Author: Cade Jobe

Despite current preferences trending toward hazy IPA, many drinkers still prefer the refreshing qualities of a nice pale lager, which are known for their brilliant clarity. Traditionally, lager styles are fermented cool with bottom-fermenting yeast strains then stored at temperatures near freezing over an extended period of time, during which particulates drop out and the beer achieves its characteristic clarity. Indeed, time is proven to be a good clarifier of beer, but for those who prefer to hasten the process, there are chemical solutions.

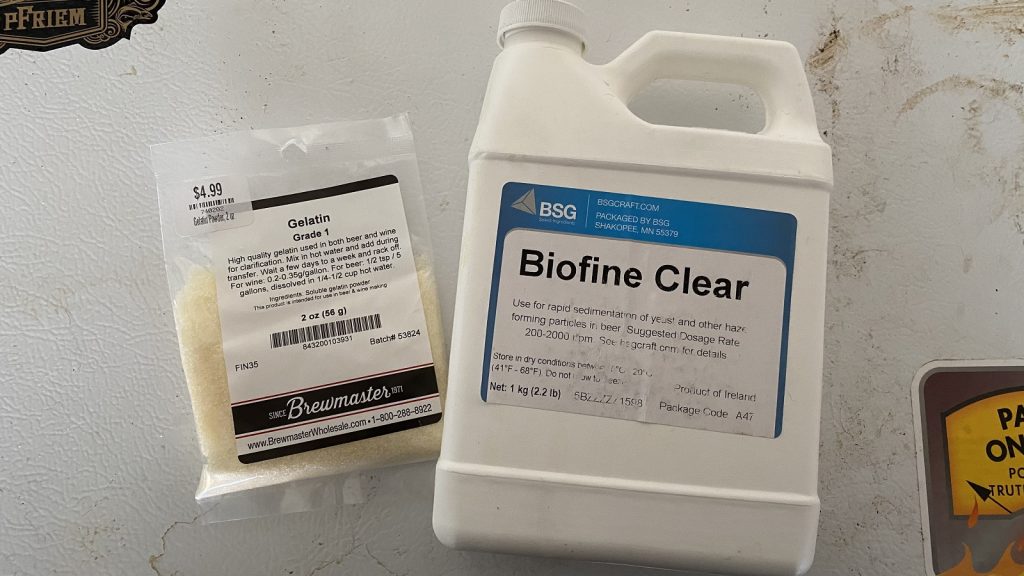

One fining agent that has proven very effective at clearing beer is gelatin, which becomes positively charged when mixed with water, thus attracting negatively charged particles to the point they become heavy enough to drop out of solution. A common argument against the use of gelatin is that it’s an animal product, meaning it renders beer undrinkable by vegetarians and vegans. For this reason, many commercial brewers have begun using a fining agent called Biofine Clear, which is a purified colloidal solution of silicic acid that encourages sedimentation of yeast and other haze forming particles.

I’ve had positive experiences using both gelatin and Biofine Clear in my brewing, with neither leading to the reduction in flavor some seem to believe is guaranteed when fining beer. With a past xBmt showing tasters could not reliably tell apart a Kölsch fined with gelatin from one fined with Biofine Clear, I decided to test it out again in a delicate American Light Lager to see for myself.

| PURPOSE |

To evaluate the differences between an American Light Lager fined with gelatin and one fined with Biofine Clear

| METHODS |

Known for being both clear and simple enough to reveal any flaws, I went with an American Light Lager recipe for this xBmt.

Wrong Number

Recipe Details

| Batch Size | Boil Time | IBU | SRM | Est. OG | Est. FG | ABV |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5.5 gal | 60 min | 17.9 | 2.6 SRM | 1.039 | 1.005 | 4.46 % |

| Actuals | 1.039 | 1.005 | 4.46 % | |||

Fermentables

| Name | Amount | % |

|---|---|---|

| Pelton : Pilsner-style Barley Malt (Mecca Grade) | 6.312 lbs | 80.16 |

| Corn, Flaked | 1.562 lbs | 19.84 |

Hops

| Name | Amount | Time | Use | Form | Alpha % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hallertau Magnum | 7 g | 60 min | Boil | Pellet | 14 |

| Saaz | 14 g | 30 min | Boil | Pellet | 3.8 |

Yeast

| Name | Lab | Attenuation | Temperature |

|---|---|---|---|

| Global (L13) | Imperial Yeast | 75% | 32°F - 32°F |

Notes

| Water Profile: Ca 132 | Mg 23 | Na 6 | SO4 260 | 93 |

Download

| Download this recipe's BeerXML file |

I started my brew day by collecting the full volume of water for each batch, adjusting both to my desired mineral profile, then setting the electric controllers to heat them up.

