Author: Steve Thanos

It’s often said that brewers make wort while yeast makes beer. Indeed, this incredible single-cell organism is responsible for turning the sugary liquid extracted from malt into the delicious beverage we all love, so it makes sense that brewers would be thoughtful about how they treat their yeast. One common method involves propagating yeast in a starter to ensure an adequate pitch rate, which reduces yeast stress and the potential for undesirable off-flavors.

The process for making a yeast starter is quite simple – make a relatively low OG unhopped wort using malt extract, chill it to room temperature, pitch the yeast, then throw it on a stir plate and leave it alone for a few days. Seeing as the goal of a starter is to increase cell counts, it’s usually recommended to keep the starter around 70°F/21°C, as any off-flavors produced will ostensibly be metabolized during the subsequent beer fermentation. Moreover, it’s been claimed that propagating yeast at cooler temperatures may actually be detrimental, reducing overall activity and growth such that the yeast underperform during beer fermentation.

Over the years, I’ve realized yeast are incredibly robust, capable of doing their job in less than hospitable environments. That being said, keeping yeast starters at room temperature is unarguably easier than keeping it cool, so that’s what I’ve always done. When recently chatting with other brewers, the topic of yeast starter temperature came up, and we all agreed that temperature isn’t anything to worry about. Of course, I held the thought in the back of my mind and ended up designing an xBmt to test it out for myself.

| PURPOSE |

To evaluate the differences between a Blonde Ale fermented with yeast from a starter that was held at 70°F/21° and one where the starter was held at 50°F/10°C.

| METHODS |

My hope being for any differences between the beers to be readily apparent, I went with a simple Blonde Ale recipe for this xBmt.

Anxious By Proxy

Recipe Details

| Batch Size | Boil Time | IBU | SRM | Est. OG | Est. FG | ABV |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5.5 gal | 60 min | 24.4 | 3.6 SRM | 1.06 | 1.01 | 6.56 % |

| Actuals | 1.06 | 1.01 | 6.56 % | |||

Fermentables

| Name | Amount | % |

|---|---|---|

| Pale Ale Malt | 9 lbs | 85.71 |

| Munich | 1.5 lbs | 14.29 |

Hops

| Name | Amount | Time | Use | Form | Alpha % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Centennial | 7 g | 60 min | Boil | Pellet | 10 |

