Author: Paul Amico

Fermentation is the seemingly magical part of the brewing process where yeast convert sugary wort into alcohol and carbon dioxide (CO2), thus turning it into the much beloved beverage called beer. Whereas modern brewers, aware of the negative impact certain microorganisms can have, tend to keep their fermentation vessels sealed, open fermentation was commonplace among brewers in a number of historical brewing regions.

As the name suggests, open fermentation involves fermenting beer in an unsealed vessel where the top is exposed to the environment. In addition to allowing for easy yeast harvesting, this method is purported to encourage the development of certain esters and phenols while also allowing undesirable fermentation byproducts to readily off-gas. Some have even claimed that the lack of backpressure in an open vessel leads to less yeast stress and thus healthier fermentations overall.

Of the hundreds of batches I’ve brewed over the years, I’ve never attempted an open fermentation, as my concern about oxidation has always outweighed my curiosity. However, with a couple past xBmts indicating open fermentation may have an impact on more characterful beer styles, I began to wonder how it might affect an American Pale Ale and put it to the test!

| PURPOSE |

To evaluate the differences between an American Pale Ale fermented in a closed vessel and one fermented in an open vessel.

| METHODS |

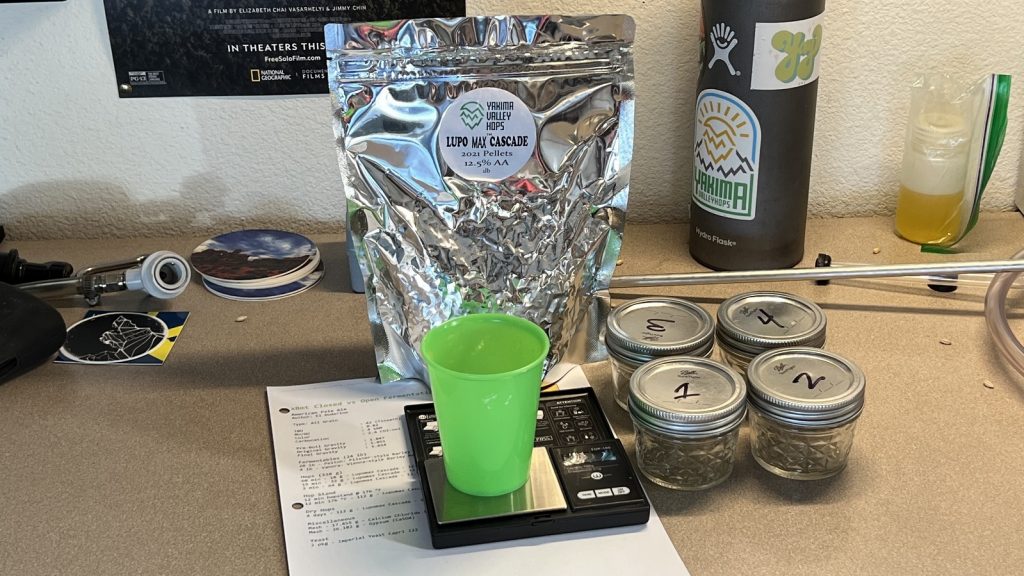

For this xBmt, I designed a simple American Pale recipe using the LUPOMAX version of one of my favorite hop varieites.

Blunted Affect

Recipe Details

| Batch Size | Boil Time | IBU | SRM | Est. OG | Est. FG | ABV |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5.5 gal | 60 min | 40.8 | 5.7 SRM | 1.054 | 1.008 | 6.04 % |

| Actuals | 1.054 | 1.008 | 6.04 % | |||

Fermentables

| Name | Amount | % |

|---|---|---|

| Lamonta: Pale American Barley Malt | 10 lbs | 83.33 |

| Vanora: Vienna-style Barley Malt | 2 lbs | 16.67 |

Hops

| Name | Amount | Time | Use | Form | Alpha % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cascade LUPOMAX | 10 g | 50 min | Boil | Pellet | 12.5 |

| Cascade LUPOMAX | 11 g | 25 min | Boil | Pellet | 12.5 |

| Cascade LUPOMAX | 19 g | 8 min | Boil | Pellet | 12.5 |

| Cascade LUPOMAX | 66 g | 10 min | Aroma | Pellet | 12.5 |

| Cascade LUPOMAX | 112 g | 4 days | Dry Hop | Pellet | 12.5 |

Yeast

| Name | Lab | Attenuation | Temperature |

|---|---|---|---|

| Capri (I22) | Imperial Yeast | 74% | 32°F - 32°F |

Notes

| Water Profile: Ca 92 | Mg 1 | Na 10 | SO4 153 | Cl 50 |

Download

| Download this recipe's BeerXML file |

I started off this brew day by collecting the full volume of filtered water for a single 10 gallon batch, which I adjusted to my desired profile.