I then weighed out and milled the grain for each batch.

With the water properly heated, I added the grains, turned the pumps on to recirculate, and set the controllers to maintain my intended mash temperature of 148°F/64°C.

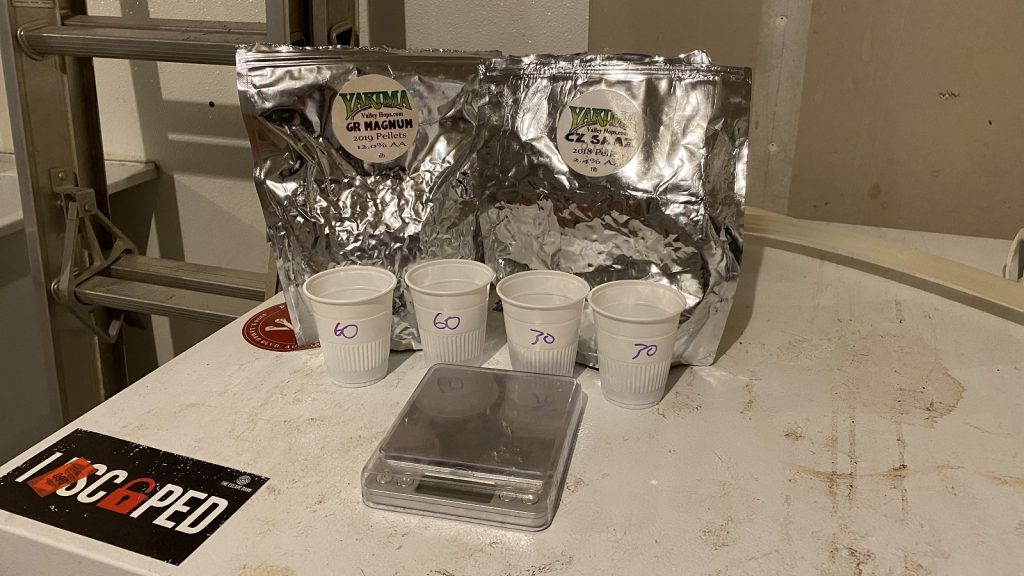

While the mashes were resting, I weighed out the kettle hop additions.

Following each 60 minute mash rest, I raised the grain baskets out of the kettles and let them drain. The worts were then boiled for 60 minutes with hops added at the times listed in the recipe.

When the separate boils were complete, I chilled and combined the worts in the same 14 gallon/53 liter Brew Bucket.

