Author: Andy Carter

When crafting a beer recipe, brewers tend to focus most on the big 4 ingredients– water, malt, hops, and yeast. However, another important aspect that contributes to the ultimate character of a beer is carbonation. Whereas some styles call for lower levels of fizz, others are expected to possess higher amounts of carbonation, one notable style being Saison.

While the most common carbonation method in the modern brewing era involves forcing external CO2 into solution, naturally carbonating beer through the use of priming is viewed by many as an essential component to producing a quality Saison. Such a process relies on the remnant yeast in beer that’s finished fermenting consuming the priming sugar, thus producing CO2 that gets forced into solution due to the vessel being sealed. Proponents of natural carbonation have claimed the bubbles produced using this approach are finer and produce a creamier head, both desirable traits in Saison as well as other styles.

I force carbonated the good majority of my beers because it’s really easy and requires less time than natural conditioning. However, I’ve remained open to the possibility that the two methods produce a noticeable difference, despite the results from a past xBmt indicating it had little impact on an American IPA. With a Saison on the brewing deck, I decided I’d take the opportunity to test this one out again on style believed by many to benefit from natural carbonation.

| PURPOSE |

To evaluate the differences between a Saison naturally carbonated in the keg and one force carbonated to the same volume of CO2.

| METHODS |

I went with a fairly standard Saison recipe for this xBmt, keeping things simple in hopes of accentuating any differences caused by carbonation method.

Season Of The Dissolved

Recipe Details

| Batch Size | Boil Time | IBU | SRM | Est. OG | Est. FG | ABV |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5.5 gal | 60 min | 72.9 IBUs | 3.3 SRM | 1.052 | 1.010 | 5.5 % |

| Actuals | 1.052 | 1.003 | 6.5 % | |||

Fermentables

| Name | Amount | % |

|---|---|---|

| Pilsner (2 Row) Ger | 6 lbs | 60 |

| Pale Malt (2 Row) US | 4 lbs | 40 |

Hops

| Name | Amount | Time | Use | Form | Alpha % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sterling | 9 g | 60 min | Boil | Pellet | 11.6 |

| Ella | 14 g | 30 min | Boil | Pellet | 17.7 |

| Sterling | 9 g | 30 min | Boil | Pellet | 11.6 |

| Ella | 20 g | 15 min | Boil | Pellet | 17.7 |

| Sterling | 20 g | 15 min | Boil | Pellet | 11.6 |

Yeast

| Name | Lab | Attenuation | Temperature |

|---|---|---|---|

| Rustic (B56) | Imperial Yeast | 74% | 68°F - 80°F |

Notes

| Water Profile: Ca 47 | Mg 5 | Na 8 | SO4 71 | Cl 48 |

Download

| Download this recipe's BeerXML file |

After collecting two equal volumes of RO water, adjusting them to the same profile, and turning the elements on to heat them up, I weighed out and milled two identical sets of grain.

When each batch of water reached their respective strike temperatures, I stirred in the grains then checked to make sure both were at my target mash temperature.

The mashes were then left to rest for 60 minutes.

During the wait, I weighed out the kettle hop additions.

When each mash rest was complete, I batch sparged to collect the same volume of wort then boiled them for 60 minutes before chilling.

