Author: Jake Huolihan

Shelf stability of finished beer is perhaps the single most invested in issue in modern brewing. While brewers have known for centuries how to create a tasty beverage, making sure it retains its delicious properties over time has been a struggle shared by many. As distribution of beer increased, a number of methods were developed to ensure the consumer receives the highest quality product that’s as close as possible to what the brewer intended.

Modern advancements such as aluminum cans and oxygen purging machines have all played a role in the ability for one to enjoy a beer in Colorado that was brewed in Florida, Great Britain, or even Japan. Unfortunately, such technologies tend to be quite expensive and cumbersome, putting them out of reach of smaller breweries and homebrewers. However, oxygen scavenging chemicals such as sulfites are both cheap and easily accessible, offering a novel method for filling this technological gap.

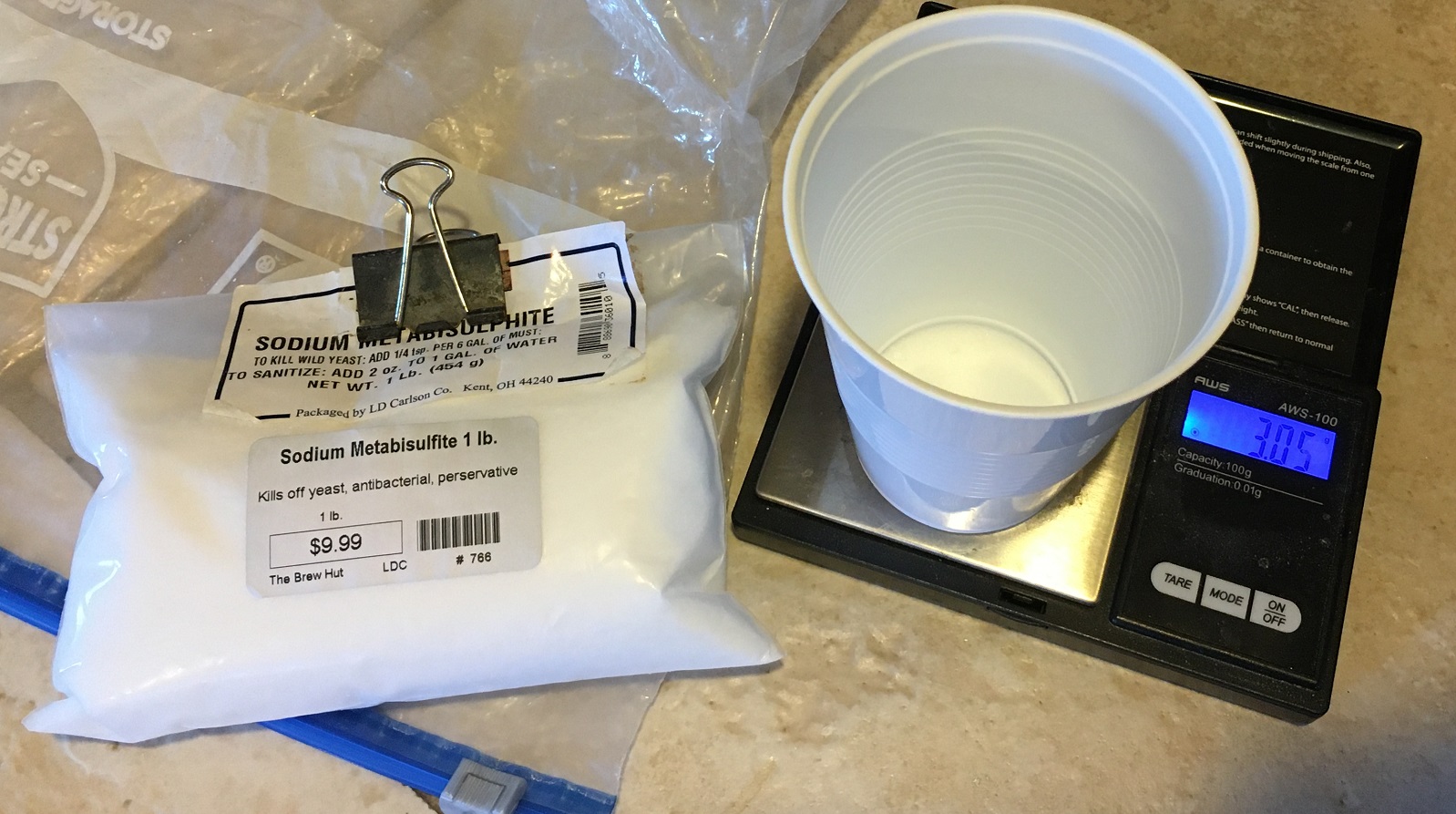

I’ve been using sodium metabisulfite (SMB) when packaging my beer for well over a year now, it’s become a regular part of my process as I’ve found the results to be quite positive. However, some have argued the addition of sulfites can create undesirable off-flavors, namely sulfur, though I’ve personally never experienced this. Curious if the amount of SMB used has an impact on beer character, I tested it out for myself.

| PURPOSE |

