Author: Will Lovell

Of the various steps it takes to make a batch of beer, the mash is one of the most important, as it’s where the starches in grain get converted into fermentable sugars. Often times, the mash is performed with a portion of the brewing liquor, the leftover of which is used to sparge, which generally involves rinsing the grain to extract more fermentables after collecting the first runnings.

It’s commonly recommended to sparge with water that’s 170°F/77°C, as cooler water can lead to lower efficiency and warmer water risks extracting unpleasant tannins. While this concept was developed by brewers employing a continuous/fly sparge process, the purported consequences of failing to sparge at the appropriate temperature are apparently not dependent on the specific approach, hence batch sparge brewers also tend to abide by it.

While I rely on full-volume mashing more often these days, back when I was batch sparging, I always made sure to properly heat the sparge water to avoid undesirable off-flavors. Recently, I came across an old xBmt where tasters were unable to reliably tell apart a beer sparged with 170°F/77°C water from one sparged with cool water, which left me wondering what impact sparging with boiling water might have. With a simple Kölsch on deck, I decided to put it to the test to see for myself!

| PURPOSE |

To evaluate the differences between a Kölsch sparged with 170°F/77°C water and one sparged with boiling water.

| METHODS |

Wanting any impact of sparge water temperature to be on full display, I designed a simple Kölsch recipe for this xBmt.

How Many Stanges Has It Been?

Recipe Details

| Batch Size | Boil Time | IBU | SRM | Est. OG | Est. FG | ABV |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5.5 gal | 60 min | 20.1 | 3.7 SRM | 1.053 | 1.009 | 5.78 % |

| Actuals | 1.053 | 1.009 | 5.78 % | |||

Fermentables

| Name | Amount | % |

|---|---|---|

| Llano Pilsner | 10 lbs | 86.96 |

| Denton County Wheat Malt | 1.5 lbs | 13.04 |

Hops

| Name | Amount | Time | Use | Form | Alpha % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mount Hood | 30 g | 60 min | Boil | Pellet | 4.7 |

| Mount Hood | 30 g | 5 min | Boil | Pellet | 4.7 |

Yeast

| Name | Lab | Attenuation | Temperature |

|---|---|---|---|

| Kaiser (G02) | Imperial Yeast | 77% | 55.9°F - 64.9°F |

Notes

| Water Profile: Ca 73 | Mg 0 | Na 0 | SO4 94 | Cl 60 |

Download

| Download this recipe's BeerXML file |

I started my brew day by adding identical volumes of RO water to separate Delta Brewing AIO units, adjusting each to my desired profile, then setting the controller to heat them up before milling the grain. To note – Brewfather indicated a total brewing liquor of around 7.75 gallons/29 liters, so I opted to mash with 3.75 gallons/14 liters and sparge with 4 gallons/15 liters.

Once the water for each batch was adequately heated, I incorporated the grains then checked to make sure both were at the same target mash temperature.

While the mashes were resting, I prepared the kettle hop additions.

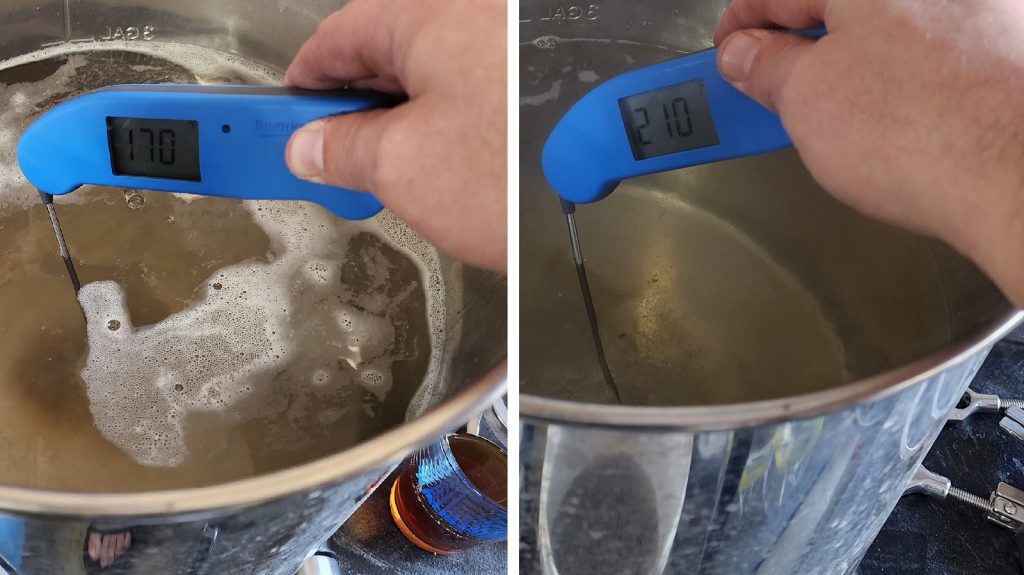

Once each 60 minute mash was complete, I sparged one with 170°F/77°C water while the other was sparged with boiling water.