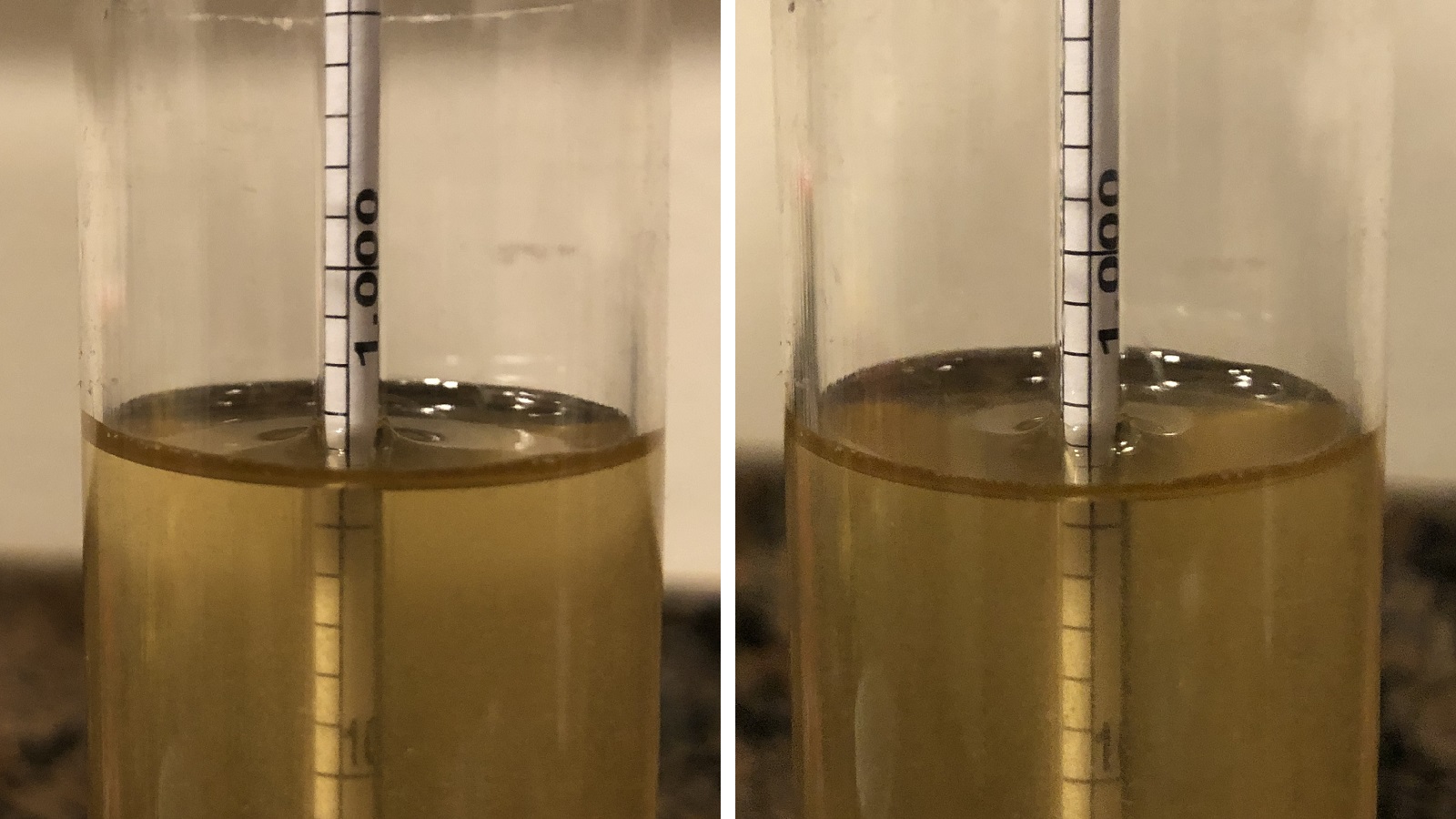

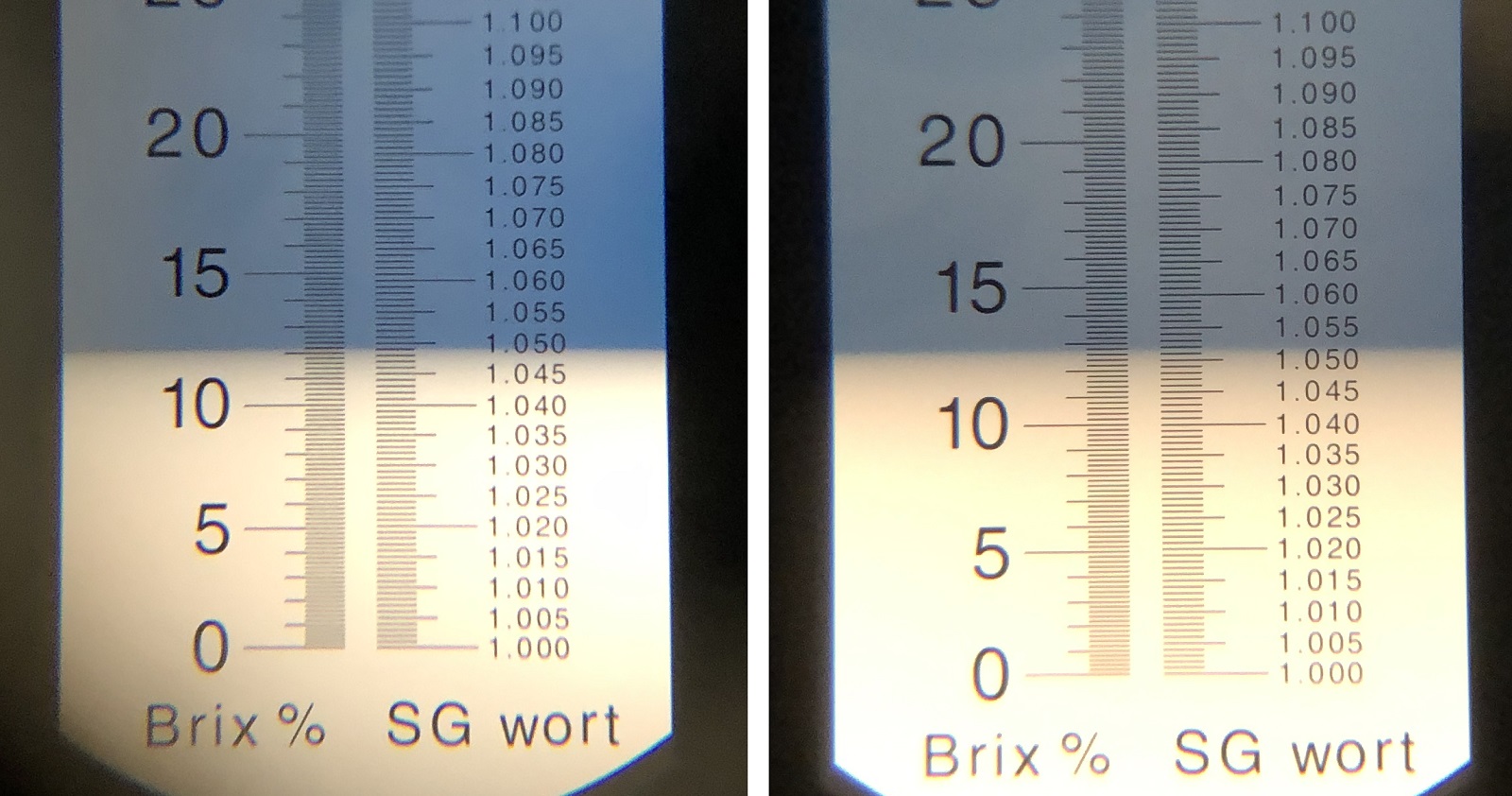

Refractometer readings showed a very slight difference of about 0.002 OG.

