Author: Paul Amico

These days, there are numerous types of IPA that have their own unique qualities, though one thing they all share is a strong hop character. One of the most popular methods for imparting beer with heaps of hop aroma is dry hopping, which involves adding a dose of hops to the beer during fermentation. However, with the rise in popularity of IPA, brewers began to experiment with new ways to maximize hoppiness in their beer.

While adding hops to the boiling wort will certainly result in some aroma and flavor, the temperature is known to quickly volatilize the precious hop oils, sending them into the atmosphere rather than keeping them in the beer. For this reason, some brewers opt to make hop additions to the wort once it has been chilled a certain extent, though before the yeast is pitched. At a temperature around 170°F/77°C, most hop oils are less susceptible to volatilization, so an extended steep of around 15 minutes is believed to allow ample time for those oils to get into the wort.

It’s been my experience that brewers aren’t necessarily choosing one method over the other, but usually do both a hop stand and dry hop addition when making IPA. However, I’ve heard from some that believe using both is overkill, as they contribute similar levels of hop character. With a past xBmt showing tasters could reliably distinguish an American Pale Ale that received a 20 minute hop stand at 165°F/74°C from one dry hopped with the same amount of hops, I was curious how things would play out in a stronger, more assertively hopped IPA and designed an xBmt to test it out!

| PURPOSE |

To evaluate the differences between an IPA made with a 20 minute hop stand at 170°F/77°C and one that is dry hopped with the same amount of hops.

| METHODS |

For this xBmt, I went with a fairly simple American IPA recipe using a couple of my favorite LUPOMAX hops.

New Old Friends

Recipe Details

| Batch Size | Boil Time | IBU | SRM | Est. OG | Est. FG | ABV |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5.5 gal | 60 min | 45.7 | 7.5 SRM | 1.065 | 1.018 | 6.17 % |

| Actuals | 1.065 | 1.018 | 6.17 % | |||

Fermentables

| Name | Amount | % |

|---|---|---|

| Lamonta: Pale American Barley Malt | 10 lbs | 64.52 |

| Pelton: Pilsner-style Barley Malt | 5 lbs | 32.26 |

| Caramel Malt 40L | 8 oz | 3.23 |

Hops

| Name | Amount | Time | Use | Form | Alpha % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cascade LUPOMAX | 9 g | 60 min | First Wort | Pellet | 12.5 |

