This xBmt was completed by a member of The Brü Club in collaboration with Brülosophy as a part of The Brü Club xBmt Series. While members who choose to participate in this series generally take inspiration from Brülosophy, the bulk of design, writing, and editing is handled by members unless otherwise specified. Articles featured on Brulosophy.com are selected by The Brü Club leadership prior to being submitted for publication. Visit The Brü Club Facebook Group for more information on this series.

Author: Alex Shanks-Abel

During the growth phase of fermentation, yeast require oxygen in order to replicate, after which it exclusively engages in anaerobic fermentation until the beer is ready to be packaged. From this point forward, exposure to oxygen can be quite detrimental, quickly leading to staling of beer and reduced shelf-life. While there are various mechanical options for minimizing cold-side oxidation when kegging, bottle conditioning poses more difficulties.

The typical bottling process involves transferring the fermented beer from one vessel to a bottling bucket, where it gets combined with priming sugar, then from the bucket to empty bottles, introducing 2 vectors for oxygen exposure. One proposed method for reducing the risk of oxidation involves adding a small amount of sulfite prior to bottling, though one concern is that this may hinder the yeast from metabolizing the priming sugar, resulting in poor carbonation.

Given the small amount of sulfite recommended for reducing cold-side oxidation, I began to wonder if it’s a feasible option when bottle conditioning. With several xBmts showing positive results when metabisulfite is added to kegged beer at packaging, I decided to see how things would pan out with a bottle conditioned beer.

| PURPOSE |

To evaluate the differences between a Kölsch-style beer dosed with PMB at bottling and one that it not dosed with PMB at bottling.

| METHODS |

For this xBmt, I went with a simple SMaSH Kölsch recipe with the goal of accentuating the variable.

Eau de Köln

Recipe Details

| Batch Size | Boil Time | IBU | SRM | Est. OG | Est. FG | ABV |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3.5 gal | 30 min | 21.7 | 3 SRM | 1.049 | 1.015 | 4.46 % |

| Actuals | 1.049 | 1.015 | 4.46 % | |||

Fermentables

| Name | Amount | % |

|---|---|---|

| Pelton: Pilsner-style Barley Malt | 6 lbs | 100 |

Hops

| Name | Amount | Time | Use | Form | Alpha % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hersbrucker | 43 g | 30 min | First Wort | Pellet | 3.2 |