To evaluate the differences between a beer dosed with either 10 ppm or 100 ppm of SMB at packaging.

| METHODS |

I went with a hoppy Pale Lager for this xBmt in hopes of emphasizing any differences caused by the variable.

Baskin Buffet

Recipe Details

| Batch Size | Boil Time | IBU | SRM | Est. OG | Est. FG | ABV |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5.5 gal | 60 min | 55.1 IBUs | 4.4 SRM | 1.045 | 1.011 | 4.4 % |

| Actuals | 1.045 | 1.009 | 4.7 % | |||

Fermentables

| Name | Amount | % |

|---|---|---|

| Odyssey Pilsner | 10.75 lbs | 97.73 |

| Melanoidin (Weyermann) | 4 oz | 2.27 |

Hops

| Name | Amount | Time | Use | Form | Alpha % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Magnum | 20 g | 60 min | Boil | Pellet | 12.2 |

| Sabro | 25 g | 10 min | Boil | Pellet | 14 |

| Bru-1 | 12 g | 10 min | Boil | Pellet | 13 |

| Eukanot | 10 g | 0 min | Boil | Pellet | 14 |

| Bru-1 | 15 g | 3 days | Dry Hop | Pellet | 13 |

| Sabro | 15 g | 3 days | Dry Hop | Pellet | 14 |

Yeast

| Name | Lab | Attenuation | Temperature |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cablecar (L05) | Imperial Yeast | 73% | 55°F - 65°F |

Notes

| Water Profile: Ca 49 | Mg 0 | Na 8 | SO4 38 | Cl 61 |

Download

| Download this recipe's BeerXML file |

A day prior to brewing, I prepared a starter of Imperial Yeast L05 Cablecar.

After collecting the water, adjusting it to my desired profile, and setting my controller to heat it up, I weighed out and milled the grains.

