Author: Matt Del Fiacco

In brewing, there are various decisions one makes that are said to have a noticeable impact on the final beer, levers that can be adjusted by the brewer to produce a predictable outcome. One such example is mash temperature. As a function of enzymatic activity, a beer mashed at a lower temperature will experience higher attenuation and thus finish at a lower specific gravity (SG) than one mashed warmer. Seeing as yeast metabolize sugar during fermentation, the idea that mash temperature can be used to adjust the perceptible sweetness of beer makes practical sense.

Curiously, the results of multiple past xBmts on mash temperature have failed to uphold this notion. Despite the differences in attenuation and level of alcohol, tasters have generally been unable to tell apart beers mashed at different temperatures. While surprising to many, one possible explanation for those results is that the beers brewed in each xBmt were pale, clean, low OG styles. It’s been suggested that mash temperature might have more of an impact on a higher OG beer fermented with a characterful Belgian yeast strain.

For me, the mash temperature xBmts have been some of the most shocking. This is due to both the frequent insistence that even small differences in mash temperature matter as well as the myriad papers out there discussing the chemical impacts of mash temperature. Given the objectively observable results from past xBmts, clearly it has an impact, but the fact it wasn’t perceptible had me scratching my head. Like others, I began to wonder if the prior inconclusive results might be due to the beer style and put it to the test with a big Belgian ale.

| PURPOSE |

To evaluate the differences between Belgian Ales mashed at either 148°F/64°C or 164°/73°C.

| METHODS |

With the hope of keeping any differences as apparent as possible, I went with a pale Belgian Golden Strong Ale.

Bandages

Recipe Details

| Batch Size | Boil Time | IBU | SRM | Est. OG | Est. FG | ABV |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 4.5 gal | 90 min | 26.3 IBUs | 4.2 SRM | 1.081 | 1.015 | 8.8 % |

| Actuals | 1.081 | 1.014 | 9.0 % | |||

Fermentables

| Name | Amount | % |

|---|---|---|

| Pilsner (2 row) (Gambrinus) | 14 lbs | 100 |

Hops

| Name | Amount | Time | Use | Form | Alpha % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Magnum | 13 g | 90 min | First Wort | Pellet | 12 |

