Author: Phil Rusher

Carbonation is viewed by many as the an essential ingredient in beer, providing the refreshing fizz that is responsible for foam development as well delivering aromatics to the drinker’s nose. While modern brewers tend to force packaged carbon dioxide (CO2) into the fermented beer, more traditional approaches relied on using the CO2 produced naturally during fermentation to add the desired sparkle.

Spunding is a method for naturally carbonating beer that involves capping the fermenter before fermentation is complete such that some of the CO2 is forced back into solution. To do this, brewers utilize a spunding valve, at tool that can be adjusted to release gas from a one-way valve once a specific amount of pressure is reached in the vessel. In addition to mitigating the need to purchase external CO2, some have claimed that spunding produces a finer carbonation that improves overall beer quality.

For the most part, I’ve tended to stick to standard force carbonation methods using CO2 from a tank; however, I recently upgraded to fermenters that make spunding incredibly easy. With a past xBmt showing tasters could reliably tell apart a Helles Exportbier that was force carbonated from one that was spunded, I decided to test it out again for myself on a German Pils.

| PURPOSE |

To evaluate the differences between a German Pils carbonated using either force carbonation or the spunding method.

| METHODS |

I went with a simple German Pils recipe for this xBmt because, in addition to being a style that was traditionally spunded, it’s clean enough to allow any impact of carbonation method to show.

Polarstern

Recipe Details

| Batch Size | Boil Time | IBU | SRM | Est. OG | Est. FG | ABV |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5.5 gal | 90 min | 40 | 3.7 SRM | 1.049 | 1.007 | 5.51 % |

| Actuals | 1.049 | 1.007 | 5.51 % | |||

Fermentables

| Name | Amount | % |

|---|---|---|

| Gateway: Under-modified Barley Wind-Malt | 10.5 lbs | 88.42 |

| Vanora: Vienna-style Barley Malt | 1.375 lbs | 11.58 |

Hops

| Name | Amount | Time | Use | Form | Alpha % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Magnum | 14 g | 90 min | Boil | Pellet | 12 |

| Perle | 17 g | 15 min | Boil | Pellet | 6.7 |

| Perle | 22 g | 5 min | Boil | Pellet | 6.7 |

Yeast

| Name | Lab | Attenuation | Temperature |

|---|---|---|---|

| Urkel (L28) | Imperial Yeast | 75% | 32°F - 32°F |

Notes

| Water Profile: Ca 86 | Mg 0 | Na 36 | Cl 93 | SO4 125 |

Download

| Download this recipe's BeerXML file |

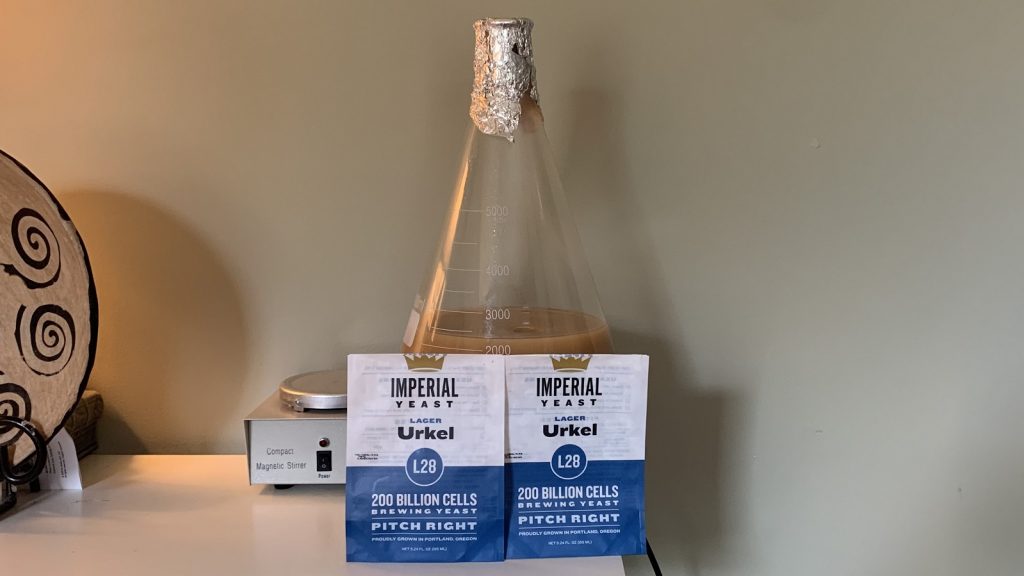

A few days before brewing, I made a starter with 2 pouches of Imperial Yeast L28 Urkel.