After flipping the switch on my Clawhammer Supply 240v controller to get it heating up, I weighed out and milled the grain.

With the water properly heated, I incorporated the grains then turned on the pump to recirculate the sweet wort. When the hour long mash rest was complete, I hoisted the grains out of the kettle then set my controller to heat the wort up.

I then prepared the kettle hop additions.

The wort was boiled for 60 minutes with hops added at the times listed in the recipe, after which it was quickly chilled with my CFC during transfer to identical sanitized fermenters.

With a refractometer reading showing the wort was at my target 1.054 OG, I placed the fermenters in my chamber and pitched a pouch of Imperial Yeast I22 Capri into both batches.

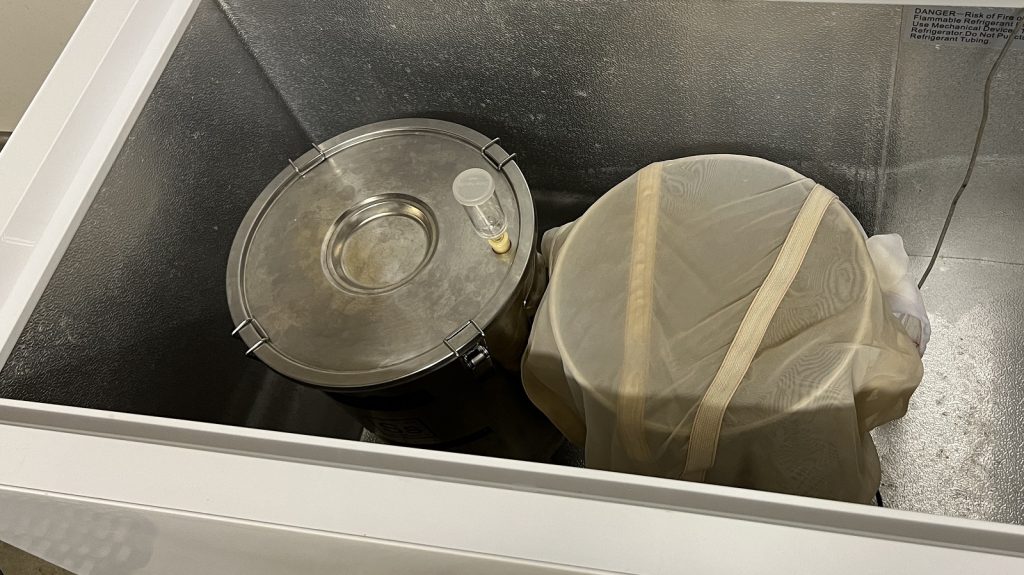

At this point, I sealed one fermenter and draped a sanitized Brew Bag over the other one.

The beers were left to ferment at 70°F/21°C for 6 days before I returned to add the dry hop additions.