Miscs

| Name | Amount | Time | Use | Type |

|---|---|---|---|---|

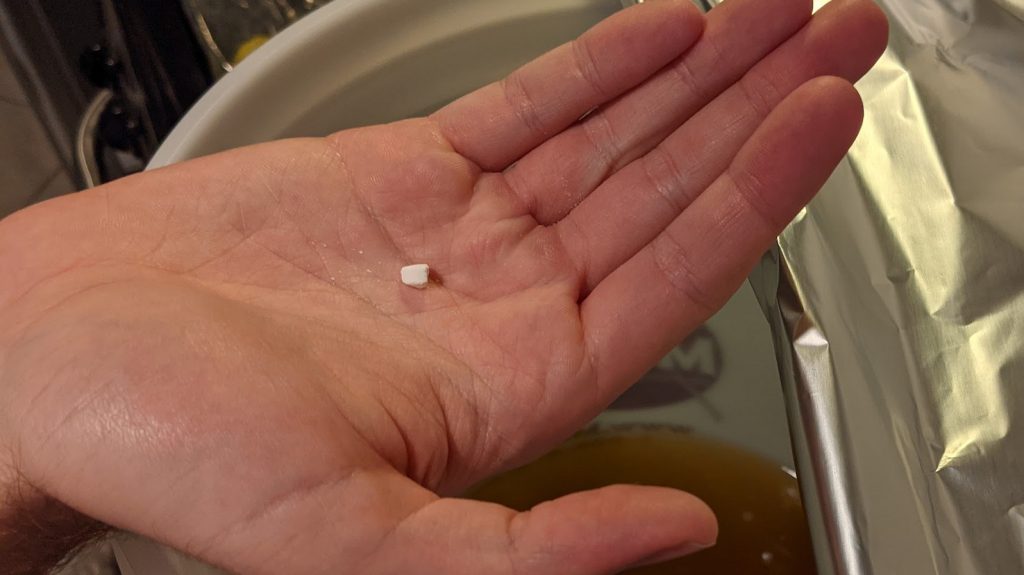

| Potassium Metabisulfite (K2S2O5) | 0.12 g | 0 min | Bottling | Water Agent |

Yeast

| Name | Lab | Attenuation | Temperature |

|---|---|---|---|

| Koln | LalBrew | 75% | 32°F - 32°F |

Notes

| Water Profile: Ca 48 | Mg 0 | Na 0 | SO4 73 | Cl 59 |

Download

| Download this recipe's BeerXML file |

After collecting the full volume of water for this 3.5 gallon/13.25 liter batch, I weighed out and milled the grains.

With the water properly heated, I added the grains and gave it a good stir.

I then checked to make sure the mash was at my target temperature of 162°F/72°C.

Following an extended overnight mash rest, I removed the grains then proceeded to boil the wort for 30 minutes.

A post-boil refractometer reading showed the wort was right at my intended 1.049 OG.

