Author: Phil Rusher

What is Pastry Stout? There’s no hard and fast criteria for this newfangled style of beer, but over the past several years the distinction has become widespread among craft brewers and homebrewers alike, and the lack of a clear set of “guidelines” has made for a variety of interpretations. Given the base style, most versions of Pastry Stout end up being dark, sweet, boozy, and reminiscent of something other than beer, like s’mores or coffee cake.

There are many ways to go about getting “pastry” flavors into beer, the easiest and perhaps most intuitive being to simply add the actual pastry thing during the brewing process. However, there are a variety of reasons this can be folly, particularly because pastries usually possess high concentrations of lipids that may have deleterious effects on the final product. One way to get around this is to carefully consider grain choices when brewing such a beer, opting for those known to impart rich characteristics that might emulate certain pastry-like qualities.

I’ve had the joy of using Mecca Grade Estate Malt for my last few batches and have found all of their offerings to be very flavorful. One of the sacks I have on-hand is a malt they call Opal 44, which comes with the following description:

Opal 44 is your next secret ingredient. Sweet, moderately-toasted, with hints of chocolate and raisin; its wort is reminiscent of homemade Almond Roca. The typical usage rate is 2.5 – 5%, but at 44 DP, it can be used up to 100%.

I’d been kicking around the idea of brewing a Pastry Stout for awhile, something my wife might enjoy, and the Brü Crew can make fun of me for. Wanting to keep things interesting, I decided that my first Pastry Stout would be made using a base of Opal 44 with various adjuncts added along the way to amplify the flavor.

| Making Elevenses Pastry Stout |

Along with the sensory descriptors of Opal 44, its high SRM and relatively high enzymatic power seemed like a perfect fit as the foundation of a lusciously sweet Stout. Wanting to enhance the rich malty flavors, I also included a generous portion of Vienna-style Rye malt as well as Opal 22 for a supportive graham cracker flavor. Unlike typical Stout, I opted to forgo the use of roasted grains and went with a dark Belgian candi syrup instead.

Elevenses Pastry Stout

Recipe Details

| Batch Size | Boil Time | IBU | SRM | Est. OG | Est. FG | ABV |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 6 gal | 60 min | 15.5 IBUs | 47.8 SRM | 1.086 | 1.011 | 10.0 % |

| Actuals | 1.086 | 1.02 | 8.9 % | |||

Fermentables

| Name | Amount | % |

|---|---|---|

| Mecca Grade Opal 44: Toasted Toffee Barley Malt | 15 lbs | 60 |

| Mecca Grade Rimrock: Vienna-style Rye Malt | 4 lbs | 16 |

| Mecca Grade Opal 22: Graham and Cocoa Malt | 2 lbs | 8 |

| Candi Syrup, D-240 | 1 lbs | 4 |

| Milk Sugar (Lactose) | 8 oz | 2 |

| Candi Syrup, D-180 | 1 lbs | 4 |

| Brown Sugar, Light | 1.5 lbs | 6 |

Hops

| Name | Amount | Time | Use | Form | Alpha % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hallertau Magnum | 15 g | 60 min | Boil | Pellet | 11 |

Miscs

| Name | Amount | Time | Use | Type |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cinnamon Powder | 0.50 tsp | 5 min | Secondary | Spice |

| Cacao Nibs | 9.00 oz | 7 days | Secondary | Flavor |

| Vanilla Beans | 2.00 Items | 7 days | Secondary | Flavor |

Yeast

| Name | Lab | Attenuation | Temperature |

|---|---|---|---|

| Flagship (A07) | Imperial Yeast | 75% | 60°F - 72°F |

Download

| Download this recipe's BeerXML file |

PROCESS

Given the intended strength of this beer, I made a starter of Imperial Yeast A07 Flagship a day ahead of time.

Later that evening, I continued my pre-brew preparation by collecting the full volume of RO water and milling the grain.

The following morning, I warmed up the strike water then incorporated the grains, checking to ensure it hit my target mash temperature.