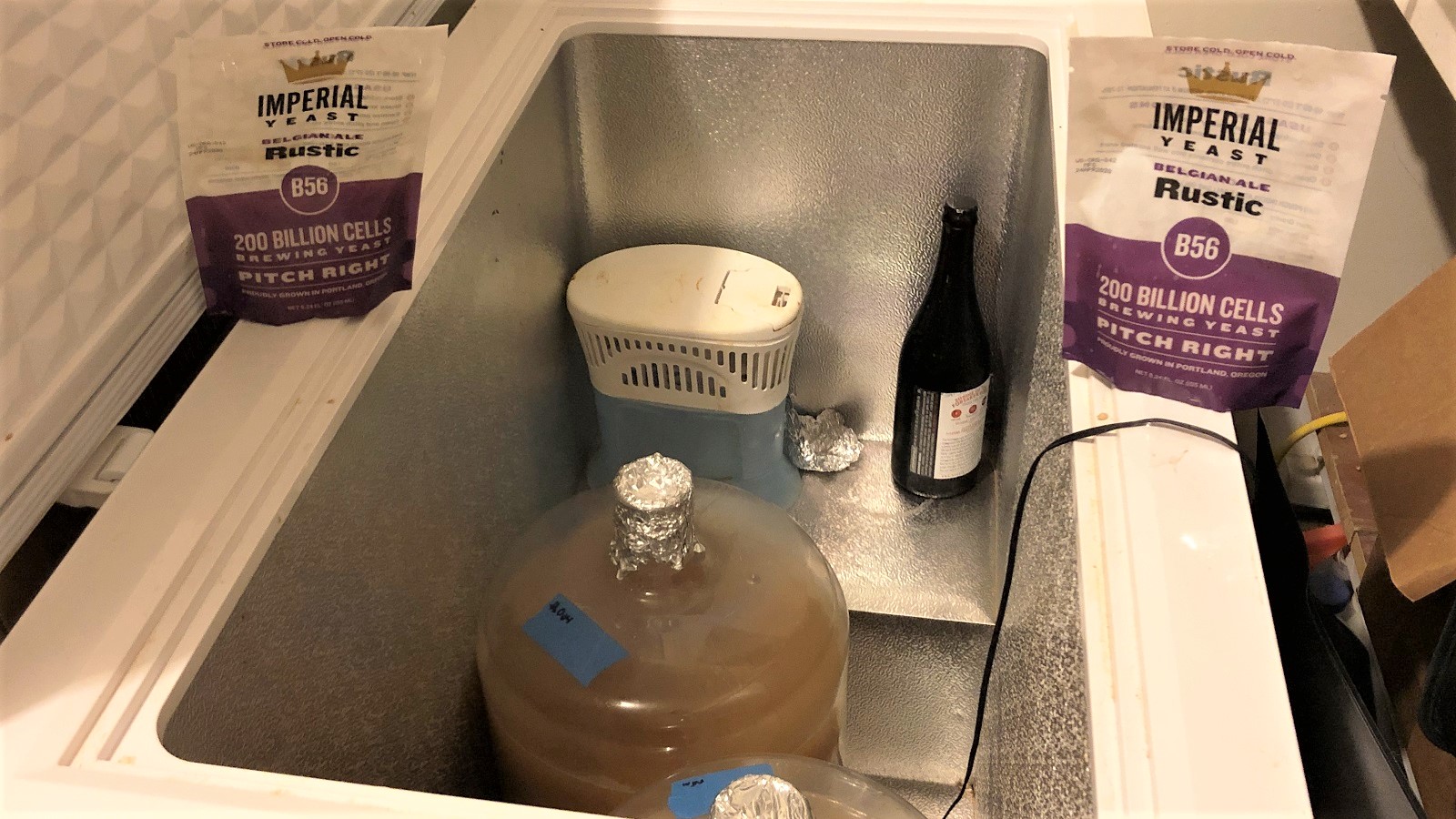

Equal amounts of wort were racked to sanitized 6 gallon/23 liter PET carboys that were placed in my fermentation chamber and allowed to finish chilling. With the worts at 70°F/21°C a couple hours later, I pitched a single pouch of Imperial Yeast B56 Rustic into each batch.

The beers fermented similarly over the next 5 days, at which point I raised the temperature in the chamber to 75°F/24°C to encourage complete attenuation. The beers were left alone for another week before I took hydrometer measurements confirming both reached the same FG.

The beers were then racked to sanitized kegs.

With the kegs filled, I proceeded to prepare the priming sugar for the naturally conditioned batch. Given the volume of beer and my desired carbonation level of approximately 3 volumes, I determined I would need to use 120 grams of dextrose priming sugar.

