Author: Jake Huolihan

Of the less common ingredients used to make beer throughout the course of history, honey is certainly one of the more popular, with brewers adding the highly fermentable sweet nectar to a range of styles to boost both flavor and alcohol levels. While honey can be used at various points in the brew process, many prefer adding it during fermentation, as it’s believed the heat of the boil will drive off desirable characteristics.

A major concern in brewing is contamination, which is most likely to occur when certain microbes are introduced to the beer on the cold-side. When making honey additions during fermentation, it makes sense that a brewer might be concerned about contamination, hence some choose the less risky route of pasteurizing the honey with heat before putting it in their beer.

Similar to the arguments against adding honey to boiling wort, critics not only contend that pasteurization results in the loss of volatile flavors, but that it’s largely unnecessary because of the antibacterial nature of honey. As someone who loves honey in general and appreciates what it contributes to certain styles of beer, I’ve wondered about the necessity of pasteurization and decided to test it out for myself.

| PURPOSE |

To evaluate the differences between a Helles Bock dosed with raw honey during fermentation and one where the honey was pasteurized before being added.

| METHODS |

One of my favorite Wisconsin beers that I can’t get in Colorado is New Glarus’ Cabin Fever, a delicious Helles Bock. While recipe details are scant, I used it as inspiration for this xBmt recipe, relying on the addition of honey to bump the strength into to Bock territory.

Business End

Recipe Details

| Batch Size | Boil Time | IBU | SRM | Est. OG | Est. FG | ABV |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5.2 gal | 30 min | 43.2 | 5.1 SRM | 1.067 | 1.011 | 7.35 % |

| Actuals | 1.067 | 1.011 | 7.35 % | |||

Fermentables

| Name | Amount | % |

|---|---|---|

| Odyssey Pilsner | 12.25 lbs | 81.67 |

| Honey | 2.25 lbs | 15 |

| Carahell (Weyermann) | 4 oz | 1.67 |

| Melanoidin (Weyermann) | 4 oz | 1.67 |

Hops

| Name | Amount | Time | Use | Form | Alpha % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Loral | 30 g | 30 min | Boil | Pellet | 11.5 |

| Tettnang | 30 g | 15 min | Boil | Pellet | 4.5 |

Yeast

| Name | Lab | Attenuation | Temperature |

|---|---|---|---|

| Harvest (L17) | Imperial Yeast | 72% | 32°F - 32°F |

Notes

| Water Profile: Ca 61 | Mg 0 | Na 8 | SO4 75 | Cl 55 |

Download

| Download this recipe's BeerXML file |

I started this brew day by collecting RO water, adjusting it to my desired profile, then flipping the switch on my controller to get it heating up before weighing out and milling the grain.

With the water properly heated, I mashed in then checked to ensure it was at my target temperature.

I let the mash rest for 60 minutes, returning every 15 minutes to give it a stir.