| Czech Saaz | 12 g | 30 min | Boil | Pellet | 3.5 |

Yeast

| Name | Lab | Attenuation | Temperature |

|---|---|---|---|

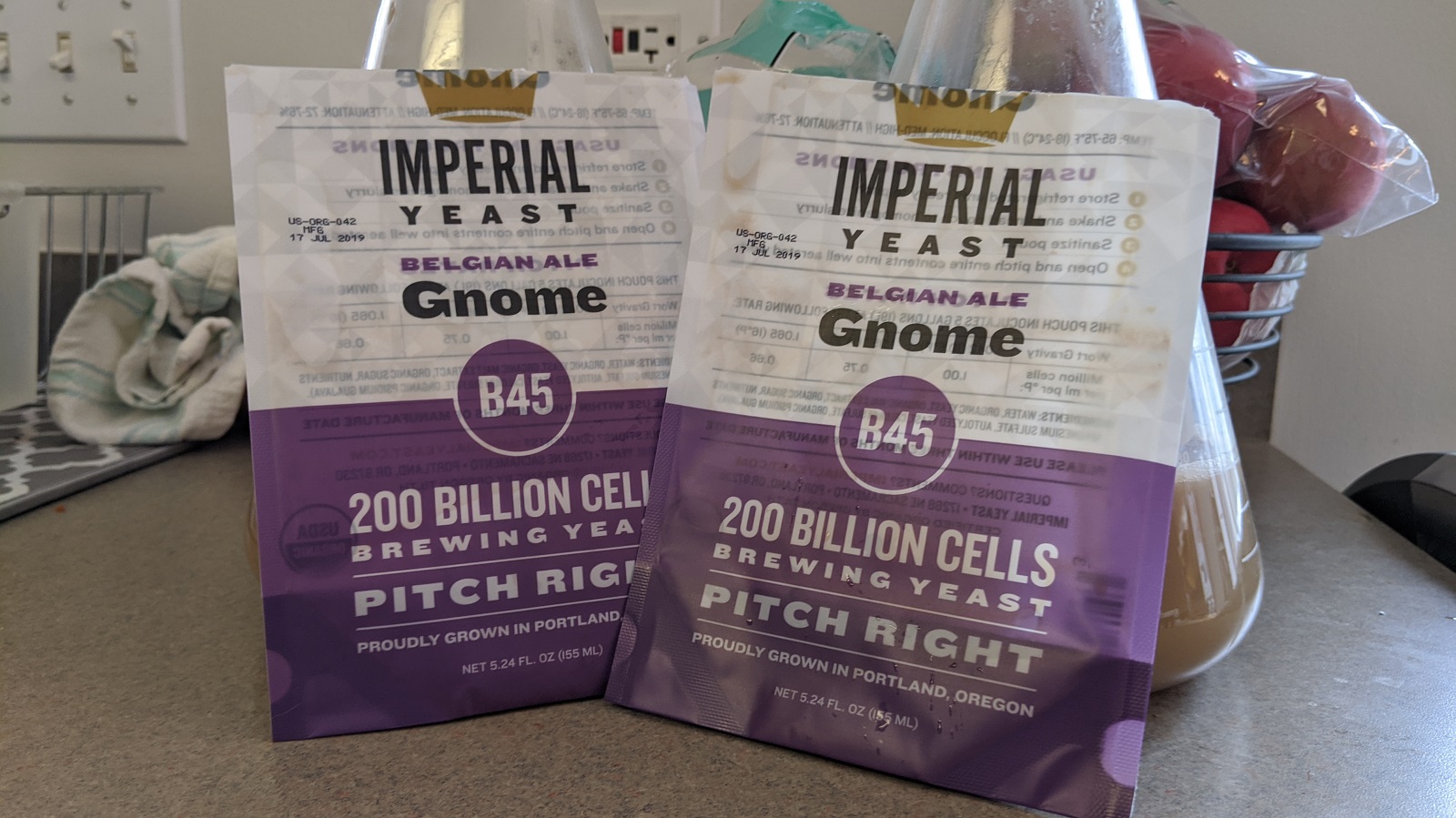

| Gnome (B45) | Imperial Yeast | 74% | 65°F - 75°F |

Notes

| Water Profile: Ca 54 | Mg 11 | Na 25 | SO4 81 | Cl 65 |

Download

| Download this recipe's BeerXML file |

I kicked off my brew day by collecting the water for each full volume batch, adjusting to my desired profile, then setting the electric controllers to heat them up.

As the water was heating, I weighed out and milled the grain for each batch.

With the water properly heated, I added the grains, kicked the pumps on, then checked to make sure both hit my intended mash temperatures of 148°F/64°C and 164°F/73°C.

Following each 60 minute mash rest, I removed the grain baskets and let the drain while the wort was heating up.

At this point, I stole some wort from both batches, briefly boiled and chilled them, then pitched a pouch of Imperial Yeast B45 Gnome into each.

Both worts were boiled for 90 minutes with hops added at the times stated in the recipe.

