Author: Andy Carter

There are various types of specialty malts that can be mashed or steeped in wort to provide color and flavor to beer that are not achievable with base malts alone. Among the most commonly used of these are Caramel malts, which are also commonly referred to as Crystal malts, a distinction that has regional roots—US maltsters make Caramel Malt while UK maltsters produced Crystal Malt.

Caramel and Crystal malts are produced using generally the same process whereby malted barley is either roasted or kilned in the presence of moisture, which degrades most of the starch to sugar, after which the malt spends varying amounts of time drying at different temperatures to achieve the desired color. It should be noted that while Caramel malt can be roasted or kilned, the term Crystal malt is reserved for those that are produced in a roaster, which results in the grain developing a noticeable glassy appearance.

While both Crystal and Caramel malts are known to contribute a similar range of characteristics to beer, from a light candy-like sweetness to rich raisin notes, many believe UK Crystal malts impart a deeper flavor than its US counterparts. With one past xBmt showing tasters were unable to reliably tell apart a simple Pale Ale made with a relatively small amount of either US Caramel or UK Crystal malt, I decided to test it out again in on a more characterful Belgian style.

| PURPOSE |

To evaluate the differences between a Belgian Pale Ale made with US Caramel malt and one made with the same portion of UK Crystal malt of the same color.

| METHODS |

Wanting to isolate the variable as much as possible, I designed a Belgian Pale Ale recipe consisting of a simple grist and hop schedule for this xBmt.

Senne(ic) Stroll

Recipe Details

| Batch Size | Boil Time | IBU | SRM | Est. OG | Est. FG | ABV |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5.8 gal | 60 min | 25 | 8.4 SRM | 1.05 | 1.008 | 5.51 % |

| Actuals | 1.05 | 1.008 | 5.51 % | |||

Fermentables

| Name | Amount | % |

|---|---|---|

| Pale Malt (2 Row) US | 8 lbs | 80 |

| Munich Malt | 1 lbs | 10 |

| US Caramel 60L OR UK Crystal 60L | 1 lbs | 10 |

Hops

| Name | Amount | Time | Use | Form | Alpha % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sterling | 23 g | 60 min | Boil | Pellet | 8.6 |

| Saphir | 28 g | 20 min | Boil | Pellet | 2.8 |

Yeast

| Name | Lab | Attenuation | Temperature |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gnome (B45) | Imperial Yeast | 78% | 32°F - 32°F |

Notes

| Water Profile: Ca 47 | Mg 5 | Na 8 | SO4 71 | Cl 48 |

Download

| Download this recipe's BeerXML file |

I started my brew day by adding identical volumes of RO water to separate BrewZilla units then setting the controller to heat it up.

After adding the same amount of minerals to each kettle, I milled the grains into separate buckets.

Once the water for each batch was adequately heated, I incorporated the grains then checked to make sure both were at the same target mash temperature.

At 15 minutes into each mash, I pulled samples to measure the pH and found the US Caramel malt wort was slightly lower than the UK Crystal malt wort.

While the mashes were resting, I prepared the kettle hop additions.

Once each 60 minute mash was complete, I sparged to collect the same pre-boil volume then boiled the worts for 60 minutes before running them through a plate chiller.