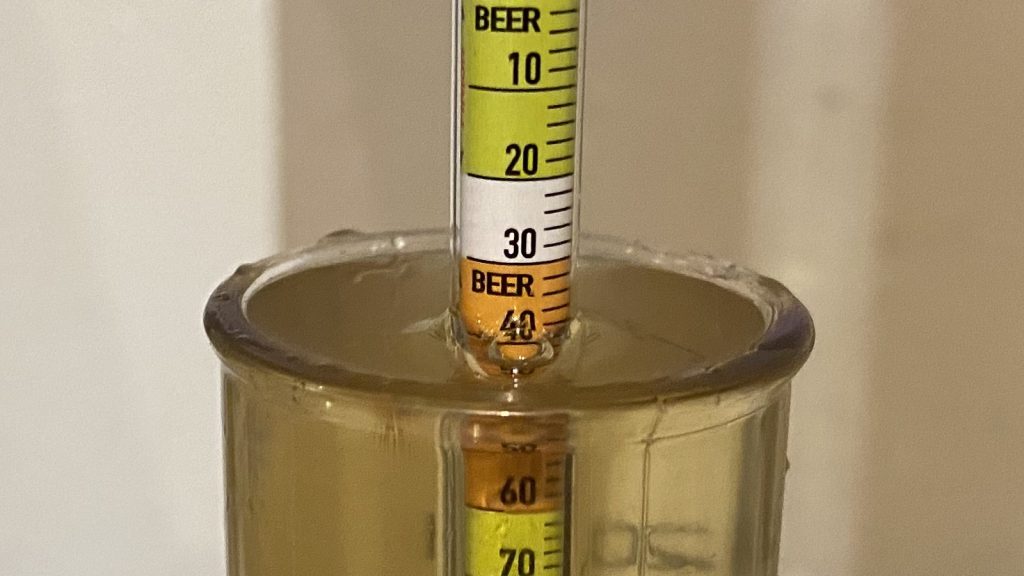

A hydrometer measurement of the homogenized wort showed it was right at my target OG.

The wort was left in my chamber for a few hours to finish chilling to my target fermentation temperature of 55°F/13°C, at which point I pitched 2 pouches of Imperial Yeast L13 Global.

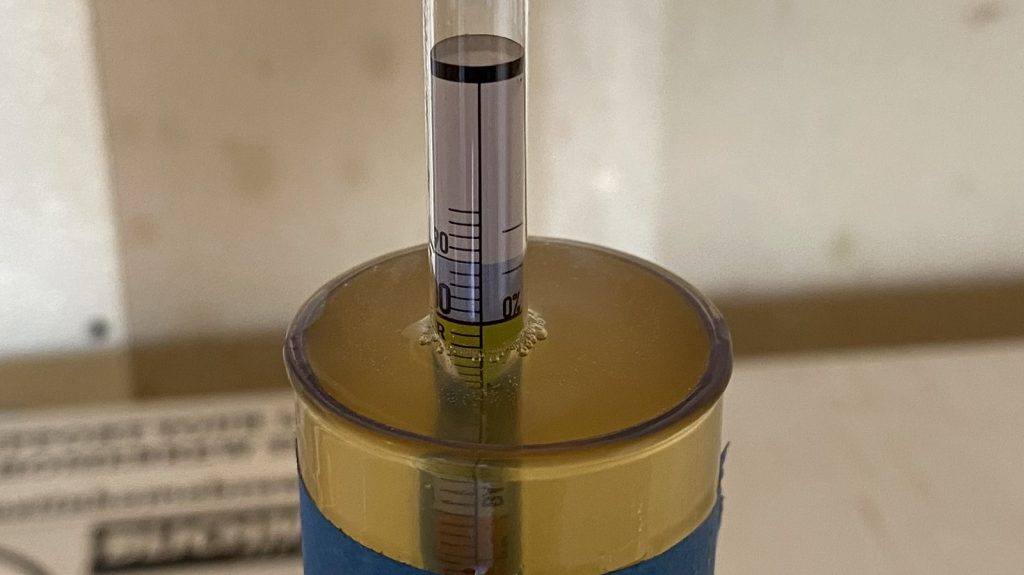

After 5 days of fermentation, I raised the temperature to 64°F/18°C and left it alone for an additional 10 days before taking a hydrometer measurement confirming FG had been reached.

At this point, I cold crashed to 30°F/-1°C overnight before proceeding with packaging, which is when the variable was introduced. Into one of the sanitized kegs, I added a solution of ½ tsp/1.5 g gelatin dissolved in ¼ cup/60 mL hot water, while 1 tbsp/15 mL liquid Biofine Clear was added to another keg.

Both kegs were then purged with CO2 the same number of times to eliminate as much oxygen as possible before the beer was split evenly between them.

The filled kegs were placed on gas in my keezer and allowed to sit for a week before I pulled the first sample, which revealed a noticeable difference in clarity.

After 2 more weeks of cold conditioning, the beer fined with Biofine Clear was certainly less hazy, though the gelatin fined batch was nearly bright.

Even after 6 weeks of cold conditioning, the beer fined with gelatin was clearer than the one fined with Biofine Clear, though they were looking very similar. It was at this point I deemed them ready for evaluation.

| RESULTS |

Due to social distancing practices as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic, data for this xBmt was unable to be collected in our typical manner. As such, temporary adaptations were made involving the author completing multiple semi-blind triangle tests in as unbiased a way as possible.

