Author: Mike Neville

Arguably, the key to creating the best IPA is figuring out how to pack in as much hop character, which is certainly the case when it comes to Hazy IPA. While flameout (or whirlpool) additions have been commonplace for quite some time, some modern brewers have been relying on the hop stand method, which involves adding hops to wort that has been chilled to a certain temperature and letting it sit for a set amount of time.

Hop stand advocates purport that by reducing wort temperature before adding hops, then allowing the hops a 15 to 20 minute mingling period, not only will there be less isomerization, but fewer desirable terpenes will volatilize, resulting in a beer with more pungent hop character. However, those who question this claim often point to evidence that most hop terpenes have volatilization points that are higher than wort boiling temperature, such as myrcene, the most abundant terpene in hops, which has a boiling point of 330°F/166°C.

Many of my recipes have a hop stand addition, and while I’ve felt it’s had positive impact, results from a number of prior xBmts have failed to support this method as being any more efficacious than kettle hopping. Still, given my presumed success with hop stands, I remained curious and designed an xBmt to test it out for myself on a Hazy IPA.

| PURPOSE |

To evaluate the differences between a Hazy IPA that received a 20 minutes hop stand at 203°F/95°C and one that received the same addition at 185°F/85°C.

| METHODS |

For this xBmt, I went with a Hazy IPA recipe that was inspired by past batches I was pleased with.

Splitting The Difference

Recipe Details

| Batch Size | Boil Time | IBU | SRM | Est. OG | Est. FG | ABV |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5.5 gal | 30 min | 121.1 | 4.6 SRM | 1.065 | 1.01 | 7.22 % |

| Actuals | 1.065 | 1.01 | 7.22 % | |||

Fermentables

| Name | Amount | % |

|---|---|---|

| Pelton: Pilsner-style Barley Malt | 9 lbs | 61.02 |

| Lamonta: Pale American Barley Malt | 2 lbs | 13.56 |

| Wheat | 2 lbs | 13.56 |

| Oats, Flaked | 1.5 lbs | 10.17 |

| Rimrock: Vienna-style Rye Malt | 4 oz | 1.69 |

Hops

| Name | Amount | Time | Use | Form | Alpha % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Idaho #7 | 142 g | 20 min | Aroma | Pellet | 12.5 |

| Mosaic | 85 g | 20 min | Aroma | Pellet | 11.2 |

Yeast

| Name | Lab | Attenuation | Temperature |

|---|---|---|---|

| Capri (I22) | Imperial Yeast | 75% | 32°F - 32°F |

Notes

| Water Profile: Ca 130 | Mg 26 | Na 5 | SO4 99 | Cl 191 |

Download

| Download this recipe's BeerXML file |

After collecting identical volumes of water for each batch, I weighed out and milled the grain.

With the water properly heated, I incorporated the grains then checked to make sure the mash was at my target temperature.

During the mash rest, I prepared the kettle hop additions.

Once the 60 minute mash was finished, I sparged to collect my target pre-boil volume then proceeded to boil the wort for 30 minutes, reserving all hop additions for the hop stand.