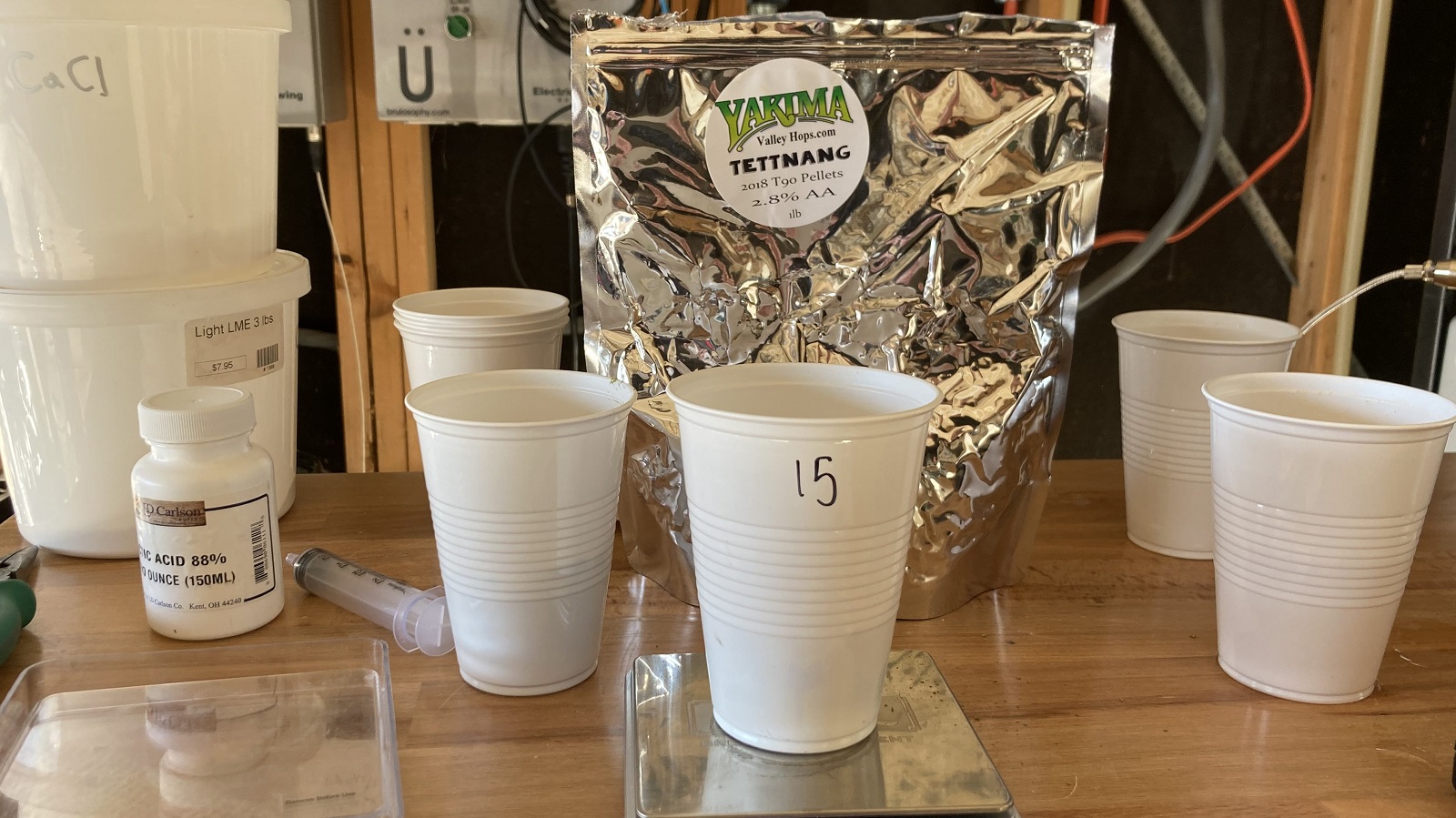

While waiting on the mash to finish, I prepared the kettle hop additions.

Once the mash step was complete, I collected the sweet wort in my kettle and boiled it for an hour, adding hops at the times listed in the recipe.

Following the 60 minute boil, I quickly chilled the wort with my IC.

A refractometer reading showed the wort was at my target pre-honey OG.

After evenly splitting the wort between two fermentation vessels, I used glycol to quickly finish chilling them to my desired fermentation temperature of 50°F/10°C before pitching a single pouch of Imperial Yeast L17 Harvest into each.

After 9 days of fermentation, I added 2.25 lbs/1,020 g of raw honey directly to one of the beers while the honey for second batch was first held at a pasteurization temperature of 150°F/66°C for 30 minutes.

