Author: Jordan Folks

Whereas original versions of IPA tended to balance malt and hops, the last couple decades have seen a shift toward lower malt character with increased hop pungency, one goal being to emphasize the crisp drinkability of this relatively strong style. While this can be accomplished with simplified grain bills, often absent of anything but base malt, many brewers rely on the use of simple sugars that are fully fermentable and thus contribute little perceptible character to beer.

Commonly associated with natural conditioning, dextrose is a monosaccharide made from corn that is highly fermentable and purportedly ferments very clean, making it an optimal choice for brewing applications. Sucrose, or table sugar, is a disaccharide composed of a fructose and glucose molecule that is similarly as fermentable, though many brewers claim it imparts a noticeable cidery flavor to beer.

I’ve been making hoppy West Coast IPA for as long as I’ve been brewing, and I typically use exogenous sugar to drive attenuation while contributing little if anything else to the beer. With two past xBmts suggesting beers made with a portion of dextrose are perceptibly distinct from ones made with sucrose, I decided to test this one out for myself on one my favorite styles.

| PURPOSE |

To evaluate the differences between a West Coast IPA made with a portion of dextrose and one made with the same amount of sucrose.

| METHODS |

For this xBmt, I went with a West Coast IPA recipe that I felt would nicely emphasize the impact of the variable. Big thanks to F.H. Steinbart for hooking me up with the malt for this batch!

Under The Willow

Recipe Details

| Batch Size | Boil Time | IBU | SRM | Est. OG | Est. FG | ABV |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 6.1 gal | 60 min | 68.6 | 4.1 SRM | 1.056 | 1.006 | 6.56 % |

| Actuals | 1.056 | 1.006 | 6.56 % | |||

Fermentables

| Name | Amount | % |

|---|---|---|

| Pilsner | 12 lbs | 75 |

| Wheat Malt | 3 lbs | 18.75 |

| Dextrose OR Sucrose | 1 lbs | 6.25 |

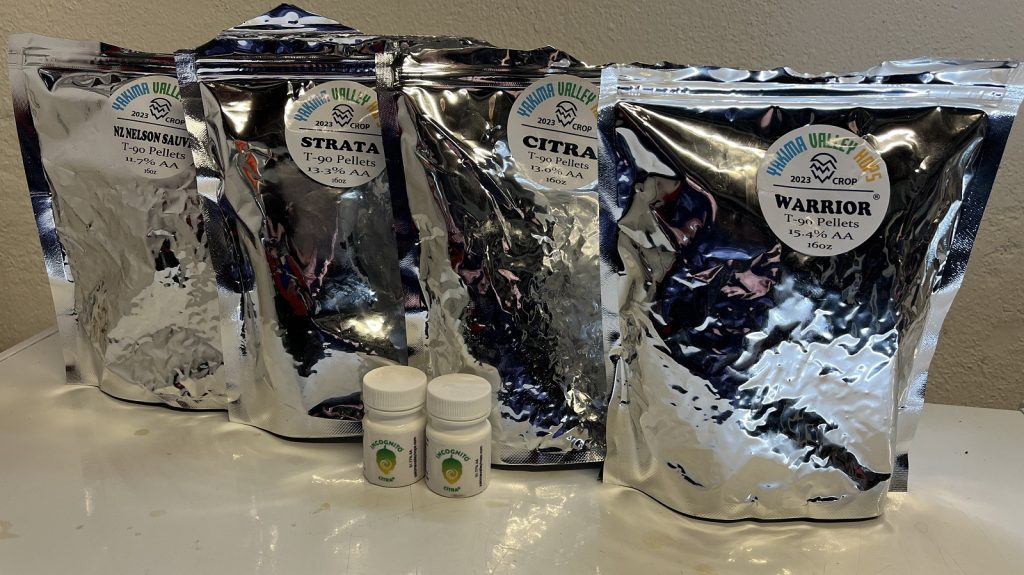

Hops

| Name | Amount | Time | Use | Form | Alpha % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Warrior | 14 g | 60 min | Boil | Pellet | 15 |

| Nelson Sauvin | 14 g | 20 min | Boil | Pellet | 11 |

| Citra | 57 g | 10 min | Aroma | Pellet | 12.5 |

| Nelson | 57 g | 10 min | Aroma | Pellet | 11 |

| Strata | 28 g | 10 min | Aroma | Pellet | 13 |

| Citra INCOGNITO | 20 g | 10 days | Dry Hop | CO2Extract | 12 |

| Nelson Sauvin | 100 g | 2 days | Dry Hop | Pellet | 11 |

| Citra LUPOMAX | 71 g | 2 days | Dry Hop | Pellet | 18 |

| Strata | 28 g | 2 days | Dry Hop | Pellet | 13 |

Miscs

| Name | Amount | Time | Use | Type |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Amylase Enzyme | 1 g | 0 min | Primary | Other |

Yeast

| Name | Lab | Attenuation | Temperature |

|---|---|---|---|

| Global (L13) | Imperial Yeast | 77% | 46°F - 55.9°F |

Notes

| Water Profile: Ca 103 | Mg 4 | Na 10 | SO4 182 | Cl 44 |

Download

| Download this recipe's BeerXML file |

After collecting the full volume of water for two 5 gallon/19 liter batches, adjusting each to my desired profile, and getting them heating up, I milled the grain.

