Author: Phil Rusher

Consisting of a primarily Pilsner malt grist, noble hops, and a clean fermenting lager yeast, German Pilsner is known for being delicate and clean, offering little for undesirable flavors to hide behind. In producing this delectable style, many brewers employ various methods to ensure a successful outcome, one of which involves reducing the amount of kettle trub that makes its way to the fermenter. Made up mostly of proteins, fatty acids, and hop debris, trub is believed by many to negatively impact beer flavor, mouthfeel, and head retention.

Out of the three previous xBmts we’ve performed on this variable, the results from two have suggested higher amounts of kettle trub present during fermentation produced no perceptible differences in a Cream Ale or Vienna Lager, while tasters were able to tell apart a German Pilsner fermented with little trub from one fermented with a lot of trub after 5 weeks of aging. What was consistently observed in all past kettle trub xBmts is that higher amounts in the fermenter led to reduced lag, more vigorous fermentation, quicker attenuation, and better clarity in the finished beer, all arguably positive.

While I’ve never been one to dump every last bit of kettle trub into my fermenter, I’ve also not worried too much about the impact it might have on the quality of my beer, which is admittedly influenced by the previously mentioned xBmt results. Unable to gather data due to the COVID-19 quarantine, I decided to take this opportunity to see if I might be able to tell a difference in German Pilsners brewed with varying amounts of kettle trub.

| PURPOSE |

To evaluate the differences between a German Pils fermented with minimal kettle trub from one fermented with a high amount of kettle trub.

| METHODS |

For this xBmt, I went with a pretty typical German Pilsner recipe that I’ve always enjoyed having on tap.

Proper Pronunciation

Recipe Details

| Batch Size | Boil Time | IBU | SRM | Est. OG | Est. FG | ABV |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5.5 gal | 60 min | 29.3 IBUs | 3.6 SRM | 1.049 | 1.012 | 4.9 % |

| Actuals | 1.049 | 1.01 | 5.1 % | |||

Fermentables

| Name | Amount | % |

|---|---|---|

| Belgian Pilsner Malt (MFB) | 10 lbs | 98.77 |

| Swaen©Melany | 2 oz | 1.23 |

Hops

| Name | Amount | Time | Use | Form | Alpha % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hallertau Magnum | 15 g | 60 min | Boil | Pellet | 11 |

