Author: Jake Huolihan

Brettanomyces (Brett) is a wild yeast that historically was largely considered a spoilage microbe, though these days, brewers rely on certain strains to produce beers with unique characteristics ranging from horse blanket to overripe tropical fruit. While fermenting beer entirely with Brett has grown in popularity over the years, it’s more commonly used in conjunction with Saccharomyces, often being added once primary fermentation is complete and the beer is in the package. Another method involves pitching the Brett alongside the Saccharomyces so that both are present during primary fermentation,

As with most things in brewing and life, there are purported pros and cons to both of these methods. By pitching Brett post-fermentation, not only is the risk of contaminating the primary fermentation vessel reduced by racking the beer to another vessel for inoculation, but many believe this leads to a more consistent end product. However, others contend that co-pitching Brett with Saccharomyces produces a beer with greater overall complexity.

After recently reading an article on historical British beer that discussed the near certainty with which most was infected with Brett, among other microbes, I was inspired to brew a batch to experience for myself what such a beer tastes like. Given fermentation practices of the day, it’s highly probably fermentation occurred in the presence of both the intended Saccharomyces as well as wild Brettanomyces. With a past xBmt showing tasters could distinguish a Golden Sour Ale where the Saccharomyces was co-pitched with other microbes from one where the pitch times were staggered, I decided to test this one out again.

| PURPOSE |

To evaluate the differences between a British Ale pitched with Brettanomyces post-fermentation from one where the Brettanomyces is co-pitched with Saccharomyces.

| METHODS |

My goal being to experience what the British Ale of yore possibly tasted like, I designed a recipe for this xBmt that stylistically falls between Bitter and English IPA.

Crooked Teeth

Recipe Details

| Batch Size | Boil Time | IBU | SRM | Est. OG | Est. FG | ABV |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5.5 gal | 30 min | 49.9 IBUs | 14.1966304 | 1.059 | 1.015 | 5.8 % |

| Actuals | 1.059 | 1.013 | 6.1 % | |||

Fermentables

| Name | Amount | % |

|---|---|---|

| Genie Pale Malt | 14 lbs | 94.92 |

| Carahell (Weyermann) | 8 oz | 3.39 |

| BlackPrinz | 4 oz | 1.69 |

Hops

| Name | Amount | Time | Use | Form | Alpha % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cryo - Loral | 25 g | 30 min | Boil | Pellet | 19.5 |

| East Kent Goldings (EKG) | 33 g | 15 min | Boil | Pellet | 5 |

| East Kent Goldings (EKG) | 33 g | 5 min | Boil | Pellet | 5 |

Yeast

| Name | Lab | Attenuation | Temperature |

|---|---|---|---|

| House (A01) | Imperial Yeast | 74% | 62°F - 70°F |

| Suburban Brett (W15) | Imperial Yeast | 78% | 64°F - 74°F |

Notes

| Water Profile: Ca 91 | Mg 0 | Na 8 | SO4 149 | Cl 55 |

Download

| Download this recipe's BeerXML file |

I made a starter with of Imperial Yeast W15 Suburban Brett a week ahead of time and observed noticeable signs of growth 3 days later.

On brew day, after adjusting the RO water to my desired profile and getting it heating up, I weighed out and milled the grain.

