Author: Marshall Schott

We recently published the 150th exBEERiment article, which is crazy to think considering all that’s involved in each one. For some perspective, this roughly amounts to:

- 150 individual brew days

- 1,500 gallons of beer

- 3,000 survey responses

- 4,000 hours of writing/editing

Looking at it this way, I can’t help but question my own sanity a little bit. When I started this series, unlike many seem to think, my intent was never to disprove anything, but rather explore and learn more about the methods used to make beer. In fact, I distinctly recall thinking my findings might be used to buttress the claims of certainty I’d been regurgitating in online forums and at homebrew club meetings.

That wasn’t really how things panned out. In fact, of the 36 xBmts we performed in the first year after integrating the triangle test, only 8 returned statistically significant results, and strikingly, they didn’t include many of the variables most expected to make a difference. This seemed to create a spectrum onto which people who read the xBmt articles tended to fall, a continuum that remains to this day. On one extreme are those who view the lack of significant findings as a sign that our methodology is in some way, or many ways, flawed. The most ardent in this camp contend our participants’ palates aren’t advanced enough to decipher the differences, the triangle test isn’t sophisticated enough of a measuring tool, or that we’re just not good enough brewers to make the impact of the variable stand out. On the other extreme lie those who seemingly view every result we publish as gospel, proof that the methods of yore are utter hogwash that no longer need to be used.

I could write a dissertation in response to either side, point out how confirmation bias is likely hugely responsible for both sentiments, and proceed to defend our approach. But that’s not why I’m here today. Rather, I’ve noticed a string that ties both sides together, albeit with a slightly different impetus, is this idea that our xBmts are demonstrating that…

Nothing matters!

Some say it because they think it’s funny, others because they’re nihilists, and still others as a way to question the results and/or our methodology. The apparent commonality between them all is the belief our xBmts don’t return “any” significant results, a complete misunderstanding that I hope to address in this overview.

The Big Picture

Of the 150 xBmts we’ve performed, 140 have relied on the triangle test to determine whether participants were capable of distinguishing a beer brewed one way from a similar beer brewed with something different to a reliable degree. The triangle test cannot provide any evidence as to whether a variable had an objectively measurable impact on a beer, but rather can only demonstrate whether a variable made such a difference that tasters were able to tell it apart to a significant degree when relying on a specific threshold, which for us is a p-value of 0.05. To put it simply, the triangle test doesn’t allows us to say with any confidence whether a variable impacts a beer, only whether tasters are capable of tasting that impact.

As humans, we have a tendency to notice and recall those things that are most surprising while sort of ignoring the things we expect to see or that don’t make us go “huh?” Take, for example, the fact people claim “nothing matters” despite 45 of the 140 xBmts (32.1%) utilizing the triangle test have returned significant results. Indeed, many of the variables believed to matter most aren’t among those on this list, which is shocking not just to readers, but to us as well. Unfortunately, this seems to have led to many sweeping fascinating findings under the rug. Let’s have a look, shall we?

What Does and Doesn’t Matter?

The title is tongue-in-cheek, a riff on the theme of this article, I’m not suggesting the variables discussed in this section actually do or don’t matter. It’s all good. In this section, I’ll go over some of the xBmt variables we’ve focused on most that have produced some of the more interesting results.

Yeast Pitch Rate

Since April 2015, we’ve performed 6 xBmts focused on yeast pitch rate, all of which we expected to return significant results, yet only the one comparing ale to lager pitch rates in a Kölsch did. A beer fermented with a single vial wasn’t noticeably different than one fermented with a yeast starter, tasters couldn’t tell apart a beer that was underpitched from one that was overpitched, and pitching a dry yeast starter produced a beer that was generally indistinguishable from one fermented with rehydrated dry yeast. Is this proof that pitch rate doesn’t matter? I don’t think so, which is evident in the fact I still rely on yeast starters when I brew. Do some people worry about pitch rates more than they have to? I guess that’s ultimately up to each individual brewer, but yeah, I think some people maybe take it perhaps a tad more seriously than they need to.

A change I have made is that I rarely rely on pitch rate calculators these days but rather stir up a starter based simply on volume, and it’s been working just fine. Modern yeast cultures are massively more viable than they used to be, which I have to believe is where the focus on pitch rates stemmed from. It’s not that pitch rate doesn’t matter, but rather the yeast we’re using today is so far ahead of where it used to be in terms of overall health. At least that’s how I see it.