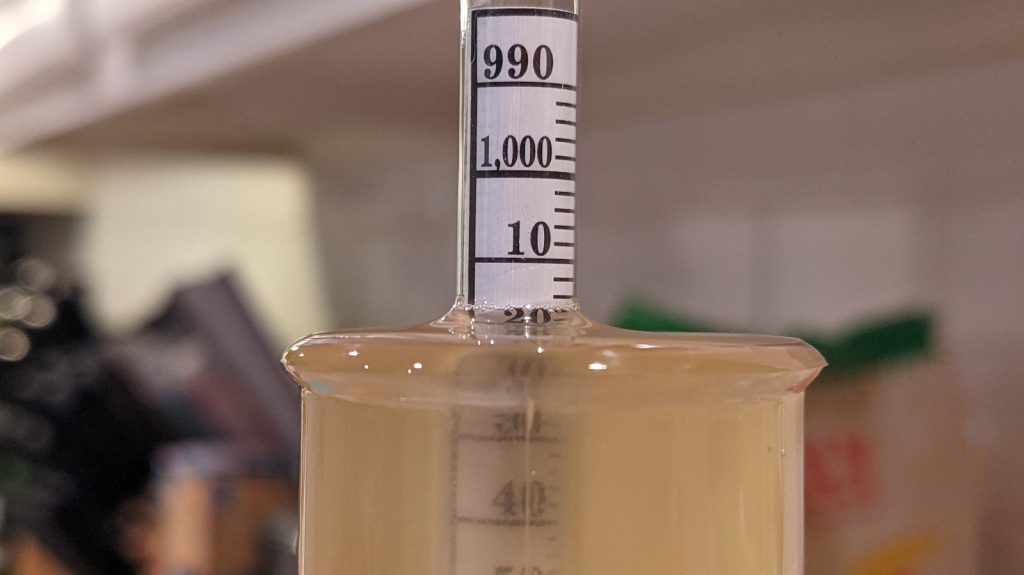

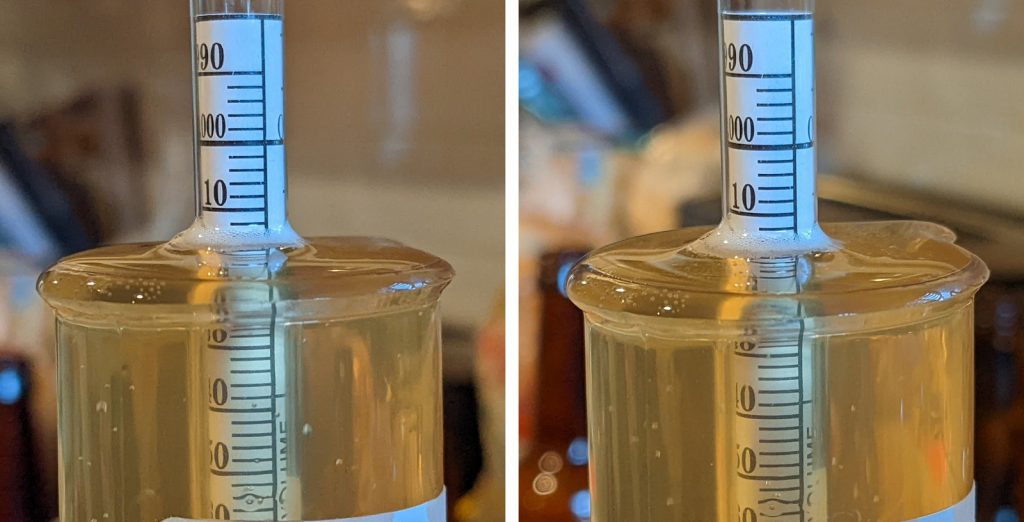

At this point, I transferred the hot wort to a stainless 5 gallon/19 liter keg and left it in a cool water bath to finish chilling overnight before I pitched a single pack of LalBrew Köln yeast. The beer was left to ferment in a cool water bath that maintained a steady 66°F/19°C for a week before I took hydrometer measurements showing both were at the same 1.015 FG.

At this point, I racked the beer to a bottling bucket and integrated the priming sugar. Once approximately half of the beer had been packaged, I added 0.12 grams of PMB.

Each bottle was labeled and placed in a box.

After conditioning for 3 weeks in a warm closet, I opened a bottle each to find both were adequately carbonated. Out of curiosity, I took hydrometer measurements of each and was unsurprised to discover both were still at the same FG.

The bottles were placed in my fridge and allowed to chill for a few days before they were ready for evaluation.

| RESULTS |

Due to social distancing practices as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic, data for this xBmt was unable to be collected in our typical manner. As such, temporary adaptations were made involving the author completing multiple semi-blind triangle tests in as unbiased a way as possible.

Utilizing 4 opaque cups of the same color where 2 were inconspicuously marked, one set was filled with the non-dosed beer while the other set was filled with the beer dosed with PMB at packaging. For each triangle test, 3 of the 4 cups were indiscriminately selected, thus randomizing which beer was the unique sample for each trial. Following each attempt, I noted whether I was correct in identifying the unique sample. Out of the 10 semi-blind triangle tests I completed, I needed to identify the unique sample 7 times (p<0.05) in order to reach statistical significance, though I did so just 6 times (p=0.077), indicating my inability to reliably distinguish a Kölsch dosed with PMB prior to being bottle conditioned from one that did not receive PMB at packaging.

My Impressions: These beers were identical in every way to me, leaving me to guess on each triangle test attempt. I was actually shocked I happened to get it right 6 times! While a bit hazy, these beers were deliciously floral, fruity, and crisp.

| DISCUSSION |

There are few things more demoralizing than a delicious batch of beer that nosedives in quality after packaging, especially because there’s little that can be done to salvage oxidized beer. Reducing cold-side oxygen exposure is especially difficult for those who bottle condition due to it usually involving multiple transfers, though some have found that adding a small amount of potassium metabisulfite (PMB) reduces the risk of oxidation. My inability to reliably distinguish a Kölsch packaged without PMB from one where PMB was added prior to being bottled suggests any differences were minimal enough to be imperceptible to me.

Not all packaging is created equal. It’s possible my inability to consistently tell these beers apart speaks to the ability of yeast to scrub oxygen during bottle conditioning. If that’s the case, adding sulfites to beer at packaging may be overkill when bottle conditioning. I’m equally pleased that the pinch of PMB didn’t noticeably stress the yeast.

I’m curious if my bottling methods could be a factor here, as I don’t use a bottling wand and fill my bottles nearly to the brim. Unlike the stories I’ve read about from others, I’ve never had issues with cold-side oxidation, not even when bottle conditioning notably sensitive Hazy IPA. I’m now curious if using PMB would have a different impact for those who leave more headspace in their bottles. Regardless, given my history as well as the results of this xBmt, I’ll continue to eschew sulfites when bottle conditioning.