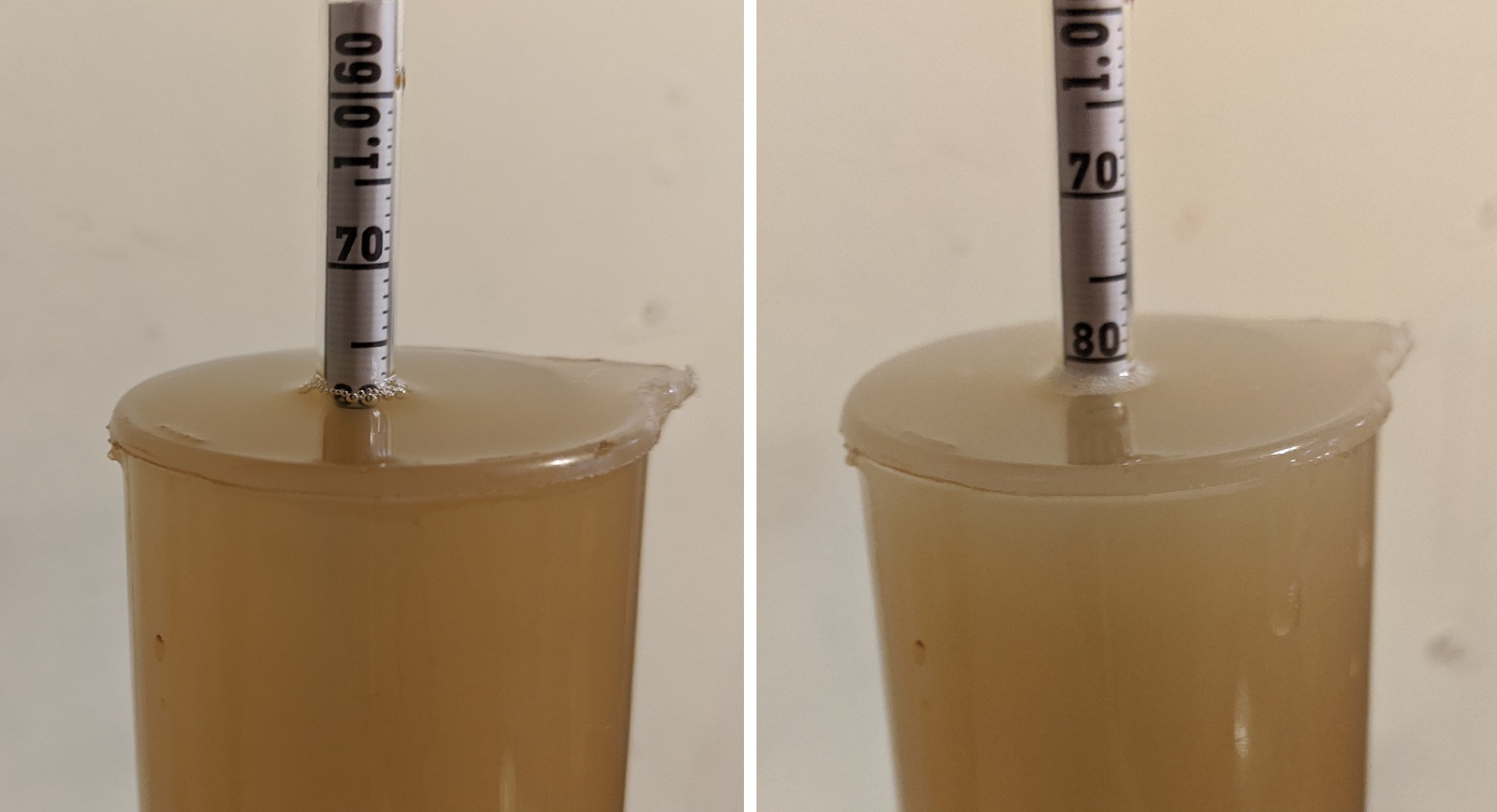

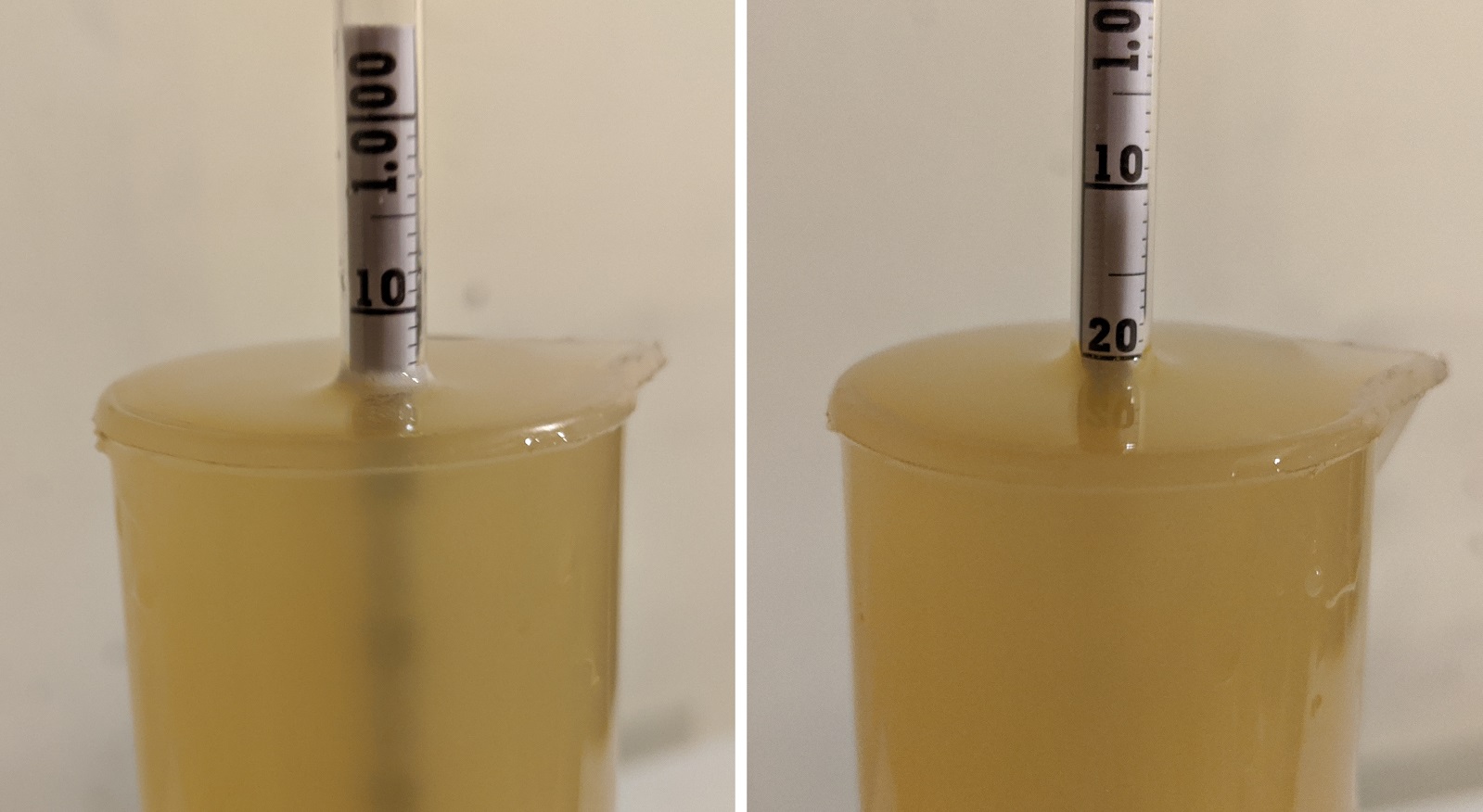

With each boil complete, the wort was chilled and racked to separate fermentation kegs, at which point I to hydrometer measurements showing a slight difference in OG.

The fermenters were placed in a chamber controlled to my desired 72°F/22°C pitching temperature and allowed to finish chilling overnight, at which point I pitched the yeast starters, set the temperature controller to 74°F/23°C, and left the beers alone.

After 3 days of fermentation, I began raising the temperature 2°F/1°C per day over 5 days until they were at 84°F/29°C, where they sat for a week to finish up. Hydrometer measurements showed the high mash temperature beer finished 0.006 SG points higher than the low mash temperature batch, amounting to 81% attenuation and 8.4% ABV for the low mash temperature beer compared to 74% attenuation and 8% ABV for the high mash temperature beer.

I left the beers alone 2 more days before verifying no change in FG and pressure transferring them to separate sanitized kegs.

The filled kegs were placed on gas in my keezer and allowed to condition a couple weeks before they were ready to serve to tasters.

| RESULTS |

A total of 23 people of varying levels of experience participated in this xBmt. Each participant was served 2 samples of the low mash temperature beer and 1 sample of the high mash temperature beer in different colored opaque cups then asked to identify the unique sample. A total of 12 tasters (p<0.05) would have had to identify the unique sample in order to reach statistical significance, though only 10 made the accurate selection (p=0.21), indicating participants in this xBmt were unable to reliably distinguish a high OG Belgian Ale mashed at 148°F/64°C from one mashed at 164°F/73°C.