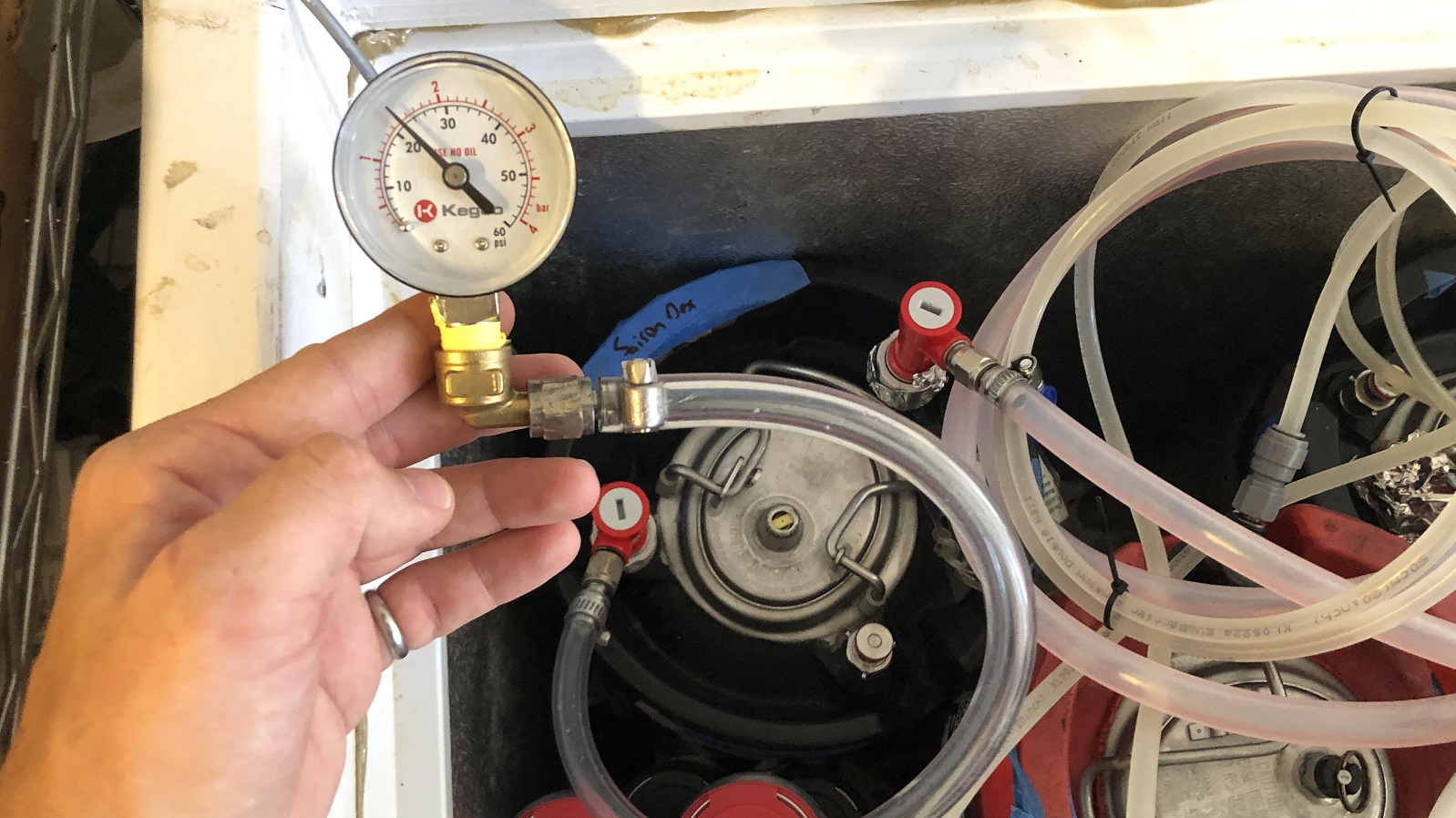

While the naturally conditioned beer was put in a spot that maintains a fairly consistent 70°F/21°C, the force carbonated beer was placed in my 40°F/4°C keezer and hit with 12 psi of CO2. After 2 weeks, I gently moved the naturally conditioned beer to the keezer then, after letting it cool for a few hours, used a gauge to test the headspace pressure, which was 22 psi.

