Author: Steve Thanos

Simple sugar is a brewing ingredient typically used to increase the strength of a beer without having much of an impact on its perceptible qualities, as it is essentially 100% fermentable. One of the most common simple sugars is sucrose, or table sugar, a disaccharide made up of one glucose molecule and one fructose molecule that are easily metabolized by yeast. While easily accessible and rather inexpensive, modern brewers have been looking to other sugars sources as a means of creating uniquely flavored beers.

Extracted from a small melon grown in Southeast Asia, monk fruit sugar is gaining popularity in the United States as a healthier alternative to sucrose, as it’s an all-natural sweetener that possesses zero calories, plus it’s markedly sweeter. While some have reported success using monk fruit sugar as a back-sweetener, it has yet to be readily embraced by brewers, possibly due to the fact it’s said to be non-fermentable.

In the few years I’ve been using monk fruit sugar for cooking and baking, I’ve not noticed much of a perceptible difference between it and sucrose. As someone who enjoys experimenting with new ingredients, I was curious of what impact using monk fruit sugar in a beer would have and designed an xBmt to test it out for myself!

| PURPOSE |

To evaluate the differences between an American Pale Ale made with sucrose and one made with an equal amount of monk fruit sugar.

| METHODS |

For this xBmt, I went with my house American Pale Ale recipe, swapping out a portion of the pale malt for either type of sugar.

Self-Righteous Pale Ale

Recipe Details

| Batch Size | Boil Time | IBU | SRM | Est. OG | Est. FG | ABV |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5.5 gal | 60 min | 46 | 4.8 SRM | 1.055 | 1.013 | 5.51 % |

| Actuals | 1.055 | 1.013 | 5.51 % | |||

Fermentables

| Name | Amount | % |

|---|---|---|

| Pale Malt | 8.5 lbs | 85 |

| Sucrose OR Monk Fruit Sugar | 1 lbs | 10 |

| Caramel Malt 10L | 8 oz | 5 |

Hops

| Name | Amount | Time | Use | Form | Alpha % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cashmere | 20 g | 60 min | Boil | Pellet | 8.5 |

| Centennial | 14 g | 20 min | Boil | Pellet | 10 |

| Vic Secret | 40 g | 5 min | Boil | Pellet | 15.5 |

Yeast

| Name | Lab | Attenuation | Temperature |

|---|---|---|---|

| Flagship (A07) | Imperial Yeast | 77% | 32°F - 32°F |

Notes

| Water Profile: Ca 40 | Mg 13 | Na 9 | SO4 10 | Cl 14 |

Download

| Download this recipe's BeerXML file |

After collecting 2 identical volumes of and adjusting them to my desired mineral profile, I began heating them up before weighing out and milling the grain.