On brew day, I collected the water for a single 10 gallon batch and adjusted it to my desired profile before preparing the grain.

Given the use of under-modified base malt, I opted for a traditional step mash for this batch, allowing the mash to rest for 20 minutes at 3 different temperatures.

When the mash rest was complete, I separated the grain from the liquid and then weighed out the kettle hops while the wort was heating up.

The wort was boiled for 60 minutes with hops added at the times listed in the recipe.

Once the boil was finished, I quickly chilled it with my IC.

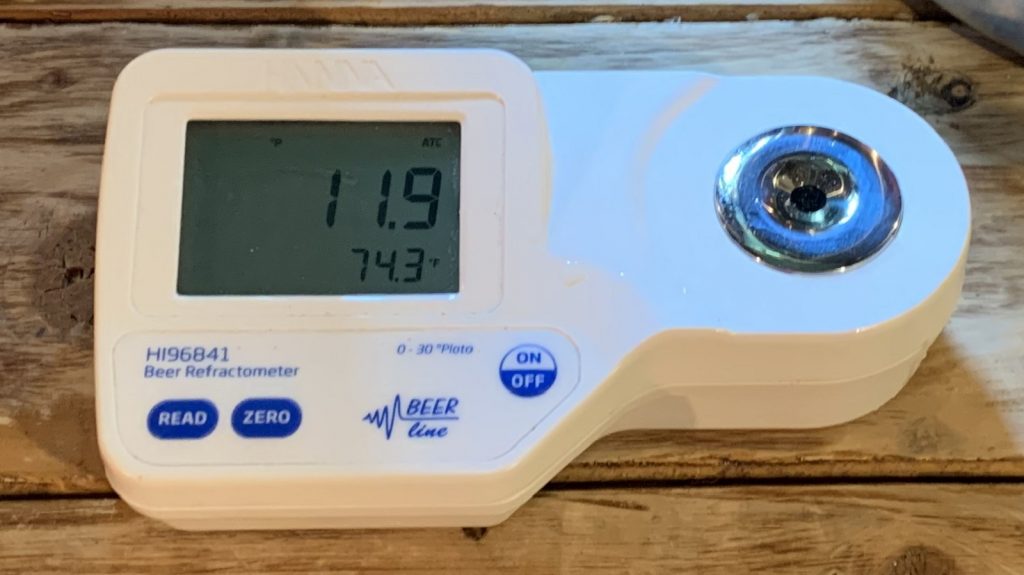

A refractometer reading showed the wort was at my expected OG.

Identical volumes of wort were pumped to separate fermenters where my glycol rig was used to finish chilling them to my desired pitching temperature of 54°F/12°C, at which point I evenly split the yeast starter between each batch and set the controller to maintain a fermentation temperature of 63°F/17°C.

After 3 days of fermentation, I raised the temperature of both beers to 68°F/20°C and attached a spunding valve set to 29 psi to one of the fermenters.

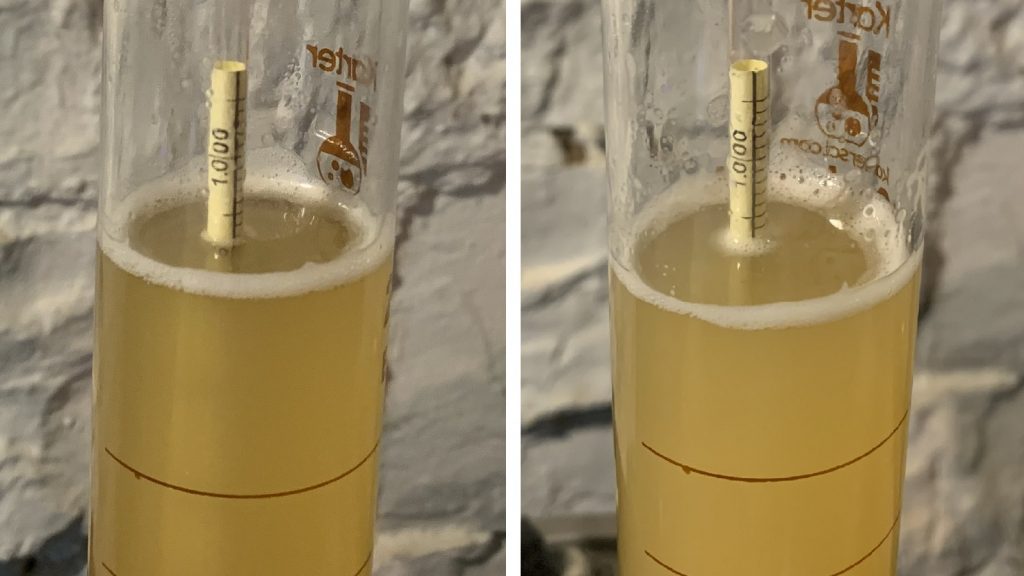

The beers were left alone for another week before I took hydrometer measurements showing both reached the same FG. At this point I cold crashed the beers and let them sit in the tanks for another 2 weeks.