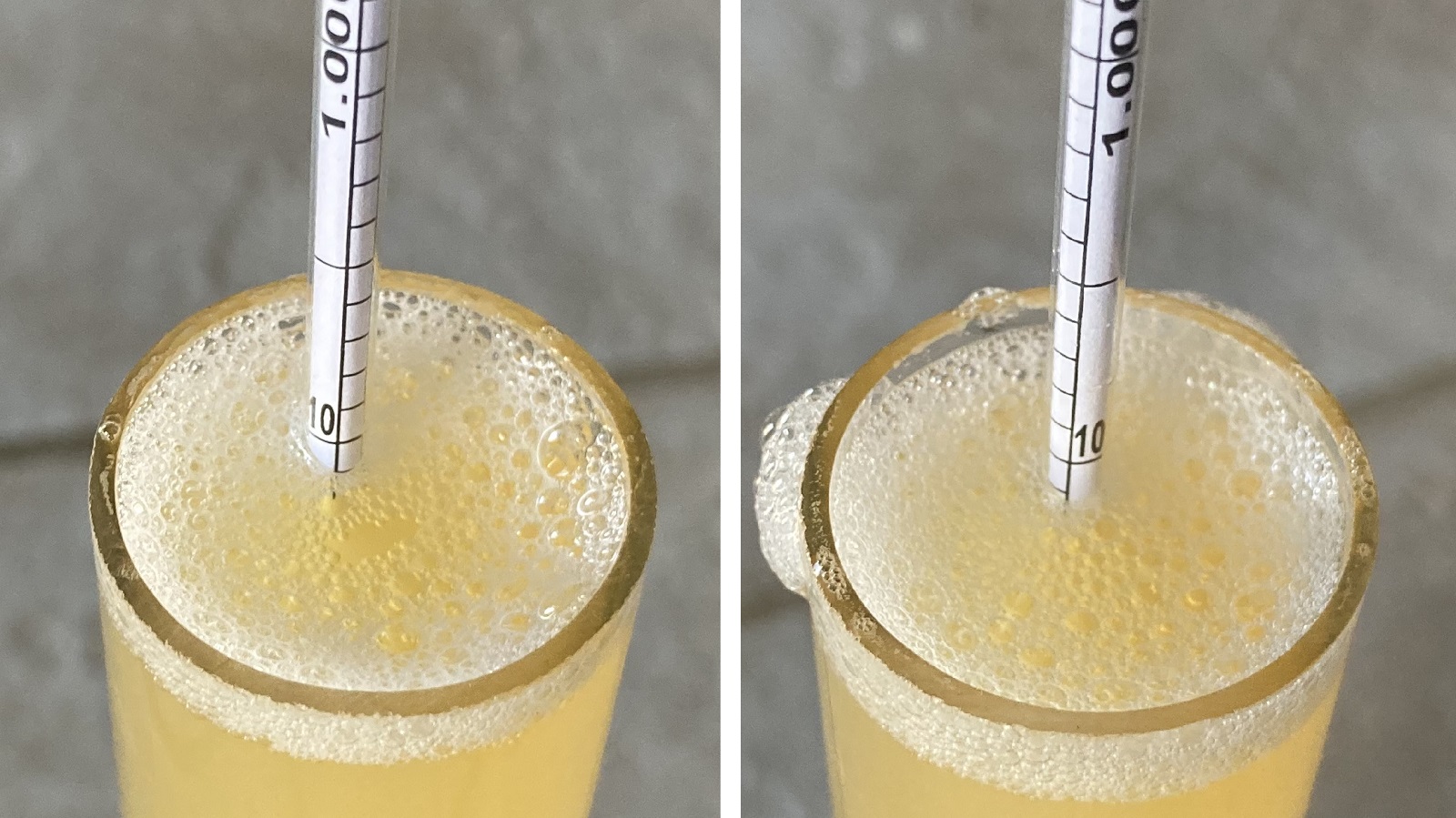

The beers were left to ferment the honey for an additional 11 days before I took hydrometer measurements indicating both reached the same FG.

At this point, I racked the beers to CO2 purged kegs that were placed in my keezer and left to carbonate for a couple weeks before they were ready for evaluation.

| RESULTS |

Due to social distancing practices as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic, data for this xBmt was unable to be collected in our typical manner. As such, temporary adaptations were made involving the author completing multiple semi-blind triangle tests in as unbiased a way as possible.

Utilizing 4 opaque cups of the same color where 2 were inconspicuously marked, one set was filled with the beer made with raw honey while the other set was filled with the beer made with pasteurized honey. For each triangle test, 3 of the 4 cups were indiscriminately selected, thus randomizing which beer was the unique sample for each trial. Following each attempt, I noted whether I was correct in identifying the unique sample. Out of the 10 semi-blind triangle tests I completed, I needed to identify the unique sample at least 7 times (p<0.05) in order to reach statistical significance. In the end, I correctly identified the unique sample just 2 times (p=0.90), indicating my inability to reliably distinguish a Helles Bock where raw honey was added during fermentation from one where the honey was first pasteurized before being added to the beer.

There was absolutely nothing about these beers that I perceived as being different, they tasted identical every time I sampled them. I felt both were delicious, the honey adding a nice depth of flavor, almost a bit too good to have on tap during quarantine considering how strong it was.

| DISCUSSION |

With its sweet floral and earthy flavors, honey can make an excellent addition to a wide range of styles, from easy-drinking pale lager to monstrous Imperial Stout. While it’s been claimed that treating honey with heat drives off desirable volatile compounds, my inability to distinguish a Helles Bock made with raw honey from one made with pasteurized honey suggests both beers possessed similar enough characteristics as to be indistinguishable.

On the other side of the token, my inability to distinguish these beers also suggests the raw honey did not lead to a contamination, which supports the idea held by many that pasteurization is largely unnecessary due to honey possessing natural antibacterial qualities. Of course, honey only contributed 15% of the fermentables in these beers, whereas much of the talk about how to treat it comes from the mead-making world, so it’s certainly possible results would be different when using larger amounts.