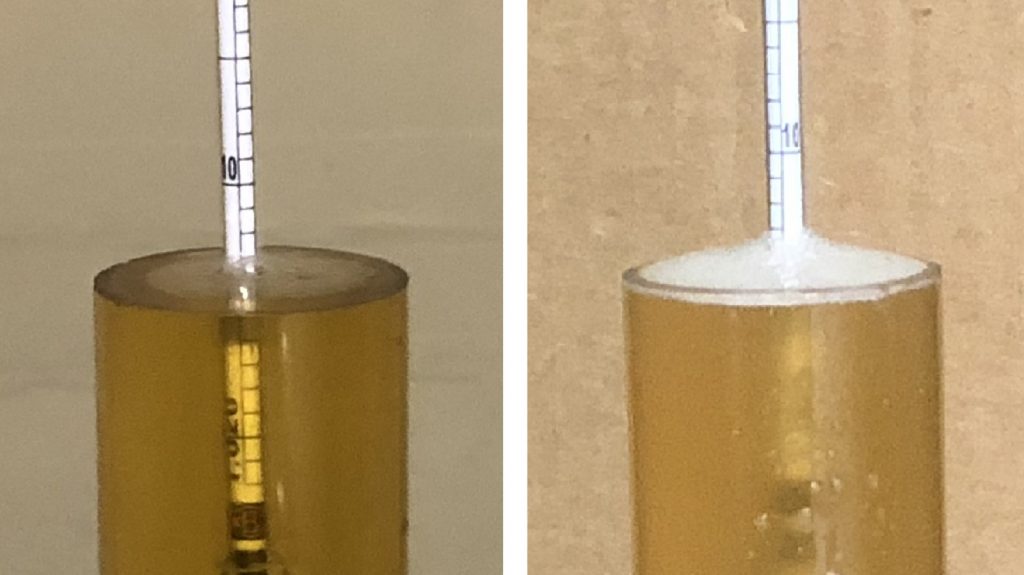

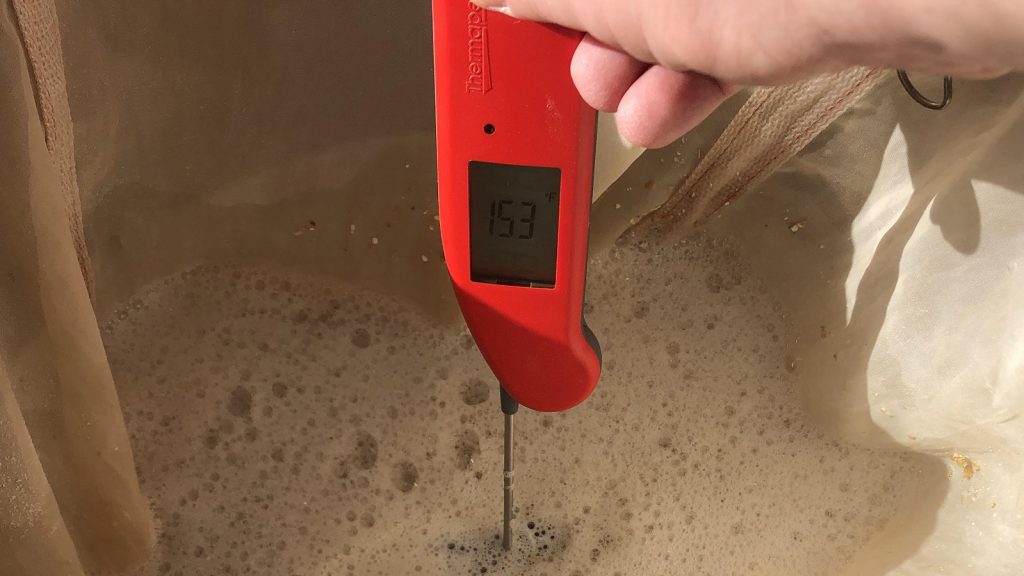

Once the water for each batch was adequately heated, I incorporated the grains then checked to make sure they were at my target mash temperature.

While the mashes were resting, I prepared the kettle hop additions.

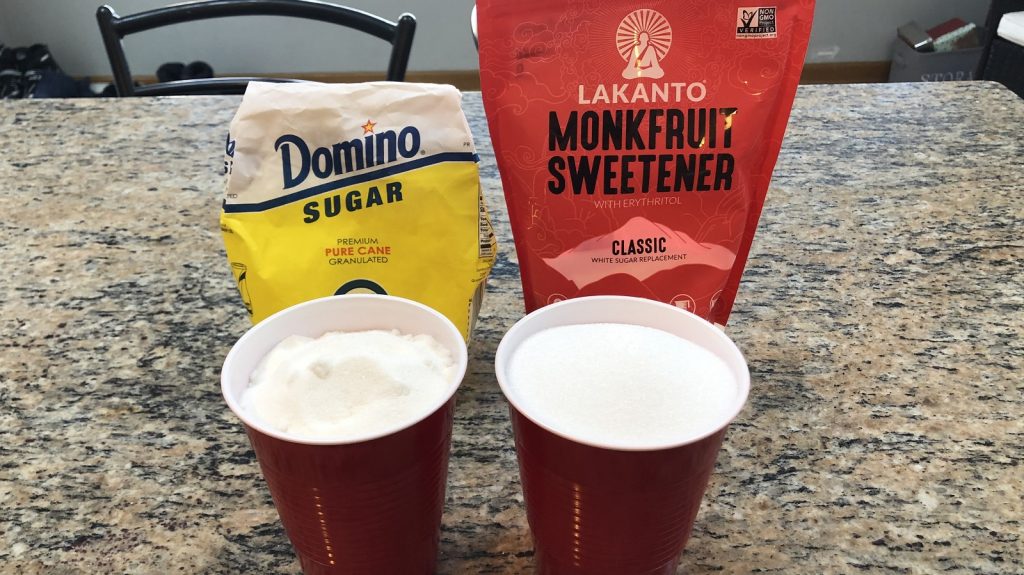

At this point, I weighed out identical amounts of sucrose and monk fruit sugar.

Once each 60 minute mash was complete, I removed the grains, added the different types of sugar to their respective wort, then boiled each for 60 minutes before quickly chilling them with my IC.