After connecting a 22 psi gas line to the keg conditioned beer, I upped the pressure on the force carbonated beer to 22 psi to ensure similar levels of carbonation. The beers were left alone for 9 days before I began evaluating them.

| RESULTS |

Due to social distancing practices as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic, data for this xBmt was unable to be collected in our typical manner. As such, temporary adaptations were made involving the author completing multiple semi-blind triangle tests in as unbiased a way as possible.

Utilizing 4 opaque cups of the same color where 2 were inconspicuously marked, one set was filled with the naturally carbonated beer while the other set was filled with the force carbonated beer. For each triangle test, 3 of the 4 cups were indiscriminately selected, thus randomizing which beer was the unique sample for each trial. Following each attempt, I noted whether I was correct in identifying the unique sample. Out of the 10 semi-blind triangle tests I completed, I needed to identify the unique sample 7 times (p<0.02) in order to reach statistical significance. In the end, I chose the unique sample just 4 times (p=0.44), indicating my inability to reliably distinguish a Saison that was naturally carbonated in the keg from one that was force carbonated.

I was quite pleased with how these beers turned out and perceived them as having balanced fruity and pepper aroma I enjoy in a good Saison. Similarly, the flavor was a nice combination of low to medium phenols and esters with a bit of the hop character peeking through. Having never use Imperial Yeast B56 Rustic, I wasn’t sure what to expect and was happy with the results!

| DISCUSSION |

Most commonly viewed as a method employed by new homebrewers, naturally carbonating beer through either bottle or keg conditioning is believed by many to produce desirable results in terms of bubble size and foam, particularly for highly carbonated styles like Saison. Interestingly, I was unable to reliably tell apart a keg conditioned Saison from one that was force carbonated to the same volume of CO2.

I was admittedly rather surprised with these results, especially considering I brewed the beers and was fully aware of the variable being tested. Despite my biased eyes and palate looking for differences in foam and fizz, I simply could not find any, the beers were identical to me. While this calls into question the claims of those who preach the perceptible benefits of natural carbonation, it’s nice to know that either method can be used to produce a good beer, which can come in handy for those with limited space to store full kegs.

Personally, while I wouldn’t refrain from keg condition the occasional Belgian ale, it’s not a method I’ll be using with any regularity. Understanding that re-fermentation in a keg results in some scrubbing of oxygen, I have concerns about leaving beer at warmer temperatures for too long, especially lighter and dry hopped styles. Seeing as I possess all the proper gear, force carbonation is just easier and less time consuming, but I appreciate knowing I can use natural carbonation methods as a solid backup.

If you have any thoughts about this xBmt, please do not hesitate to share in the comments section below!

Support Brülosophy In Style!

All designs are available in various colors and sizes on Amazon!

Follow Brülosophy on:

FACEBOOK | TWITTER | INSTAGRAM

If you enjoy this stuff and feel compelled to support Brulosophy.com, please check out the Support page for details on how you can very easily do so. Thanks!

14 thoughts on “exBEERiment | Carbonation Methods: Keg Conditioning vs. Force Carbonation In A Saison”

I’m not surprised at all. How does Rustic compare with the other popular Saison strains? Is there much bandaid-chemical-smoke phenol character?

I’m a big fan of Rustic/ Wyeast 3726 both reported to be the Blaugies strain. It just seems to give a little more balanced saison profile. As Andy said fruity/peppery. I pitch at 65F and hold it 68-70 for a couple of days before slowly ramping to 80 over 10 days.I open ferment for 5 days (foil taped over the airlock hole on my Brewbucket) before adding an airlock. Keeping your ferment temps on the low side should help prevent strong flavor and fusel alcohol production which can happen when you start high and let her rip.

cool! thanks!

2 months ago I used Rustic on a recipe that I normally make with Wyeast 3724 and found the Rustic version disappointingly bland by comparison. There was no “bandaid-chemical-smoke phenol character” in the Rustic and I have not had that using the 3724 strain.