| Mosaic LUPOMAX | 6 g | 60 min | First Wort | Pellet | 17.5 |

| Cascade LUPOMAX | 11 g | 15 min | Boil | Pellet | 12.5 |

| Mosaic LUPOMAX | 8 g | 15 min | Boil | Pellet | 17.5 |

| Cascade LUPOMAX | 16 g | 5 min | Boil | Pellet | 12.5 |

| Mosaic LUPOMAX | 12 g | 5 min | Boil | Pellet | 17.5 |

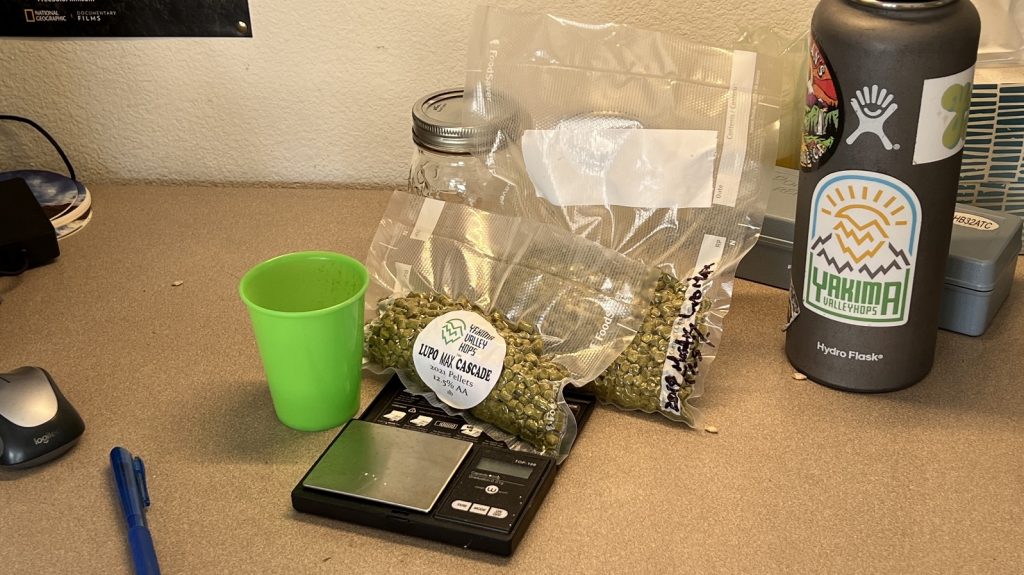

| Cascade LUPOMAX (OR HOP STAND) | 28 g | 4 days | Dry Hop | Pellet | 12.5 |

| Mosaic LUPOMAX (OR HOP STAND) | 28 g | 4 days | Dry Hop | Pellet | 17.5 |

Yeast

| Name | Lab | Attenuation | Temperature |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pub (A09) | Imperial Yeast | 74% | 32°F - 32°F |

Notes

| Water Profile: Ca 92 | Mg 1 | Na 10 | SO4 153 | Cl 50 |

Download

| Download this recipe's BeerXML file |

I started this brew day by collecting the water for a single 10 gallon batch, which I adjusted it to my desired profile.

After flipping the switch on my Clawhammer Supply 240v controller to get the water heating up, I weighed out and milled the grain.

With the water properly heated, I incorporated the grains then checked to make sure the mash was at my target temperature.

During the mash rest, I prepared the kettle hop additions.

When the mash rest was complete, I removed the grains and began heating the sweet wort.

When the boil was complete, I chilled half with my CFC during transfer to a sanitized fermenter.

I then proceeded to recirculate the remaining wort through the chiller until it reached 170°F/77°C, which I set my controller to maintain before adding the hop stand addition. After 20 minutes, I transferred an identical amount through my CFC to another sanitized fermenter, then placed both in my chamber to finish chilling overnight before pitching a single pouch of Imperial Yeast A09 Pub into each.

After 3 days of fermenting at 66°F/19°C, I returned to add the dry hop addition, making sure to remove the lid from the hop stand batch for a similar amount of time.

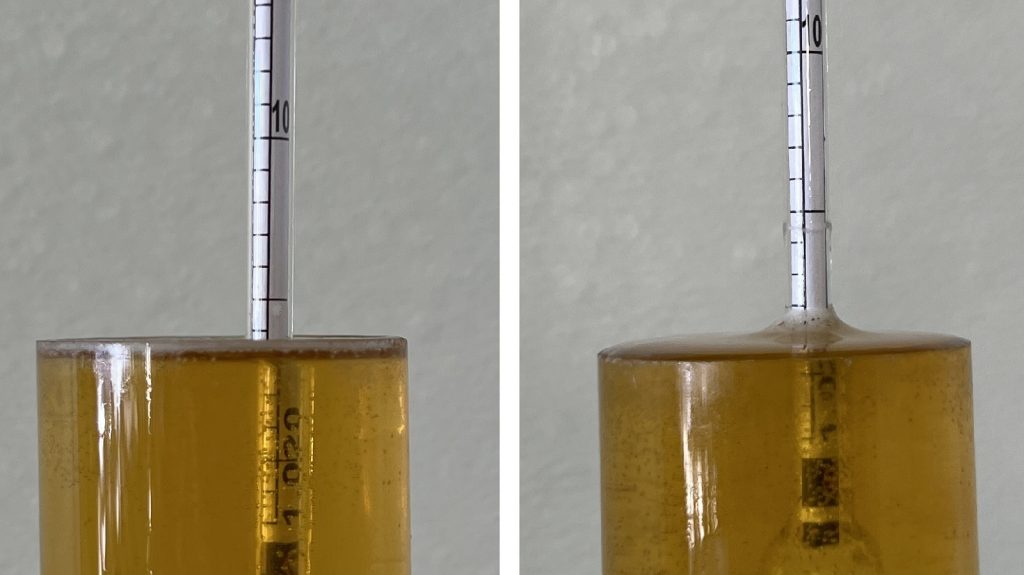

The beers were left alone for another 4 days before I took hydrometer measurements showing a minor difference in FG.

At this point, I proceeded with transferring the beers to CO2 purged kegs.