My Impressions: Out of the 5 semi-blind triangle tests I attempted, I picked the odd-beer-out 3 times, which is only slightly better than chance. While bias was undoubtedly at play, if forced to describe a difference, I’d say the high mash temperature beer had a slightly more pronounced Pils malt flavor. I didn’t perceive anything I would attribute to differences in ABV, neither were particularly sweet, and both were quite tasty!

| DISCUSSION |

It is well established that mash temperature is negatively correlated with wort fermentability, and this easily measurable fact has led to the belief that it consequently impacts the perceptible dryness and sweetness of beer. It’s an idea that’s been embraced by brewers the world over for a very long time– mash low for a dry beer, mash warm to increase body and sweetness. While some contend the effect is less noticeable in simpler styles, the fact tasters in this xBmt were unable to tell apart a high OG Belgian ale mashed at 148°F/64°C from one mashed at 164°F/73°C indicates the objective difference may not lead to a perceptible one.

While the sensory analysis findings were, like past mash temperature xBmts, inconclusive, the beers were undeniably different. As expected, the beer mashed cooler had a lower FG and higher ABV than the one mashed warmer, implying mash temperature can be used as a lever to control alcohol content. This alone may be helpful for brewers of session beers where lower ABV is often accompanied by less flavor; by raising the mash temperature, one could get away with using more grain while keeping the alcohol restrained.

The lack of a perceptible differences between these xBmt beers further supports the hard-to-swallow idea that higher FG isn’t necessarily related to beer viscosity. While this has been shown to be the case multiple times now, one possible explanation is that carbonation of the beer covers up any differences in mouthfeel. A future mash temperature xBmt on a less carbonated style may provide a better understanding of this point.

More often than not, I mash my beers around 152°F/67°C and will likely continue to do so for the most part. When brewing more sessionable styles where I want a lot of flavor, I’ll definitely consider bumping the temperature up a bit, but only for the purpose of controlling ABV, not dryness or mouthfeel.

If you have any thoughts about this xBmt, please do not hesitate to share in the comments section below!

Support Brülosophy In Style!

All designs are available in various colors and sizes on Amazon!

Follow Brülosophy on:

FACEBOOK | TWITTER | INSTAGRAM

If you enjoy this stuff and feel compelled to support Brulosophy.com, please check out the Support page for details on how you can very easily do so. Thanks!

18 thoughts on “exBEERiment | Mash Temperature: Low Vs. High In A Belgian Golden Strong Ale”

Maybe those unfermented “sugars” left by a high mash temp aren’t actually sweet and have little effect on flavour. In terms of alcohol content, the low-mash temp beer is 5% stronger (8.4% vs 8%), which perhaps isn’t enough to detect in a tasting test. Imagine brewing two coffees and making one 5% stronger by adding hot water to the other.. I doubt people would pick that up when comparing one sample to another. I reckon small changes in concentrations of identical ingredients are hard to perceive, whereas beers with different malts/yeasts/water minerals are easier to tell apart.

After mashing on the low side for years for “crispness”, I now tend to mash high thanks to these exbeeriments as lower abv is definitely a healthier choice.

I was just doing to math to calculate how much difference there was between 8 and 8.4 ABV to post the same comment.

I think this could be the case, and it makes sense. If simple sugars taste sweet, and complex carbohydrates do not, then it stands to reason there’s a sliding scale in between, and a medium chain “dextrin” left in the wort may provide more body than sweetness. Of course I have no science to back that up. I do have a vague recollection of Ashton Lewis confirming as much in one of his Mr. Wizard columns ages ago. But again, it is vague!

Anecdotally, I’ve found some of my beers mashed low actually end up tasting sweeter, and I’ve wondered if it’s because the sugars left behind are simpler and thus sweeter, whereas the sugars left behind in a high mash beer are further up the scale toward complex carbohydrate.

This one actually surprises me. I would have thought there would be a thinner/watery flavor in the low temp one.

did the high mash temp have better head retention?