| Hallertauer Mittelfrueh | 15 g | 20 min | Boil | Pellet | 3.7 |

| Hallertauer Mittelfrueh | 25 g | 10 min | Boil | Pellet | 3.7 |

| Tettnang (Tettnang Tettnager) | 35 g | 1 min | Boil | Pellet | 3.9 |

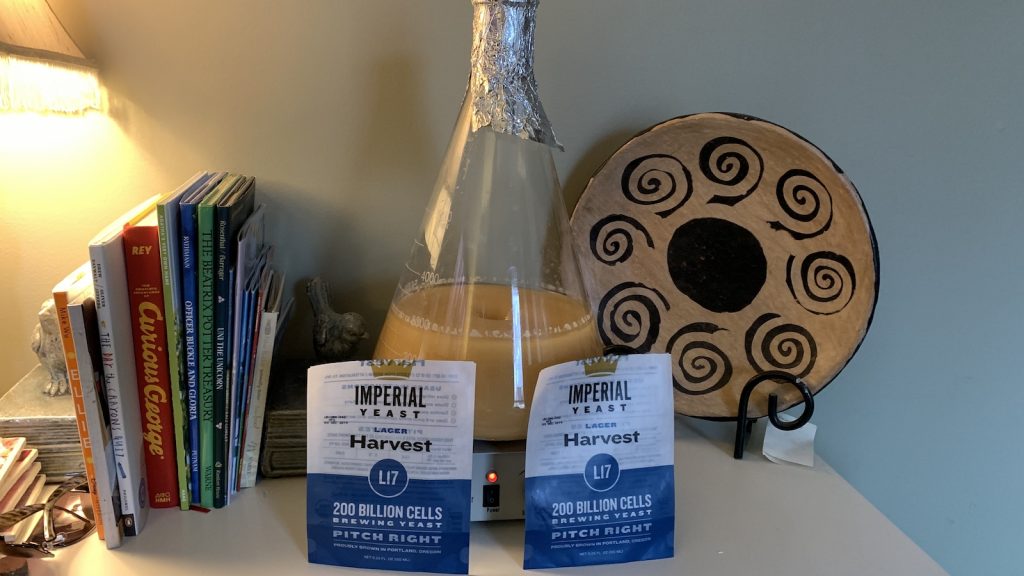

Yeast

| Name | Lab | Attenuation | Temperature |

|---|---|---|---|

| Harvest (L17) | Imperial Yeast | 72% | 50°F - 60°F |

Notes

| Water Profile: Ca 50 | Mg 10 | Na 5 | SO4 105 | Cl 45 |

Download

| Download this recipe's BeerXML file |

I made a single large yeast starter of Imperial Yeast L17 Harvest a couple days ahead of time.

On the morning of brew day, I weighed out and milled two identical sets of grain.

I then collected the water for both batches, adjusting each to my desired profile before heating them to the same strike temperature, at which point I stirred in the grains and checked to make sure both hit the same mash temperature.

After setting each controller to maintain the same mash temperature, I weighed out the kettle hop additions.

When each 60 minute mash rest was complete, I removed the grain baskets and let them drip into their respective kettle while heating the wort.

With the full volume of sweet wort collected, I boiled each batch for 60 minutes, adding hops at the times stated in the recipe.

When the boil for each batch was completed, I recirculated each wort through a plate chiller until they reached the same temperature. At this point, I propped a piece of wood under the front of the kettle holding the low trub wort and let it sit for 20 minutes to allow all of the trub to settle to the bottom before gently racking it to a fermenter. The high trub wort was immediately transferred to a fermenter once chilled, suspended trub and all.

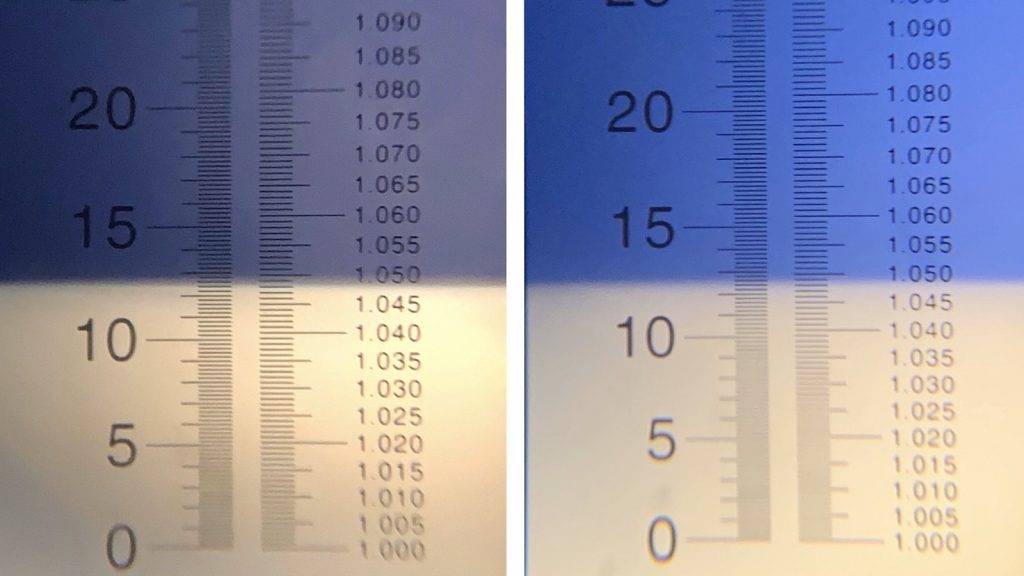

Refractometer readings showed the worts were at the same OG.

The filled fermenters were placed in my chamber controlled to my desired fermentation temperature of 51°F/11°C and left to finish chilling for a few hours. The difference in trub amount was quite drastic.

Once the worts were chilled, I split the yeast starter evenly between them. When I came back the following day, both beers were showing signs of similar activity, an observation that counters past xBmts on kettle trub.

After a week of fermentation, I raised the temperature to 65˚F/18˚C and left them alone a few more days before taking hydrometer measurements showing both finished at the a very similar terminal gravity.

The beers were then racked to sanitized and CO2 purged kegs.

