Author: Jordan Folks

In the quixotic quest to perfectly emulate classic European beer styles, many brewers in the U.S. prefer to source their ingredients from the region where the style was developed, believing it has a noticeable impact on the quality of their beer. In no other style is this more prominent than traditional pale lagers– crafting a perfect Czech Pilsner or Munich Helles requires the use of Bohemian or German Pilsner malts, respectively, at least that’s what many believe. However, others prefer using domestic ingredients when brewing such styles, be it for cost savings, sustainability, or imbuing local terroir.

As the second most prominent ingredient used to make beer, water being the first, it makes sense that brewers would focus on the impact it has on their beer, particularly when it comes to delicately flavored styles such as Czech Pale Lager. In addition, growing different varieties, Czech malting approaches historically result in a product with lower modification than their U.S. counterparts, which some traditionalists believe is necessary to achieving the unique organoleptic characteristics Czech lagers are famous for.

I’ve always been a strong believer that producing the most authentic European lagers requires the use of regionally appropriate malts; however, the cost and environmental benefits associated with using domestic malts cannot be denied, which makes this decision a bit trickier. Curious if I’ve been getting perceptible gains from using Czech malts in my Czech lagers, I designed an exBEERiment to test it out.

| PURPOSE |

To evaluate the differences between a Czech Pale Lager made with either Czech or domestic pilsner malt.

| METHODS |

Considering the variable being tested, I designed a simple single malt Czech Pale Lager recipe for this xBmt, one using Great Western Idaho Pilsner and the other using Sladovny Soufflet. Big thanks to F.H. Steinbart for hooking me up with the malt for this batch!

10 Platos To Prague

Recipe Details

| Batch Size | Boil Time | IBU | SRM | Est. OG | Est. FG | ABV |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5.1 gal | 75 min | 25.9 | 2.7 SRM | 1.041 | 1.01 | 4.07 % |

| Actuals | 1.041 | 1.01 | 4.07 % | |||

Fermentables

| Name | Amount | % |

|---|---|---|

| Domestic OR Czech Pils Malt | 8 lbs | 100 |

Hops

| Name | Amount | Time | Use | Form | Alpha % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Saaz | 28 g | 75 min | Boil | Pellet | 2.2 |

| Saaz | 28 g | 30 min | Boil | Pellet | 2.2 |

| Saaz | 57 g | 15 min | Boil | Pellet | 2.2 |

Yeast

| Name | Lab | Attenuation | Temperature |

|---|---|---|---|

| Urkel (L28) | Imperial Yeast | 75% | 57.2°F - 51.8°F |

Notes

| Water Profile: Ca 41 | Mg 4 | Na 10 | SO4 46 | Cl 35 |

Download

| Download this recipe's BeerXML file |

A few days before brewing, I made a single large starter of Imperial Yeast L28 Urkel that would later be split between the batches.

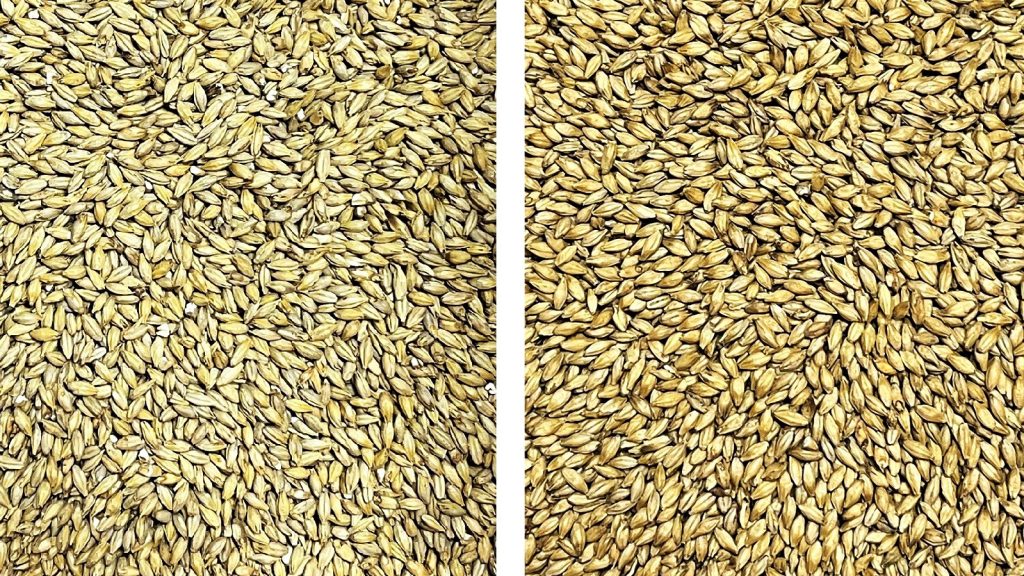

After collecting the full volume of filtered water for each batch, adjusting each to my desired profile, and getting them heating up, I weighed out the grains. Prior to milling, I noticed the domestic malt appeared slightly paler than the Czech malt.