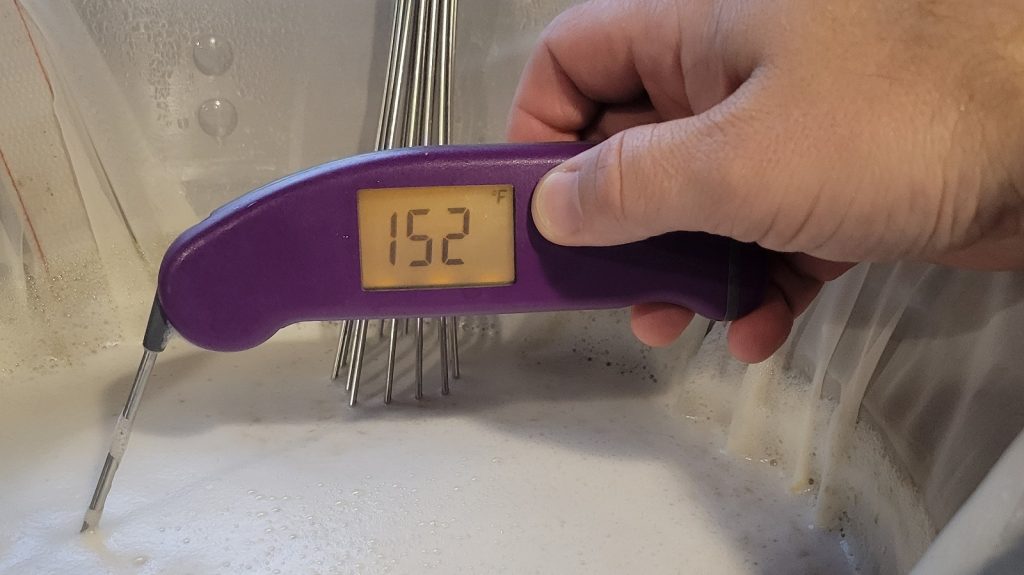

When the boil was complete, I quickly chilled the worts to 203°F/95°C and 185°F/85°C then added identical amounts of hops. Following a 20 minute hop stand, I finished chilling the worts with my JaDeD Brewing Hydra IC.

Next, I transferred identical volumes of wort to separate fermenters.

Refractometer readings showed the warm hop stand wort had a slightly higher OG than the cool hop stand wort.

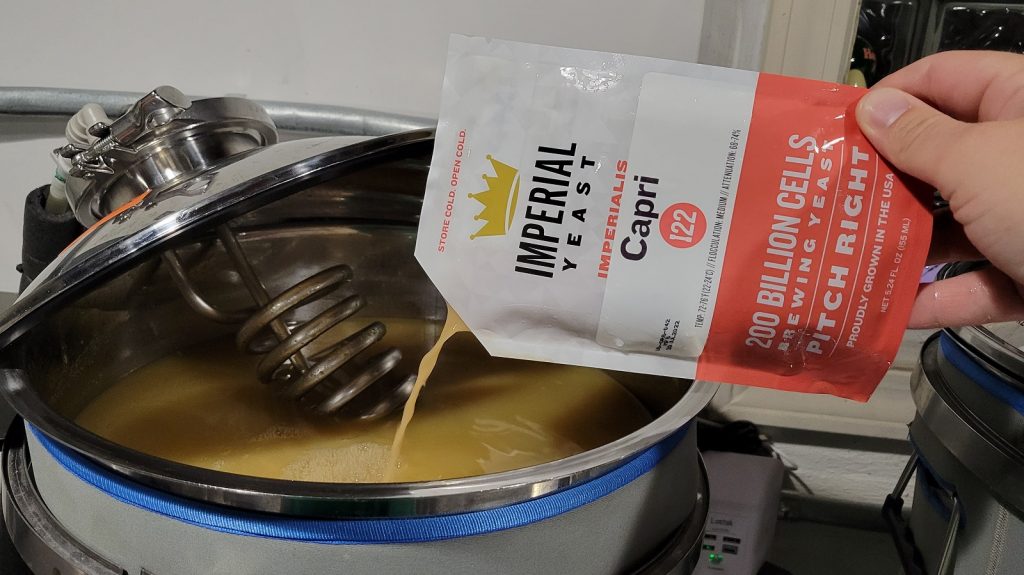

The fermenters were connected to my glycol unit and allowed to finish chilling to my desired fermentation temperature of 74°F/23°C, at which point I pitched a single pouch of Imperial Yeast I22 Capri into each batch.

In order to isolate the variable as much as possible, I skipped dry hopping this beer and, after a week of fermentation, took hydrometer measurements that showed a minor difference in FG.

At this point, I cold crashed both beers to 38°F/3°C and let them sit overnight before pressure transferring them to CO2 purged kegs.

The filled kegs were placed in my keezer and burst carbonated overnight before I reduced the gas to serving pressure. After a week of conditioning, they were carbonated and ready for evaluation.

| RESULTS |

A total of 22 people of varying levels of experience participated in this xBmt. Each participant was served 2 samples of the warm hop stand beer and 1 sample of the cool hop stand beer in different colored opaque cups then asked to identify the unique sample. While 12 tasters (p<0.05) would have had to accurately identify the unique sample in order to reach statistical significance, only 8 did (p=0.46), indicating participants in this xBmt were unable to reliably distinguish a Hazy IPA that received a 20 minute hop stand at 203°F/95°C from one that received the same addition at 185°F/85°C.

