Author: Alex Shanks-Abel

During the mash step, starches present in malted grains are enzymatically converted into sugars that are capable of being metabolized by yeast. While different beer styles have varying levels of sweetness based on the type and amount of grains used, brewers can also manipulate the ultimate sugar content of a beer by adjusting the temperature of the mash. Whereas lower mash temperatures activate the beta amylase enzyme, which results in short-chain sugars that are highly fermentable, higher mash temperatures activate alpha amylase that produce less fermentable long-chain sugars.

It’s widely believed that the presence of these long-chain sugars results in a beer with a perceptible level of sweetness, and hence brewers often select specific mash temperatures based on the style of beer they’re brewing. As a style known for its fermentation character and crisp drinkability, Saison is typically mashed at the lower end of the saccharification range to ensure optimal dryness. According to the conventional wisdom, the residual sugars leftover from higher mash temperatures would lead to levels of sweetness that detract from these other preferred qualities.

On the surface, claims about the relationship between mash temperature and sweetness make sense to me – higher mash temperature leads to a higher FG… higher FG means more sugar… more sugar means more sweetness. However, numerous past xBmts have shown that tasters are generally unable to tell apart beers mashed at vastly different temperatures, despite vastly disparate FG and ABV. With this in mind, I began to wonder what impact mash temperature might have on a beer fermented with a diastaticus yeast strain, which has the unusual ability to break down longer chain dextrins, so I designed an xBmt to test it out!

| PURPOSE |

To evaluate the differences between a Saison mashed cool (148°F/64°C) and one mashed warm (164°F/73°C) then fermented with a diastaticus yeast strain.

| METHODS |

For this xBmt, I went with a simple recipe that I designed for The Brü Club’s AvgBrü series.

Beauty & The Yeast

Recipe Details

| Batch Size | Boil Time | IBU | SRM | Est. OG | Est. FG | ABV |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5.5 gal | 60 min | 21.6 | 6.6 SRM | 1.067 | 1.001 | 8.66 % |

| Actuals | 1.067 | 1.001 | 8.66 % | |||

Fermentables

| Name | Amount | % |

|---|---|---|

| North Star Pils | 6 lbs | 46.15 |

| Rye (Flaked) | 3 lbs | 23.08 |

| Wheat (Flaked) | 3 lbs | 23.08 |

| Turbinado | 1 lbs | 7.69 |

Hops

| Name | Amount | Time | Use | Form | Alpha % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Celeia | 45 g | 60 min | First Wort | Pellet | 3 |

| Styrian Wolf | 15 g | 5 min | Boil | Pellet | 16 |

Yeast

| Name | Lab | Attenuation | Temperature |

|---|---|---|---|

| Napoleon (B64) | Imperial Yeast | 83% | 64.9°F - 75°F |

Notes

| Water Profile: Ca 52 | Mg 0 | Na 0 | CO4 58 | Cl 50 |

Download

| Download this recipe's BeerXML file |

After collecting identical volumes of water in separate kettles, adjusting each to the same mineral profile, and flipping the switches on my controllers to get them heating up, I weighed out and milled the grains.

Once the water for each batch was heated to their respective strike temperatures, I incorporated the grains then checked to ensure each was at my target mash temperatures.

While the mashes were resting, I prepared the kettle hop additions.

Once each 60 minute mash was complete, I removed the grains then boiled the worts for 60 minutes before chilling them and taking refractometer readings showing they were at the same OG.

After transferring identical volumes of wort from each batch to sanitized fermentation kegs, they both received a pouch of Imperial Yeast B64 Napolean.

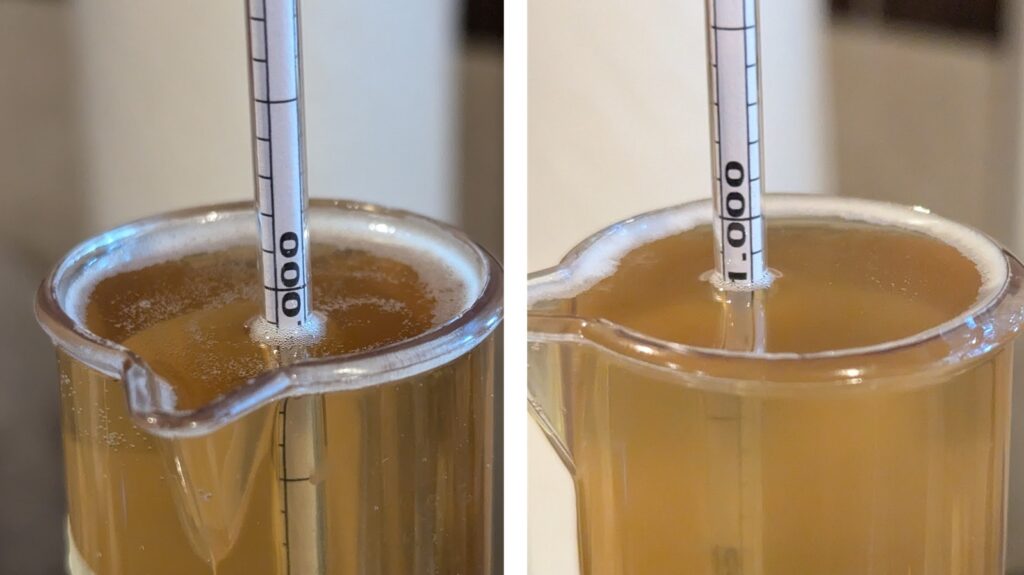

Following 3 weeks of fermentation at 77°F/25°C, I took hydrometer measurements showing a relatively small difference in FG.