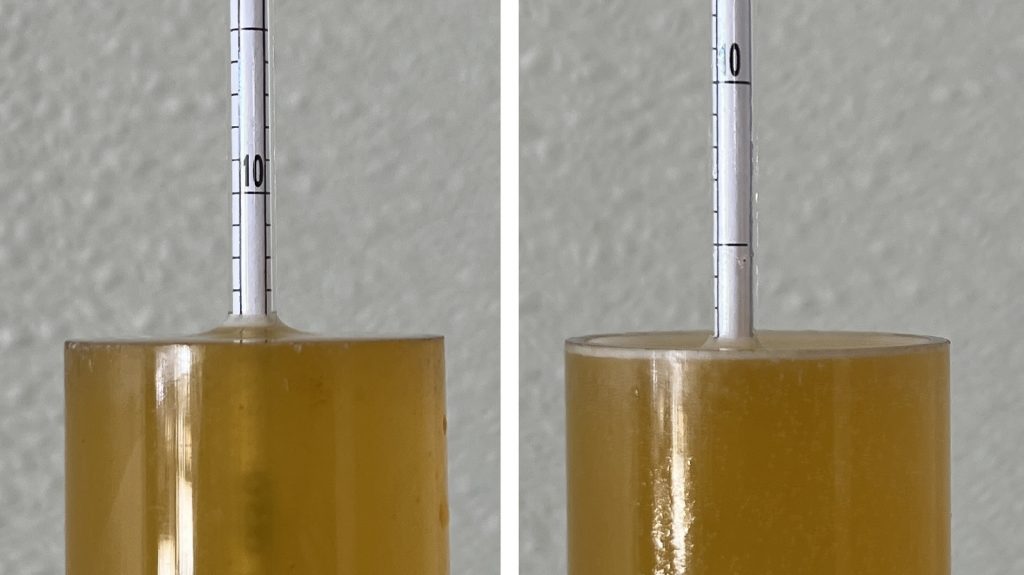

After another week, I took hydrometer measurements showing the open fermented beer finished 0.004 SG points higher than the beer fermented in the sealed vessel.

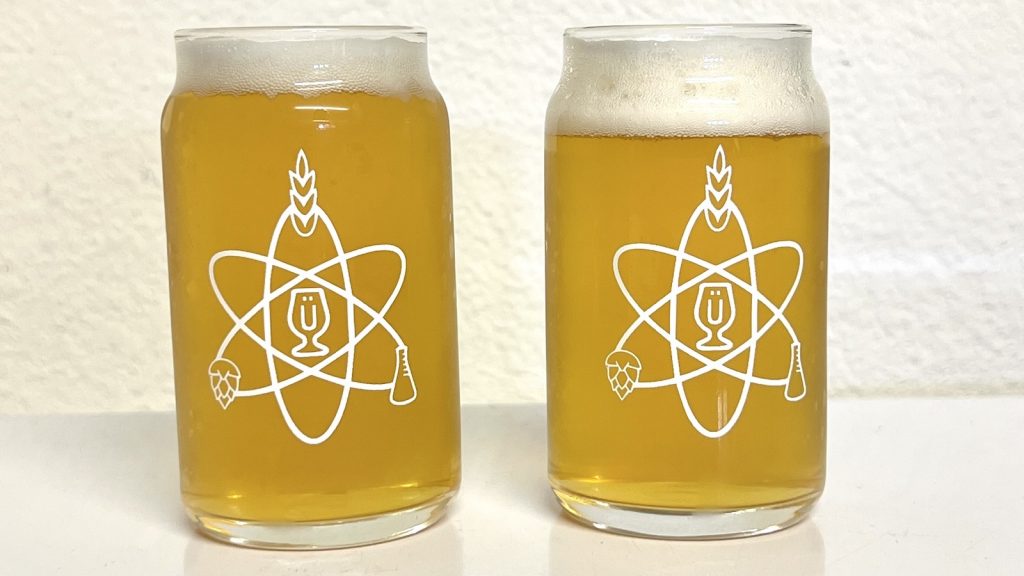

At this point, I proceeded with transferring the beers to CO2 purged kegs, which were placed in my keezer and burst carbonated overnight before I reduced the gas to serving pressure. After a week of conditioning, they were carbonated and ready for evaluation.

| RESULTS |

A total of 23 people of varying levels of experience participated in this xBmt. Each participant was served 1 sample of the beer fermented in a sealed vessel and 2 samples of the beer fermented in an open vessel in different colored opaque cups then asked to identify the unique sample. While 12 tasters (p<0.05) would have had to accurately identify the unique sample in order to reach statistical significance, only 7 did (p=0.69), indicating participants in this xBmt were unable to reliably distinguish an American Pale Ale fermented in a sealed vessel from one that was fermented in an open vessel.