I proceeded with pressure transferring the beers to CO2 purged kegs.

The filled kegs were placed in my keezer and left alone for 2 weeks before they were ready for evaluation.

| RESULTS |

Due to social distancing practices as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic, data for this xBmt was unable to be collected in our typical manner. As such, temporary adaptations were made involving the author completing multiple semi-blind triangle tests in as unbiased a way as possible.

Utilizing 4 opaque cups of the same color where 2 were inconspicuously marked, one set was filled with the force carbonated beer while the other set was filled with the beer carbonated using the spunding method. For each triangle test, 3 of the 4 cups were indiscriminately selected, thus randomizing which beer was the unique sample for each trial. Following each attempt, I noted whether I was correct in identifying the unique sample. Out of the 10 semi-blind triangle tests I completed, I needed to identify the unique sample at least 7 times (p<0.05) in order to reach statistical significance. In the end, I correctly identified the unique sample 4 times (p=0.44), indicating my inability to reliably distinguish a German Pils that was force carbonated from one that was carbonated using the spunding method.

These beers were perceptibly identical to my palate, both being crisp and bright with nice hop flavor, which is exactly what I look for in German Pils. In addition to noticing no differences in aroma, flavor, or mouthfeel, carbonation level and foam quality were the same as well.

| DISCUSSION |

Spunding is a strategy brewers can utilize to carbonate their beer that involves capping the fermenter prior to the completion of fermentation such that naturally produced CO2 is forced into solution. While some believe this method has a similar impact as force carbonation, others contend it results in a beer with finer carbonation and better head retention. The fact I was unable to reliably distinguish a German Pils that was force carbonated from one that was carbonated using the spunding method suggests any differences were minimal enough as to be imperceptible.

Seeing as tasters in a past xBmt were able to tell apart a German Helles Exportbier that was force carbonated from one that was spunded, I expected the same from this xBmt, but that wasn’t the case. In considering explanations for these findings, it seems possible the more subtle quality of Helles Exportbier may have allowed subtle differences to shine compared to the somewhat more assertively hoppy German Pils I brewed. Still, these beers were very clean with a noticeably present malt character, so it’s possible the different carbonation methods simply contributed similar characteristics to the beers.

Spunding requires additional gear and a couple extra steps, but it can be a boon to brewers looking to naturally carbonate their beer while minimizing cold-side oxygen exposure, plus it also reduces the need for external CO2. These are all positives in my book, and the fact I couldn’t tell the beers in this xBmt apart has motivated me to continue using the spunding method to carbonate most of my beers.

If you have any thoughts about this xBmt, please do not hesitate to share in the comments section below!

Support Brülosophy In Style!

All designs are available in various colors and sizes on Amazon!

Follow Brülosophy on:

FACEBOOK | TWITTER | INSTAGRAM

If you enjoy this stuff and feel compelled to support Brulosophy.com, please check out the Support page for details on how you can very easily do so. Thanks!

26 thoughts on “exBEERiment | Carbonation Methods: Force Carbonation vs. Spunding In A German Pils”

I’ve never spund carbonated as most of my beers are IPAs with huge post-ferm dry hops (think explosion), but I’ve often wondered if I tried on other styles do you get excessive foaming when transferring to the keg when cold (i.e. foam coming out of gas post or PRV when near full)? I suppose you could try positive pressure with another spunding attachment on the keg out post but it’s a bit elaborate. How did you find the process?

I also brew mostly ipa’s and dry hop post fermentation. I’ve learned to ferment, dry hop and transfer to the keg all under a constant 8psi, keeping the co2 in the beer. No foaming issues at all.

Is this dry hopping with spunding? what sort of dry hop charge are you talking about? I typically dry hop around 16g/l and I’m concerned throwing this in a fully carbed beer would create a geezer..

