Author: Jake Huolihan

Every beer style falls somewhere on the sweet/dry spectrum, a characteristic that’s viewed by many as being just as much a function of subjective perception as objective measurement. Indeed, ask any brewer what they’d expect from a beer that finishes with a low FG and they’ll almost certainly use the term “dry,” whereas a higher FG is associated with sweetness.

While there’s no denying the impact of certain ingredients, brewers commonly rely on mash temperature as a means of adjusting dryness and sweetness. It’s well established that cooler mash temperatures favor beta amylase, an enzyme that creates a more fermentable wort and thus lower FG, while warmer temperatures favor alpha amylase, which results in less attenuation and a higher FG. The fact FG is a function of dextrin present in the fermented beer likely explains the widely accepted belief that it’s a good indicator of dryness.

Interestingly, out of the 5 mash temperature xBmts we’ve completed over the years, only 1 has returned significant results, though the beers in every trial were observed to have markedly different FGs. As a homebrewer of many years who was trained to use mash temperature as a means of adjusting sweetness, the consistency of these findings has been difficult for me swallow, so in the name of replication, I decided to test it out again on a style we’d yet to cover.

| PURPOSE |

To evaluate the differences between a German Pils mashed at 147°F/64°C and one mashed at 160°F/71°C.

| METHODS |

I went with my house German Pils recipe for this xBmt, as I feel it’s simple enough to display any differences caused by mash temperature.

Desert Summer

Recipe Details

| Batch Size | Boil Time | IBU | SRM | Est. OG | Est. FG | ABV |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5.5 gal | 30 min | 36.9 | 4.7 SRM | 1.049 | 1.007 | 5.51 % |

| Actuals | 1.049 | 1.007 | 5.51 % | |||

Fermentables

| Name | Amount | % |

|---|---|---|

| Odyssey Pilsner (Root Shoot Malting) | 6 lbs | 50.53 |

| Light Munich (Root Shoot Malting) | 5.25 lbs | 44.21 |

| Acidulated | 8 oz | 4.21 |

| Cara Ruby (Root Shoot Malting) | 2 oz | 1.05 |

Hops

| Name | Amount | Time | Use | Form | Alpha % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