My Impressions: Out of the 5 semi-blind triangle tests I attempted, I correctly identified the odd-beer-out 3 times, which isn’t consistent enough to indicate I could reliably tell them apart. I perceived these beers as having similar levels of classic Cascade hops character with a unique and tasty juiciness from the I22 Capri yeast.

| DISCUSSION |

Open fermentation is a practice that’s as old as brewing itself, and while the earliest brewers likely did it as a means of unwittingly inoculating wort with yeast, some modern brewers contend it has other benefits. Still commonly employed by brewers of traditional British, Belgian, and German ale, fermenting in open vessels is said to encourage the formation of esters and phenols appropriate in those styles. Interestingly, tasters in this xBmt were unable to reliably distinguish an American Pale Ale fermented in a sealed vessel from one that was fermented in an open vessel.

Considering past xBmts where tasters were able to distinguish open fermented Saisons and British Golden Ales from ones fermented in sealed vessels, while such was not the case in a similar comparison with Czech Premium Lager as well as this American Pale Ale, it seems plausible open fermentation has a larger impact when more characterful yeasts are used. However, there’s also the possibility something else is at play, for example, the hop character in this American Pale Ale being strong enough to cover up any differences caused by the fermentation environment. One of the more curious outcomes of this xBmt is that the closed fermentation beer had a higher FG than the batch fermented in a sealed vessel, as some posit backpressure actually leads to lower attenuation when using certain yeast strains.

Prior to this xBmt, I’d never performed an open fermentation, and given both these results as well as my own inability to tell these beers apart, I see no good reason to continue using this method, other than for future experimentation, of course. While I’m open to the idea that open fermentation can have a noticeable impact on certain types of beers, I’m happy enough with the beers I make in sealed vessels, which has the added benefits of reducing the risks of both contamination and oxidation.

If you have any thoughts about this xBmt, please do not hesitate to share in the comments section below!

Support Brülosophy In Style!

All designs are available in various colors and sizes on Amazon!

Follow Brülosophy on:

FACEBOOK | TWITTER | INSTAGRAM

If you enjoy this stuff and feel compelled to support Brulosophy.com, please check out the Support page for details on how you can very easily do so. Thanks!

10 thoughts on “exBEERiment | Impact Open Fermentation Has On An American Pale Ale”

I like the idea of this experiment but had a couple of thoughts about the implementation. In my experience, open fermentation “works” in certain (top cropping) strains due to exposure to oxygen. I know 1318 (Juice) is one, but when crossed with whatever Loki is (is it Voss?) does it maintain this top-cropping characteristic? And if the lid to that freezer was closed during the six days you said you left it alone, how rapidly does it get filled with CO2, converting your open vessel into a (7 cubic foot or whatever) closed one?

Why do the brewers almost always use 2 samples of one beer and 1 sample of the other beer? Seems like 2 samples of each beer would yield more Accurate results exponentially. It would eliminate most of the lucky guessing. I wonder if the brewers are afraid they would never get results they are looking for. Or would most testing be “inconclusive”. Still makes good reading though.

I wonder if the lower apparent attenuation of the open fermented batch might be attributable to the “apparent” part of the descriptor. By leaving the fermenter wide open to the air, you’re obviously allowing the beer to be exposed to more oxygen. With that oxygen, the yeast (subject to the impact of the Crabtree effect) could fully digest a larger portion of the sugars completely down to CO2, rather than leaving residual chunks of those sugars in solution as ethanol. If this is what really happened in the fermenter, than the yeast would have consumed the same amount of sugar (and thus had the same true attenuation), but by leaving slightly less low density ethanol in solution it would result in a higher finishing gravity.

Do I understand correctly that the open fermented batch remained fully exposed to the air the whole time, even after addition of the dry hop? If so, that certainly alleviates my concerns about opening a sealed fermenter for a few seconds to add a dry hop charge!

“this method is purported to encourage the development of certain esters and phenols”

Citation needed…

I started open fermenting my German Hefe Weizens in a 15 gallon sterilite container from wal mart. By far the best Hefe’s I’ve ever brewed.

69% of the respondents correctly chose the different beer. That IS statistically significant.

I beg your pardon. When nearly 70% of the panel can distinguish between the two beers, that is a significant number.

7/23 = 70%

Must be that new math.

7/23 is 30%. You’d expect 33% to randomly guess each option if they were all identical.

My error, misread the numbers.