I transfer from a unitank under pressure to kegs the same as you but carb after to avoid any of the above…

I have a spool that sits between a butterfly valve on the top of my Spike CF-5 and a Blichmann spunding valve. The blow off runs through this set up during fermentation. The spool holds about 4 oz. of pellet hops. To dry hop, I close the butterfly valve, release the pressure in the spool and remove the spunding valve. I then fill the spool with the dry hop charge, purge the spool with co2, seal all clamps and open the butterfly valve to drop the hops. If the recipe calls for additional hops, I simply repeat the process.

I use basically the same system as yours to dry hop – spool, butterfly valve, gas post, the lot. My spool probably takes around 25oz of hops which I typically fill for a 14gal batch (and sometimes more ). I know the more you add the more nucleation sites for CO2 release which is why it’s not so much an issue for small additions. Its all sealed like yours but I’ve seen some fantastic videos of sealed unitanks blowing open ports after too much hops added to a carb’d beer all at once. The solution I guess is to add smaller charges and make sure the pressure doesn’t rocket before adding more. This is what I’ve read to do on some professional sites when dry hopping but wasn’t sure at what level it can become an issue. Knowing 4oz (in 20ish litres??) is safe is a good starting point I guess

25 oz… that’s a big spool! Mine is 8″ tall (1.5″ TC) and holds only 4 oz.

Right, nucleation can be a deadly serious topic for brewers! Especially the poor unfortunate souls who create dry hop geysers…

For me, I have some positive pressure on the unitanks and use small diameter tubing, both for the transfer of beer into the keg and the displacement of CO2 from the keg into the bucket of sanitizer. This creates a pretty gentle process that I’ve had no issues with, other than taking a bit longer. Meh.

Nothing elaborate about the transfer process on a spunded beer, at least for me. I ferment in a keg, so I just move the spunding valve from my fermentation keg to the serving keg and jump the beer over under a bit of CO2 pressure. As long as you go slow and the pressure gradient betwen the two kegs is small, then there isn’t much foaming to speak of.

If I’m not running a pressurized fermentation, then I use my spunding valve as a PRV valve initially and leave it between 2 and 5 PSI for the first few days of fermentation. When I dry hop, this isn’t enough carbonation to cause a gusher. I clamp down my spunding valve after the hops go in. There usually isn’t enough extract left at this point to fully carbonate the beer, but I at least have a partially carbonated beer to transfer.

Which beer is which in the final picture? The heads look a little different.

The force carbonation beer is on the left and the spunded beer is on the right. The *very* slight difference in foam is just timing related. I poured the spunded beer before the other one, then had to run upstairs to get a picture in my kitchen because the lighting is better there than in my basement!

It would be interesting to age these beers for a couple of months then taste for a difference again. Some have said that the small levels of O2 from a CO2 tank will eventually oxidize the beer, while the spunded beer should stay fresher longer having no O2 pickup from the carbonation process.

The 0.01% contaminants in beverage gas probably doesn’t include O2. It’s usually hydrocarbons, nitrogen and sulphur containing compounds as these are chemicals that must be filtered out during the purification process. Some (but certainly not all) are also created during fermentation and would be present in a spunded beer. If there were any measurable O2 it certainly would be less than the amount of O2 pickup from things like keg and disconnect O-rings and diffusion through permeable tubing which all let ppm levels of O2 in over a space of a few weeks.

I’d wager any difference in spunded vs non spunded beer would be equally attributable to fermentation pressure which has a known effect on yeast activity (even if hard to detect in recent experiments)

Agree with contaminants comment. I’d also add that in an environment where the kegs are fully closed and there is no possibility for additional exposure to the environment, any negative/oxidative effects in packaged beer would show up rather quickly. That said, I agree that it will be interesting to see how (if?) these beers differ after a period of keg conditioning.

My hunch is that it’s really difficult to replicate the kind of pressure that affects fermentation on the homebrew scale.

I have a couple of questions. Did the carbonation of the spunded sample not effect the FG reading? I’ve read that you should filter the sample through a coffee paper to remove the carbonation to take an accurate reading, or is this nonsense?

Second question – Why did you wait three days after fermention had started and why did you set the valve to 29PSI? Did you use some kind of calculator? I know that 29PSI at 20C gives you roughly 2.5 volumes of C02 but is that the same during active fermentation?

Question 3 – Were you not worried that fermenting under pressure would alter the beer character?

Definitely not nonsense! I’ve done the coffee filter thing but usually just I let the samples degas a bit by letting them sit and warm up for a few minutes and doing some light shaking/stirring afterward. I also spun the hydrometer to discourage bubbles from adhering to it. It’s possible that the reading was affected by the gas, but I do not think it’s likely. It’s probably safe to say that even if it is affected, it’s marginal.