Considering the anecdotal reports of many alongside my own experience in this xBmt, I’m personally compelled to believe that pasteurization doesn’t greatly hinder honey character, though given its natural antibacterial nature, it’s also not a necessary step. Going forward, I’ll continue using what I believe to be the easiest approach, which is dumping the honey straight from the container without pasteurizing it.

If you have any thoughts about this xBmt, please do not hesitate to share in the comments section below!

Support Brülosophy In Style!

All designs are available in various colors and sizes on Amazon!

Follow Brülosophy on:

FACEBOOK | TWITTER | INSTAGRAM

If you enjoy this stuff and feel compelled to support Brulosophy.com, please check out the Support page for details on how you can very easily do so. Thanks!

7 thoughts on “exBEERiment | Impact Pasteurization Of Honey Has On The Character Of Pale Lager”

I think the risk of contamination during fermentation is way overstated, as long as an airlock is used on an airtight fermenting vessel, and normal, basic, cleaning standards are followed. I make wine from raw, garden fruit with the wild yeasts still on the skins and no doubt various wild bacteria present. There are yeasts and various wild bacteria on barley as well. I make sourdough yeast from them by just adding water to the raw barley flour and allowing a fermentation to start naturally; then use that to ferment my fruit and beer. I’ve never had any problems with contamination during fermentation, except once or twice before I started using an airlock on an air-tight fermentation bucket. That was due to acetic acid bacteria turning the the alcohol into vinegar. Nothing particularly poisonous or dangerous about acetic bacteria either. They are used to make all vinegar, including the fashionable apple cider vinegar and in making sourdough bread. I just don’t like the flavor in beer or wine! Cut out the air getting to the fermenting wine and it is no longer a problem. I certainly don’t sterilize fruit before fermenting. Any bacteria in natural honey are likely to be fairly innocuous aerobic bacteria which cannot survive without a supply of air. I was aghast that some people add sodium metabisulfite to honey before making mead. The carbon dioxide suffocates most bacteria while the yeast can thrive. In beer-making we normally boil the beer before fermentation, thinking it is necessary to kill any bacteria, as well as obtain the bittering and flavoring effect of the hops. However, no boiling is done in wine fermentation so it can’t be essential. In the old days, boiling the water was important (they didn’t know at the time), when the water was contaminated with various disease causing bacteria, many of them dangerous anaerobic bacteria. Thankfully, mains supplied tap water is now free of those kinds of dangerous bacteria, I have made beer without boiling the wort after the mash. The hops were added to the mash container and also as dry hopping after fermentation..Fermentation was straight after mashing and sparging. No contamination issues at all. However, the beer was very lacking in bitterness for my taste. I had to add concentrated hop extract to the finished beer in the end.

If you really want to know if there is any contamination make an ale, not lager.

A lot of MO do not develop at 10 C

I once talked to a beekeeper who also brews (or a brewer who also keeps bees :-)), and he added his honey at ten minutes before the end of the boil. Mind you, this person brewed commercially, so he chose this way to adhere to safety standards. But I suppose that he was more or less happy with the result, otherwise he wouldn’t do it any more.

The comments that are disregarding honey as a potential contaminant are just verifiably wrong. Honey only has its preservative qualities when it is in its undiluted form. Honey is bacteriostatic, not bactericidal.

It’s all well and good that some people have favorable anecdotal experiences, but that runs completely counter to the scientific method, and the scientific data on the subject.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6589292/

That, and clostridium botulinum is also known to contaminate it. Fortunately beer should be too acidic for it to grow, but it can contain many different organisms. It’s bee puke.

Some wine makers use the natural yeast on the skins of their grapes to make wine. Sometimes that works, sometimes not so much.

We live in a soup of micro-organisms, it’s a gamble who wins whenever we brew but there are ways to try and keep the odds in our favor.

The conclusion of the article you’ve linked begins, “the antibacterial effects of honey have been shown to be quite potent.”

see https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6589292/#sec2.7

I’m curious if there was a difference after the original beer created in the article aged for a few weeks or more. Considering the tasting notes, I would be agape to find that it lasted more than a week. I don’t drink much, so my brews occasionally sit on the shelf for several months to several years before being consumed (sometimes this is intentional) and it’s really fun to read the tasting notes when fresh vs. tasting a well aged grand cru or imperial helles bock.