Utilizing 4 opaque cups of the same color where 2 were inconspicuously marked, one set was filled with the beer fined with gelatin while the other was filled with the beer fined with Biofine Clear. For each triangle test, 3 of the 4 cups were indiscriminately selected, thus randomizing which beer was the unique sample for each trial. Following each attempt, I noted whether I was correct in identifying the unique sample. Out of the 10 semi-blind triangle tests I completed, I needed to identify the unique sample at least 7 times (p<0.05) in order to reach statistical significance. In the end, I correctly identified the unique sample just 4 times (p=0.44), indicating my inability to reliably distinguish an American Light Lager fined with gelatin from one fined with Biofine Clear.

There was nothing dissimilar about these beers to me, both were identically crisp and crushable, despite the one fined with Biofine Clear being ever-so-slightly hazier than the gelatin fined version. This being my first time using Mecca Grade Estate Pelton in such a light style, I was concerned it might be too characterful, but it provided just the right amount of malt flavor to make these beers absolutely delightful.

| DISCUSSION |

It may not be the case for some of the most popular styles of the day, but clarity is a quality many view as imperative for particular styles including most pale lagers. While this was historically achieved by aging beer cold over time, modern brewers have available to them fining agents that quicken the process, two of the most common being gelatin and Biofine Clear. Given their chemical differences, some believe these products impart their own unique flavors to beer, though my inability to reliably distinguish an American Light Lager fined with gelatin from one fined with Biofine Clear indicates any differences were so small as to be imperceptible.

When added to beer, both gelatin and Biofine Clear do essentially the same thing—attract haze causing yeast, proteins, and polyphenols such that they clump together and drop out of solution, leaving only clear beer. One likely explanation for these xBmt results is that nearly all of the fining agent, whether gelatin or Biofine Clear, are removed with the trub, leaving just clear beer. On a more objective level, the gelatin fining did work quite a bit faster than the Biofine Clear, which aligns with my prior experience as well as the findings from a past xBmt.

I’m a big fan of clear beer, especially when it comes to lager styles, and I also appreciate being able to make one without having to wait multiple weeks to start drinking it. I was very pleased with how quickly the gelatin fined beer in this xBmt cleared up and disappointed that the one fined with Biofine Clear never dropped as bright. Because my wife is vegetarian, I’ll be inclined to use Biofine Clear or other veg-friendly fining options when brewing beers she plans to drink, but for everything else, it’ll be cheap and easy-to-use gelatin.

If you have any thoughts about this xBmt, please do not hesitate to share in the comments section below!

Support Brülosophy In Style!

All designs are available in various colors and sizes on Amazon!

Follow Brülosophy on:

FACEBOOK | TWITTER | INSTAGRAM

If you enjoy this stuff and feel compelled to support Brulosophy.com, please check out the Support page for details on how you can very easily do so. Thanks!

20 thoughts on “exBEERiment | Gelatin vs. Biofine Clear In American Light Lager”

I use gelatin with every brew. The no-name brand from Walmart works perfect. The name brands have also been used, and the results are always perfect, clear beer.

I’m not a cloudy / hazy beer fan. And IPA’s are not my cup of tea.

You should compare gelatin to most popular vegan alternative – Agar (agar agar powder). Price and availability similar to gelatin.

It would be interesting to see how much a difference there would be between the biofine and no fining agent to see how much of the clearing was just due to the 6-8 week conditioning vs the dining agent.

this was going ot be my comment too. they need a control group to see if either agent did anything.

Used to be a gelatin user, but then I dabbled into Low Oxygen Brewing and learned about BrewTan B. Using a gram in the mash and then 0.75 grams at 15 minutes in boil, then adding whirlfloc 5 minutes later gives me crystal clear wort after chilling the beer. The BTB and whirlfloc combine to drop all the protein out of suspension right in the kettle. After fermentation, a cold crash drops the beer crystal clear again within 2 days and the once in the keg, beer is usually clear after 1-2 pints once the sediment on the bottom of keg is pulled off. And when I say clear, it’s as clear as professionally filtered beers. As a lot of BTB users say…”clear wort equals clear beer”.