With identical volumes of wort from each batch collected, they were boiled for 60 minutes with hops added as stated in the recipe.

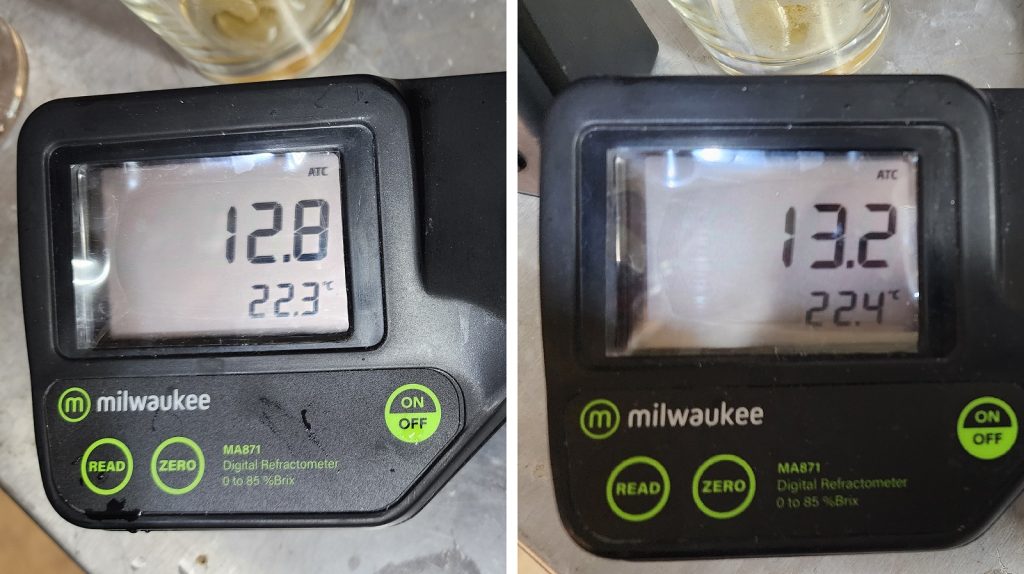

With the boils complete, I quickly chilled the worts with my JaDeD Brewing Hydra IC then took refractometer readings showing a very small difference in OG.

Next, I transferred the same amount of wort from each batch to sanitized Kegmenters.

At this point, I pitched a pouch of Imperial Yeast G02 Kaiser into each before placing them in a chamber controlled to 66°F/19°C.

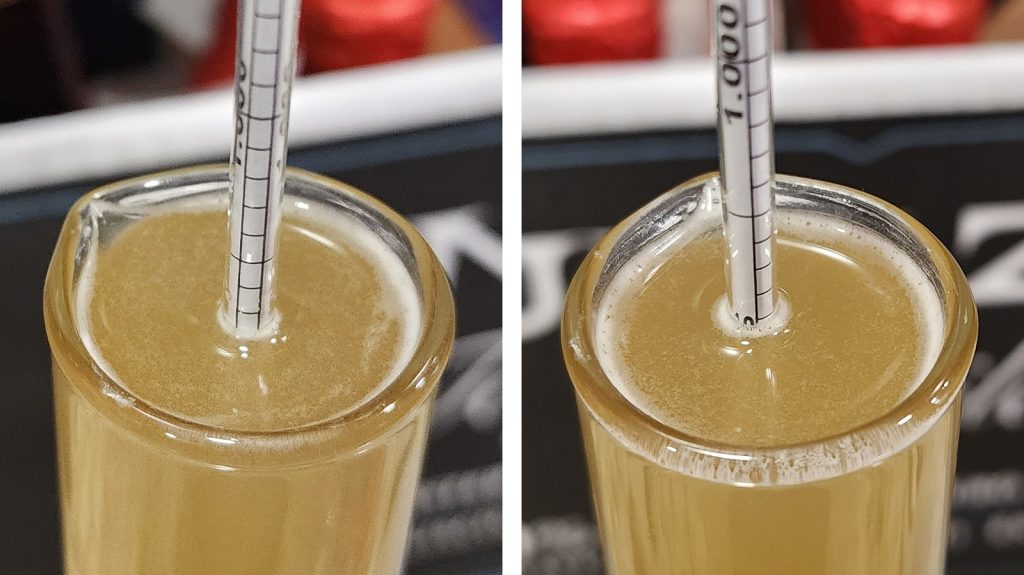

With signs of fermentation absent after a week, I took hydrometer measurements showing the same difference in FG as was observed in OG, indicating similar attenuation.

The beers were pressure transferred to CO2 purged kegs that were placed in my keezer and left on gas for 3 weeks before they were ready for evaluation.

| RESULTS |

A total of 24 people of varying levels of experience participated in this xBmt. Each participant was served 1 sample of the beer made with 170°F/77°C sparge water and 2 samples of the beer made with boiling sparge water in different colored opaque cups then asked to identify the unique sample. While 13 tasters (p<0.05) would have had to accurately identify the unique sample in order to reach statistical significance, 7 did (p=0.74), indicating participants in this xBmt were unable to reliably distinguish a Kölsch made with standard 170°F/77°C sparge water and one made with boiling sparge water.