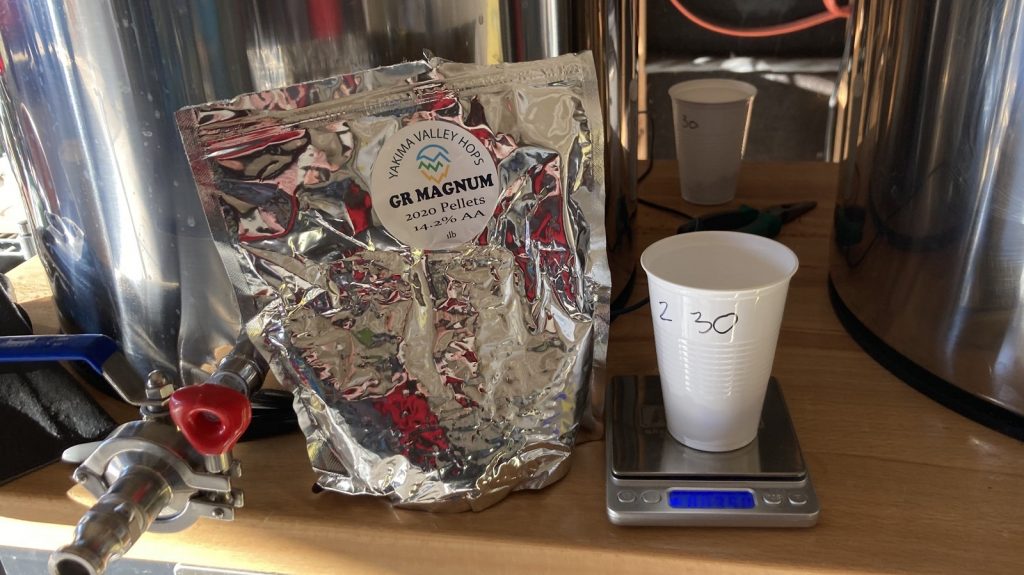

| Magnum | 28 g | 30 min | Boil | Pellet | 14.2 |

| Tettnang | 45 g | 5 min | Boil | Pellet | 4.5 |

Yeast

| Name | Lab | Attenuation | Temperature |

|---|---|---|---|

| Harvest (L17) | Imperial Yeast | 74% | 32°F - 32°F |

Notes

| Water Profile: Ca 61 | Mg 0 | Na 8 | SO4 75 | Cl 55 |

Download

| Download this recipe's BeerXML file |

I started my brew day by collecting identical volumes of RO water, adjusting each to the same profile, then flipping the switch on my controllers to get them heating up, after which I weighed out and milled the grain for each batch.

Once each batch of water was properly heated, I mashed in then checked to ensure both were at my target temperatures.

While waiting on the mash to finish, I prepared the kettle hop additions.

Once the mash step was complete, I collected the sweet wort in my kettle.

The wort was then boiled it for 30 minutes with hops added as stated in the recipe.

When each boil was finished, I quickly chilled the wort with my IC.

Refractometer readings showed the low mash temperature wort was 0.004 OG points lower than the beer mashed warmer.

I racked identical volumes of wort to sanitized fermenters then used my glycol unit to finish chilling them to my desired fermentation temperature of 50°F/10°C before pitching a single pouch of Imperial Yeast L17 Harvest into each.

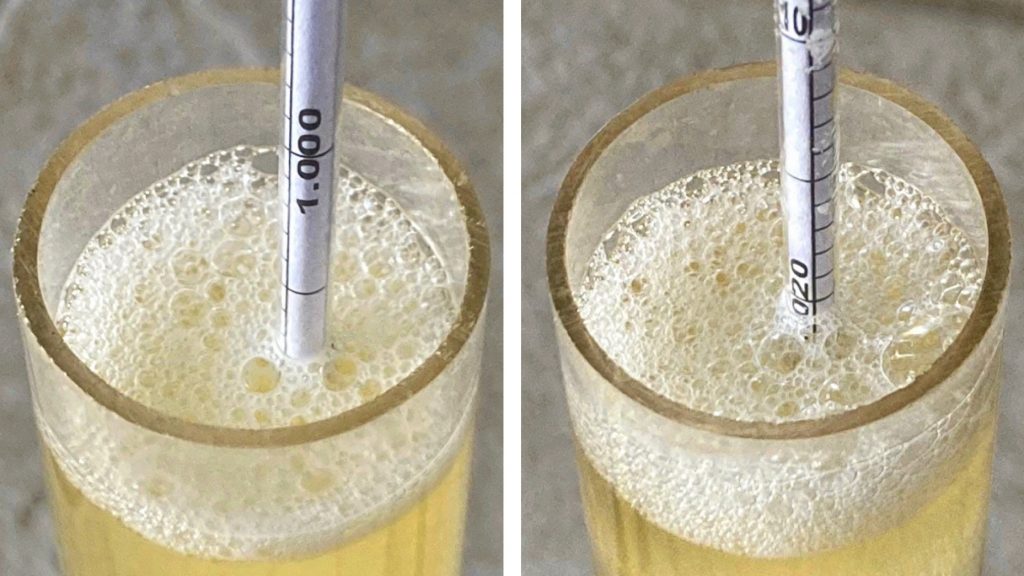

After 2 weeks, fermentation activity had dwindled in both beers so I took hydrometer measurements showing a rather drastic difference in FG.

I left the beers alone for 5 days before pressure transferring them to CO2 purged kegs.

The filled kegs were placed in my keezer and left to carbonate for a couple weeks before they were ready for evaluation.

| RESULTS |

Due to social distancing practices as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic, data for this xBmt was unable to be collected in our typical manner. As such, temporary adaptations were made involving the author completing multiple semi-blind triangle tests in as unbiased a way as possible.