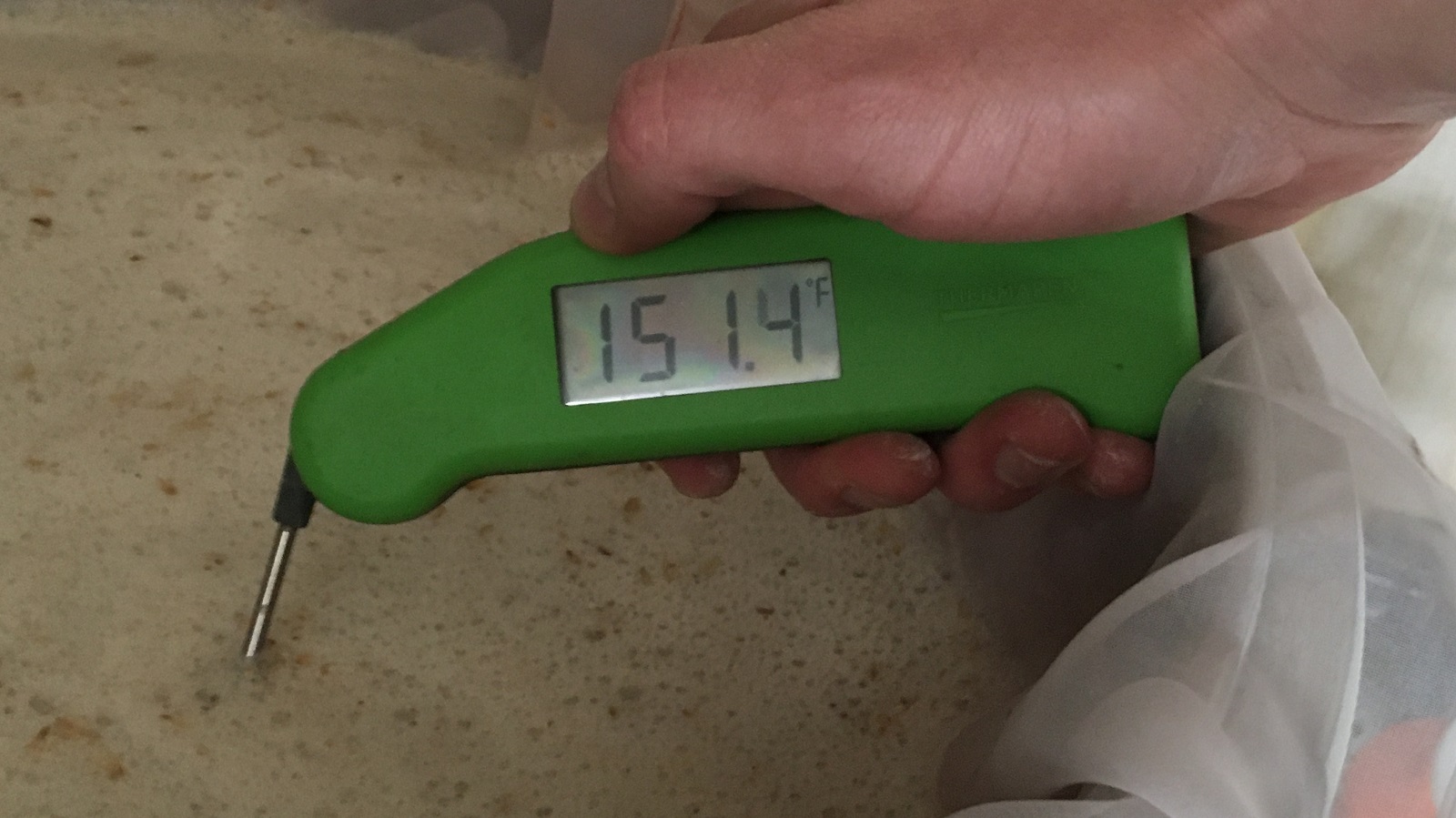

With the water appropriately heated, I stirred in the grist then checked to ensure it was at my target mash temperature.

The mash was left to rest for 60 minutes with intermittent stirring.

With the mash rest complete, I transferred the sweet wort from the MLT to the kettle.

While lautering, I weighed out the kettle hop additions.

The wort was then boiled for 60 minutes with hops added as stated in the recipe.

Once the boil was complete, I quickly chilled the wort.

