop aging, those equations are even more uncertain!

I’ll stick with ballpark estimates: ounces x alpha x 4 (for 60 minutes, 5 gallon batch). Or maybe better yet: the old HBU method.

Thanks for the time/effort on this one. Regarding the FWH portion of this experiment, how long did it take for the FWH pre-boil batch to come to a boil?

I’m just thinking there could be some difference between FWH taking 5 min to boil (65min bittering, essentially) vs 15 min to boil (75min bittering). If someone takes 15 min to get their FWH batch to boil, they could easily say “well, I MYSELF notices a difference.”

Average time to get to a boil after the mash is about 15-20 minutes depending on outside temp.

do an experiment on the effects of boil pH and lab tested IBU. After all, we know pH affects isomerization; test it.

I wonder if the the no-sparge method might be influencing the results a bit here? Presumably contact time for FWH would be significantly longer if you were sparging. It is possible that an extra hr of sitting in the first runnings at like 150°F could have an effect that is not captured by this exbeeriment. In those situations I would expect sparged FWH to have higher IBUs.

I generally agree that FWH probably do not make the beer “finer”. When I use software to estimate IBUs, I just estimate them FWH as boil additions. However, an additional, non-scientific reason to FWH is the aroma while sparging..mmmmm.. nothing better!

Very cool experiment, but based on listening to the podcast and these results, since the American style FWH addition didnt change perception of the beer, why not do a beer combining the American and German style FWH style. 1 beer gets all buttering hops + 30% of the late addition before the boil, and the other gets the normal hop schedule. The German study sounded like they received great results so I can’t wait to see what your team comes up with next!

is there any differencies between the tastes? thank you anyway really interested in those topics

Great experiment, thanks for the receipe, this blog is very full of informations

Interesting experiment! Your thorough approach and curiosity make for a compelling read.

Unissula