The filled kegs were placed in my keezer and burst carbonated overnight before I reduced the gas to serving pressure. After a week of conditioning, they were carbonated and ready for evaluation.

| RESULTS |

A total of 26 people of varying levels of experience participated in this xBmt. Each participant was served 2 samples of the hop stand beer and 1 sample of the dry hop beer in different colored opaque cups then asked to identify the unique sample. In order to reach statistical significance, 14 tasters (p<0.05) would have had to accurately identify the unique sample, which is exactly how many did (p=0.025), indicating participants in this xBmt were able to reliably distinguish an American IPA made with a 20 minute hop stand at 170°F/77°C from one dry hopped with the same amount of hops.

The 14 participants who made the accurate selection on the triangle test were instructed to complete a brief preference survey comparing only the beers that were different. A total of 4 tasters reported preferring the hop stand beer, 9 said they liked the dry hop beer more, and 1 reported perceiving no difference.

My Impressions: Out of the 5 semi-blind triangle tests I attempted, I correctly identified the odd-beer-out just 2 times, which isn’t consistent enough to indicate I could easily tell these apart. I perceived both beers as having similar levels of hop character, though if forced to choose, and despite my triangle test performance, I would say I preferred the dry hopped version.

| DISCUSSION |

The one thing every type of IPA is expected to possess is strong hop aroma and flavor, which brewers impart through the use of various techniques including hop stands and dry hopping. Countering claims that these methods result in similar levels of hop character, tasters in this xBmt were able to reliably distinguish an American IPA made with a 20 minute hop stand at 170°F/77°C from one dry hopped with the same amount of hops.

Considering the fact both batches in the xBmt were dosed with the same amount of hops, it seems possible volatilization of hop oils during the warm hop stand or maybe even biotransformation explains these results. Then again, the hops from the dry hop batch were in contact with the beer up until kegging, which may have led to a more intense hop character.

I’ve brewed a lot of IPA over the years and have always appreciated what dry hopping does for them, though I’ve also done numerous hop stands and always felt it contributed more hop character. Based on these results, I’m compelled to believe dry hopping may impart beer with more pungent hop aroma, though I’ll certainly continue using both methods together when making IPA in the future.

If you have any thoughts about this xBmt, please do not hesitate to share in the comments section below!

Support Brülosophy In Style!

All designs are available in various colors and sizes on Amazon!

Follow Brülosophy on:

FACEBOOK | TWITTER | INSTAGRAM

If you enjoy this stuff and feel compelled to support Brulosophy.com, please check out the Support page for details on how you can very easily do so. Thanks!

40 thoughts on “exBEERiment | Hop Stand vs. Dry Hop In An American IPA”

How long did runoff take to the first fermenter? Seems as though the hop stand batch would have spent a little longer at pre chill temperature and I wonder if that could have added another variable?

I still think testers should be served 2 samples of EACH beer. I believe this would increase accuracy and eliminate SOME of the guessing. Anyone know why they don’t do it that way? Would it show how much guessing there actually is?

That’s not how triangle tests work…

Duh ! So why not use a more reliable test. A lot harder to guess 2 out of 4 instead of 1 out of 3.

To expand on that, triangle tests are a very common method for performing taste tests on beer, which provides the advantage of creating a common foundation for comparing tests performed by different places.

In addition, tests performed by a single organization over time using the same method allow results over time to be compared with a higher degree of confidence than using different methods.

There are reasonable alternatives, such as the duo-trio and tetrad tests, which are summarized in this report published by the NIH. It’s important to note that there is no perfect method — changing methods has benefits and drawbacks no matter what.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC8834440/

The bottom line, though, is that triangle tests were a solid choice by Brulosophy. They’re easy to administer (and avoid mistakes), they produce results which are pretty easy to crunch, and they’re a well respected method.

I think it’s important to note that these tests are only limited data points. If this was Miller testing out a new citrus lite malt seltzer, they would perform huge numbers of tests on every single possible variable and all kinds of different test groups. The cost of product testing for a large brewer can far exceed seven figures. That’s obviously not going to happen here. But it’s still interesting to see the results.

Triangle tests are a tool to more easily get to statistical significance, especially with smaller sample sizes. If you had an equal number of each sample then it’s a 50/50 guess to get it right. It makes it more difficult to get to statistical significance compared to a 1/3 chance of getting the odd beer out correct in a Triangle test.

Not if it is all guessing.

@Richard everybody here is being more than patient, but you simply don’t understand the mathematics behind the statistical significance of the triangle tests, nor what that all means, so you should really just leave it at that.

cheers,

Glad you are a mathematician. Maybe you could explain Schrodinger Equation to me. I always had a hard time with the back coupling of the wave function.