One cool thing that came out of the yeast pitch rate xBmts is what we’ve come to refer to as vitality starters, which involves spinning yeast in about 500 mL of wort for 4 hours prior to pitching. Rather than building up the cell count, the purpose of this method is to ensure maximum vitality so the yeast are rearing and ready to go once pitched. With 2 xBmts returning results showing tasters couldn’t reliably distinguish beers fermented with such a starter from beers fermented with standard starters, I’ve become a huge fan of vitality starters and have heard from many people who are successfully using them regularly in their brewing.

Fermentation Temperature

Without a doubt, our fermentation temperature xBmts have led to the most head scratching, confusion, questioning, and whatever else people do when they’re shocked. It’s commonly accepted that yeast of all types produce different compounds when fermented at temperature differences as small as 2°F/1°C, and that at the very least, the temperature during fermentation ought to be controlled to within a specific range.

Crazily, out of over 8 xBmts using myriad yeast strains, only 2 have come back significant, and in both of those the temperatures were pushed to the extreme. Tasters have been otherwise unable to reliably distinguish between beers fermented at drastically different temperatures using WLP029 German Ale/Kölsch, WLP800 Pilsner Lager, Saflager W-34/70, Southern Hills Frankenyeast Blend, and Wyeast 2124 Bohemian Lager yeasts. Moreover, an xBmt focused on temperature stability also returned non-significant results, suggesting variability in temperature during fermentation may not be detrimental.

We’ve primarily focused on lager yeasts when exploring fermentation temperature, partially because we all love lager, but also because I think we expected such strains to easily produce a difference. The fact that hasn’t been the case has certainly caused me to question what I once believed to be true about lager yeasts, to the point I now often ferment personal batches of lager just like I do ale, even bypassing the quick lager method I once swore by.

Speaking of, the quick lager method is a variable I plan to circle back around to sooner than later, as the significant results from the xBmt comparing it to a standard lager fermentation was quite bemusing. Without making excuses, as I’m okay if it does produce a beer with different character than traditional lager fermentation, I was unfamiliar with the yeast used and can’t help but wonder how things will pan out using strains I’ve more experience with.

Water Chemistry

It’s so weird for me to think that just a couple years ago, I claimed in a friendly argument with another brewer that water chemistry was of minor importance, contending that people likely wouldn’t be able to taste a difference between a beer with a defined profile and one where the water was left alone. Could I have been more wrong?

When it comes to water chemistry, the 2 general components are mineral content and pH, both of which we’ve performed multiple xBmts that have yielded fascinating results. Most curious to me has been the evidence suggesting mash pH out of the typically accepted range doesn’t seem to have nearly the impact on efficiency, aroma, or flavor as expected. On the other hand, multiple xBmts have demonstrated how differences in mineral content tend to produce perceptible differences in the finished beer.