Alex Shanks-Abel is a certified shoddy brewer residing in Texas with their lovely spouse, a 3 1/2 legged mutt, and 22 banana plants. Upon receiving an extract kit on their 21st birthday, they discovered a new passion and have been obsessively brewing ever since. Alex geeks-out over the science of fermentation while trying to brew as unpretentiously (i.e. shoddy) as possible. When Alex isn’t brewing in bags, they’re DMing too many D&D games or publishing video game mods that nobody asked for.

Alex Shanks-Abel is a certified shoddy brewer residing in Texas with their lovely spouse, a 3 1/2 legged mutt, and 22 banana plants. Upon receiving an extract kit on their 21st birthday, they discovered a new passion and have been obsessively brewing ever since. Alex geeks-out over the science of fermentation while trying to brew as unpretentiously (i.e. shoddy) as possible. When Alex isn’t brewing in bags, they’re DMing too many D&D games or publishing video game mods that nobody asked for.

If you have any thoughts about this xBmt, please do not hesitate to share in the comments section below!

Support Brülosophy In Style!

All designs are available in various colors and sizes on Amazon!

Follow Brülosophy on:

FACEBOOK | TWITTER | INSTAGRAM

If you enjoy this stuff and feel compelled to support Brulosophy.com, please check out the Support page for details on how you can very easily do so. Thanks!

16 thoughts on “The Brü Club xBmt Series | Cold-Side Oxidation: Impact Adding Potassium Metabisulfite (PMB) At Packaging Has On A Bottle Conditioned Kölsch”

Three weeks seems a bit short for this experiment.

On the British homebrew forum (https://www.thehomebrewforum.co.uk/) someone did the same kind of test with oxygen scavinging caps. It also did not make a difference. But one of the conclusions was also that it is better to fill your bottles with only a minimal headroom (compression of gas should still be possible of course).

Personally, I do use a bottling wand. However, I do not immediately close my bottles. The cap (either crown cap or flip top) goes on loose for a quarter so that some oxygen is already driven off by CO2 escaping from the beer.

Actually, my whole bottling process is:

1. Wash bottles and rinse with metabisulfite solution, leak out and let dry

2. Rack into bottling bucket (+sugar+bottling yeast)

3. Fill bottles with bottling wand, put cap on loose

4. Wait for a quarter of an hour before sealing bottles

My beers keep for at least a year (but I would not keep them longer). Blonde beers stay blonde. No signs of oxidation.

That’s interesting! I’ve been on the fence about the cap-on-loose method, mainly because I use a bench capper.

My process is similar to yours, with a few differences

I also use a bottling wand and batch prime as you do.

I add 0.3g Sodium Metabisulphate to the bottling bucket once the beer is fully transferred.

I bottle into 750ml amber PET bottles with screw caps, all sanitized with Star San.

I fill bottles as normal with the wand, but squeeze them gently before screwing the caps on so that the beer level is right at the bottom of the bottle. I then carefully screw in the chat. This means there is effectively no headspace at bottling.

To account for the bottle squeeze, I use 12% more sugar for priming.

The second advantage of PET bottles being squeezable is I know when they are fully carbonated by squeezing them. After a few days they are usually popped out to their usual inflated shape, and fully carbonated two to three weeks after bottling day. A final advantage of the 750ml size as opposed to the usual 330ml is there’s half as many per brew!

I can’t think of much more I can do to eliminate oxygen at bottling. My beers last well in the bottle, retaining hip character long enough for me to drink and enjoy them all. So I consider my method effective for my needs.

First, thank you for the experiment and everything you and Brulosophy do. So – this isn’t a knock. But FYI you read a hydrometer by looking at the surface of the liquid, not the little bit that’s pulled up the side. That initial measurement, as an example, isn’t 1.015 but closer to 1.020.

TIL, thanks! There’s a reason I got a digital refractometer.

This completely depends on the hydrometer, with many hydrometers stating in their manuals to take the reading from the upper meniscus

Depends on the hydrometer. Some specify taking the measurement from the top of the meniscus.