@richard actually, I can explain pretty much anything about the Schrödinger equation, having gotten my degree(s) in nuclear physics (and differential geometry). What would you like to know about it?

Now who is the troll.

@richard merely stating a fact! 😎✌️

now I know what an internet Troll 👹 is…

Wouldn’t the chance of guessing correctly be 1 in 3

dear Brüs !

That would bee really fantastic to add DATE to your articles !!!

thanx a lót

What’s at work that the dry hopped one has a higher final gravity? I would expect slightly lower if anything.

Years ago I tried replacing all my dry hopping with various hop stand time/temperature/quantity combinations. No matter what I tried, I found that something was lacking and I have since gone back to dry hopping (often in combination with hop stands). I find that I get more aromatic punch, and a different flavor contribution from dry hopping than hop stands.

Paul, nice additional to the knowledge base of the home brewer.

Team: This might be a great time to pull together “the show so far”: summarize all of the Brulosophy experimental results for hop additions in one article. In other words, what do we know so far? What really makes a perceptible difference? Such a summary could also be used to guide the next experiments to advance the knowledge base and fill in gaps. For example, I think you’re getting closer to defining an evidence-based, best-practice hop aroma and flavor addition schedule for pale ale and IPA.

I love Brulosophy, putting long-accepted conventional wisdom/claims/opinions to the test.

I think you would find a lot of conflicting articles if they were all lumped together by category. But fun to read.

Interestingly, I posted the results of myesimilar exBeeriment in David Heath’s FB group on the same day (yesterday) at about the same time you posted this. here’s what I wrote:

ExBeeriment : Hop Stand vs. (D)Dry Hop vs. Hop Tea

After lengthy discussion of the efficacy of Hop Stands compared to Dry Hopping and Hop Teas (search here for a few threads from a couple months ago) I performed the following exBeeriment, the results of which I summarize below.

A single batch of Verdant‘s „Even Sharks Need Water“ was brewed according to their publically released recipe. Here‘s the batch recipe I brewed:

Batch #18 – Even Sharks Need Water – Verdant https://share.brewfather.app/NL1BYj3eWqSQRY

After flame out and cooling to Hopstand temperature, two-thirds of the wort was first transferred thru my CFC to two separate FVs (one-third of the batch in each). In the remaining one-third a hop stand (using one third of the hop stand hops shown in the recipe) was performed and then transferred thru my CFC to a third FV, and all three received the same amount (1/3 Package) of Verdant IPA yeast.

Near the end of primary fermentation, while still several points away from FG, all three received a dry-hop according to recipe, one receiving an additional amount of dry hops using the same amount of hops that were used in the hop stand.

On packaging day, the remaining batch received a Hop Tea made with the same amount of hops as were used in the hop stand.

After bottle conditioning, the three different batches were labeled A, B, C, and presented to several panels of varying skill and experience, from novices to amateur beer judges, for blind taste-testing. There were a total of 10 “judges”.

Interestingly, the results were unanimous, every group rating the beers in the same order: Hop Stand as best, extra dry hop second and Hop Tea third place. I personally also thought the Hop Stand beer was best, having more depth in hop flavor and fruitiness, the dry hopped beer being a close second. The Hop Tea beer was found to be flatter and more one-dimensional.

I had actually expected and thought to demonstrate that a hop stand might be the least effective way of getting hop flavor and aroma into the final beer, the logic being that a lot of aroma is released to the atmosphere and/or is bubbled off during fermentation and escapes with the CO2. I had expected to demonstrate that Hop Tea was the most effective, the logic being that the aroma and flavor goes into the beer immediately before packaging and hence is preserved the best. Since I demonstrated to myself the exact opposite of my expectations, I found this to be very convincing.

please note that the “hopstand beer” in my exBeeriment also had a dry-hop! the exbeeriment is actually: hopstand+dry hop vs. double dry hop vs. hop tea+ dry hop.

Just goes to show how Unreliable all these tests are.

@richard how do you figure? Brulosophy tested hopstand only vs. dry hop only and dry hop (marginally) won. I tested hopstand+dryhop vs. double-sized dry-hop and hopstand+dry hop clearly won. I see no contridiction in the fact that the combo hopstand+dry hop might be the winning combo, the whole being greater than the sum of it’s parts. now we need a hopstand only vs. dry hop only vs hopstand+dry hop to clinch it.