I’ve never tried BrewTan B. It’s something I’d love to play around with.

https://brulosophy.com/2018/02/12/the-brewtan-b-effect-pt-1-immediate-impact-on-various-beer-characteristics-exbeeriment-results/

Biofine works better on Ales. The difference in my brewery is crazy. 1 oz/bbl at transfer and the beer is clear in 2 days.

Lagers are a different story. Biofine helps, but time is what will get them clear. (No filter). In the past, Gelatin clears them up quickly, but we have Vegan food trucks that attract vegan crowds, so we want our beer to be ok for them.

Would love to see this with an ale. Wish I had time to rack three kegs, one each and a control.

Try doubling the amount of biofine and I think results will likely be similar to gelatin

Have you tried agar agar vegetarian gelatin powder? No experience myself.

https://www.amazon.com/agar-powder/s?k=agar+agar+powder

As someone who has used gelatin in my homebrewing, and Biofine in both commercial and homebrewing applications hundreds of times over the better part of the last decade, I notice this experiment sells Biofine a bit short. I have had bright – and less-than-bright – results from each fining agent, but have settled on Biofine as my go-to out of both familiarity and success rate.

I don’t disagree that the shelf-life and ease of storage of gelatin, lesser cost-per-use, wider temperature range and alleged straightforward results from a standard dosage rate probably make it the better option for most homebrewers. If it works for you, stick with it!

However, Biofine works perfectly well – if not better – than gelatin when it’s been stored and used as intended.

Important considerations that directly affect Biofine’s performance, and may have affected its performance in this experiment in particular:

1) It needs to be stored within the 41F-68F temperature range recommended on the label. My experience with these 1kg containers of Biofine is that they’ve been sitting on the shelf in a LHBS at 70-75 degrees, which is a good way to dull its performance.

2) It needs to be used within its 2-year shelf life. Because homebrewers are using only a few mL at a time, the 1kg jugs (a size intended for small commercial brewers, but who often end up purchasing the larger 4kg or 25kg containers) tend to sit longer on the shelf than, say, the smaller 1oz bottles that MoreBeer or NB or Adventures are probably cruising through well within the BBD. Judging by the code ending in “8” listed on the label in the picture, it doesn’t seem unreasonable to believe that this bottle was produced in 2018 (I’m certainly hoping not 2008!) and might be a year past its prime, in addition to possibly being stored outside of its ideal temperature range.

3) The dosage rate can vary from beer to beer. (Really, this is true of any cold-side fining agent.) 15mL in a 5 gallon batch is ~600ppm, which is on the low end of the recommended dosage rate. In the brewery, we would run calibration trials using a small volume pulled from each batch and usually ended up dosing at 500-750ppm as a clarifying step before sending the beer through a plate filter a few days later. Another brewery I talked to that does not filter doses Biofine at around 1000ppm and serves brilliantly-clear beer. Most of my doses end up in the 600-1000ppm range; 600 when I want to leave a touch of dry hop haze intact in an IPA (not unlike what we see in the final side-by-side in this experiment) and 800-1000 in a pilsner or other brilliantly clear style. But this depends on how clear the beer is at the end of its initial conditioning period.

4) It is intended to be used post-conditioning, not pre-conditioning as it is used in this experiment. With this beer, the proper way to use it would be to lager for the 6 weeks, determine the clarity of the beer un-fined, and then determine the consummate dose of Biofine needed to reach the intended clarity. Given my experience doing lagers with Global yeast, which is notoriously difficult to drop out, you’re probably looking at a 25mL dose. Once dosed, it does its work in 2-3 days.

5) It needs to be pretty thoroughly mixed into solution. Whereas gelatin can work great by dosing on top of the beer and allowing it to sink through the beer like a “net” drawing solids to the bottom, Biofine needs to be mixed in to the beer to be most effective. Homebrewers can do this by dosing their keg and gently swirling for a minute or two before allowing it to rest and do its thing.

6) The temperature at which you’re dosing it is also important. It was explained to me once upon time that Biofine Clear is meant as both a non-animal-derived fining agent AND as a way for a brewery to conserve energy, allowing for clearer beer without having to drop it all the way down below 32F. With that in mind: in the brewery, after a string of inconsistent results in the low 30s, we determined that Biofine behaved best at about 37F. So that mid- to upper-30s range is where I now condition, fine, and serve my beer, with good clear results.