Since you’ve already gone this far, you should save a couple of bottles and repeat with in a few months to see what impact time will have on your results. Cheers!

I greatly appreciate the experiment and write-up! Oxidation in the bottle is one of the things I like to mull over in my head without ever changing anything (because flushing with CO2 requires a lot of additional equipment).

Adding a chemical at packaging would be sufficiently simple to integrate in any process, but I’d prefer to go without it.

I bottle straight from the fermentor, thinking it would reduce the O2 ingress during bottling itself, though I’m not sure if that actually makes a significant difference. I’ve also started capping each bottle immediately after filling instead of going in batches – it takes a little bit longer, but not much, and I hope the CO2 degassing from the agitation replaces some air in the headspace. Again, it’s more of educated-guess-meets-susperstition, but I do feel like my beers hold up better after a couple of months.

Strangely, I also feel like the yeast strain makes a difference – I just had a Saison I made a year ago, and it was still crisp and fresh -, although that might also be attributed to positive aromas masking the signs of staling.

It’s often said that the yeast in suspension would quickly consume any oxygen that’s introduced into the liquid, but yeast metabolism is a complex thing and I’ve never seen any actual measurements of dissolved oxygen that would support this claim. I’d be curious to see those levels at packaging, then a couple of hours later and maybe again on the next day, possibly with and without fresh yeast added at bottling.

Either way, I believe the main enemy is the air in the headspace. That oxygen will slowly diffuse into your beer.

Alex,

Will you be re evaluating the remaining

Bottles at a later date?

Cool experiment.

I exclusively bottle, and have never brewed a NEIPA due to their sensitivity to oxidation and my assumption that I could not sufficiently limit oxygen ingress to prevent problems. I’ve thought about trying adding sulfite, but was too worried about knocking the priming yeast out to actually give it a try. Since you carbed up just fine in 3 weeks, I’m going to have to revisit my reluctance to throw in a little sulfite!

Firstly kudos for making a beer in ONE batch and splitting at the last minute to compare the variable.

The amount of experiments here where they look at something near the end of the process and start by making two beers side by side is poor experimental design. It hurts everytime I see one. Any home-brewed turned pro will tell you the difficulty in batch consistency, so keep things simple like you did. And if you want to use a shiny fancy dual HLT/FV then pool them and split at the end to rule out any differences that may have been accidentally introduced.

Arguably the SMB batch was left open to air/uncapped for longer, so I suppose you could have syphoned equally into two bottling buckets and bottled alternative bottles to keep timing the same, but you kept things reasonably similar here.

I did the same once with a NEIPA and didn’t spot any differences. I think if a beer is packaged well it won’t make a perceivable difference, if it’s packaged terrible then nothing will help either way, but maybe there is that middle point where addition of SMB can make the difference if O2 is kept below a certain level, I don’t know

A simple way for low oxygen bottling is use flip top bottles and next day loosen cap till CO2 filled foam spurts out purging the headspace then rinse and finish bottle conditioning so yeast activity scrubs remaining oxygen then keep at 4 degC till you want to drink it. I use this for high carb styles with 2 coopers carbonation drops per 500ml bottle and bottles still taste great after 3 months.

Been struggling a bit with oxidation in IPAs (not just the hazy kind). I bottle straight from the fermenter, having added sugar directly to the bottles and using a bottling wand. I fill to the top with the wand in the bottle, so it leaves abut an inch of headspace when the wand is removed. I’ve ready lately about some people foregoing the wand and filling all the way to the top, leaving no headspace, but other people say this is a sure fire way of getting bottle bombs. I don’t want to take a chance of a bottle blowing up in my hand…. Thoughts?

Filling to the brim will make bottle bombs. It has happened to me before I stepped up my game. A wand just doesn’t cut it. Really, you need a counter-pressure filler and have to “cap on foam”. This means your FV needs to be pressure capable to at least 12psi.

Unfortunately not clear on skimming to how much beer you added the 0.12g. Stating that clearly and giving a ppm would be really helpful.