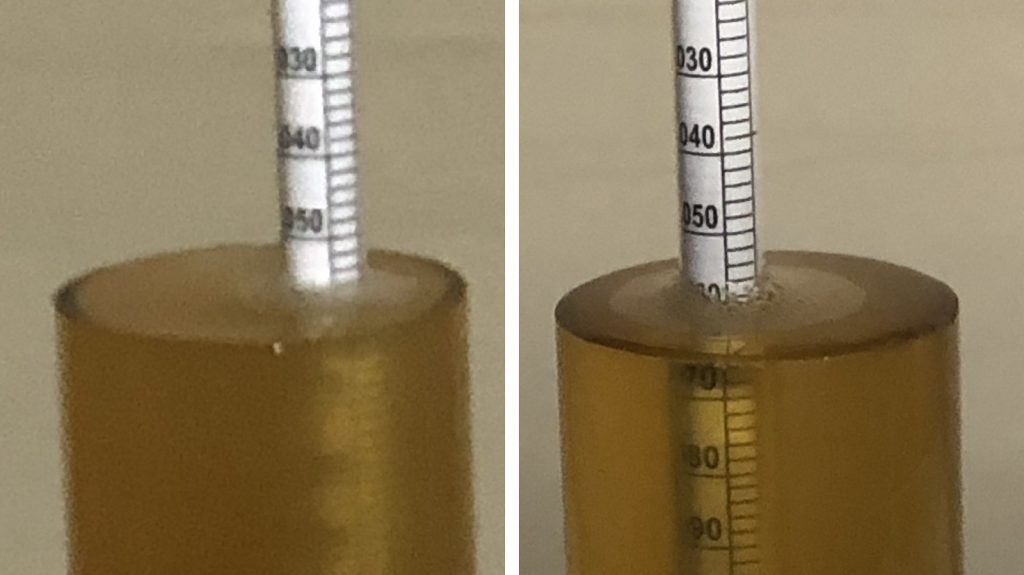

Hydrometer readings showed sucrose wort was a couple SG points lower than the one made with monk fruit sugar.

The filled carboys were placed in my chamber and left to finish chilling to my desired fermentation temperature of 66°F/19°C for a few hours before I pitched a pouch of Imperial Yeast A07 Flagship into each.

With activity noticeably absent 3 weeks later, I took hydrometer measurements showing a small difference in FG.

At this point, I transferred the beers to sanitized kegs and placed them in my keezer where they were left on gas for 2 weeks before they were ready for evaluation.

| RESULTS |

Massive thanks to the awesome crew at Werk Force Brewing for letting me collect data at their establishment, as well as all of their fine customers! A total of 31 people of varying levels of experience participated in this xBmt. Each participant was served 2 samples of the beer made with sucrose and 1 sample of the beer made with monk fruit sugar in different colored opaque cups then asked to identify the unique sample. While 16 tasters (p<0.05) would have had to accurately identify the unique sample in order to reach statistical significance, only 9 did (p=0.75), indicating participants in this xBmt were unable to reliably distinguish an American Pale Ale made with 1 lb/0.45 kg of sucrose from one made with the same amount of monk fruit sugar.

My Impressions: Out of the 5 semi-blind triangle tests I attempted, I correctly identified the odd-beer-out only 2 times. To my palate, both beers had the same biscuit malt flavor with pleasing hop character that made them very easy to drink.

| DISCUSSION |

While frowned upon by some traditionalists, adding a dose of simple sugar to a batch of beer is an excellent way to boost its strength while having minimal flavor impact. While sucrose is one of the most popular options due to its ease of access and price, there are some unique alternatives including monk fruit sugar, which is characteristically different in a number of ways. Interestingly, tasters in this xBmt were unable to reliably distinguish an American Pale Ale made with sucrose from one made with the same amount of monk fruit sugar.

In addition to low calorie sweeteners generally tasting different than the table sugar they emulate, most are also non-fermentable, hence their use as back-sweeteners. However, monk fruit sugar is widely believed to be a decent flavor analogue of sucrose, even when blended with erythritol, which may help to explain these results. Curiously, the apparent attenuation of the sucrose beer was just 0.9% higher than that of the batch made with monk fruit sugar, which was unexpected considering the amount of sugar used.

Given my personal experience using monk fruit sugar in cooking, I admittedly didn’t expect these beers to taste drastically different, though I was surprised by their similar levels of attenuation. I’m no chemist, but if monk fruit sugar really is zero calorie, that would amount to approximately 37 fewer calories per pint of this American Pale Ale, which seems rather substantial. It’s price inarguably poses a major barrier for mass adoption by brewers, but I certainly look forward to experimenting more with monk fruit sugar in the future.

If you have any thoughts about this xBmt, please do not hesitate to share in the comments section below!

Support Brülosophy In Style!

All designs are available in various colors and sizes on Amazon!

Follow Brülosophy on:

FACEBOOK | TWITTER | INSTAGRAM

If you enjoy this stuff and feel compelled to support Brulosophy.com, please check out the Support page for details on how you can very easily do so. Thanks!