My Impressions: Out of the 5 semi-blind triangle tests I attempted, I correctly identified the odd-beer-out just twice, indicating my inability to consistently tell them apart. These beers were identical to my in every way, which was a good thing, as both were delicious!

| DISCUSSION |

While seemingly practiced less by homebrewers these days, the sparge step continues to be employed by those looking to achieve high efficiency, particularly on the commercial scale. Ostensibly, the ideal temperature for sparge water is around 170°F/77°C, with lower temperatures leading to lower efficiency while higher temperatures can result in a beer having undesirable astringency. Countering this claim, tasters in this xBmt were unable to reliably distinguish a Kölsch made with standard 170°F/77°C sparge water and one made with boiling sparge water.

It’s possible the beer made with boiling sparge water possessed more tannins than the one made with standard temperature sparge water, but that it wasn’t enough to pass the threshold of perceptibility. That said, tannin extraction has been found to be a function of pH, which was arguably similar between these batches. With that in mind, it can be argued that sparge water temperature may play a bigger role when relying on the fly sparge method, as pH is known to change over the course of the sparge step.

I’ve dabble with both cool and slightly warmer-than-recommended sparge temperatures over the years, but this was the first time I’d ever gone to the extreme of sparging with boiling water, and these results threw me for a bit of a loop. Then again, I’ve had many decocted lagers that possessed no astringency at all, despite the grains actually being boiled, often multiple times, so perhaps sparge water temperature isn’t as important as I’d been led to believe. These days, I usually employ a full volume no-sparge method, but when I do sparge in the future, I’ll certainly not worry as much if the water is off from the recommended temperature.

If you have any thoughts about this xBmt, please do not hesitate to share in the comments section below!

Support Brülosophy In Style!

All designs are available in various colors and sizes on Amazon!

Follow Brülosophy on:

FACEBOOK | TWITTER | INSTAGRAM

If you enjoy this stuff and feel compelled to support Brulosophy.com, please check out the Support page for details on how you can very easily do so. Thanks!

10 thoughts on “exBEERiment | Impact Batch Sparging With Boiling Water Has On A Kölsch”

Tannins extraction is indeed said to happen with high PH and “too hot”water…

When I started brewing, I was very careful with sparging with water around 77 C… Then, I started with boiling water, and never noticed any difference…

And now, I sparge with boiling water and PH around 5.6, and never noticed any difference in taste.

As once a Professional told me… think of decoction. Do they have tannins extractions ?

Decoction is a big reason I wanted to do this xBmt, and I didn’t even bring a portion of the grains to a boil, just the water I was sparging with.

As long as you’re below pH 6, you shouldn’t have much tannin extraction. According to Narziss, a mash pH over 6 is where it gets problematic, even with normal sparging water temperatures of 75-77 °C, and polyphenol extraction (he generalizes it to that, but tannins are a kind of polyphenols) sharply increases.

And that’s also the reason why decoction mashing doesn’t have (much) tannin extraction, because the mash pH remains virtually constant during the boil. Still, a few breweries separate the husks from the endosperm and use a mash filter for lautering to avoid polyphenols in the whole process. But that brings its own problems as the husks are also a source of zinc for the wort. Anyway, that’s all very impractical for homebrewers.

Did you measure the respective temperatures of the mashes during batch sparging? It would be interesting how much of an actual increase in temperature the use of boiling water caused.

It was on my list, but if I did it, I didn’t record it. Unfortunately I recall this being a hectic brew day managing both batches, which is why I don’t have a picture or written record of it.

“…warmer water risks extracting unpleasant tannins”

If there was any truth to this, it would have been noticed many centuries ago–decoction mashing, anyone? Just another homebrew myth.

So this xBmt was done using perception testing. It is entirely possible that if you took these two samples to a lab and measured tannin extraction, they would be different, but I don’t know that for sure. Its probable that one had more tannin, just not at a detectable threshold. All I can say is that in this xBmt under these conditions, tasters could not reliably tell them apart.

Very informative experiment! As my setup suffers with chronic low efficiency, I was especially impressed with the greater extraction of sparging with boiling water. I batch sparge and since pH drop isn’t an issue I will give sparging with boiling water a try.

I’ve always sparged at 180f. I can’t quite remember why though.

Interesting. The big end of town is fixed on 77 to 78 C for sparge water temp. You want to run hot to reduce wort viscosity and reduce lauter time. Running hotter is likely to increase polyphenol extraction but also lipids. You might not notice the impact of this on a fresh beer taste test but lipids reduce flavour stability and polyphenols reduce haze stability. For stable beer stick to 77. For other systems sparge hot