After a 60 minute mash rest, I performed a quick vorlauf to set the grainbed then sparged while collecting the sweet wort.

The wort was boiled for 60 minutes with hops added as indicated in the recipe.

With about 10 minutes left in the boil, I added the lactose and D-240 Belgian candi syrup.

When the boil was finished, I quickly chilled the wort with my IC before racking it to a sanitized Brew Bucket.

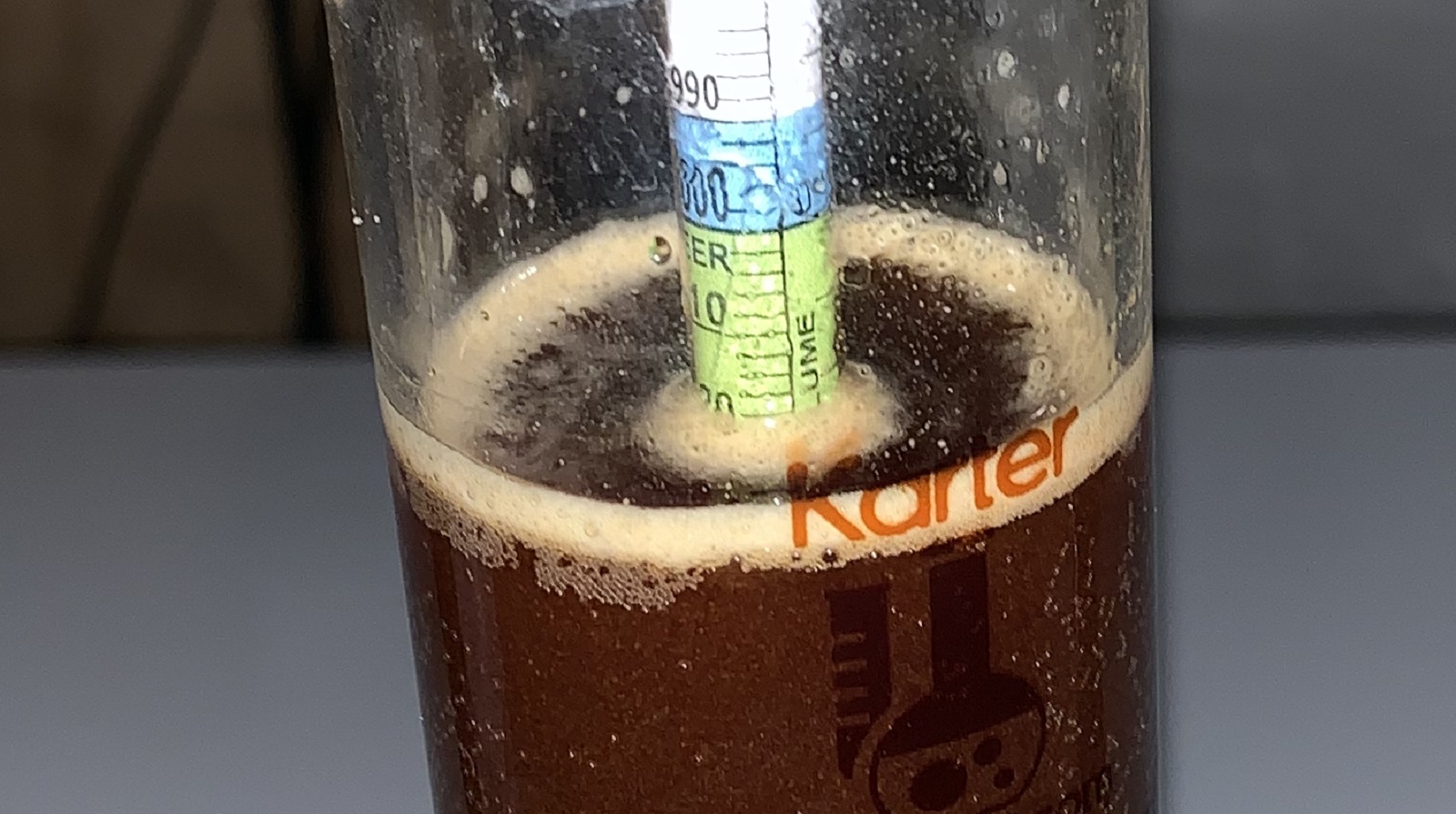

A hydrometer measurement showed the wort was sitting at a respectable 1.082 OG.