13 thoughts on “exBEERiment | Sugar Additions: Sucrose vs. Monk Fruit Sugar In An American Pale Ale”

Assuming your mashes resulted in truly identical sugar compositions, it looks like you just confirmed that that particular monk fruit formulation is somewhat fermentable. Someone on Reddit tried fermenting a number of artificial sweeteners and your monk fruit one went from 1.042 to 1.030 in their trial.

https://www.reddit.com/r/TheBrewery/comments/hltdpb/noncaloric_sweetener_test_results/?utm_source=share&utm_medium=ios_app&utm_name=iossmf

This isn’t surprising, since the Monkfruit sweetener contains glucose. Animals (and Humans as far as we know) aren’t able to use the glucose portions, but many microbes have the enzymes to cleave them off and use them. These experiments show that the yeast is able to use at least some of the glucose in Monkfruit.

If they both fully attenuated out, why would one possess less calories than another? There wouldn’t be residual sugar, and the .001 difference in final gravity isn’t 37 calories. Maybe I’m missing something.

In a typical beer, most of the unfermentable portion of the beer is carbohydrates that contribute calories. In the case of the monkfruit beer, it’s possible that some of that unfermentable portion is non-caloric. He’s getting that 37 calories figure from assuming the entirety of that pound of monkfruit sugar is calorie free. It’s possible that it’s both calorie free and fermentable by yeast, but it seems more likely that a portion is simple sugars

I would say you are exactly correct. the sugar itself may be non-digestible in mammals and hence have 0 calories. It looks however that it is fermentable, therefore converted to ethanol + CO2. The produced ethanol comes to ~7 kcal / gr.

I think there is a misunderstanding about this sweetener and “zero-calorie” sweeteners in general.

First, if your gravities both decreased by the same amount, the indication is that both worts were similarly fermentable.

Second, though this sweetener may have fewer calories than a comparable amount of table sugar eaten as-is, once fermented, it would be turned into CO2 and alcohol just the same, so the final beer would not have fewer calories. The “37 fewer calories” would not hold through to the final beer if the non-sugar sweetener was indeed fermented.

Third, “zero-calorie” sweeteners generally work either by being completely indigestible or by being much sweeter than sugar so that less of it can be used. In this case, the main ingredient of that product is erythritol, a sugar alcohol that actually is digestible and does have caloric value, albeit less than normal sugar. The second ingredient is monk fruit extract, which is mainly sweet because of mogrosides. Mogrosides are non-sugar molecules that are perceived as somewhere around 300 times sweeter than normal sugar, so way less can be used. Use of these sweeteners results in fewer calories for the same amount of sweetness.

Thank you so much for this explanation and clarification!

Aren’t you comparing apples and tomatoes here? The addition of sucrose, which is completely fermentable and does not add flavor, against monk fruit sugar, which is not supposed to be fermentable, and would add sweetness?

I posted a comment earlier, but it didn’t show up.

Monk Fruit extract (Mogrosides) actually contain glucose, but animals (probably including humans) are unable to use this sugar even though it tastes sweet.

However, it is known that microbes can cleave off the sugar and use it for energy. So that fact that the yeast can use it is not surprising. The erythritol component is essentially nonfermentable. So the small difference in attenuation probably results from that.

I just wanted to clarify that glucose itself is definitely used by and is the main energy source of humans. However in this instance (as Christopher Hamilton notes) the glucose molecules are stuck on to a bigger molecule and people cannot break them apart to absorb that sugar. Yeast seemingly can based on the attenuation here and so they are utilizing those sugars to make alcohol. Which ends up with the same type of caloric contribution as any other sugar.

The magrosides (the bigger molecule that has the glucose moiety) are by mass a relatively minor part of the monk fruit sweetener. The label lists each 8g serving has containing 8g of “sugar alcohols,” which would be the erythritol and is completely different from glucose. Accounting for rounding, this suggests that less than a half gram of the sweetener is magrosides, and even if the magrosides were 0.5 g per serving and fully fermentable this would make the sweetener just 6.25% fermentable. Thus fermentation of the magrosides does not explain the near-identical apparent attenuation of the two beers.

I can’t help but wonder, based on the apparent fermentation of a sweetener that is alleged to be non-fermentable, if perhaps Steve purchased his monkfruit sweetener online and unfortunately fell prey to a counterfeiter that is selling table sugar in monkfruit packaging.

I also use a product called Monk Sweet in cooking. It is blend of Erythritol, Stevia and Monk Fruit Extract. I’m interested in trying it to back sweeten a stout or other malty beer. Since you mentioned the interest in back sweetening why did you choose a rather dry beer style?

I am thinking of using monk sweet as a non-fermentable vegan sweetener in a beer I am brewing, together with regular sugar right before bottling. Does this mean I am risking bottle bombs and extra gravity by doing that? After what I have heard it’s non-fermentable, and should be an option instead of lactose