“Understanding that re-fermentation in a keg results in some scrubbing of oxygen”.

I know it’s one of this things that we read everywhere, but are you sure about that?

My understanding is that the yeasts use oxygen early on to help with building cell walls and growth, but I don’t think they use much past this stage.

I could be wrong but I would be surprised if there is much cell growth involved during bottle/keg conditioning.

from Wikipedia: “Because yeasts perform this conversion in the absence of oxygen, alcoholic fermentation is considered an anaerobic process.”

Anyway, keep them coming! Your blind tests are one of the only source of information about homebrewing that doesn’t require blindly trusting an authority.

Since the beer is at FG before going into the keg, I would think the yeast are likely going dormant and starting a brand new reproduction cycle once a new sugar source is added. I’m also not sure if they *only* consume oxygen during the initial growth phase. I think that, as long as they are actively fermenting something, they will consume oxygen when they find it.

I saw some data from the low oxygen brewing page using yeast to scrub O2 from strike water, and the yeast are consuming all of it within an hour or less, and can hold the water at 0ppm for several days.

The whole force vs natural carbonation debate has always seemed needless. By either method CO2 is being “forced” into solution. To argue which is “better” is a waste of time.

Similar results as yours doing my own tasting experiments over the years. I will say, My hefe’s are bottle conditioned to ~4.2 volumes. I’ve tried kegging one to that level and ended up having half my beer spray across the garage. The only time I keg condition when I don’t have an open CO2 connection. Chill to 35F for a week, check the pressure, bleed it if need be, and voila, nicely carbed beer without having to use my CO2.

I was very curious to hear about how this would turn out as I love to brew/ferment saisons. Thank you for weighing in on this. Once you get into the ease of force carbonation it is hard to go back to bottle conditioning.

The keg condition (I rarely bottle these days) when I want to add depth of flavor and CO2 by conditioning on Honey/Belgian Candi Syrup/etc… One in a while I’ll condition kegs with corn sugar if I’m low on CO2 😉

Wouldn’t keg conditioning just be force carbonating anyway? My thoughts are that the yeast will produce the CO2 which will build pressure in the headspace and then when the headspace pressure>dissolved CO2 pressure, they will slowly equalise. The same principle as force carbonating. My opinion would be the biggest difference would end up being the slight ABV% bump and some extra trub in the finished keg from the re-ferment.

Cheers for your work legends.

If I’m reading a carb chart right, 22psi and 40f give you about 3.4psi, a little over your target but pretty close. I’ve read articles about estimating the gas already in solution based on fermentation temperatures and then calculating how much sugar to reach your target; did you use one of these methods or just add a certain amount of volumes? Also, did you anecdotally notice more or less trub in the first few pours from the natural carb?

Cool xBmt, something I’ve been pondering doing myself.

“Understanding that re-fermentation in a keg results in some scrubbing of oxygen, I have concerns about leaving beer at warmer temperatures for too long, especially lighter and dry hopped styles.”

I’m confused by this sentence. As written, it seems like you’re suggesting that the O2 scrubbing benefit of natural carbonation is a bad thing. If we assume that the yeast will consume any O2 picked up during transfer, then it stands to reason that the beer could sit at the warmer temps for several days without any oxidative effects. I wouldn’t leave it warm for a month, but 7-10 days of re-fermentation in the keg shouldn’t be an issue.

I wouldn’t expect there to be discernible taste difference between these two methods; dissolved CO2 is dissolved CO2. The benefits are the O2 scrubbing and the fact that you’re getting 100% pure CO2 in your beer, this extensing shelf life and preserving freshness. I wish I had the knowledge and lab equipment to prove that it works like that, but it does make sense.

Just listened to the pod today. Thoughts on carbonating with a stone in the keg instead of just on the intake post? I just did this with a .2 micron stone for a hard seltzer and the head and carbonation is definitely different. Going to try it on a Tripel I’ve been working on to get a head like Staminee de Garre (https://www.degarre.be/nl/tripel-de-garre).