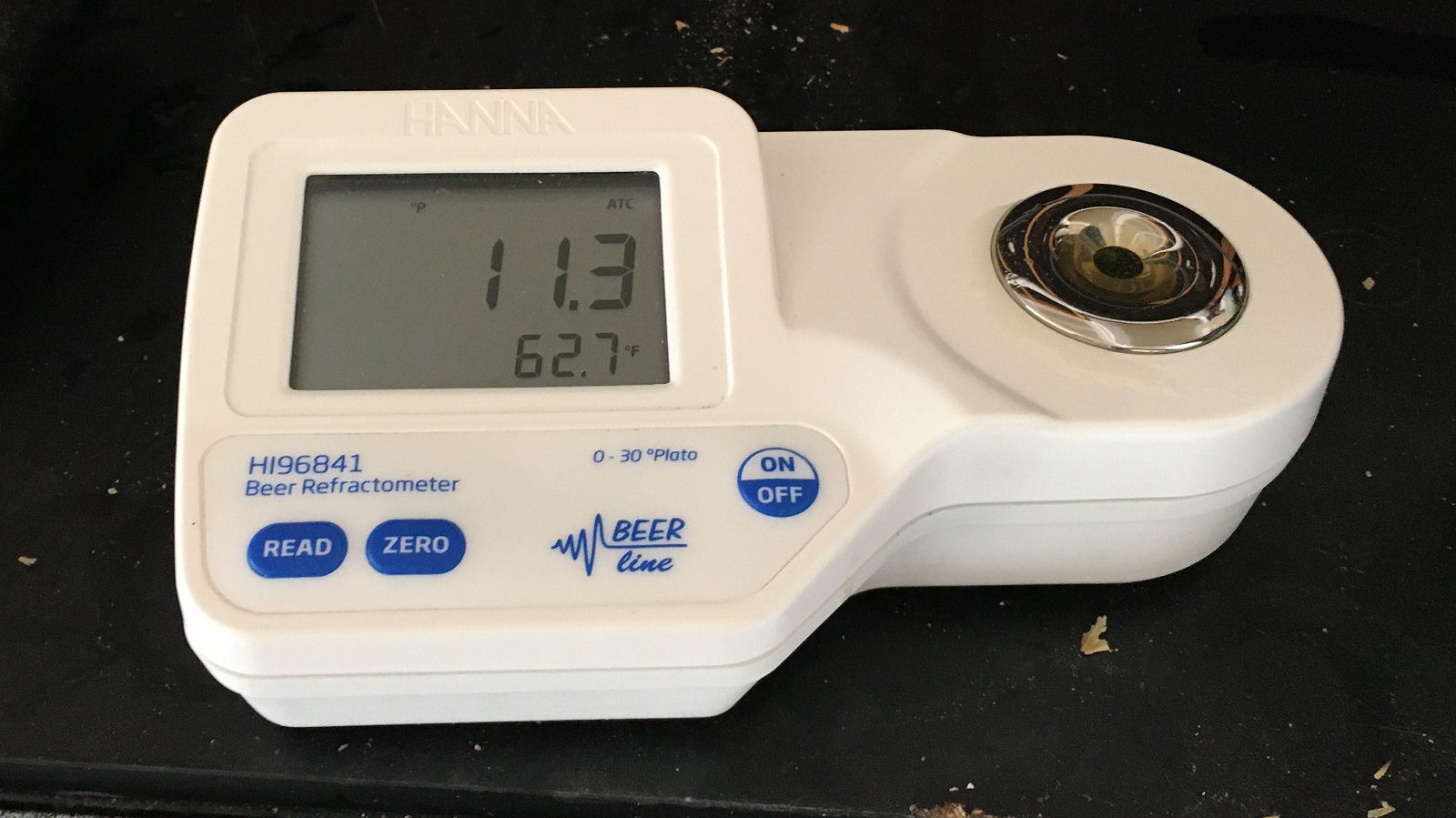

A refractometer reading showed the wort was right at my planned OG.

Identical volumes of wort were racked to separate sanitized Ss Brewtech Unitanks that were connected to my glycol rig and left to finish chilling to my desired fermentation temperature of 56°F/13°C before I split the yeast starter between them.

As fermentation activity was winding down, I capped the vessels to allow a small amount of pressure to build up then chilled them to 40°F/4°C. I let the beers lager for 8 weeks before taking hydrometer measurements confirming both finished at the same 1.009 FG. At this point, I prepared for packaging by adding 3.0 grams of SMB to one sanitized keg while the other received 0.3 grams, the amount I typically use.