When the waters were properly heated, I incorporated the grain, set each controller to maintain my desired 147°F/64°C mash temperature, then turned the pumps on to recirculate.

During the mash rests, I weighed out the kettle and dip hop additions.

Once the mash was finished, I removed the grains and began heating the worts, at which time I weighed out the different sugars.

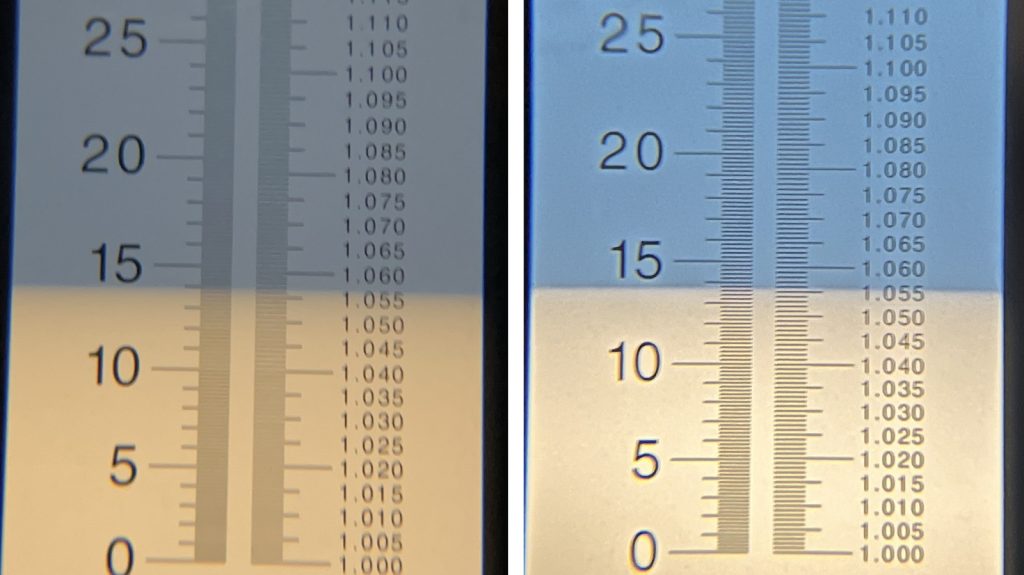

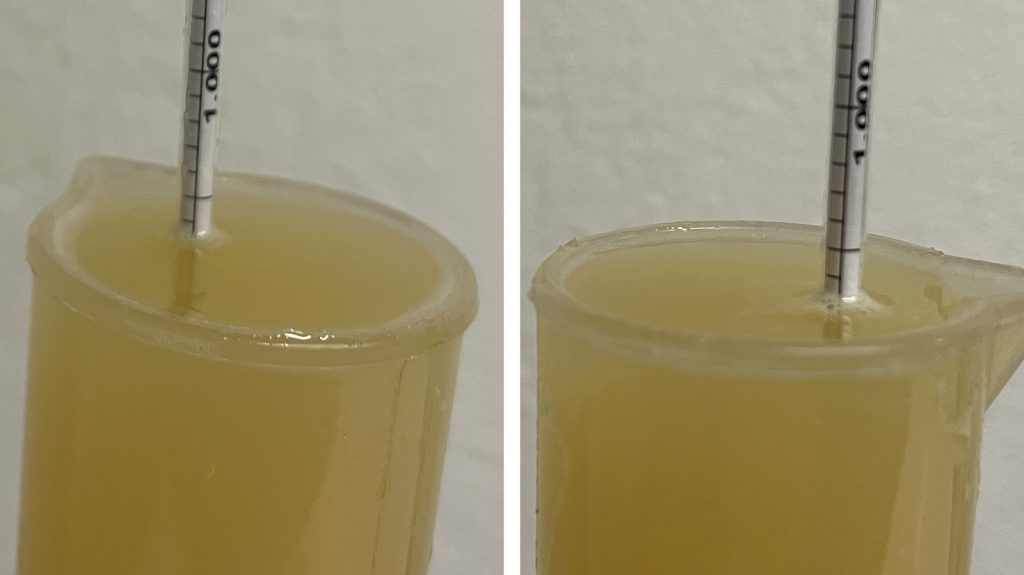

The worts were boiled for 60 minutes with the sugars being added to their respective batches in the final 10 minutes. When the boils were complete, I quickly chilled the worts before taking refractometer readings that indicated both were at the same OG.

Identical volumes of wort from each batch were transferred to separate fermentation kegs before I pitched two packs of Imperial Yeast L13 Global into each.

After 10 days of fermentation at 59°F/15°C, the beers were dry hopped and left alone for 24 hours, at which point hydrometer measurements indicated they were at the same FG.