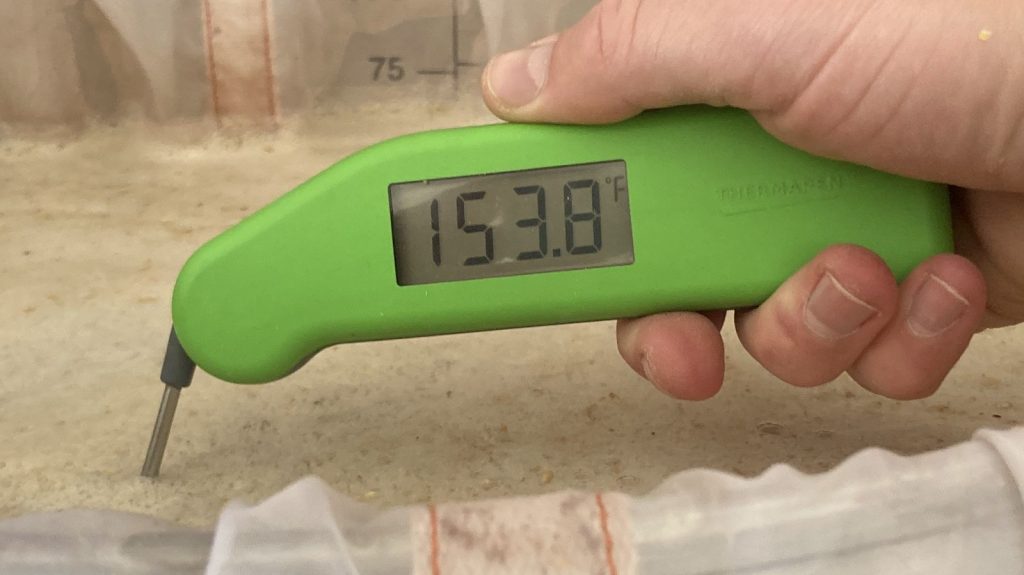

With the water properly heated, I mashed in then checked to ensure it was at my target temperature.

During the 60 minute mash rest, I returned every 15 minutes to give it a brief stir.

While waiting on the mash to finish, I prepared the kettle hop additions.

Once the mash was complete, I collected the sweet work in my kettle and proceeded to boil it for 30 minutes.

When the boil was finished, I quickly chilled the wort with my IC.

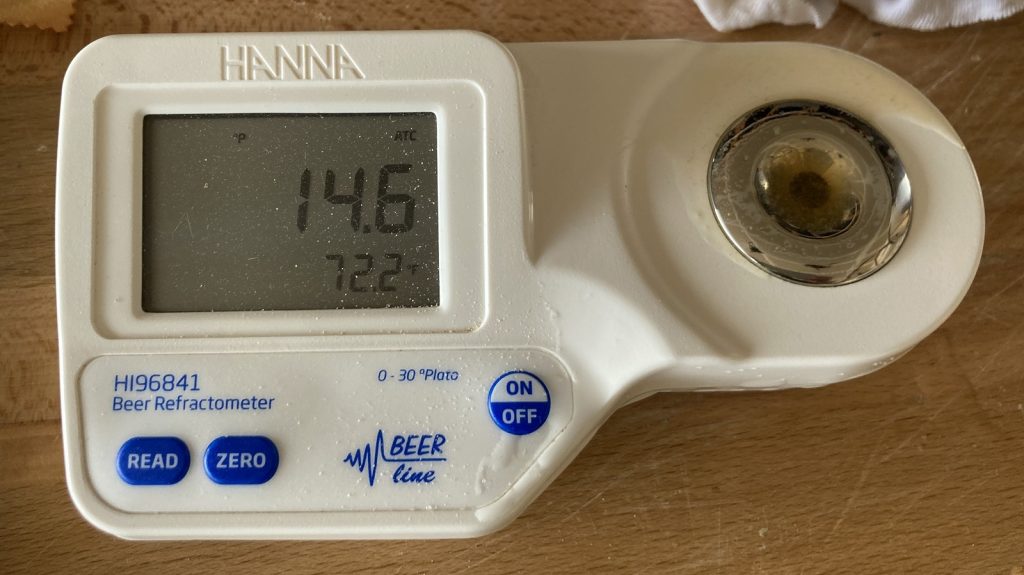

A refractometer reading showed the wort was right at my intended OG.

The wort was evenly split between two fermentation vessels where I relied on my glycol unit to further chill each to my desired fermentation temperature of 64°F/18°C. At this point, I pitched a single pouch of Imperial Yeast A01 House into each batch before adding the starter of Imperial Yeast W15 Suburban Brett into just one of them.