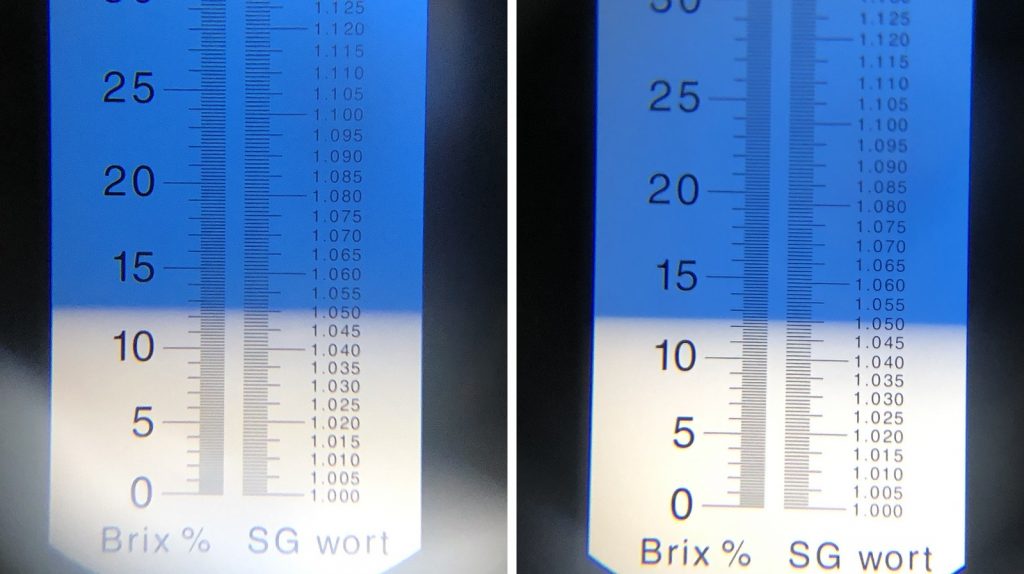

Refractometer readings showed both worts achieved the same target OG

The filled carboys were placed in my chamber and left to finish chilling to my desired fermentation temperature of 64°F/18°C for a few hours before I pitched a pouch of Imperial Yeast B45 Gnome into each.

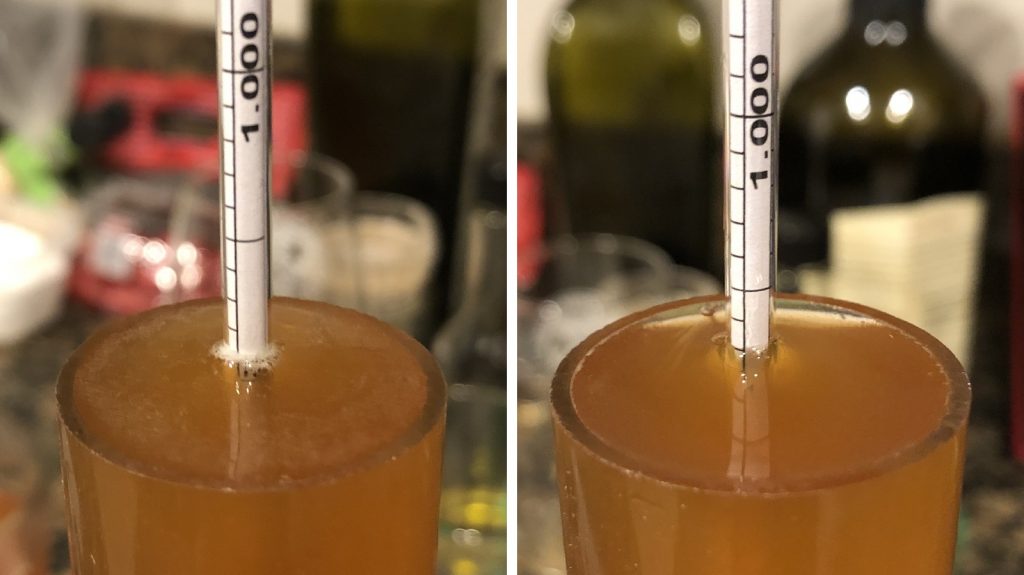

After a week, I raised the temperature in the chamber to 70°F/21°C and let it sit for an additional week before taking hydrometer measurements showing a the beer made with US Caramel malt finished 0.001 SG point lower than the UK Crytal malt beer.

At this point, I racked the beers to sanitized kegs.

The filled kegs were placed in my keezer and left on gas for 3 weeks before I began my evaluations.

| RESULTS |

Due to social distancing practices as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic, data for this xBmt was unable to be collected in our typical manner. As such, temporary adaptations were made involving the author completing multiple semi-blind triangle tests in as unbiased a way as possible.

Utilizing 4 opaque cups of the same color where 2 were inconspicuously marked, one set was filled with the beer made with US Caramel malt while the other set was filled with the beer made with UK Crystal malt. For each triangle test, 3 of the 4 cups were indiscriminately selected, thus randomizing which beer was the unique sample for each trial. Following each attempt, I noted whether I was correct in identifying the unique sample. Out of the 10 semi-blind triangle tests I completed, I needed to identify the unique sample at least 7 times (p<0.05) in order to reach statistical significance. Ultimately, I identified the unique sample 6 times (p=0.44), indicating my inability to reliably distinguish a Belgian Pale Ale made with US Caramel from one made with UK Crystal malt of the same color.

These beers were certainly far more similar than they are different, which explains my inability to distinguish them enough in my series of triangle tests to achieve significance. Both display pleasant phenols that meld well with toasty and caramel notes from the caramel and crystal malts used, making it reminiscent of ginger cinnamon cookies. While I personally felt the phenols were a bit too high for a proper Belgian Pale Ale, I enjoyed these beers quite a bit and found them very easy to drink.

| DISCUSSION |

Specialty grains are a tool brewers often use to fine-tune their recipes, adding color and flavors that cannot be achieved with base malts alone. Caramel and Crystal malts are such ingredients, often used in relatively small amounts to increase depth of flavor, and while viewed as being largely identical by some, others claim US Caramel malts impart noticeably different characteristics than UK Crystal malts. My inability to reliably distinguish a Belgian Pale Ale made with 10% US Caramel malt from one made with the same amount of UK Crystal of the same color suggests any differences were so small as to be undetectable.