| Sabro | 4 g | 30 min | Boil | Pellet | 14 |

| Amarillo | 7 g | 10 min | Boil | Pellet | 9.2 |

| Mosaic | 7 g | 10 min | Boil | Pellet | 12.3 |

| Amarillo | 7 g | 5 min | Boil | Pellet | 9.2 |

| Mosaic | 7 g | 5 min | Boil | Pellet | 12.3 |

| Sabro | 7 g | 5 min | Boil | Pellet | 14 |

Yeast

| Name | Lab | Attenuation | Temperature |

|---|---|---|---|

| Independence (A15) | Imperial Yeast | 76% | 32°F - 32°F |

Notes

| Water Profile: Ca 36 | Mg 12 | Na 9 | SO4 27 | Cl 17 |

Download

| Download this recipe's BeerXML file |

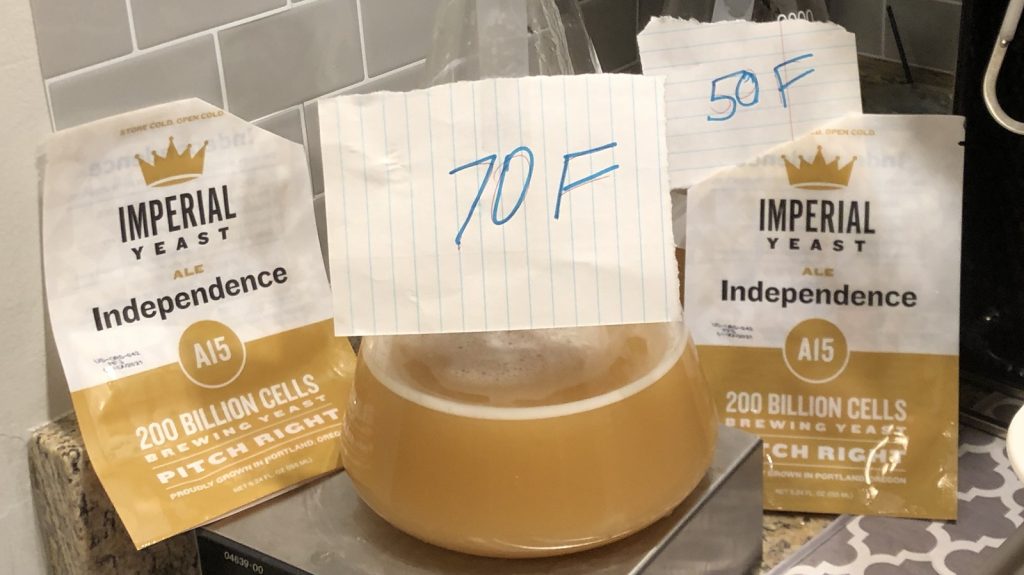

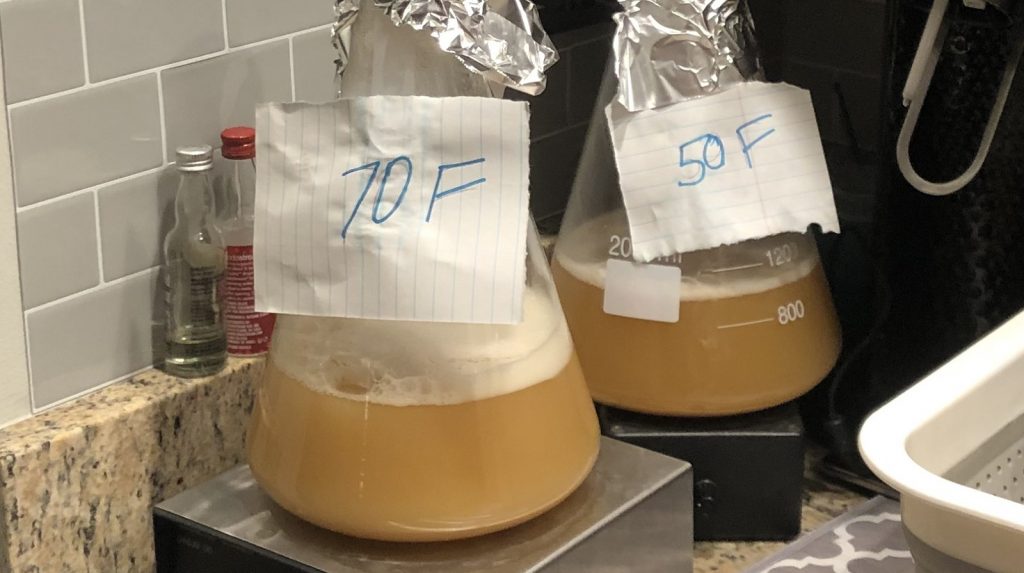

After making 2 equally sized yeast starters of Imperial Yeast A15 Independence a couple days ahead of time, I placed one on a stir plate in a spot that maintains a steady 70°F/21°C while the other was placed on a stir plate in my chamber set to 50°F/10°C.

After 10 hours, I briefly moved the cool starter for a comparison, after which it was placed back on the stir plate in my chamber. While the kräusen on the warm starter had larger bubbles and it seemed to be more active overall, the cool starter was certainly chugging along.

On brew day, I collected 2 sets of water, adjusted them to the same desired profile, then lit the flame under each, after which I weighed out and milled the grain.

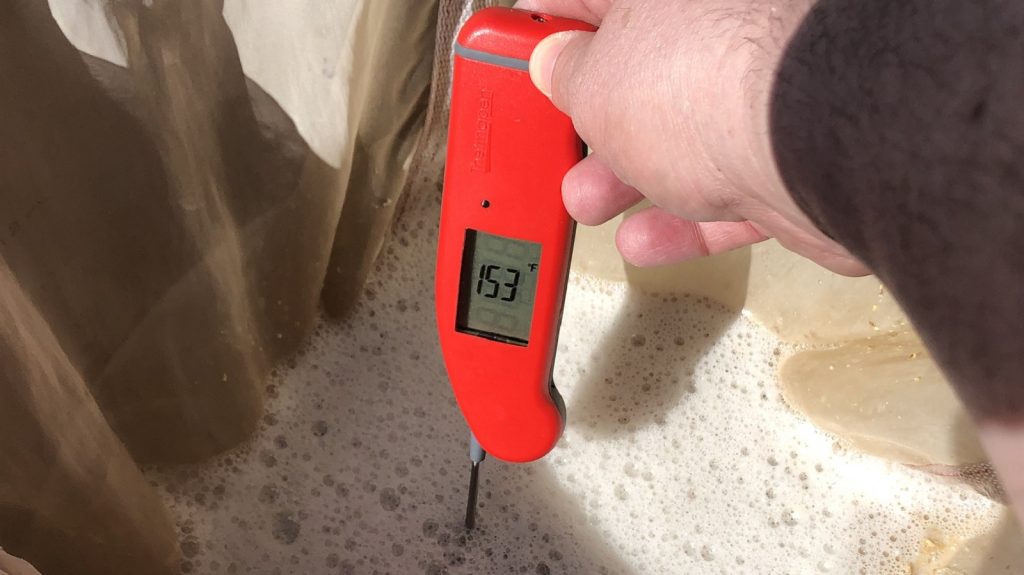

Once the water for each batch was adequately heated, I incorporated the grains then checked to make sure they were at my target mash temperature.