My Impressions: Out of the 5 semi-blind triangle tests I attempted, I correctly identified the odd-beer-out 3 times, which isn’t consistent enough to indicate any differences I thought I perceived actually existed. In side-by-side comparisons, I felt like the warm hop stand beer may have been slightly more bitter than the cool hop stand version, but not by much, and they were otherwise identical, both possessing a dank ripe pineapple flavor with low levels of blueberry and a pillowy mouthfeel.

| DISCUSSION |

It seems brewers of modern versions of IPA are constantly seeking ways to increase hop character in their beer without imparting undesirable characteristics such as vegetal off-flavors, which are associated with over dry hopping. One such method is the hop stand, which involves steeping hops in wort post-boil, with some preferring to chill the wort a bit in order to avoid volatilizing desired terpenes. The fact tasters in this xBmt were unable to reliably distinguish a Hazy IPA that received a 20 minute hop stand at 203°F/95°C from one that received the same addition at 185°F/85°C suggests any differences were minimal enough as to be grossly imperceptible.

In the entire history of brewing, the hop stand method is a relatively new development that was driven by the collective craze for IPA. Somewhere along the line, it seems brewers accepted the idea that hop terpenes like myrcene have low volatilization points, despite evidence indicating it’s actually much higher than wort boiling temperature. It seems likely this explains the non-significant results of this and many past hop stand xBmts.

Performing a hop stand on my system is quite easy, and while these results suggest temperature may not play as big of a role as many believe, I’ll still use the method when making certain styles of beer. To keep things simple, I’ll likely stick with flameout additions, though when I’m looking to reduce my brew day length, I won’t fret about making late boil additions.

If you have any thoughts about this xBmt, please do not hesitate to share in the comments section below!

Support Brülosophy In Style!

All designs are available in various colors and sizes on Amazon!

Follow Brülosophy on:

FACEBOOK | TWITTER | INSTAGRAM

If you enjoy this stuff and feel compelled to support Brulosophy.com, please check out the Support page for details on how you can very easily do so. Thanks!

7 thoughts on “exBEERiment | Impact Hop Stand Temperature Has On A Hazy IPA”

Why were such similar temperatures chosen for the hop stand? My typical temperature is in the 165-175F range to prevent DMS accumulation, and prevent isomerization.

I would agree with Cory that a more noticeable difference the lower temperature half would be achieved in the 150-160°F range, which is where I prefer to go for hopstand/whirlpool additions… Also I think that the ~50° lower temp benefits from a longer exposure time of 30-60min though that may just be anecdotal…

Why would the OG be different? Interesting

Great experiment! At the risk of repeating some of the other commenters, the temperatures chosen seem a little weird. Both 185 F and 203 F would generally be considered a “hot” hopstand. Heck, 203 F is higher than the boiling point in Denver! My brewing software, for instance, defaults to 175 F for hop stands, and as some others mentioned, 150-165 F is common as well.

As an aside, if the variable you were testing was a post-boil variable, wouldn’t you have been able to further isolate to the variable by brewing one batch and splitting it? I know there was no significant difference perceived at this sample size, but still it seems weird that you would brew two objectively different batches and then still run the test as if they were the same when you could have made them literally the same by splitting a single batch. Not trying to be critical! Just trying to discuss what’s presented.

Cheers!

Janish summarized some hop stand/whirlpool temp studies in the New IPA book and they showed a difference at even closer temps, 185 vs 195F IIRC. Plus, I think 185F is pretty standard for hop stand temp, so comparing that to post boil temp (203F) makes a lot of sense to me for the first experiment. A future version should stretch the temp difference but still needs to be brewing relevant.

On this chart of terpene vaporization all terpenes listed vaporize at temperatures above boiling.

Scroll down about one page to the chart

https://catalyst.honahlee.com.au/article/terpene-chart-vaporisation-temperatures/

This is a pretty short duration for a hop stand. I think the original research by Ray Daniels going a ways back found that 80 minutes provided the optimum benefit. In my experience, I think 30-45 minutes is the minimum to see a notable difference between a hopstand and just a flameout addition.

Hop stands started as a way to approximate the results that commercial breweries get from whirlpool additions, which are quite a bit longer due to the nature of their systems. It wouldn’t surprise me if you saw a more notable difference at double the length of your hop stand. This also leads to another possible xBmt – comparing hop stand lengths, or comparing a hop stand addition to a flameout addition.