Boil Length

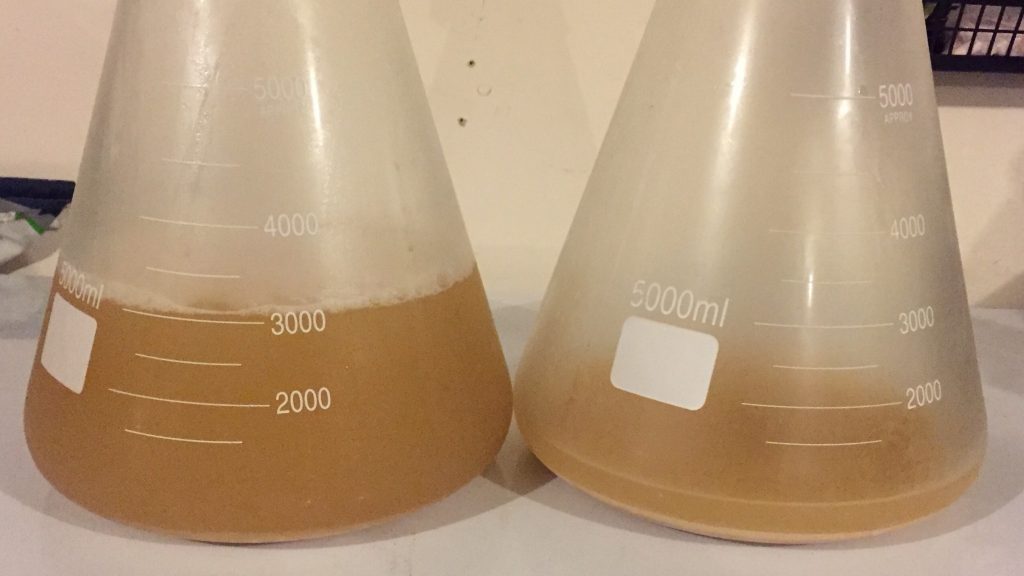

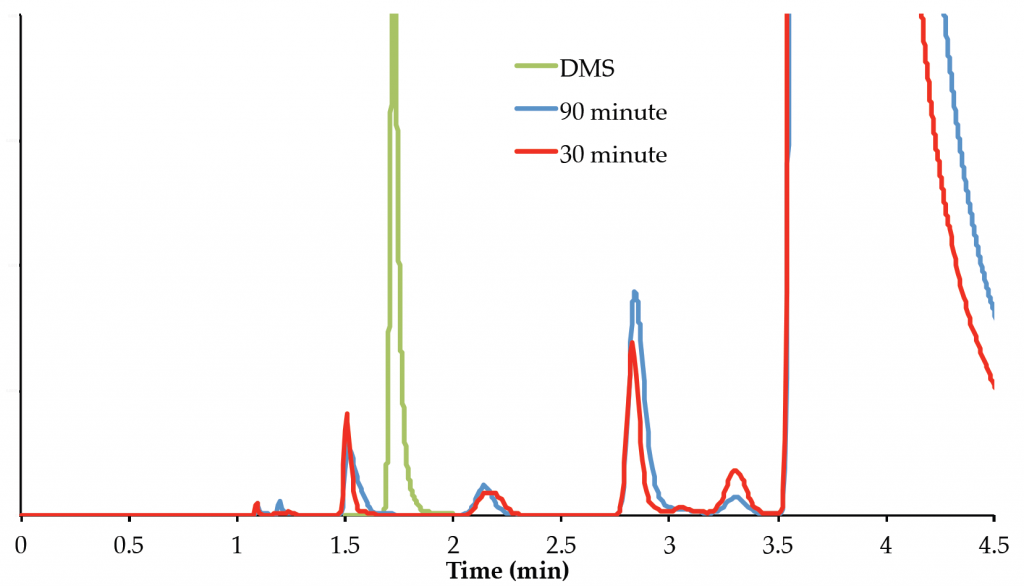

In brewing, the boil serves various purposes including the coagulation of proteins (hot break) that settle out into trub, isomerization of alpha acids from hops, and volatilization of DMS/SMM. The standard accepted by most brewers is to boil wort for no less than 60 minutes with many believing it necessary to extend the boil to 90 minutes or longer for wort made with a large portion of Pilsner malt, the failure to do so all but ensuring a beer chock full of creamed corn nastiness. To test this claim out, we performed 2 xBmts, one using standard Pale 2-row malt boiled for 30 or 60 minutes and the other using a Pilsner malt wort boiled for either 30 or 90 minutes. The results from both, to the surprise of many, were non-significant, meaning tasters were unable to reliably distinguish the short boiled beers from the those boiled longer.

Curious whether this was an issue with participants’ bad palates, I sent samples of the finished beers from the Pilsner malt xBmt to a lab for DMS testing and learned the 30 minute boil beer had the same level of DMS as the 90 minute boil beer… which was precisely none.

In a follow-up xBmt, we compared beers produced using either a vigorous or weak boil and, yet again, tasters couldn’t reliably tell them apart. Testing the extreme, we designed an xBmt to test how a batch of Berliner Weisse produced without a boil would compare to a batch produced with a 45 minute boil. Finally, a significant result. In fact, based on the p-value (0.0000000004), this was one of the “most significant” xBmts to date, suggesting boiling does matter, though perhaps due to advancements in malting and a greater understanding of brewing, boil length may not be set in stone.

Gelatin

Filtration in general has traditionally been viewed as a stripper of delicate aroma and flavor in the craft beer and homebrewing worlds, with some proudly proclaiming their skipping of this step as a way to prove how craft-y they are. While mechanical filtration hasn’t really seemed to catch on in homebrewing, fining with chemicals to reduce clarification time is quite popular, particularly super cheap and easy to use gelatin. The hypothesis that fining with such an aid reduces desirable characteristics in beer seems to make sense, as the haze causing particulate being pulled out by the gelatin ostensibly possesses aromatic and flavor compounds. We wondered if the sacrifice was worth the reward of clear beer and put it to the test with startling results. Participants were unable to reliably distinguish a gelatin fined Pale Ale from the same beer that was not fined, even though they looked drastically different.