While the mashes were resting, I prepared the kettle hop additions.

Once each 60 minute mash was complete, I removed the grains then boiled the worts for 60 minutes before chilling them with my JaDeD Hydra IC.

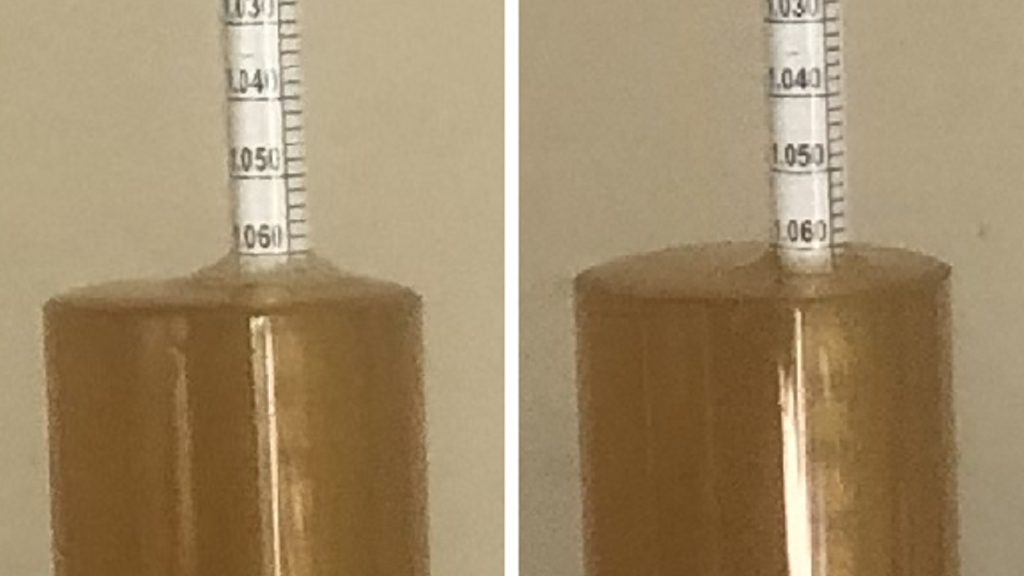

Refractometer readings showed both worts achieved the same 1.060 OG, a bit stronger than expected, which I thought might further accentuate the impact of the variable.

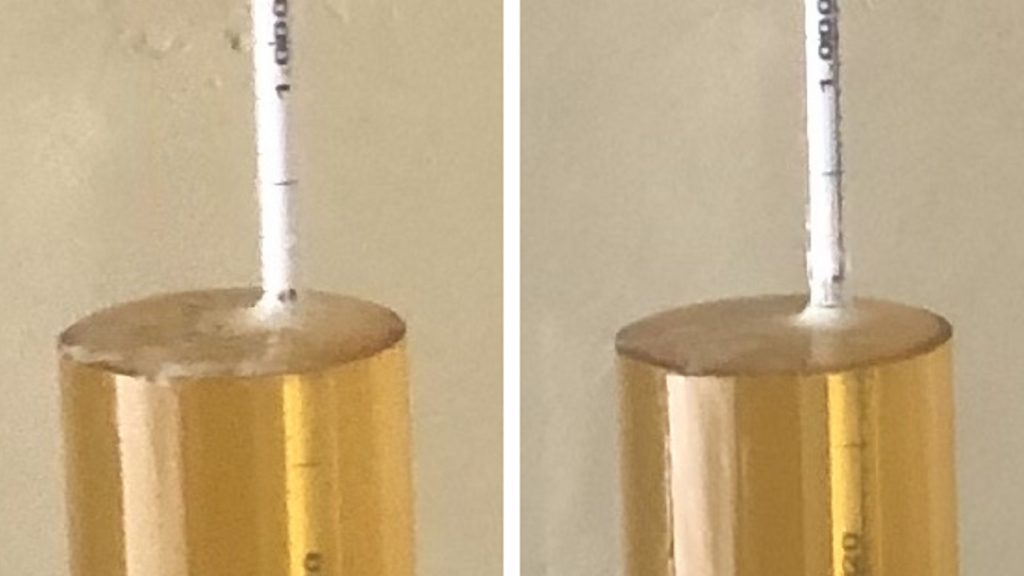

I racked identical volumes of wort to separate fermenters that were placed in my chamber and left to finish chilling to my desired fermentation temperature. When the beers were stabilized at 66°F/19°C a few hours later, I pitched the yeast starters. When I came back the following day, both seemed to be fermenting with similar vigor and I noticed no further differences in activity. After 3 weeks, I took hydrometer measurements showing the beers had reached the target FG.