At this point, I proceeded with racking each beer under pressure to sanitized and purged kegs.

The filled kegs placed next to each other in my keezer and burst carbonated overnight before I reduced the gas to serving pressure. About 24 hours after kegging, I eagerly pulled samples of each beer for comparison and noticed the one dosed with less SMB appeared slightly darker.

A couple weeks later, the beers were equally carbonated and ready to drink. While subtle, I continued to observe a difference in appearance, with the beer dosed with more SMB maintaining a slightly paler color.

| RESULTS |

Due to social distancing practices as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic, data for this xBmt was unable to be collected in our typical manner. As such, temporary adaptations were made involving the author completing multiple semi-blind triangle tests in as unbiased a way as possible.

Prior to the quarantine, 10 people of varying levels of experience participated in this xBmt at Honnibrook Meadery. Each participant was served 2 samples of the beer dosed with 3.0 grams of SMB at packaging and 1 sample of the beer dosed with 0.3 grams of SMB at packaging in different colored opaque cups then asked to identify the unique sample. While 7 tasters (p<0.05) would have had to accurately identify the unique sample in order to reach statistical significance, only 3 (p=0.44) did, indicating participants in this xBmt were unable to reliably distinguish a beers dosed with SMB at packaging to either 100 ppm or 10 ppm.

Utilizing 4 opaque cups of the same color where 2 were inconspicuously marked, one set was filled with the beer dosed with 3.0 grams of SMB (100 ppm) at packaging while the other set was filled with the beer dosed with 0.3 grams of SMB (10 ppm) at packaging. For each triangle test, 3 of the 4 cups were indiscriminately selected, thus randomizing which beer was the unique sample for each trial. Following each triangle test attempt, I noted whether I was correct in identifying the unique sample. Out of the 10 semi-blind triangle tests I completed, I needed to identify the unique sample 7 times (p<0.05) in order to reach statistical significance, though I did so just 4 times (p=0.44), indicating my inability to reliably distinguish a beer dosed with 3.0 grams of SMB at packaging from one dosed with 0.3 grams.

As a lover of the hoppy Pilsner, these beers definitely lived up to my expectations. I perceived a pleasant piña colada flavor, particularly as the beer warmed, which I believe was due to blend of Sabro and BRU-1 hops. This being my first time using Ekuanot Incognito, I was very pleased with how it seemed to enhance the fruit character while also adding a nice resinous note that I found insanely pleasant. I look forward to brewing with this hop combo in the future and cannot wait to get my hands on some more Incognito for use at flameout!

| DISCUSSION |

Among its various uses, sodium metabisulfite (SMB) is a known antioxidant that, once dissolved in a liquid such as beer, goes through a redox reaction wherein sulfite ions bind with oxygen in solution, thus reducing the risk of oxidation. Typically for such usage, enough SMB is used to impart the beer with approximately 10 ppm of sulfite at packaging, and some have claimed higher rates can lead to undesirable off-flavors. However, I was unable reliably distinguish a beer dosed with 10 times the normal amount of SMB from one dosed with a standard amount.

I may not have been able to tell these beers apart based on aroma, flavor, or mouthfeel, but the increased SMB clearly had some impact based on the observed difference in color post-packaging. Personally, this was quite interesting to me, as it corresponds with findings from a previous xBmt on the impact of SMB at packaging. While these beers were identical to my palate despite the color difference, it seems plausible the lower dosed version might stale before than the one dosed with more SMB if left alone even longer.

Based on my experience with this xBmt, I now feel more comfortable using higher amounts of SMB at packaging without fear of my beer developing a sulfur off-flavor. To me, this method is an easy and affordable way to reduce the risk of beer being ruined by cold-side oxidation. For the brewer interested in trying this out, I would recommend starting with a lower dose and experimenting from there, as it’s possible different systems will yield different results.

If you have any thoughts about this xBmt, please do not hesitate to share in the comments section below!