Utilizing 4 opaque cups of the same color where 2 were inconspicuously marked, one set was filled with the low mash temperature beer while the other set was filled with the high mash temperature beer. For each triangle test, 3 of the 4 cups were indiscriminately selected, thus randomizing which beer was the unique sample for each trial. Following each attempt, I noted whether I was correct in identifying the unique sample. Out of the 10 semi-blind triangle tests I completed, I needed to identify the unique sample at least 7 times (p<0.05) in order to reach statistical significance. In the end, I correctly identified the unique sample just 5 times (p=0.21), indicating my inability to reliably distinguish a German Pils that was mashed at 147°F/64°C from one mashed at 160°F/71°C.

In sampling these beers side-by-side, I thought there was something different about them, though it was difficult to put to words. The fact I was only able to tell them apart in half of my triangle tests suggest they were far more similar than they were different, which isn’t a bad thing, as both were deliciously crisp, clean, and refreshing with a beautiful blend of graham cracker malt and subtle floral hop character.

| DISCUSSION |

Mash temperature is a variable that’s known to have an objectively measurable impact on beer due to the predictable enzymatic activity that occurs in certain environments. It’s likely this easily observable difference is what bolstered the widely accepted idea that mash temperature can also be used to modulate perceptible characteristics of beer, namely how sweet or dry it is. The fact I was unable to reliably distinguish a German Pils mashed at 147°F/64°C from one mashed at 160°F/71°C suggests any differences were minimal enough as to be imperceptible.

While these findings align with the majority of past xBmts on mash temperature, I found it rather striking that even the difference in OG between the beers wasn’t enough to make them easily distinguishable. Yet again, it would seem the measurable impact mash temperature has on FG and ABV may not necessarily lead be easily perceptible.

As weird as these results are to me, it really would seem that mash temperature is perhaps best used as a way to modulate alcohol level rather than sweetness. It’ll take a lot more experimentation to convince me it doesn’t have a perceptible impact at all, but based on the consistency of our findings, I’ll certainly be worrying less if I don’t hit my mash temperatures exactly on the nose in the future.

If you have any thoughts about this xBmt, please do not hesitate to share in the comments section below!

Support Brülosophy In Style!

All designs are available in various colors and sizes on Amazon!

Follow Brülosophy on:

FACEBOOK | TWITTER | INSTAGRAM

If you enjoy this stuff and feel compelled to support Brulosophy.com, please check out the Support page for details on how you can very easily do so. Thanks!

24 thoughts on “exBEERiment | Mash Temperature: Low vs. High In A German Pils”

Nice experiment with fascinating results. Talk to us more about this:

“While these findings align with the majority of past xBmts on mash temperature…snip…It’ll take a lot more experimentation to convince me…” Is this because you are thinking the experiments aren’t producing accurate results, or because the results are so counter to the conventional wisdom, or what? Not a criticism; I’m truly curious.

Change comes hard. I am curious too.

Very interesting Jake! My last three beers have been mash at 158F mainly to control FG from dropping below 1.010. I have not noticed any difference in the beers accept they are now finishing at the predicted FG instead of over attenuating. Without doing a side by side, the only thing I think I notice is they do not seems as thin as before.

Did you perceive any difference in the body or mouthfeel of the beers? Maybe after consuming a full pint vs a sample?

No way, I am sorry. I question the quality of the assessment. I would say most can tell the difference in a 1.007 beer and a 1.022 beer.

That’s gotta be a typo?! maybe 1.012 look at the hydrometer in the picture.

The hydrometer reading on the right is definitely greater than 1.020. The left is clearly between 1.010 and 1.000. Remember, the further down the hydrometer, the higher the gravity.

I stand corrected on the hydrometer… but i still find it very hard to believe you can’t taste the difference between 1.007 and 1.021. in some cases this is the difference between a style.

Why? Care to elaborate on your reasoning? Which part of the 4 assessments do you question? It seems like a convincing weight of reasonably well controlled data pointing to the fact it does not make a big difference. Versus?

Well this certainly lends credence to my observations that I can’t detect differences in FG of 2-4 points for beers in typical gravity ranges. I’ve stopped taking FG reading years ago because of this and I only do it now when I’m troubleshooting a beer that didn’t come out as expected, or if testing a new process change.