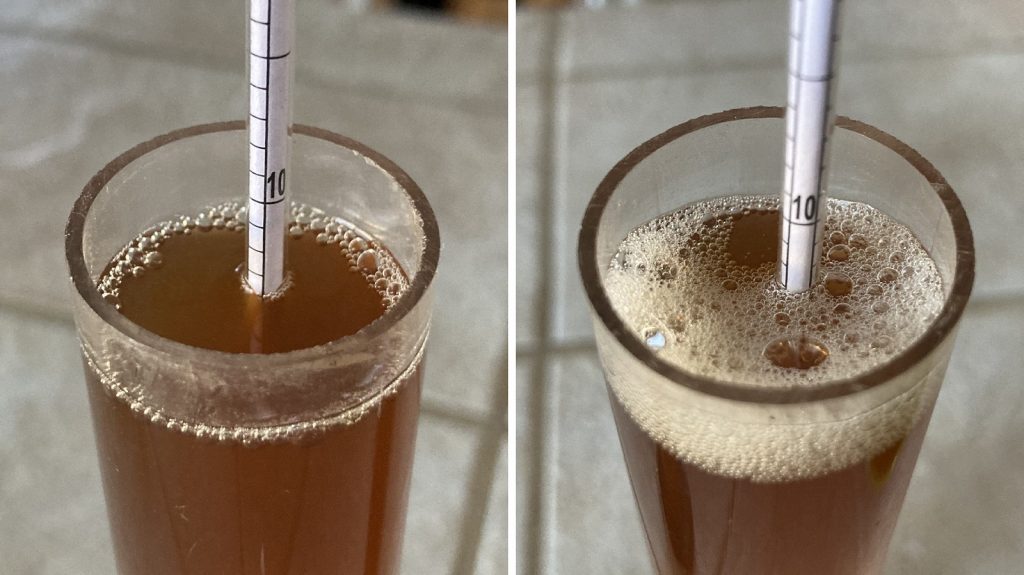

After cleaning up, I made a second starter of Imperial Yeast W15 Suburban Brett. A week into fermentation, I took hydrometer measurements showing the co-pitch beer was 0.003 SG points higher than the beer fermented with just Saccharomyces, which I thought might be an error caused by the amount of sediment in suspension.

I proceeded to pitch the second starter of Imperial Yeast W15 Suburban Brett into the staggered pitch batch. After 10 more days, I took hydrometer measurements showing both beers had settled at the same FG.

Next, my assistant helped me pressure transfer the beers to CO2 purged kegs.

The filled kegs were placed in my keezer and left to carbonate for a couple weeks before they were ready for evaluation.

| RESULTS |

Due to social distancing practices as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic, data for this xBmt was unable to be collected in our typical manner. As such, temporary adaptations were made involving the author completing multiple semi-blind triangle tests in as unbiased a way as possible.

Utilizing 4 opaque cups of the same color where 2 were inconspicuously marked, one set was filled with the co-pitch beer while the other set was filled with the staggered pitch beer. For each triangle test, 3 of the 4 cups were indiscriminately selected, thus randomizing which beer was the unique sample for each trial. Following each attempt, I noted whether I was correct in identifying the unique sample. Out of the 10 semi-blind triangle tests I completed, I needed to identify the unique sample at least 7 times (p<0.05) in order to reach statistical significance. In the end, I correctly identified the unique sample all 10 times (p= <0.00001), indicating my ability to reliably distinguish a British Ale that was pitched with both Saccharomyces and Brettanomyces at the same time from one where Brettanomyces was pitched following primary fermentation with Saccharomyces.

Both of these beers possessed easily identifiable Brett characteristics of pepper and barnyard, though I perceived notably less complexity in the co-pitch batch, which is what made distinguish them so easy for me. While I definitely enjoyed drinking these beers, much of that stemmed from my original aim of experiencing what beer tasted like in the not-so-distant past, so I won’t be brewing this recipe again in the future.

| DISCUSSION |

Once ubiquitously viewed as a bogeyman of beer, the use of Brettanomyces has grown massively over the years, with lovers-of-funk relying on it to produce beers with unique characteristics unattainable when fermenting with just Saccharomyces. This popularity is evidenced by the highly active Milk The Funk group whose members have arguably done more to advance our understanding of sour and funky brewing than anyone else. While many prefer adding Brett to beer following Saccharomyces fermentation, others claim to get more desirable characteristics by fermenting with both Brett and Saccharomyces. My ability to reliably distinguish a British Ale that was co-pitched with Brett and Saccharomyces from one where the Brett was pitched post-fermentation supports the notion each method produces a unique result.