I waited three days to pressurize the vessel because that’s when the beer was nearly done fermenting; a gravity reading from then was about 1.016. According to the standard carbonation charts that we all use, in order to get 2.4 – 2.5 vol of CO2 at 68F/20C I’d need to have a pressure of about 29-30 PSI, so I wanted to ensure that there were enough fermentables left in solution to contribute that.

I wouldn’t quite qualify this as fermenting under pressure because it was only pressurized for the last 0.009 SG points. But this difference is one of the things we were interested in testing.

So is the idea that once the beer is chilled it would be at a regular carbonation level? Like 12 PSI but carbonated?

More or less, yes. I let the beers cold crash for 2 weeks, making sure that the force carbonation beer maintained 10-12 PSI while not introducing any additional CO2 to the unitank containing the spunded beer. At the time that the beers were kegged the pressure gauge for the spunded beer read about 15 PSI, but both of the beers were transferred to kegs at only 2-3 PSI with the valves used for racking only opened partially.

Interesting experiment Phil… And German Pils is one of my favorite and most brewed beers.

Question I have is actually about the malt. How do you like Gateway (under modified malt), and how do you think it compares to the other malts available for Pilsners. You added a protein mash, like I would for Weyermann Bohemian floor malt (20 min rest at 120-something Fahrenheit)?

Perhaps this would make a good separate exbeeriment, but I was interested in this malt and wanted to get some feedback from a person that has used it.

This was actually my first time using Gateway for the base malt of a lager. It was interesting and it gave it a very rustic, one might even say farmhouse flavor profile. I think I’ll dial back the proportions when using Gateway for future lager beers. It’s got this grainy sweetness that works really, really well in things like Belgian styles, but I tend to look for more traditional crackery type flavors in pilsner.

I’d recommend doing a protein rest for any under modified malt, unless that’s the flavor profile you’re looking for.

We did a protein rest xbmt before and I’m planning on doing another one with under modified malt!

Thanks for the info.

On the previous iteration of this variable, Jake noted that he lagered the beer for 60 days before serving to tasters. He also noted that his own impression was that the two beers were basically indistinguishable soon after kegging, but that he could consistently distinguish the the odd-beer-out after the lagering period. Perhaps the lack of age in this experiment is the reason for the inability to distinguish the beers?

Or conversely, perhaps Jake had something weird about one of his kegs (a stray contaminant that managed to hide from the sanitizer?) that just took time to impact the beer?

This was on my mind too. I had been wondering about what sort of flavors in Jake’s beer may have been derived from spunding in the keg due to all the yeast that’s generated. This was essentially a non-issue for me since I had dumped the yeast and purged the racking arm in the unitank. I am looking forward to seeing what it tastes like in a few weeks!

In the previous experiment (p>0.05) cited in paragraph three a German yeast (Augustiner) was used and in your experiment (p<0.05) a Czech (Pilsner Urquel) strain was used. Could this be the difference? That some strains respond and others are unaffected?

It’d be a bit of a stretch to single out the yeast strain as being the culprit that made this xBmt non-significant given that every other ingredient, and even the water profile and fermentation vessels/process, were different from the original xBmt. I think it’s more likely that these beers made under these conditions were simply not very different from one another. That said, I do think it would be interesting to do another trial that is more in line with traditional German ingredients and processes n

Thanks for the experiment. I do wonder why you raise the temperature and cold crash it later on. I use the spunding technique on all my Lagers, but instead of raising, I slowly (0.5 Celsius a day) reduce the temperature from 10 to 6 Celsius, at the same time spunding at 15 psi. After fermentation is completed I further reduce to 1 Celsius (after removing the yeast/transfer to kegs) and store for 60 days at the same low temperature. Perhaps you could perform a comparison with this fermenting profile?

I usually approach things from the perspective of “what needs to happen for this fermentation” or “how can I make the yeast happy to do their job?” Generally speaking, most brewer’s yeast will start to have sluggish activity when under pressure, so because I wanted to promote an environment that would be more conducive to yielding a fully attenuated beer, I made sure to encourage fermentation by increasing the temperature along with the pressure.

I’m not familiar with the fermentation schedule you’re proposing, and it seems counter productive to me since decreasing the temperature, gradual as it is, will discourage yeast activity. I’d be less inclined to do this for strains that are well known producers of diacetyl and sulfides.