I’m surprised to see such a huge difference in FG between the two beers. I’ve mashed as high as 162F without seeing more than a few points difference in FG. How long did you mash for?

I’m slowly going that route as well. I now have settled on about 5 beers that I brew on a regular basis and if one comes out way off target, I brew it again and check everything.

Has there been any discussion within Brulosophy about the statistical power of a triangle test with only 10 trials? It doesn’t seem to me like that is enough data to drive as strong a conclusion as is stated here. Has there been any discussion of adopting a different test method?

Bravo!!! Another exBEERriment in relation to a old post of Bierstadt, is brewing the same recipe but but two very different German hops (example: Magnum vs Hallertauer Mittelfrueh). https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=PDgBj1KGOdc&t=5934s

Interesting that you get the same result on almost every single Xbmt.

A few years ago I did the Siebel off-flavor kit with my homebrew club and was fascinated by how different everyone’s perceptions of aroma and flavor were. There were some flavors I couldn’t detect but others could smell from a foot away. On other flavors, it was the opposite. When I had Covid last month and lost taste and smell and they slowly but not linearly returned, I was again amazed at how our perceptions can change when they become uncalibrated. I’m wondering, is the variable here your single taste tester instead of your usual group? Maybe this is an area where the author can’t detect the gravity difference but other (maybe a statistically significant number of) brewers could?

We’ve done multiple mash temp xBmts when Covid wasn’t an issue and data was collected from actual tasters:

https://brulosophy.com/2015/10/12/the-mash-high-vs-low-temperature-exbeeriment-results/

https://brulosophy.com/2016/08/22/the-mash-pt-2-testing-a-less-extreme-temperature-variance-exbeeriment-results/

https://brulosophy.com/2018/08/13/mash-temperature-147f-64c-vs-164-73c-exbeeriment-results/

https://brulosophy.com/2020/01/13/mash-temperature-low-vs-high-in-a-high-og-belgian-ale-exbeeriment-results/

How about dropping the ubiquitous COVID excuse, and just invite your friends over? If they are paranoid, have them sit 8 feet apart, double masked.

And, you are able to differentiate the two beers 50% of the time. That is a meaningful stat.

He correctly picked the odd-beer-out 50% of the time, but that doesn’t mean he was differentiating them half the time. Failure to hit their pre-determined threshold for meaningfulness (p<0.05) means they can't conclude that picking the correct beer 5 times instead of just 3.3 times was anything more than chance.

A mash at a lower temperature is slower – what were the mash times? I mash at low temperature, and just go do errands.

Isn’t the Munich malt kilned at a higher temp which makes much less susceptible to mash temp variation ? Run the experiment again and cut the Munich down to 10%. And I agree, these experiments lose most of their meaning when only one person is sampling.

Interesting. Mouthfeel, and body are the main reason why I typically mash higher, with my czech pilsner. A beer with the same alcohol content, low mash temp (low finally gravity beers), usually feel thin to my pallet. Of course this means that I have to use a lot more grain than the a average brewer.

Nice experiment…..as usual. Everything you do is interesting! However, what statistical test do you actually use to generate the p value? I’ve spent my working life in lab science and I find had to see that your experimental design can have such statistical power!

Be interest to know….

Cheers

If we accept these findings, how then do we adjust sweetness/dryness of a particular recipe? I’m getting ready to brew a Scotch Ale and would like it to be on the dry side.

That’s a lot of Munich for a pils

I’ve been trying to increase the sweetness in an Imperial Black IPA with a massive amount of boil hops. It’s a clone of a retired beer and the recipe came from the head brewer. Theirs had very assertive and defined bitterness and definite sweetness balancing it, So far using Mash Temp to obtain more sweetness has pretty well failed. Ironically the brewer who gave me the recipe suggested a higher mash temp to bring out more sweetness, so that must have been their approach that worked. But it hasn’t for me. I wonder if scale could be impacting these results in any way, Nothing comes to mind, but its interesting to consider