The filled kegs were placed in my keezer, burst carbonated, and left to condition for 3 weeks before being evaluated, at which point a noticeable difference in clarity was observed.

| RESULTS |

Due to social distancing practices as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic, data for this xBmt was unable to be collected in our typical manner. As such, temporary adaptations were made involving the author completing multiple semi-blind triangle tests in as unbiased a way as possible.

Utilizing 4 opaque cups of the same color where 2 were inconspicuously marked, one set was filled with the beer made with a small amount of kettle trub while the other set was filled with the beer made with a large amount of kettle trub. For each triangle test, 3 of the 4 cups were indiscriminately selected, thus randomizing which beer was the unique sample for each trial. Following each attempt, I noted whether I was correct in identifying the unique sample. Out of the 10 semi-blind triangle tests I completed, I needed to identify the unique sample 7 times (p<0.02) in order to reach statistical significance. However, I was able to correctly identify the unique sample 8 times (p=0.003), indicating my ability to reliably distinguish a German Pilsner fermented with large a large amount of kettle trub from one fermented with a minimal amount of kettle trub.

Despite perceiving a difference between these beers, I relished both of them! They were crisp and easy to finish quickly, even when a 500 mL stein was the serving glass of choice. The key difference to my palate came in the finish– I perceived the low trub beer as being more dry and crisp, whereas the beer fermented with a lot of trub was sweeter, and dare I say, had a touch more “flubber” character to it. I preferred the low trub beer, but certainly wouldn’t turn away a pint of the high trub version.

| DISCUSSION |

Perspectives on the impact kettle trub has on beer vary among brewers, with some doing everything possible to rack only the clearest to the fermenter while others rack over the entire contents of their brew kettle. Observations from past xBmts on the subject suggest higher amounts of kettle trub can influence fermentation vigor and final beer clarity, though only when a pale lager was aged for a bit in primary did kettle trub seem to have a perceptible effect. Despite my slight skepticism going into this xBmt, I was able to reliably distinguish a beer fermented with minimal kettle trub from fermented with a high amount of kettle trub, indicating it did have a noticeable impact.

Similar to all past xBmts on this variable, the beer fermented with a lot of kettle trub ended up being clearer than the one fermented with less trub; however, no differences were observed in lag or fermentation activity between the batches, which may speak to the health of the yeast that was pitched. Additionally, the low trub beer finished 0.001 SG point lower than the high trub beer, which was unexpected given the outcome of past xBmts.

One plausible explanation for these results is that there may be diminishing returns when it comes to the amount of kettle trub present during fermentation, a point at which the impact on beer character outweighs the fermentation and clarity benefits. It’s also possible simpler pale styles of beer offer little for the perceptible influence of kettle trub to hide behind. Personally, I appreciate the observable affect fermenting with kettle trub has and will continue to allow a small amount to transfer into the fermenter with the wort, though I’ll certainly be cautious not to add too much in hopes of avoiding any undesirable flavor development.

If you have any thoughts about this xBmt, please do not hesitate to share in the comments section below!

Support Brülosophy In Style!

All designs are available in various colors and sizes on Amazon!

Follow Brülosophy on:

FACEBOOK | TWITTER | INSTAGRAM

If you enjoy this stuff and feel compelled to support Brulosophy.com, please check out the Support page for details on how you can very easily do so. Thanks!

17 thoughts on “exBEERiment | Kettle Trub: Low Vs. High In A German Pils”

I think that the main takeup here is in the spirit of Charlie Papazian: relax, don’t worry.

On one hand, I would submit that, yes, let your wort clear before racking to the fermentation vessel, but don’t worry about a bit, or even 1/10 or 1/4 of the trub in your vessel.

On the other hand, all the results of the trub experiments seems to be countering to all these homebrewers who like to reference big names that say that your wort must be as clear as possible. The experiment bears out that this is not really necessary.

I think that especially the reference to Künze, where he submits that excess trub is detrimental to the yeast, should be put to rest. These experiments actually show the reverse.

Im not here to start a fight, but you can’t argue with the fact that cloudy wort transfers contain increased levels of compounds which will advance staling past N’s Stage A and into Stage B & C faster. It may be, that you can drink a beer 3 weeks young and not yet taste Stage B flavors, but advocating for high trub and cloudy transfers flies in the face of wort analysis science and best brewing practices.

Sorry, it might have been Dalgliesch’s 3 beer staling stages and not Narziss I was thinking of.