I’m compelled to believe what makes wrapping one’s mind around these results so difficult is the fact gelatin and other fining agents absolutely do remove stuff from beer, it can very easily be observed, stuff presumed to contribute to the overall quality of the beer, yet people can’t seem to tell a difference.

As a lover of clear beer, I look forward to exploring the impact using an actual filter has by comparing it to unfiltered beer as well as various other fining agents. Until then, I’m sticking with gelatin, which many of us have come to refer to as “powdered time,” as it seems to do in mere hours what many wait weeks for.

Fermentation Vessel

We receive xBmt suggestions all the time with most being added to a list that we pluck from when the time comes. If ever I received a groaner of a suggestion, certain it would return a non-significant result, it would have to be the many asking us to compare different types of fermentation vessels. We spend all this time (and money) adjusting our water profile, making clean wort, boiling it, adding hops at precise moments, quickly chilling it, pitching a bunch of healthy yeast, then fermenting it in a well-controlled environment. Surely, the type of vessel its fermented in wouldn’t matter. Would it?

When the first fermentation vessel xBmt comparing beers fermented in either a plastic bucket or PET carboy came back significant, I was convinced it had to do with the low sample size of only 10 participants. False positives happen, whatever, we’ll readdress the variable later. For the second xBmt comparing a PET carboy to a glass carboy, I had 25 blind participants take the survey and the results were again significant. Assuming the noticeable differences were caused by oxygen, I compared beers fermented in either a stainless Brew Bucket or a glass carboy, and sure enough, people were unable to reliably distinguish them.

I was convinced oxygen was at play and thus confident an xBmt comparing a beer fermented in a glass carboy to one fermented in a corny keg would return non-significant results. But I was wrong, tasters could tell them apart. Could it be an issue of fermentor dimension? We have more fermentation vessel xBmts planned to test it out!

On Participant Preferences

Without fail, and regardless of whether the results are significant or not, there’s one question we receive after publishing every xBmt article:

Which one did people like the most?

I am adamantly convinced preference is wholly subjective, that what someone else perceives as best might be what another person experiences as just okay. Even in competitions and judging where a beer is compared to a standard, personal opinion is going to have an influence, there’s no way it can’t, because we’re not robots. Hence my position on this question– I fucking hate it. I hate the thought of people changing what they do because of the expressed preference of others. It’s possible I’m in the minority on this issue, which is why we continue to include such data in xBmt articles that have reached significance, sharing only the preferences of those participants who were correct on the triangle test. The findings have rarely been conclusive.

Since it’d be laborious to go over the preference results from every significant xBmt, I’ve opted to cover a few from the aforementioned results, which happen to be quite interesting.

Fermentation Temperature

While we didn’t collect preference data in the WLP002 English Ale fermentation temperature xBmt, I thought it was pretty fascinating that of the 12 participants who were correct on the triangle test, 8 believed the beer fermented warm (76°F/24°C) was the one fermented cool (66°F/19°C). I’m not sure what, if anything, can be gleaned from this.

Out of the 12 of 21 blind tasters who were able to distinguish a beer fermented with Saflager W-34/70 at 60˚F/16˚C from the same beer fermented at 82˚F/28˚C, 7 selected the warm ferment beer as their preferred, 2 chose the cool ferment sample, 2 felt there was a difference but had no preference, and 1 thought there was no difference. This doesn’t mean the warm ferment lager was necessarily better, just that of the participants who were correct, a majority liked it more than the cool fermented sample.

Fermentation Vessel

Again, we hadn’t started collecting preference data at the point of the xBmt comparing a plastic bucket to a PET carboy, though we were when 14 out of 25 participants correctly distinguished a beer fermented in a glass carboy from one fermented in a PET carboy. That result was surprising by itself, but the fact 10 of those 14 tasters reported preferring the beer fermented in glass had me floored and really made me consider what it could be that was causing this difference. In a follow-up xBmt comparing a glass carboy to a stainless keg, preference ratings seemed to return to the norm with 6 of the 16 correct tasters preferring the carboy fermented beer, 3 saying they liked the keg fermented beer more, 3 endorsing no preference despite noticing a difference, and 4 reporting they noticed no difference.