While the mechanics of fermentation are rather well understood, particularly as it pertains to Saccharomyces, finding a definitive explanation as to why co-pitching Brett produces different characteristics than pitching when fermentation is complete proved difficult. Curiously, I perceived the co-pitch beer as possessing less character than the staggered pitch batch, which goes against the claims of many. Considering these results align with those from a past xBmt comparing co-pitching to staggered pitching, I’m wont to believe the differences I perceived were a result of the variable and not something else.

While I appreciate the uniqueness Brettanomyces can impart and enjoyed drinking the beers from this xBmt, I have a strong preference of cleaner styles and hence stick to using Saccharomyces in the good majority of brewing. In the rare times I brew funky beers in the future, I’ll be using the staggered pitch approach, as I felt it led to a more prominent Brett character compared to pitching Brett and Saccharomyces together.

If you have any thoughts about this xBmt, please do not hesitate to share in the comments section below!

Support Brülosophy In Style!

All designs are available in various colors and sizes on Amazon!

Follow Brülosophy on:

FACEBOOK | TWITTER | INSTAGRAM

If you enjoy this stuff and feel compelled to support Brulosophy.com, please check out the Support page for details on how you can very easily do so. Thanks!

5 thoughts on “exBEERiment | Impact Of Co-Pitching Brettanomyces and Saccharomyces In A British Ale”

Regarding the process of chilling the boiled wort as quickly as possible with special chilling devices. This is done for every Exbeeriment I’ve read and seems to be taken as absolutely necessary. I’d be interested to know if this has been tested out on Brulosophy. I just leave my wort to gradually cool down to room temperature overnight and don’t have any problems that I’ve come across. I brew low carbonated British ale at about 3.5-4% alcohol and bottle it with secondary fermentation in the bottle. It’s designed to be drunk a little cooler than room temperature, equivalent to ‘cellar’ temperature; maybe about 55°F, so there is also no need to chill it down to low temperatures during maturation.

There’s been a couple no-chill experiments

https://brulosophy.com/2020/02/27/cooling-the-wort-no-chill-method-vs-rapid-chilling-in-an-ipa-the-bru-club-xbmt-series/

https://brulosophy.com/2015/11/09/cooling-the-wort-pt-1-no-chill-vs-quick-chill-exbeeriment-results/

We’re completely off topic here Chrisgg (apologies, Jake) but you raise an interesting point. I’m not so sure about your assertion that – because you’re drinking the beer relatively warm – you can therefore mature it at a warmer temperature too. I was under that same impression but a well respected local brewer who’s gone commercial (for what that’s worth) told me: no, even if you like to drink bottle conditioned beer at 13°C (as we call it here in the UK), you should still store it as cold as possible to best preserve freshness and flavour. (Note: I’m talking about storage _after_ warm conditioning here.)

Drew and Denny were discussing this very subject on their podcast at one point. I can’t remember who they were quoting but this person was saying that the reason you get more ‘Brett’ character in the later brett addition is because the sacch has already fermented most of the easily accessible extract, leaving Brettanomyces to use different metabolic pathways to chew on leftover dextrins etc. The alternate metabolism results in much stronger character. If Brett is copitched, it will produce cleaner flavor while having access to the same O2 and simple sugars that the sacch does, fermenting using its preferred metabolic pathways, unstressed in a more hospitable environment.

This is apparently why 100% Brett fermented beers can be so clean.

That was a really short fermentation period with the brett in my personal experience and the FG of 1.013 is insanely high considering what i’m used to.