Support Brülosophy In Style!

All designs are available in various colors and sizes on Amazon!

Follow Brülosophy on:

FACEBOOK | TWITTER | INSTAGRAM

If you enjoy this stuff and feel compelled to support Brulosophy.com, please check out the Support page for details on how you can very easily do so. Thanks!

41 thoughts on “exBEERiment | Impact Higher Dosage Rates Of Sodium Metabisulfite (SMB) Have On German Pils”

Could this be a partial explanation for the lighter color of the higher dosed beer?

Sodium Metabisulfite in food has anti-browning effects. … 0.0001% of sulfur dioxide can reduce 20% of the enzyme activity, 0.001% of sulfur dioxide can completely inhibit the enzyme activity and can prevent enzymatic browning; In addition, can consume oxygen in food organization and has deoxidation effect.

I would be surprised if the explanation was anything other than the anti-ox effects of the sulfite.

I added SMB to hoppy blond recently and loved the results beer seemed fresher for longer but man i dont know if im getting weak or if its a correlation to adding SMB at packaging but my hangovers have been intense.

Anyone else get this…?

I love a big red dry wine but as I got older I started getting bad headaches after one or two glasses. I have been told that it is most likely from the metabisulfite in the wine. I use to make wine before I got into brewing and always measured my meta additions in as small amounts as I could and still safeguard the wine. I actually used potassium metabisulfite instead of sodium metabisulfite. Hope this helps stay safe and healthy.

I get crazy hangovers when I drink a lot of ethanol

SMB gives me a headache for sure. I use to make wine and I still love a big red but I guess over time I’ve become more sensitive to it. One glass can give me a hell of a headache.

The amount of sulfite we’re talking about using is a fraction of what you’ll find in wine. Idk, no one is forcing you to use it, I’ve found it to be very useful at preserving flavor without any adverse impacts

I didn’t say anyone was forcing me to do anything, just giving my observation with the experience I have with meta. When I made wine I actually used Potassium metabisulfite. I found it to be softer.

When corrected they both contribute the same amount of sulfite. If sulfite is the issue it’s not actually softer, it’s just slightly less by weight

Nice Jake! Now that you have used this process for quite awhile now, I have a curious question as I have tried this a couple of times myself. Assuming you are purging the kegs with CO2 only once the SMB is added, do you think the benefit of adding SMB is worth opening up an already purged keg? This xbmt might have shown that opening the keg to add a small amount of SMB still exposes the beer to O2. What is your purge process after SMB? Or do you have a way to add SMB without open the purge keg? Maybe there is a way to add a SMB solution to the beer just prior to racking? Or through the beer line?

There are definitely ways to add the sulfite solution in a more o2-less way I simply am not willing to go through the effort since it works so well. Typically I’ll start my racking process, crack the lid and gently add the solution, blast a little co2 in there and then close it.

If adding gelatin finings, would you see any problem with adding the SMB at the same time, to at least limit the number of O2 exposures?

I do that with wine every time!

My way of dosing SMB in a corny is to purge the keg and prepare for a closed transfer. I make up a solution of SMB in a 20ml syringe. I vent the keg from excess CO2 with the pressure relief valve, and as the keg approaches atmospheric pressure, I unscrew the valve, squirt the solution in, and screw the valve back in. Then do the closed transfer.

I do something similar although I use a 100ml syringe to add flavourings gelatin etc. I use a very short length of silicone tubing and an MFL hose barb to a grey gas connector. leave 2-3 psi in. Fill the syringe only half way (maybe does twice for gelatin)

Remove all air from the syringe then connect it all making sure that I have my thumb firmly over the plunger. Then allow the pressure to push the gas from the tubing into syringe (to help purge the o2 in the tubing). Then push the fluid in leaving just a small amount of fluid then pull off the disconnect. Pretty much 02 free and pretty easy. Just keep your thumb over the plunger! A mistake you want only make once!