The filled fermenter was placed in my chamber and allowed to finish chilling to my desired fermentation temperature of 65˚F/18˚C, at which point I pitched the yeast starter.

Fermentation kicked off quickly and was roaring away after 2 days. At this point, I dissolved the brown sugar in boiling water and allowed it to chill for a bit before adding it to the beer.

I also added the D-180 Belgian candi syrup.

The following evening, I roasted some cacao nibs, which along with a couple chopped vanilla beans, were placed in a mason jar and covered with vodka.

After a day of soaking, I added cinnamon to the mix and gave it a good shake before pouring the entire jar into the beer.

The beer was left to finished fermented for another 4 days before I took a hydrometer measurement showing it had settled at 1.020 FG.

The beer was racked to a sanitized keg and placed in my keezer where it was burst carbonated then left to condition for a couple weeks before serving.

| IMPRESSIONS |

Part of what keeps me interested in this hobby is novelty, and the very idea of a Pastry Stout is in and of itself pretty novel. Elevenses was not only my first attempt at brewing a Pastry Stout, but it was also the first time I’d ever used what is essentially a crystal malt, Mecca Grade Opal 44, as a base malt, as well as dark Belgian candi syrups in place of roasted grains. A non-traditional approach to a rather non-traditional style.

My first unexpected observation came post-boil when I discovered the OG of the wort quite a bit lower than intended. While I tend to get slightly lower extract when brewing bigger beers, the 0.017 SG point hit in Elevenses a lot more than I’d seen, leaving me convinced it had something to do with my choice of base grain. It’s because of this that I decided to bump things up during fermentation by adding brown sugar and Belgian candi syrup, which I figured would also contribute to the pastry-ness of this Pastry Stout.

Admittedly, I was equally as nervous about how this beer would turn as I was excited. In the end, I felt the gamble paid off. To my senses, the chocolate character bordered on overwhelming yet was nicely supported by a lush malty sweetness and rich dark toffee flavors. The mild warming sensation from the higher alcohol content paired well the cool Upstate New York weather this time of year, and helped to cut through some of the richness of the beer. Generally well received by those I shared it with, I am my own worst critic and felt Elevenses may have benefited from perhaps a bit more lactose, something to add a more defined cream character.

To be clear, I’ve no plans to start swapping out standard base malts with crystal malts like Opal 44, but for an intentionally sweet style like Pasty Stout, I felt it worked out better than expected. Elevenses was one of those beers that served as my first iteration into a new style, and while I won’t be making Pastry Stout as often as I do more traditional beers, I was pleased enough with this recipe to use it as a source of inspiration for future versions.

If you have thoughts about this recipe or experience making something similar, please feel free to share in the comments section below!

Support Brülosophy In Style!

All designs are available in various colors and sizes on Amazon!

Follow Brülosophy on:

FACEBOOK | TWITTER | INSTAGRAM

If you enjoy this stuff and feel compelled to support Brulosophy.com, please check out the Support page for details on how you can very easily do so. Thanks!

22 thoughts on “Brü It Yourself | Elevenses Pastry Stout”

Nice work Phil. I’ve read on the Mecca Grade site you could use Opal at 100% and wondered how it would turn out. Although not 100% use, still a substantial % used and it still got down to 1.020! I fully expect the beer to finish between 1.030-1.040. Very cool use of those ingredients!

Thanks man! I was leery of this too but I decided to be bold. It paid.off nicely, I think.