Richard, please explain.

What an unreliable comment.

My point is that triangle tests are not reliable. The chance of lucky guessing, with so few tasters, is too great. Even different websites come up with different results. Sometimes tests on the same website done at different times have different results. Sometimes tasters say they notice a hint of this hop or that grain and I have a hard time believing them. Especially if they already know what kind of beer it is.

Your comments indicate that you do not know how the triangle test or the statistical test behind it work. Google the chi-squared goodness-of-fit test and read up on inferential stats and what a P value is. There is always the chance of “lucky guessing” and that’s precisely why we use stats–to help us distinguish random chance–i.e. simply guessing– from a real effect.

Triangle tests and inferential stats and P values are definitely not perfect, but their imperfections lie more in how humans misinterpret and misunderstand them than in the tests themselves. And they are the best tools we have to try to objectively measure something that is very subjective, i.e. sensory perception.

They also depend on a very large number of testers to be accurate. Not 5-24. Maybe I am wrong, but the results I see are usually just slightly above or slightly below passing. Not really inspiring for so few testers. Still interesting.

I know exactly what the “P” value is. You start by drinking 6 home brews. On the way to the bathroom, or tree, you do the calculations. 6 brews x cost of $1.00/ homebrew = P where P=cost of drinking those beers.

Richard, I’m not a sensory professional, but the claim that the triangle test, even with small numbers of tasters, is reliable is well-supported in the literature. For example, see

https://www.apps.fst.vt.edu/extension/enology/downloads/wm_issues/Sensory%20Analysis/Sensory%20Analysis%20-%20Section%204.pdf

Please provide additional support for your claim.

@richard

Bro, you’re missing a critical point: the so-called alpha test, which is what the Brulosophy-Brothers employ. They claim statistical significance when the probability that the results came from “lucky guessing” is 5% or less. That means that the probability that it *wasn’t* lucky guessing is at least 95%!

Maybe so, but I don’t believe it for a second. Only 5% guessing? I don’t think so. Now if you turn it around and say 95% guessing, I would be more inclined to believe you.

The article you referred me to is for Wine Tasting and the use Trained Tasters. Also, the chart included for Triangle Testing specifies for single tasting, 4/5, 5/6, 5/7 and 6/8 correct responses are required to be deemed accurate. Some of there tests include partially rotted fruit vs regular fruit in the wine making. Doesn’t seem relevant.

Also beer is quite different from wine, especially since the Beer Testers are not trained and often are, like me, just simple beer drinkers.

I still thing guessing plays a very large part of the results.

It is easy to form a belief and then dig in on that belief. When I searched for triangle test information, I found plenty of literature. Be curious. You have much of the world’s knowledge at your fingertips. You can report back with a more persuasive argument.

Actually, I would rather sit back, enjoy the Florida heat and sip on my home brew.

Apparently a side effect of Florida heat is that it destroys critical thinking skills :-O

That could be, but it enhances the love of drinking a cold home brew.

I’m late at discussion, anyway, besides the bad, BAD mood of Richard, I kind got his point. These triangle tests has a low sample. That’s a fact that could lead to distortions. One major issue is that the “guessers” HAVE to choose. In some exbeerment’s results, they don’t know the difference. So, if they don’t know the differences between the beers they’re tasting, that result shouldn’t be considered in the final result.

Anyway, it’s a nice topic and a good experiment, because too much homebrewers advocate for DH, but if you clean out the natural biases, you can found in these experiments that there isn’t a huge difference between hop stand and dry hopping. Paul got 2 out of 5!

In fact, some prefer hop stand, mainly because it drive off the myrcene. They even create a new technic to do it. It’s called dip hopping. Maybe, it’s the major issue with heavy dry hopping, all tastes citrus forward.

For me, it’s easier to do a hop stand!

Cheers!

Alan, Nice reply and you make some good points. I am not in a BAD mood. I just can’t take the results of these tests seriously and I am not sure why anyone does. As I said before though, I really enjoy reading about the experiments and I do learn something from most of them. I do look forward to seeing what is new. (Even if I don’t always agree with the results)

Good xbmt! When you do your hop stand, are the hops in a hop spider or are they just thrown into the kettle? I’m asking because I don’t seem to get much hop aroma putting the hops in the spider. Thanks in advance for the info.