Again, I get that a lot of people use gelatin with great results, and those results are exemplified here. But I’ve personally experienced inconsistency with it, and because I’ve been quite familiar with Biofine’s learning curve from the commercial brewing world, I’ve been able to dial it in to my homebrewing processes such that I get the nice clear results shown in the final side-by-side picture more consistently than I ever could with gelatin.

This is fantastic information.

i use https://modernistpantry.com/products/perfectagel-platinum-gelatin-sheets-230-bloom.html slightly higher bloom value than knox at 225

Three days ago I used gelatin on already carbonated and cold beer, and from what I can see through the PET-wall on the unitank, the gelatin (perhaps not all) is stuck on the surface. I flushed the headspace after the addition, and probably the co2 carried the gelatin up to the surface. Anyone having the same experience? I’m eager to see if the beer has cleared up anyway! Hope so!

Some math: a drop is 0.05 ml and a 1/2 t is 2.5 ml. There are 53 12oz servings in 5 gallons which means [2.5/53= 0.047 mil] that each serving has less than a drop. You have got to be nuts to cater to this kind of insanity. It’s not like a peanut allergy that may lead to a trip to the emergency room. It’s people wishing to draw attention to themselves. 40+ years a vegetarian I gotta say the first rule of vegetarianism is ya don’t talk about vegetarianism. When I go to a friends house I eat what they serve, am grateful and know that the most import thing going on is the friendship, generosity and good wishes. It is my experience that home brewers understand this better than most

I know this wasn’t part of the experiment, and there wasn’t a control with a beer that recieved no finings, but was there any noticeable effect to head retention? I’ve read that as proteins are removed yeast can lead to decreased head formation. Thanks and appreciate the article, got my gelatin in the mail for next Helles!

I did not notice any difference between the two, but there wasn’t very much head on this beer to begin with. From personal experience, I haven’t noticed any negative effects on head retention when using finings. If I remember correctly, the haze causing compounds that fall out of solution are different than the foam-positive compounds, so they are largely unaffected. I can’t remember where I read that though.

exactly right. only positively charged particles are attracted

Given that the purpose of the exbeeriment was to determine differences in fining agents, I assume that these agents are chosen because they are known not to impact flavor. Therefore the variable being tested is how the fining agents affect clarity of the finished beer. With that being said, here are some comments.

An important part of the experimental procedure is how the beer was split from the fermenter into the two kegs. Did you take the first half volume out of the fermenter into the first keg and the remaining half into the second keg? What was the method of transfer? Floating dip tube in the fermenter? My point is did both kegs receive an equal amount of trub? This is critical knowledge which should have been shared with the reader. Are the test samples the first beer out of the keg or did you run off a couple of pints first? If kegs were transparent then we could really have seen how these beers cleared up over time. But they’re not, so as a reader we really need you to fill in the gaps for us.

Secondly, the opaque cup semi-blind triangle taste test does not test the variable. The test should have been a crystal clear cup clarity test, where the intensity of light from a know source is measured. Or at least an ocular test with several participants. For this ocular test there is no need to drink the beer just determine which is the clearest, therefore other people from within your “Co-vid bubble” could have been involved in the testing.

Love the exbeeriment, sorry for the rant, keep up the good work!

“I assume that these agents are chosen because they are known not to impact flavor.”

No. The purpose of this exBEERiment was to determine whether there was an impact on flavor and aroma as between the two finings. This was not an experiment to determine their relative effectiveness at clarifying the beers.

Since you asked, when transferring, I always run the first several ounces out of the fermenter until it’s clear so that I don’t transfer trub to the keg. For this experiment, I transferred the hose back and forth between the 2 kegs every few minutes and stopped before any noticeable trub went into either fermenter. When taking samples, I ran several pints out of each keg until the beer was “clear.” I took multiple samples over time as noted in the article.

Regarding your second point, the purpose was not to test how well each fining worked; it was only to test flavor and aroma differences attributable to the finings. So opaque cups were used.

I would love to see a published experiment comparing the efficacy of fining methods, but that is outside the scope of this exBEERiment.

No worries! Rant away. It’s fun to have these kinds of discussions!