The beers were then cold-crashed overnight, fined with gelatin, then pressure-transferred to CO2 purged kegs that were placed on gas in my keezer. After a week of cold conditioning, the beers were carbonated and ready for evaluation.

| RESULTS |

A total of 24 people of varying levels of experience participated in this xBmt. Each participant was served 1 sample of the beer made with dextrose and 2 samples of the beer made with sucrose in different colored opaque cups then asked to identify the unique sample. While 13 tasters (p<0.05) would have had to accurately identify the unique sample in order to reach statistical significance, only 5 did (p=0.94), indicating participants in this xBmt were unable to reliably distinguish a West Coast IPA made with a portion of dextrose from one made with the same amount of sucrose.

My Impressions: Out of the 5 semi-blind triangle tests I attempted, I correctly identified the odd-beer-out 3 times. Any differences I thought I noticed between these beers were likely a function of bias, and in the end, both were exactly what I look for in modern West Coast IPA – dry as a bone, immensely hoppy, and extremely drinkable.

| DISCUSSION |

The vast majority of beer styles can be successfully made with malt, though for certain stronger styles like IPA, the use of too much malt can have an undesirable impact on other aspects of the beer, such as body and overall drinkability. One solution involves using simple sugar, the most common being dextrose and sucrose, both of which fully ferment out, though some claim the latter leaves an unpleasant cidery character. Countering this claim, tasters in this xBmt were unable to reliably distinguish a West Coast IPA made with a portion of dextrose from one made with the same amount of sucrose.

One possible explanation for this result is that the amount of sugar used simply wasn’t enough to have a noticeable impact, which even further hidden by this IPA’s hoppiness. Indeed, for the one past xBmt where tasters could tell apart beers made with either dextrose or sucrose, the sugar addition made up 17% of the grist compared to just 6% in this xBmt.

While I’ve tended to rely on dextrose when making hoppy IPA that I wanted to be crisp and crushable, these results as well as my own experience with these beers have definitely led me to rethink my convictions. I’ll likely continue to keep dextrose around in my brewery, though in a pinch, I wouldn’t hesitate to run to kitchen cupboard and use some table sugar, at least for a hopped-up IPA.

If you have any thoughts about this xBmt, please do not hesitate to share in the comments section below!

Support Brülosophy In Style!

All designs are available in various colors and sizes on Amazon!

Follow Brülosophy on:

FACEBOOK | TWITTER | INSTAGRAM

If you enjoy this stuff and feel compelled to support Brulosophy.com, please check out the Support page for details on how you can very easily do so. Thanks!

13 thoughts on “exBEERiment | Sugar Additions: Dextrose vs. Sucrose In A West Coast IPA”

Curious, why the Imperial lager yeast in an IPA. And relatively warm for that yeast at that.

I learned this trick from some reputable California breweries that make some of the best commercial examples of IPAs I know of. This is now my standard practice for all of my WC IPA ferments and I’m absolutely floored by how clean and crisp the resulting beers are.

At the moment a lager yeast is used why not just call it a West Coast IPLAger?

Look at Cold IPA. Uses lager yeast at ~60F, yet still called an “IPA.” IPL was traditionally fermented cold. I would argue the slight ester expression in a warmer 34/70 ferment makes this beer drink more like an ale than a lager. How can a black IPA be called IPA if the P stands for pale? At a certain point, dogmatic adherence to naming conventions can hold back brewing progress and creativity, IMO.

Your point is well taken and I am all for exploration and new creations. Thank you.

The idea that sucrose imparts a cidery flavor stems from the days when 1) yeast quality was still pretty bad, and 2) racking to a secondary carboy was the widely accepted practice. The cider flavor was acetaldehyde due to poor-quality yeast and/or oxygen ingress during racking. It did not come from the sucrose.

Have you got any evidence for that or are you just guessing?

Curious about your water chemistry. I use Brewfather and this doesn’t seem to match any of their profiles. Is this something you’ve tweaked over time?

I tend to write all of my water profiles – I’m not using any of the pre-loaded ones in Brewfather. This is in part because my local water is so low in mineral content, so my original water profiles are built around my starting source profile (which has about 4 ppm Magnesium and 10 ppm sodium). I tend to design water profiles that only require CaCl and gypsum (and acidification agents like lactic acid). I highly recommend this water profile for any dry west coast IPA (the keys are the calcium, chloride, and sulfate levels)

Ok makes sense. I’m in the Pacific Northwest and have source water that is very similar to yours. I’ll add this profile to my app and give it a try. Thanks!

Are you starting with RO water, or is the tap water so low on alkalinity that there is no need to report on it?

I’m using RV-filtered Portland, OR tap water (which has a reported alkalinity of 42 ppm as CaCO3). We don’t report alkalinity or mash pH in our recipes (I always shoot for ~5.4 mash pH via lactic for hoppy beers and sauergut for lagers and Belgians) – so make sure to adjust your water additions based on your source water when relying on our water profiles for a given recipe.

How about a repeat, but including invert sugar?

Sucrose vs. Invert Sugar In A Belgian Tripel, results showed difference was apparent. But that was using around 20% sugar.