Interesting Phil… I’ve wondered what higher concentrations of Opal 44 would do. I’ve used it only once, at 3% of malt Bill. You went way further than I would have thought of – even in my wildest dreams! But very interesting…

Have you noticed how much Bigger that beers brewed with Mecca Grade malt drink? I am on my 3rd 9-gallon batch (in past 15 months) of a Munich Helles brewed with MG Pelton Pilsner malt mostly, at 4.3% ABV. Actually closely resembles fresh Heiniken quite a lot and drinks more like a 5.0% ABV beer. Super easy drinking and a quick “go to” when I’m not sure what I want to drink or looking for a session beer.

Good Intuition about using one or both Opals in a higher alcohol Stout!

Thanks man. In my experience with MG, the beers I’ve made with those grains are undoubtedly unique. Oftentimes they drink quite smoothly no matter what, meaning a big beer like this 11% pastry stout drinks more like a 5%. So dangerous!

I was curious about your thought process regarding hop choice. I primarily brew big sweet styles and have recently been playing around with fairly high boil and aroma hop additions. I’ve been enjoying pine notes with my sweet imperial stouts and German florals with wee heavies/barley wines.

I didn’t want any discernable hop character in this beer. When making standard stouts though, I unusually stick to a solid 40-50 IBU bittering charge at the beginning of the boil and add another 10-20 IBU of something resiny for flavor.

Yep I get your point about hop character. I guess my point is similar to what you were saying about achieving pastry-like flavours through malt addition as opposed to using actual pastry (or actual chocolate or coffee for that matter). I find that there are some hop notes that don’t register as “hops” per se and that help me avoid addition of spices or other things

Ah. I’m unaware of hops that have flavors akin to spices like cinnamon, though that would make for an easier and more “beery” approach to brewing this!

A Brulosophy post about making a pastry stout is admittedly something that for some reason I never expected to see, but this is a pleasant surprise. I actually enjoy pastry stouts quite a bit. Sure, I can’t stomach a pint of one, but they’re often a lot of fun to try a 4-5 oz sample of. It’s always interesting to me how different brewers manage to bring out certain flavors, often tapping into our nostalgia for some sweet treat from our childhood.

I’ve actually done a ton of research about pastry stouts by trying some from breweries known to be some of the best at it (Angry Chair, J. Wakefield, Mikerphone, Horus, Pulpit Rock, Great Notion), listening to interviews or reading articles where these brewers talk about their process, and making some of my own. They’re definitely not as easy as a some folks seem to assume they are, and your article certainly highlights that. Recipe formulation, mash temp, boil length, sugar addition amounts and timing, multiple oxygenation steps, keeping fermentation temp low, and finishing with more residual sweetness than most of us would tend to be comfortable with are all elements that can make or break the delicate balance found in the best examples of this style.

I’m no expert by any means, but here’s a handful of pointers for anyone that wants to make pastry stouts without the trial and error I went through before getting it right:

1) Grain bill should target 3 things: high beta glucan content, little to no roast with chocolate in it’s place, and a fair amount of residual sweetness without being just sugar flavor. Maris Otter and Golden Promise both make good base malts for this, and a mix of Caramunich III and a few caramel/crystal malts will help get the right amount of complexity and residual sweetness.

2) Mash high, boil long. You want plenty of unfermentable sugar as well as some carmelization. I’ve gone as long as 6 hours on a boil for a pastry stout but I’d recommend 2-3 hours generally. This obviously uses more water due to evaporation, but it will get those tasty maillard products and a more viscous body.

3) Aim for a starting gravity between 1.100 and 1.120 (I’ve started as high as 1.155). Hit it with pure oxygen for 60 seconds before pitching the yeast, then do it again 12 hours later. Definitely use some yeast nutrient too, and pitch a shitload of active, healthy yeast. Take your definition of “shitload” then pitch more than whatever that is.

4) Try to keep fermentation temp between 62-65 to further limit the chances of fusel production. If you have the ability to ferment under pressure, put under 15psi after day 2 or 3.

5) Final gravity should be 1.030 at the absolute minimum, but 1.040-1.050 is more common. Yes I know that’s high and you just shat yourself when you read it. I didn’t believe it either until I experimented with it. Obviously this also comes down to personal preference as well though.