The fact these results corroborate those from a past xBmt on the same topic adds more credence to the idea that, even if the production process is slightly different, US Caramel and UK Crystal malts have the same perceptible impact on beer. Some may be looking at my performance and thinking that 6 out of 10 correct selections is pretty good, and that’s fine, we’re all free to do what we want with this data, but I think it’s important to note I was massively biased by my awareness of the variable. It’s possible that using higher amounts of these specialty malts would lead to greater differences, which is certainly worth exploring more in the future.

I’ve always factored the source of my ingredients while designing recipes, and while I continue to do so as it pertains to specialty malts, these experience left me feeling less concerned about the potential differences between US Caramel and UK Crystal malts. Seeing as my typical usage rates for these malts generally falls under 10% of the grist, I’m compelled to go with the version I either have on-hand or is less expensive in the future.

If you have any thoughts about this xBmt, please do not hesitate to share in the comments section below!

Support Brülosophy In Style!

All designs are available in various colors and sizes on Amazon!

Follow Brülosophy on:

FACEBOOK | TWITTER | INSTAGRAM

If you enjoy this stuff and feel compelled to support Brulosophy.com, please check out the Support page for details on how you can very easily do so. Thanks!

8 thoughts on “exBEERiment | Grain Comparison: US Caramel vs. UK Crystal Malt In A Belgian Pale Ale”

Shouldn’t you have had a baseline beer with a very light crystal malt, to see what the influence of the Munich malt actually is? Because now you can’t really know if this outcome is due to the crystal and caramel malts being indistinguishable, or if the Munich malt suppresses all differences.

And a Belgian yeast can certainly mask a lot of malt character as well. This is something I’d love to see tested on a bigger and more controlled scale, because I don’t necessarily see a lot of value in this particular version of the experiment.

Since I’ve often heard the claim expressed as “you need an English Crystal malt for an English ale”, a good test recipe would be a moderately hopped bitter. Something like 90% Golden Promise/10% US or UK C-60, 30ish IBU of EKG, and an English ale yeast (ideally something with a bit less esters like WLP013 to let more of the Crystal malt character shine through).

As Andy said, there is definite skew in the results on the part of the brewer who knows the variable. I know I can tell a difference when I taste a couple of kernels of Briess C-60 and Baird’s C-60 side-by-side. Armed with that knowledge I feel like I have a better chance of picking out the difference in my finished beer, but even that’s no guarantee. Would someone else detect it? I’m less confident of that.

Plus 1 to Eric’s comment. After using Crystal 60s as typical adjunct in most brews, I was with a friend at the LHBS. We were going to brew a lager for him (which was departure from my usual ales) He had a 50 year old recipe that his dad used to brew. It called for Caramel 60. We tasted a bit as well as the Crystal 60. We both liked the Caramel better & used it. Now it’s my go-to & I just think I taste the difference in the beers.

I really would love to see this done again post-covid when it can be tested by different people.

Would be helpful to identify whether the US C60 you used was a drum roasted Crystal Malt or a Kilned Caramel Malt. There is a significant flavor difference between the two production methods.

You guys should do an exbeeriment testing a brew day where you are legless drunk on homebrew vs a sober brew day, whenever I drink too much on my brew days the next day I’m always questioning what I’ve even brewed, no measurements etc just a fermenter full of something in the fridge haha

“Out of the 10 semi-blind triangle tests I completed, I needed to identify the unique sample at least 7 times (p<0.05) in order to reach statistical significance. Ultimately, I identified the unique sample 6 times (p=0.44)…"

Is that p-value correct? I'll admit to not being real familiar with this type of statistical testing, but if 7/10 gives p<0.05, it doesn't seem likely that one fewer correct selection would raise the p-value all the way to 0.44. Granted, even if the p-value is a typo, it doesn't alter the conclusion at all since regardless 6/10 is above the p-value threshold for significant.

Resurrecting an old topic…..

What about the impact the water profile had on the results? With the SO4 to Cl ratio of nearly 2:1, the bitterness of the hops was being enhanced rather than the maltiness of the Caramel/Crystal, which could have suppressed the differences. Not suggesting going for a 0.5:1 ratio, but would a balanced 1:1 water profile have made any difference?