Water Chemistry

In an xBmt comparing a beer made with brewing water built to a specific profile to one brewed with filtered tap water, 7 out of 8 correct participants reported a preference for the flavor of the former. Interestingly, preference ratings for Dry Stout made with either “Pale Hoppy” or “Dark Malty” water profiles were split essentially down the middle. When a couple Belgian Pale Ales were adjusted to different sulfate to chloride ratios post-fermentation, half of the tasters who were correct on the triangle test reported preferring the high sulfate beer while only 2 liked the high chloride sample more. This made me wonder the extent to which preference is a function of expectation, for example, since IPA is (or at least used to be) expected to be crisp and dry, people might prefer one made with higher sulfate content. I questioned this hypothesis after participant preferences were equal between a MACC IPA brewed with a 150:50 sulfate to chloride and the same beer brewed with a 50:150 ratio.

The Significance of Non-Significance

Publishing a non-significant xBmt result, particularly when the variable is one presumed to be of massive importance, inevitably leads to a few folks quickly pointing out how the results don’t “prove” anything but are merely inconclusive. Sure, and as we’ve alluded to a gazillion times, one result does not a principle make, whether significant or not.

However, as much I appreciate and mostly agree with this sentiment, I feel like it sort of ignores the concept that an absence of evidence is, or starts to become over time, evidence in itself. If we look at something big like lager fermentation temperature where all but 1 xBmt, which arguably tested an extreme, has returned non-significant results, that seems at least somewhat meaningful. But rather than accepting it for what it is, some people misconstrue this as us claiming fermentation temperature doesn’t matter. That’s not at all true! At best, what we can say is that we haven’t been able to produce a large enough difference such that participants are able to reliably distinguish between lagers fermented cool and warm, or boiled for 30 and 90 minutes, or mashed high and low. We’re certainly not naive enough to believe this “proves” these things don’t matter. Maybe modernization has mitigated the necessity of old techniques, but even so, it’s not our place to tell you how to brew or what to like. Not convinced by an xBmt result? Cool. Want to test it out for yourself? Even cooler!

CONCLUSIONS

Homebrewing is evolving. Like most hobbies, many who get involved end up entrenched, which spurs thinking, experimentation, and ultimately the revelation of new information. For those who have spent years studying classic brewing texts and relying on traditional methods to craft what I trust are quality beers, this can be kind of threatening, a crack in the illusion of certainty held about something one is passionate about. Prior to starting the exBEERiment series, it never dawned on me that brewers might be so married to their approach that findings calling them into question would cause such a stir. The feedback we’ve received over the last 150 xBmts has been a real eye opener, some people really are invested in their way of doing things, and I appreciate that. At the same time, I continue to find very valuable the ongoing search to learn more about brewing beer and look forward to the next 150 xBmts!

Support Brülosophy In Style!

All designs are available in various colors and sizes on Amazon!

Follow Brülosophy on:

FACEBOOK | TWITTER | INSTAGRAM

If you enjoy this stuff and feel compelled to support Brulosophy.com, please check out the Support Us page for details on how you can very easily do so. Thanks!

38 thoughts on “Nothing Matters! | Reviewing The First 150 exBEERiments”

I stumbled across your page while attempting to google research some of the same topics you have addressed in your exBEERiments and have found them to be most useful and a go-to reference when I’m looking to glean brewing wisdom, chiefly because I do not have the time, money, equipment (and sometimes patience) to conduct similar experiments. They’ve helped me adjust my own brewing and (in my opinion) made me a better brewer.

Most illuminating. Nothing Matters has given me more confidence to go forward with my own methods. I have been reading xbmt results for a while now and really like it when my own conclusions from my small home brew experience seem to mirror the results or at least confirm my thoughts on the subject being tested. I have am a fan of lager and have adopted the quick method with pleasing results. Tonight I tasted my first IPA fined with gelatine and I could see the future looking through its amber goodness! I use a 20 litre Braumeister and a pair of SS brew tech chronicals,(I won one at a conference), each in their own temp controlled fridge. I am now at a point where I’m wondering how I can determine the profile of my water supply and then make any adjustments I might need to underpin the styles of beer I’m attempting to emulate. Waffling a bit now so I’ll just say thanks for the site and info and good luck to you.

Generally, your local water provider should be able to provide you a water profile. Here in colorado springs, our provider publishes a semi-annual report of their profiles, complete with the average content from the last 6mo as well as standard deviation. If you can’t get the profile report from your water provider, you can always send a sample to a water testing facility found online. A quick search will result in a company who does a complete profile for less than $30. Just understand that the latter method gives you the profile for that one time and things do vary. If you want total control of water you can start with distilled water or purchase a reverse-osmosis filter to start with water that has nothing in it and build your profile from there.