6) Keep your target final gravity in mind when you choose your yeast strain. If you want a higher final gravity, then you may be better off going with a strain that tends to be less attenuative and isn’t known to go past it’s published alcohol tolerance.

7) Unless you end up with a lower OG than expected and need to bump it up with some sugar like Phil did (been there Phil), let fermentation finish and see where your gravity lands, then adjust accordingly. I’ve tried starting with a really high gravity vs starting lower and making multiple sugar additions, and the sugar addition method results in a slightly lower final gravity but otherwise no difference.

8) If you feel like you need just a bit more body but don’t want to make it taste sweeter than it already is, use maltodextrin.

Phil, I noticed you’re mashing in a keggle rather than an insulated vessel. How much temperature do you normally lose during a mash using this method? Do you fire up the burner to regain lost heat?

It depends! If I’m brewing in the summer then the heat loss to the environment is nominal. Like, low enough to completely ignore. But if it’s a bit chillier outside then I do lose some heat so I tend to turn on the heat and stir up the mash as needed. Maybe every 10-15 minutes, depending.

Amazing advice. Thank you for all that

Thank you for this!

Was gonna come here to comment this. The FG needs to be significantly higher.

Does it? We’ve shown that it’s really difficult for tasters to discern a beer that finished about 15 SG lower than another one that was otherwise very similar. In practice, I myself have had a hard time detecting any sort of extra sweetness from high terminal gravity. What’s more is that this pastry I made was most definitely quite sweet.

I guess my point is that terminal gravity is not a great indicator of perceived sweetness.

Tyson nailed it. I have brewed for one of the aforementioned breweries and everything he said was on point. I am surprised your target temp was only 146 given the style.

Thanks Robert. Glad to hear from someone with direct experience that my research lead me to the right method. Cheers!

Again, there are no hard and fast rules here. But given the fact that it is very difficult to discern differences in perceived sweetness from final gravity, having a high FG was not my goal, rather, fermentability was.

My home brewing journey is really just beginning. I’m only 3 1-gallon batches deep. With that said, pastry stouts and funky sours are the direction I hope to be headed. How do you feel you’d modify this recipe if you were to make it a German Chocolate Cake Pastry Stout?

I think this might depend on your interpretation of German chocolate cake. I’ve seen recipes with coconut, walnuts, raspberries, you name it. Once you decide which flavors you want in the final beer you can go from there, but usually this means starting with thinking about how you can impart those flavors from the grain itself. Read grain descriptors and if you can, go out and get small samples of the grain you’re looking at to see what they smell and taste like. One of the best ways to get a good idea of how grain will taste in a beer is to literally chew on it for a few minutes. If you’ve got the time and means, doing a hot-steep is even better than chewing on the grain. It’s basically like making “tea” using pulverized brewing grain.

Once you’ve decided on your grains, your next step might be to add heaps of chocolate flavor, and the the answer to that is simple: make your stout beer as you normally would but add generous amounts of cacao in the fermentation vessel. If you are adding other flavors like coconut you can do that at this point as well. Whenever I make a beer with flavors that are not derived from the grain or hops, I’ve found that they really shine through best after the boil, so I will usually make these flavor additions at the tail end or after the yeast have done their job.

What are the substitutes for people who cant get mecca grade stuff??

Craft maltsters may be apt to say that there aren’t any substitutes ;). But it’s definitely true that most any craft malt is completely unique, and the stuff that comes from Mecca Grade is exceptional; I can’t say enough how great they are. They do sell direct to consumer through their website but I’m not sure whether or not they ship internationally.

My goal with this beer was to make a sweet stout that had no roasted grains, so I’d bear that in mind when trying to use different ingredients. For example, you might start by using a very sweet base malt like Vienna or maybe a lighter colored Munich. From there I’d try subbing in generous amounts of rye malt and something like Victory or Aromatic malt. You can add color and sweetness through the candi syrups I did as well.