At any rate, brew beer your own way.

Cheers,

There are lots of things that are supported by the science and certainly applicable to commercial breweries. But homebrewers have found that so much of that science simply doesn’t matter at the homebrew level.

This website has proven that (as best as can be proven at this level)

so many times.

I think that if you have to preface something with “I’m not here to start a fight” then you probably know that you are about to stir up controversy!

But I hear what you’re saying, and you’re right. Lipid oxidation through kettle trub is a real concern for beer production. However, unless trub levels are excessive, most of the lipids present in a small amount of kettle trub will be fully utilized for synthesis of budding yeast.

Also, I don’t think anyone here is advocating for high trub transfers. Just sayin’.

Good to know that this is pretty much an “either or” deal. When I first started brewing, I would painstakingly rack the wort into the fermenter, attempting to keep everything but liquid out. After a few years, I started to look at it as another piece of equipment to clean and another potential to introduce an infection so I stopped. As of now, I just dump it all in the fermenter. It gives me a head start on oxygenation and less to clean. However, as I get older, it gets a bit harder to pickup a boil kettle with ~6 gallons of wort so I may be heading back to racking. Pool or pond.

Thanks for doing this one, Phil. Much appreciated.

Great experiment – as usual! But a question: Can you please describe the “flubber” character a bit more? I am not a native English speaker and “flubber” doesn’t really mean anything to me. Googling didn’t help either… Thanks!

I am a native English speaker, and I also have no idea what “flubber” means! Please explain!

Ha! The flubber descriptor was just a callback to what Marshall described in his beer. For me, it meant that the high trub beer was simply a bit sweeter and softer on the palate. It’s not a real beer descriptor outside of this blog 🙂 (but we can change that!!)

I appreciate this one. It’s something I’ve been wanting to do myself, but haven’t got around to it. I made a Maibock last a while ago that was fine, just a little weird & lacking crispness. I think “flubber” fits. I transferred quite a bit of trub to the fermenter (a plastic carboy) & let it sit on the yeast for 3 weeks. My guess has always been oxidized trub or something.

> My guess has always been oxidized trub or something.

Yeah, maybe. In my experience though, plastic FVs tend to be markedly more permeable to oxygen, so that would be my first suspect in the culprit of cold side oxidation. It’d be worth a redo for you in stainless vessel, maybe.

Definitely appreciate this experiment. I’ve said it before and I’ll say it again…I’m a Super Truber. 🙂 Stovetop BIAB, dump the entire kettle through a funnel into the carboy, and never move the beer off the trub into a secondary.

Glad to see yet another confirmation around clarity of the high trub beer. But I’m also interested in what this “flubber” character or taste is…wondering if it is impactful enough for me to rethink any of my methods!

I have been reading a lot on whirlpooling. This experiment kind of goes against whirlpooling. Is whirlpooling worth it? DO you guys whirlpool?

I wouldn’t say that whirlpooling isn’t worth it, and I definitely wouldn’t say that this experiment goes against that. Whether or not I whirlpool really depends on what sort of gear I’m using. For instance, I do not whirlpool with these Clawhammer setups but I do with others. I will often let trub settle to the bottom of the boil kettle no matter what, though. Do I always strive for crystal clear wort? Nah.

W.r.t. to whirlpooling, I think that it works better in larger vessels. It definitely does not work for me with less than 10l. I think that 20l (5-5.5gal) is on the brink, and that whirlpooling only really starts to working above that volume.

I think it might depend more on the radio of volume of trub and hop material to wort. But you’re probably right in that larger vessels will make the process more effective in general.

I know I’m a little late to the game on this one being a few years old, but I think I can shine a light on some of these findings.

I came across this one in my search since this was a recent debate in our brew club meeting.

Professionally I am a water treatment consultant for industrial plants and work with clarifying water on a daily basis. A piece of equipment called a clarifier is used. We add in a coagulant (whirl floc is a coagulant) to the inlet water and a major part of the clarifier is maintaining a sludge (trub) layer that the water passes through. This sludge acts as a filter and nucleation points for the water to clarify. Impurities in the water then become part of the sludge. This is most likely what the trub is doing in that it gives nucleation points for the proteins to agglomerate with and fall out of solution.

Hope this makes sense! My work and my hobby definitely overlap.