I’ve always just cracked the lid while kegging and dumped it in. It’s not a very good process but every time I’ve done it the color is different.i need to find a way to test this now that you’ve got me thinking

While sulfites are allowed in many foods, beverages, cosmetics, etc. some people may have an adverse reaction. I’m not sure of the dosage in commercial products as compared to the experiment.

Another point as to the different color between the lower dosage and higher dosage of SMB, sulfites are used in food preparations to prevent browning. Sulfites have a bleaching effect on the foods and drinks where they are used. See the link for details. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4017440/

Thanks for sharing I’ll need to check on bleaching effect versus stalling oxidation for sure!

Just an FYI, twice I added campden tablets to beers I was bottle conditioning and dissolved it right right into my bottling bucket with the beer and then bottled and the beers were basically all undrinkable even after months because of a potent sulphur flavor and aroma, I’ve had other people who bottle condition note this as well. That being said I never have had an issue when I add it into a keg, even at higher doses. My thought is the bottles don’t allow the spulfur to dissolve out of the beer, but that being said neither would a full keg necessarily. I only use it when kegging now, bottle conditioned beer is low risk anyway because the yeast will just reabsorb the oxygen.

Be a cool xBmt imo

It seemes you guys had a similar issue when doing your low hot side DO experiment when sulfite was added to the mash and then you had a sulphur bomb. Seems the quote from Charlie Bamforth saying the yeast converts the sulfites to sulfides might be the issue here. So when bottle conditioning like I did you get sulphur smell/taste the same thing occurs and this wouldn’t be an issue if you keg and the yeast is inactive. This mechanism seems plausible and worth knowing for people who might extrapolate these results to their bottle conditioned beer.

As far as I know adding SMB to beer on packaging will only work with kegging, not for bottle conditioning. SMB is primarily used as a sanitiser, and if added to bee before or at bottling will kill the yeast. So apart from sulphite off flavours there will be little or no carbonation. I use SMB exclusively for sanitising my bottles and brewing equipment.

My experience with this is that meta will kill wild yeast and bacteria but not a domesticated or cultured yeast as long as the doses are limited. To stop fermentation in wine you use sodium sorbate. Now I’m not at all sure how meta affects brewer’s yeast vs wine yeast. When I was ready to bottle the wine I did as you do, rinse clean bottles in a meta solution, drain, dry, then fill.

Could I use meta to give more stability and shell life to my beer?

Actually in both the instances that I mentioned above the beers carbonated in the bottle just fine. It’s my understanding you would have to at so much SMB/PMB the beer would be completely undrinkable to actually kill your yeast, much higher than the doses mentioned here.

We’re not using close to levels that would prevent bottle carb tho

I add SMB and ascorbic acid when I bottle, 0.25 g and 3 g respectively for a 5 gal batch. At that low level bottle conditioning doesn’t seem to be affected at all, and I still get substantially improved shelf life and retention of hop aroma.

Sodium metabisulfite is not something that should be used. Having being diagnosed as allergic to this it can send people into anaphylaxis, it is added to too many products so the amount a person is taking in a day is unknown and look at what it was used for years ago!!! Just to keep your beer longer

If the sulfite, which becomes sulfur dioxide, is eaten by oxygen what is causing the reaction? I’m not trying to say you don’t have a legit

Allergy, just saying if you’re using this compound in a thoughtful way there is not any sulfur left when you drink it

Thanks for the heads up. I really need to sharpen up my labelling as I start to get more creative with ingredients and share more. Especially given I only share with people I like .

Good work and very interesting. I recently read “COLD-SIDE OXIDATION: IMPACT OF DOSING BEER WITH POTASSIUM METABISULFITE (PMB) AT PACKAGING | EXBEERIMENT RESULTS!” report written by Cade Jobe. After reading that I bought some PMB for use in my processing. I don’t have much experience using either SMB or PMB. Do you think this exbeeriment can also be relevant to the use of PMB?

I think it probably can be

Yep. But slightly different dose rates.