I’d be interested in any recipes you have for the 20l bm. Are you a sparser?

Great post. When you think that beer has been brewed for 3000+ years and most of the methods we take for granted to produce great beer have only been around for only a small portion of that I think it proves the point that nothing matters so relax and don’t overthink it. There probable are valid reasons these practices came into play over the years but I think an individual homebrewer has to decide what does and doesn’t make a difference to them. I know that vacuum packing hops according to your xbnts doesn’t make that much of a difference but it makes me feel better to vacuum pack the hops I don’t use so I will probably continue doing that.

It really comes down to you are brewing for yourself and to make beer that tastes good to you. I really don’t buy the “oh you have to develop your palette” bullshit.

I have really enjoyed your articles over the years and when I get “analysis paralysis” come to this site to just calm down, relax, and make good beer. Please keep up the good work and thanks to all of you for the dedication you put into the hobby.

Yes – when you consider that medieval monks and 16th century Belgian farmwives could make good beer – we with fully modified grain and super yeast should be able to do it quite easily – and you have shown that we can. Thanks Marshall and crew!

Excellent stuff.

I’ve been brewing for about 4 years and, despite the notion that so many of the things I do don’t really matter in the end, I still practice them as if they do; Perfect fermentation temperature, boil length, pitch rates, chill rates; they are all still important to me despite the lack of evidence. I admit I don’t worry as much over those variables, thanks to you guys, but I still practice them as if they were gospel.

One BIG change that I’ve made was exploring the world lagers. They were always out of reach because I didn’t want to tie up my damn chamber for a month. THANK YOU!

But I wonder: After all these forays into nihilism, what changes have you made to your foundational brewing practices? What do you do different on brewday?

I’d add the short and shoddy vs traditional experiment to your list of experiments that looked at temperature control. Would like to see more experiments on this variable with ale yeasts.

First off let me say that I love your site and appreciate all the fun you are having with it. I can say that you changed my brewing days by countless variables. Also as far as fermentation temperature is concerned. I do have one more variable to try and one that has affected my brewing in the early times. Pitching temps. Early in my impatient brewing days I pitched a vial of WLP007 at 90 and cooled it down to 65 over a 36 hour time frame. That beer had a strong banana aroma coming out of the airlock and turned out to be crap. Maybe an exbeeriment pitching an english ale strain at high temps and cooled to pitching temps( over 24 hours) vs one pitched at optimal temps ? Anyway just an idea. Thanks again for all of the work you put in ( even though you are having fun ) and I look forward to your articles weekly !!

It would be interesting to see the fermentation temp. experiment on a large scale, like 10bbls.

I’ve said for a while now that the surfeit of non-significant results suggests that the brewing process is more robust than all the conventional wisdom (do this, don’t do that) might indicate.

That said, I also tend to wonder if there’s a cumulative effect of small differences that ordinarily aren’t perceived individually by most tasters, but if one added all of them together, the differences would be clear.

Sort of like the short-and-shoddy exbeeriment, but more than that.

Fantastic summary. It’s great that you’ve taken a step back to look across all of the work and share observations of what it all means.

One thing I’ve wondered about is instead of asking about preference at the end of triangle tests, how about asking those that correctly identified the different sample to describe how the samples were different?

Keep up the great work!

Love your work. The amount of effort you put into these experiments that you give freely to the community is astounding. If we ever cross paths, you can be sure that drinks are on me.

I’d be interested to see a summary of the results with a less aggressive p value. The p value you choose works really well for large populations or large sample sizes and helps accept or reject experiment results with near certainty. Being that your sample sizes are so small, something as simple as a person with a cold could cause a cross from significant to non-significant with such an aggressive line to cross. The p value that is used in the experiments is very aggressive being that if you extrapolate it out to the general populace it would be ‘most certainly everyone can tell the difference’.

Play around a bit with coin toss or dice experiments and see how often you can get results using completely random data that give ‘the coin is not fair’, or the ‘dice are weighted’ results from small sample sizes. Then keep in mind that one person could have shared some spearmint gum with 3 others before the meeting.