This was a great experiment. This is not one of those “you did it wrong” comments. Just sharing some of my experience.

Some yeasts are unable to ferment longer chain sugars. I brewed an English Brown and used Lallemand London ESB yeast. I typically mash higher because I like a “fuller” body beer. I was shocked when the beer would not ferment down past 1.025. I brewed the exact same recipe and lowered my mash temp to create a “drier” wort and was able to get the same yeast to ferment down to 1.010. I was not able to try these 2 beers side-by-side but it makes me wonder if a difference could be distinguished with such a variance in FG’s. Granted this is anecdotal evidence but I would say that the yeast used could impact results as some yeasts cannot ferment longer chain dextrins created by higher mash temperatures.

You guys are killing it!! Love how everything you do creates conversation in the brewing community. Keep doing what you are doing.

Absolutely! I think the general premise you’re going after, that the conditions of the xbmt influenced this result, is totally valid.

A difference of 6 gravity points is equivalent to about 11 ounces of sugar in a 5 gallon batch, which sounds like a lot until you realize it’s less than a half-tablespoon per 12 ounce beer. We’re also talking about maltodextrin, which is maybe 10-20% as sweet as sucrose. I think most people would fail a triangle test with distilled water when the variable was a half-tbsp of maltodextrin.

It’s certainly worthwhile to put the numbers in perspective. Makes it seem a lot less surprising.

I think one should not take the results of these xbmts as an excuse for sloppiness: mash temperature does have a measurable impact, as the measurements show. But we as humans are not particularly well-equipped to sense these differences. Perceived dryness and residual sugar are very different things – take for example the Wyeast 3711 French Saison strain, which easily attenuates the beer down to 1.000 (or sometimes even less), but leaves a notably sweet beer (which is usually attributed to increased levels of glycerol).

And also here there might be different effects canceling one another out: the yeast might consume more sugars, but produce more glycerol in the process due to the different composition of sugars in the wort. This is just a wild and probably factually incorrect guess, but we have such limited understanding of it all that it’s probably hard to debunk. Moreover, such an effect could vary by yeast strain, just like the xbmts on warm fermented lagers.

These articles are great to get the ball rolling and question the over-simplified rules of homebrewing like “ferment it over 20c and you will get an undrinkable fruit bomb” or “mash two degrees higher and it will be chewy and sweet”.

This is a really interesting breakdown, makes sense!

Cool experiment. As mentioned by someone else in the comments, my personal experience with high mash temp fermentability is that yeast selection seems to have more effect on FG than mash temp.

I’d like to see the same recipe/experiment, but the variable being one fermented at the lowest recommend temp and one at the highest. I expect the differences would be stark, but the sensory analysis might be interesting.

Nice job Matt! I liked this xbmt because it makes me think my personal view on mouthfeel in beer has more to do with protein content and yeast strain rather than FG. Although FG is certainly a factor on mouthfeel, I have found grain bill and yeast strain to be a better predictor of final flavor and mouthfeel. Like others, I have mashed high, low and in between but the final product doesn’t change much if I’m really being honest with myself. If I’m brewing an all base malt beer, I will mash higher. If using a lot of specialty malts, 20-30%, I will tend to mash on the lower end to ensure full attenuation for that grain bill.

Also like Pezell Brewing pointed out, using a yeast strain that doesn’t consume maltotrios and mashing high can lead to high FG’s. Another example of why knowing your yeast strain’s fermentation characteristics can have a greater impact than just changing your mash a few degrees.

Nice work again Matt!

It actually just came up that another iteration of this variable could likely be one that utilizes a ton of specialty malts, something we are throwing around as well.

When you have the participants taste the beers do you tell them what the exbeerament is about?

Nope, participants are not told the style of beer, or variable, prior to tasting it. I have warned people once, when it was a cider.

I like that…”warned them” it’s cider. Just so they’re not disappointed….

“This beer has the worst case of acetaldehyde I have ever tasted”

Hola Matt, gran experimento, tengo una pregunta sobre la retención de espuma y las dos temperaturas de macerado, notaste algo diferente o ambas tenían la misma retención?