Great stuff! As for the protocol, you write that you checked each time whether you were correct; that can introduce some added knowledge of the variable, in that in these 10 trials, one could learn to discriminate the two beers. It’d seem more fair (or at least, closer to the older format) if someone else was to check the results each time, or if the results were checked after the 10 attempts (by saving the cups for instance). Cheers!

No, every test was an equalized volume of 4 beers randomized. I will then grab 3 and t test myself, this way I have no clue which is the odd one out. It’s time intensive but a very good learning tool

Except that you are educating your pallet over time. I actually think that is a bit better. Sometimes it takes me a couple of sessions with a beer to really understand it. At which point I think I could make better judgements about minor variations.

Did this exact thing by accident with an Oberon Clone. I chocked down one pint and almost immediately had a raging headache. Dumped the rest.

I think there might be a small error. For the independent tests (pre-quarantine) you said that there were 10 people and only 3 guessed for p=0.44.

When you did your semi-blind tests, you did it 10 times and guessed correctly 4 times but listed the same p=0.44,

I’ve always been bad at statistics but i think those p-values should be different.

What is the proposed chemical reaction?

Hey guys, I’ve been experimenting with Sodium Metabisulfite (SMB) and I’m convinced it’s the cheapest insurance against oxidation of hoppy beers. I read a lot of people using way too much of this stuff and complain about sulfur odors and poor fermentation so I wanted to share my method for precisely dosing it. I hope you’ll appreciate the beauty of the metric system:)

My goal is to have 10 ppm of SMB in the beer prior to bottling/kegging. I make a stock solution by mixing 100 ml of cold water with 1 gram of SMB in a sanitized jar. This gives me a concentration of 10 mg per ml of solution. For each liter of beer I measure 1 ml of stock solution with a syringe, so for example if I’m going to package 14 liters of beer I will add 14 ml of this solution to the receiving keg (I attach the syringe to a quick disconnect) or bottling bucket.

You will need an accurate scale (something like 0.01 g resolution is ideal). If your scale is precise to 1 g you have to make 1 liter of stock solution with 10 g of SMB, which ist still dirt cheap.

Question to the brulosophy crew: do you happen to know how long the SMB solution will be good for? I know that SO2 will form in an acidic solution and come out of solution over time, but I couldn’t find anything on the stability of metabisulfite in neutral/basic solution.

I’ve got a diagnosed sulphite allergy. It results in a tightening and pain in the throat and can lead to choking. I thought I’d share a few experiences which might form a basis for future experiments and help people decide how or if to use sulphites.

My experience has been very low levels of sulphites can cause an allergic reaction. For example, yeast strains produce various levels of sulphites. When I recently brewed using lachancea I got an allergic reaction. I read some wine making journals on lachancea and found it produced relatively high levels of sulphites in some testing at 55ppm. Given food regulations around the world require commercial operators to label over 10ppm added, due to allergic reactions, yeast production alone can set off allergies. My take away is your end product may end up with significantly more sulphites than you intend if you’re adding them on top and have not tested base levels. That’s pretty dangerous for anyone with an allergy who might happen to drink your beer.

The other consideration is the likelihood of someone with an allergy coming into contact with your beer. There is a link between asthma and sulphite allergy. About 5-10% of asthmatics seem to develop it (https://www.allergy.org.au/patients/other-allergy/sulfide-allergy). The rates of asthma in the community varies by country. In Australia where there is affordable health care the diagnosed rate sits at around 11% of the population. Putting those two numbers together, up to 1 in 100 people potentially have a sulphite allergy.

I get an allergic reaction to a lot of craft beer (which drives me crazy because I live in a suburb known for its craft beer, there are literally 10 breweries in walking distance). None of them label that they add sulphites, my working thesis is that their yeast strains are high producers or that they are using it in cleaning.

So overall is urge caution on their use, especially if you aren’t testing the sulphite levels your yeast is producing and if you don’t know what allergies people might have that are drinking your beer.