At this point, I transferred the beers to sanitized kegs and placed them in my keezer where they were left to condition for a week before they were ready to serve.

| RESULTS |

Huge thanks to the Brewers of South Suburbia (BOSS) for allowing me collect data at a recent meeting held at Werk Force Brewing Company. A total of 24 people of varying levels of experience participated in this xBmt. Each participant was served 1 sample of the beer fermented with yeast from a starter that was held at 70°F/21° and 2 samples of the beer where the starter was held at 50°F/10°C in different colored opaque cups then asked to identify the unique sample. While 13 tasters (p<0.05) would have had to accurately identify the unique sample in order to reach statistical significance, only 6 did (p=0.86), indicating participants in this xBmt were unable to reliably distinguish a Blonde Ale fermented with yeast from a starter that was held at 70°F/21° and one where the starter was held at 50°F/10°C.

My Impressions: Out of the 5 semi-blind triangle tests I attempted, I correctly identified the odd-beer-out just once. These beers were identical in every way, both displaying a doughy malt flavor with subtle hop presence and clean fermentation profile.

| DISCUSSION |

Given the role yeast play in the production of beer, it makes sense that brewers would be concerned about keeping them as happy as possible, which usually involves propagation in a starter to ensure adequate pitch rates. Most brewers accept that starters can and perhaps should be held at warmer temperatures, as cooler environments can reduce the overall activity of yeast and increase stress, leading to potential off-flavors. Curiously, tasters in this xBmt were unable to distinguish a Blonde Ale fermented with yeast from a starter that was held at 70°F/21° and one where the starter was held at 50°F/10°C.

There’s little question yeast performance is impacted by temperature, and that warmer environments are more favorable for replication. In considering explanations for these results, it’s possible the potential negative impact of the cooler temperature was mitigated by the starting viability of the yeast, as Imperial Yeast pouches are known to contain 200 billion cells. Still, it may very well be that 50°F/10°C simply isn’t cool enough to increase yeast stress such that it impacts performance.

Personally, I’ve never felt compelled to hold yeast starters at anything other than room temperature, as tossing a flask on my counter is just easier. However, there have been times I’ve considered leaving a starter in an area of my house that stays a bit cooler during the Midwest winters, and these results lead me to believe it may not be nearly as detrimental as I previously believed.

If you have any thoughts about this xBmt, please do not hesitate to share in the comments section below!

Support Brülosophy In Style!

All designs are available in various colors and sizes on Amazon!

Follow Brülosophy on:

FACEBOOK | TWITTER | INSTAGRAM

If you enjoy this stuff and feel compelled to support Brulosophy.com, please check out the Support page for details on how you can very easily do so. Thanks!

6 thoughts on “exBEERiment | Impact Yeast Starter Temperature Has On A Blonde Ale”

I’m not usually one to complain about these free-to-me experiments, but it’s too bad this wasn’t done with White Labs yeast. Does an allegedly 200B cells even completely double in number in what appears to be a 1L starter volume? Making it two days ahead allows for the one that will be replicating slower in the cold to have plenty of time to catch up to the room temperature one in terms of the minimal replication that’ll be going on in the small starter (though I realize that the hypothesis was that cold=stress, not that cold=slower cell cycle). Beer sounds good though!

A yeast count of each starter prior to pitch? That would be the test most useful (to my mind) of any real difference here. Interesting piece (as ever!). Perhaps a starter temperature experiment with lager yeast in a lager ferment might be more conducive(?). Just a thought. I too will continue to leave my starters at room temp to ensure max yeast growth in the time prior to pitch😉

Greetings from Greece island Chios, your articles are university.If you want Chios mastic for experiment send me an address.

Tryfon,

Let’s chat! Email me at Steve@beerconnoisseur.local

When using yeast starters I’ve heard conflicting opinions on pitching the supernatant verses dumping it and only pitching the yeast cake. The claim is that the supernatant may impart off flavors in the beer. Which way did you pitch your starter?

Check this xBmt out.