At this point, I cold-crashed the beers to 32°F/0°C for a few days then pressure transferred each to CO2 purged serving kegs that were placed in my keezer and left on gas for 3 weeks before they were ready for evaluation.

| RESULTS |

A total of 21 people of varying levels of experience participated in this xBmt. Each participant was served 2 samples of the low mash temperature beer and 1 sample of the high mash temperature beer in different colored opaque cups then asked to identify the unique sample. While 12 tasters (p<0.05) would have had to accurately identify the unique sample in order to reach statistical significance, 14 did (p=0.002), indicating participants in this xBmt were able to reliably distinguish a Saison mashed at 148°F/64°C from one mashed at 164°F/73°C when fermented with a diastaticus yeast strain.

The 14 participants who made the accurate selection on the triangle test were instructed to complete a brief preference survey comparing only the beers that were different. A total of 5 tasters reported preferring the low mash temperature beer, 6 said they liked the high mash temperature more, 2 had no preference despite noticing a difference, and 1 reported perceiving no difference.

My Impressions: Out of the 5 semi-blind triangle tests I attempted, I correctly identified the odd-beer-out just once. These beers were perceptibly identical to me, both possessing the refreshingly crisp, spicy, and citrusy characteristics I expect in a Saison fermented with Imperial Yeast B64 Napolean.

| DISCUSSION |

Mash temperature is used by brewers to adjust the overall fermentability of wort, with lower temperatures leading to dryer beers with lower FGs while higher temperatures result in higher FGs that many believe increases perceptible sweetness. Tasters in this xBmt were able to reliably distinguish a Saison mashed at 148°F/64°C from one mashed at 164°F/73°C when fermented with a diastaticus yeast strain.

Unlike several past xBmts on the same variable, these beers ended up having very similar levels of attenuation with the warm mash temperature beer finishing just 0.001 SG point higher than the low mash temperature batch. While likely a function of the diastaticus yeast, which is known for its ability to ferment long-chain dextrins, the fact tasters could tell the beers apart despite how similar they were seems to suggest something about mash temperature contributed to this difference. To note, the lower mash temperature beer did seem to ferment slightly more vigorously and showed signs of diminished activity sooner than the high mash temperature batch.

Seeing as I was wholly unable to tell these beers apart, I can’t offer much more than speculation as to what was different about them. In post-evaluation conversations tasters, nobody commented on sweetness being a defining factor in these beers, though a number of people alluded to the low mash temperature beer having more bite. Regardless, as someone who prefers lower strength beers, I will continue to lean into warmer mash temperatures for most batches, though I think I’ll start going with lower temperatures when using diastaticus strains, if only to hasten the overall fermentation time.

If you have any thoughts about this xBmt, please do not hesitate to share in the comments section below!

Support Brülosophy In Style!

All designs are available in various colors and sizes on Amazon!

Follow Brülosophy on:

FACEBOOK | TWITTER | INSTAGRAM

If you enjoy this stuff and feel compelled to support Brulosophy.com, please check out the Support page for details on how you can very easily do so. Thanks!

3 thoughts on “exBEERiment | Mash Temperature: Low vs. High In A Saison”

In my anecdotal experience, longer chain sugars taste less sweet than shorter chain sugars, just as complex carbohydrates (starch) taste less sweet than simple carbohydrates (sugar). So when we use a higher mash temperature that results in a higher FG (not relevant here with the monstrous yeast), the beer doesn’t taste sweeter, but might have more body. What seems to result in a sweeter beer is lower mash temperatures combined with a less attenuating yeast that leaves some of those sweeter sugars in the beer. Above all I would say that yeast is the dominant factor in determining how sweet a beer turns out. Again, just anecdotal, but observed over many years of brewing.

Seems like your initial hunch was right – that in fermentation, a diastatic yeast would break down the longer sugars that remained from the high temperature mash. I guess as far as FG is concerned, a diastatic yeast seems like it’s pretty forgiving. As for the flavor difference, my hunch is that the speed of fermentation was the biggest contributing factor because the high temp batch yeast had to wait for fermentable sugars to become available as the enzymes broke down the longer chains.

Great idea for an experiment!

I constantly complain to myself and my wife (she pretends to listen) about the thermometer in my all-in-one electric system. It is off by 3 degrees minimum. I am sure that this will completely destroy my beer when I find out that I am mashing at 149 instead of 152. This article/experiement will help me relax a bit more in the future. Thank you for doing this and all of the other experiements that have made me a better and probably more relaxed brewer.