Quite often when I’m reading the results, I will grab less aggressive thresholds for p-values and see if the whole ‘failed to reject the null hypothesis’ dance had a happy ending. I _always_ find the preference information valuable; because, even if the experiment failed to achieve significance knowing that 9/10 prefer it “this way” matters more to me from a brewing standpoint. Especially since having such a small sample size you are probably a victim to confounding variables quite frequently.

Can I second this idea. In fact I think it would be quite interesting to do a survey of the previous result, but look for maybe a 75% CI instead of 95%. I suspect you’ll find quite a few experiments actually do matter, and open up ideas for repeating.

I take the results with a grain of salt. It is a single point in time on a singular system. Has it changed some of my methods? You bet it has, but only after checking it out for myself on my system. I have been brewing for about 18 years now with multiple systems and each and everyone is different in how they react to the brewing process. I love these exbeeriments and hope they cause others to question their methods and see if one of the variables makes sense to change in their system. It is always good to see what affects your system and what doesn’t, but so long as it produces beer that you are proud enough to call your own, it works for you. Always challenge the norm and don’t be afraid to try something new even if it contradicts what you think you know. Beer is a living thing and can only benefit from the changes you make on your own system. Try them out and see what works for you and your brewing style (and your own palate)….Brew on!

“I take the results with a grain of salt. It is a single point in time on a singular system. ”

True, but it is pretty decent science, too. Perhaps “science” that is in the realm of Mythbusters where normal folks are doing the science instead of PhDs but real science nonetheless.

I imagine this website 10 years from now where Xbmt’s have been replicated over and over producing the same result time after time (peer review). Only then can we claim “definitive” methods that produce definitive results.

Cheers!

I’m curious what you do for lager fermentation now. I know you say you treat it as an ale but what are the details?

Thx and as always great work!

When using liquid yeast, I build a start approximately 800 mL to 1 L in size, pitch it into 66°F wort, hold it there for 3-5 days, ramp up to 72°F and let it finish, cold crash, fine with gelatin, then keg and burst carbonate.

I made a “pineapple beer” once–it was an attempt at a Vienna Lager, based on the “Whoop Moffitt” recipe in TCJOHB. Used a dry lager yeast which probably wasn’t 100% viable. I don’t think I rehydrated even. It wasn’t as terrible as it sounds, just was a disappointing effort. I’ve always thought that temperature was the culprit, but after reading Brulosophy I think it’s more likely that it was the combination of factors, and probaly primarily the iffy yeast that caused that. It was ~’93, and dry brewing yeast was probably in general not as high a quality as it is now.

I’ve participated in a few of your xBmts as a taster…. Tonight is our LHBS’s Homebrewer’s Night, where we bring in samples of our beers and taste others’. It always amazes me some of the beers people bring in thinking they are good! Where I’m going with that: Many of the tasters aren’t very sophisticated when it comes to beer. A second issue I’ve noticed is the applicability of science based on 100-barrel batches just doesn’t work the same when applied at five gallons. Take mash temperatures as an example. If I measure the temperature of the mash in my cooler mash tun, I get an inverted “U” shaped graph, lowest at the edges and highest in the middle. So I may well be mashing in the range from 140° to 155° in the same mash. Temperature losses are higher, variability is much higher when I’m measuring 15 grams of hops vs. 500, you see where I’m going. No matter how we try, our experiments just aren’t closely controlled. The most important take-away from Brulosophy so far has been to validate Charlie Papazian’s mantra: Relax, don’t worry, have a homebrew. And that in itself is likely the most significant result of your work so far!

Keep it up! Your studies on pitch rate has saved me buying a 3,000 ml Erlenmeyer for starters….

Great summary after 150 experiments! This might be a great introduction for people who have never explored the website to read first. I, like many homebrewers, had been curious just how important each of the various brewing variables really were to the end product, but felt like I never had the time or money to test these things out for myself. Then I stumbled on your website a year or so again and quickly consumed all of the available content and found myself excited to see what the next experiment would be. I feel like you guys have contributed a great deal to the homebrewing community and the overall knowledgebase of the hobby. You really have become an integral part of the evolution of homebrewing that is happening right now… also I live in Bellingham, WA (well Ferndale actually) and it’s always nice to see a local boy make the big time! Congrats on 150, and I can’t wait to read the next 150!

I worked at group in Ferndale from 2001-2003, it was there that I met the dude who inspired me to start homebrewing. Thanks so much for the encouraging words. Cheers!