Since this was a classic Czech lager, I opted for a step mash with rests at 144°F/62°C, 160°F/71°C, and 170°F/77°C.

During the mash rests, I weighed out the kettle hop additions.

When the mashes were finished, I collected each wort and proceeded to boil them for 75 minutes, adding hops at the times listed in the recipe.

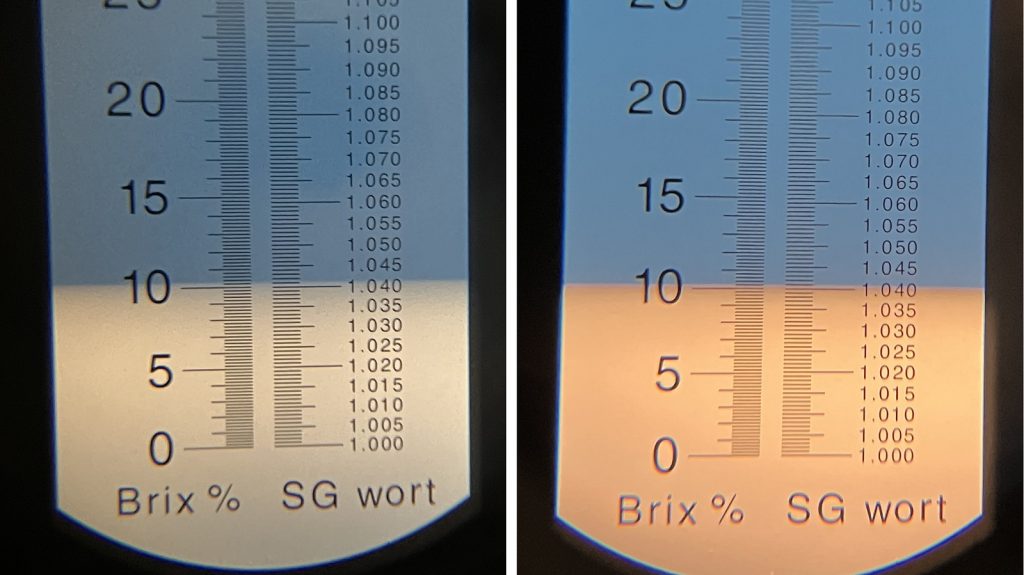

When the boils were complete, I chilled the worts during transfer to sanitized fermenters then took refractometer readings showing both were at the same target OG.

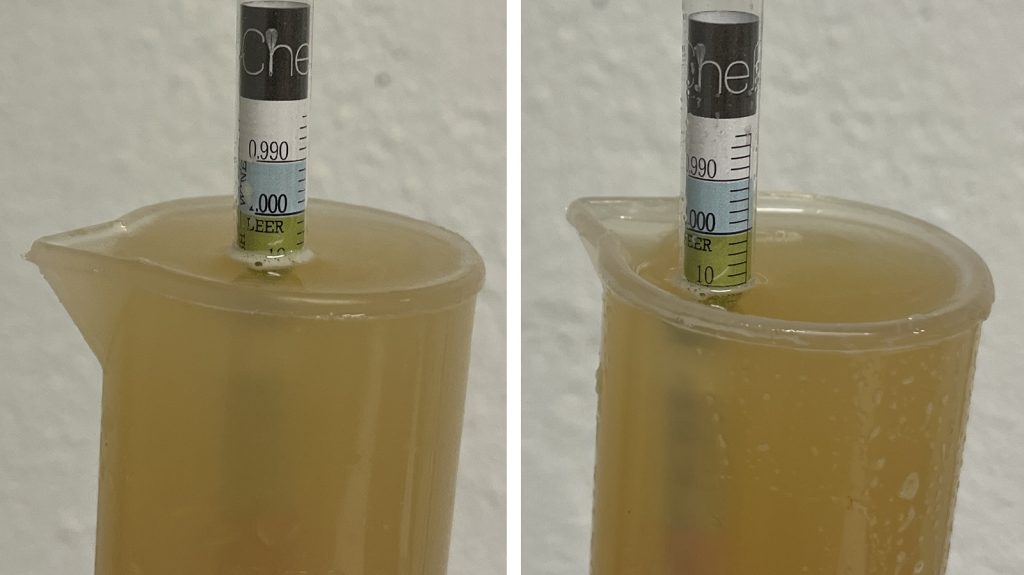

The worts were left to finish chilling to my desired fermentation temperature of 49°F/9°C, at which point I decanted the starter then evenly split the remaining slurry between each batch. After a week of fermentation, I added spunding valves to both fermenters and gradually raised the temperature to 62°F/17°C over the following 2 weeks before taking hydrometer measurements showing a slight difference in FG.