This is why I m a patreon. You rock! I m so proud to follow you, you’re an awesome person and an awesome brewer! Thanks for what you have done

You summed it up well; the significance of non-significance. I find value in your approach and what you do which helps formulate my thinking as a brewer. A big thank you from New Zealand and if you ever come down this way – drinks on me!

Marshall,

Irregardless of the critics or the unquestioning ones who see all of the experiments as gospel. I find them very informative and curious most of the time. Your experiment with the hopsack Vs dumping hops in the kettle led me to do an experiment of my own. I will have to admit THEY ARE A LOT OF FUN!! It is pretty exciting going through the process. I just did my first triangle test last night. Should have some results soon to share with the brewing community. Keep doing what your doing and challenging the conventional wisdom in home brewing.. or even pro brewing for that matter. There is so much to explore and learn in homebrewing. You could spend a lifetime doing it and just when you think you have it mastered, some new info comes along and turns it all upside down.

KEEP DOING IT WE’LL KEEP READING!

Brian

Agree about personal preference. Though… I understand why people would want to know on the significant ones. How about not just reporting preferences, but why the taster preferred one over the other?

Collecting, analyzing, and reporting that type of data would be… a mess.

For myself, one of the best things about these 150 xbmts is that it has turned me from a brewer who gets stressed when my mash temp is off by a degree, or a carboy is bumped, to a rhahb kind of brewer, and the hobby has got a lot more fun because I’m not so stressed that my batch will be ruined by small (temperature fluctuations, time differences, etc). So Cheers

False positives aren’t the only statistical hazard. When sample size (number of tasters) is small, significance tests favour the null hypothesis. In other words, a larger proportion of tasters must detect the odd one out if the test is to pass the 95% probability threshold. This is one explanation for the recurrence of nonsignificant results.

However, where the same variable (temp, pitch rate) repeatedly fails to produce an effect, I think you should have the confidence to say you might be onto something – don’t bury your interesting findings in doublethink & cognitive dissonance just because diehards dismiss the results.

Marshall, what you’ve created in Brulosophy is fantastic and you should be proud of your iconoclast status. It’s this attitude that will help push the industry (and homebrewing) forward in innovative ways. People who cherish their practices with religious fervor will continue to make fantastic beer, but I don’t think will be as exciting or leave as much of a mark. It’s a worldview thing, and I applaud your ability to approach variables with scientific intent that isn’t set to confirm, or disprove methods. Bravo!

I love these experiments because they’ve allowed me to cut through the B.S. and superstition and focus on simplifying my routine and making it consistent.

The conclusion should be that if a brewer does everything else perfectly, one mistake does not condemn you to a bad batch.

Wow! Thanks for all these insightful xbeeriments! Certainly has helped me!

I hope lots of new brewers read this. I’ve been brewing since 1993 and have run the gamut from bad liquid extract beers to spending two years trying to make a decent dunkles and focusing on every minute detail (including an article I wrote for Brewing Techniques that never got published) that looked at fermenting in carboys vs buckets on the taste and clarity using a spectrophotometer. Today I buy quality ingredients and mostly just wing it. The beer is always drinkable, though not always perfect, and I spend a lot less energy sweating the small stuff. But interestingly I think most people have to (and should) take that walk through the brewing wilderness to figure out what part of the continuum makes them tick.

Nice work, as always.

Thanks for all the experimentsame guys. I’ve found your results handy from a focus point of view. By that I mean my fermentation stability is ‘about right’ as is my yeast pitch, so rather than pushing either one to the Nth degree, it’s time to explore water chemistry.

One a side note, had you considered publishing these in book format?

How about doing a triangulation experiment between to established beers. Choose 2 that are

similar in a behave similar ABV and colour. We could all remind ourselves of the differences by buying a couple of cans. For example Stella Artois vs Heineken. If the testers could not identify a difference, that would be informative.

After reading your shit for years now, the most important lesson I’ve learned is to relax and have a damn home brew . . . But not until the immersion chill hits the wort.

Yes, nothing matters. But we all know that it DOES matter so try to brew the best beer we can with the knowledge we gain from others. If we screw up? It’s probably not gonna matter. Cheers!

I read the articles for what they are – exbeeriments, so thanks for writing.

I would suggest a special exbeeriment, do all the nothing matters “shortcuts” combined, vs all by the book – head to head.

Why? Well, it seems there is quite a few who think, nothing matters and use these exbeeriments as the holy grale, and there is those who seeks best known good practice.

And to be fair, a lager is not a lager until is has been stored for quite som time 😉