I gradually reduced the temperature of the beers to 32°F/0°C over the course of a few days then pressure-transferred them to CO2 purged serving kegs and fined both with gelatin. The filled kegs were placed on gas in my keezer and left to lager for 1 month before they were ready for evaluation.

| RESULTS |

A total of 27 people of varying levels of experience participated in this xBmt. Each participant was served 2 samples of the beer made with domestic pilsner malt and 1 sample of the beer made with Czech pilsner malt in different colored opaque cups then asked to identify the unique sample. While 14 tasters (p<0.05) would have had to accurately identify the unique sample in order to reach statistical significance, only 11 did (p=0.27), indicating participants in this xBmt were unable to reliably distinguish a Czech Pale Lager made with domestic pilsner malt from one made with Czech pilsner malt.

My Impressions: Out of the 5 semi-blind triangle tests I attempted, I correctly identified the odd-beer-out just once. Although there was a slight visual difference between these beers, the aroma, flavor, and mouthfeel were similar enough to my palate as to make them indistinguishable. I felt both beers were great examples of Czech Pale Lager – light and refreshing with ample flavor.

| DISCUSSION |

When designing any beer recipe, brewers have a wide variety of grains to choose from, and in the case of pale lagers, that typically involves deciding whether to rely on regionally specific pilsner malt or opting for a less expensive domestic product. While many believe the former is necessary for the production of true-to-style European lagers, others feel it doesn’t matter nearly as much as the traditionalists. Interestingly, tasters in this xBmt were unable to reliably distinguish a Czech Pale Lager made with domestic pilsner malt from one made with Czech pilsner malt.

Despite differences in growing region, climate, and likely even barley variety, as well as malting approach, the pilsner malts used in this xBmt were similar enough to produce largely indistinguishable beers. It’s possible this lack of a perceived difference was due to excessive hop and/or yeast character, though considering the style, that seems an unlikely explanation.

As is often the case, prior to my own triangle test attempts, I felt I detected a slight my noticeable difference between the beers in side-by-side samplings, an what I perceived unsurprisingly aligned with common conceptions of these malts. Lo and behold, when blind to which beer was in which cup, those differences faded such I couldn’t consistently tell them apart. While I’ve historically tended to gravitate toward continental pilsner malts when making classic European pale lagers, I’ve been emboldened by these results to use domestic alternatives when regionally appropriate options aren’t handy.

If you have any thoughts about this xBmt, please do not hesitate to share in the comments section below!

Support Brülosophy In Style!

All designs are available in various colors and sizes on Amazon!

Follow Brülosophy on:

FACEBOOK | TWITTER | INSTAGRAM

If you enjoy this stuff and feel compelled to support Brulosophy.com, please check out the Support page for details on how you can very easily do so. Thanks!

6 thoughts on “exBEERiment | Grain Comparison: Domestic vs. Czech Pilsner Malt In A Czech Pale Lager”

Very interesting experiment! I appreciate that you brewed a straight 10 Plato svetle pivo with no shenanigans.

I’ve been trying unsuccessfully to source any Czech malt – it’s surprisingly difficult considering I live not too far away, in Bavaria.

I’m also not convinced the grain itself is radically different from the stuff that grows over here, but malting techniques might differ.

Also, in before people say that you’re wasting the Czech malt when not doing a decoction, that both batches were oxidized, which destroyed the subtle malt flavours, or that you ought to have brewed a stronger beer to make the malt shine more.

I’m planning to brew a Pilsner soon and may model it off your recipe (I recently brewed one of your IPL recipes and it turned out great).

I’m curious about the 75 minute boil. I’ve been doing 30 minute boils for awhile now to cut down on brew time and haven’t noticed any major issues with the end resulting beer. Is there a reason this style gets a 75 minute boil versus a 60 or 30 minute boil? Thanks!

I design my recipes around a 60-minute boil, and sometimes extend the boil time if the mash efficiency was lower than predicted in my Brewfather recipe. This is one of those cases. 60-minute boil time is sufficient for this. I’m sure a 30-minute boil would make a great beer too – but obviously account for your grain/hop amounts accordingly.

Ok great. Thank you!

Actually I do have one more question. When making Pilsner have you found a noticeable difference between Imperial Global and Urkel yeasts? Looking through Brulosophy recipes it seems like they are used pretty interchangeably for this style. I normally have access to both and am leaning towards Urkel since it’s specific to the Czech Pilsner style, but just curious if Global gives basically the same results in your experience.

This is something I’ve been meaning conduct an xbmt on actually! I swore Urkel had a “Czech” flavor, but I was shocked at how authentically Czech the beers tasted at Toronto’s Godspeed once their brewer told me they use 34/70 (Global). Urkel can throw more diacetyl than Global – so if you’re not good at mitigating diacetyl, then Urkel could very well taste different. As long as you have access, might as well use Urkel for Czech lagers and Global for German. At a certain point, it’s not really a Czech lager in my opinion if you don’t use any Czech ingredients – so try to source Czech malt, hops, and/or yeast if you can (if Czech Pilsner is your goal).