Author: Brian Hall

Strong beers, Barleywine in particular, have grown in popularity over the years among craft drinkers, with barrel aged “this” infused with “that” becoming sought after and traded across the country. With some of these beers fetching strikingly high prices, there’s incentive for homebrewers to try their hands at the art of big beer brewing. The trick is being able to produce such a beer that possesses the alcohol punch without the burning off-flavors.

When brewing high OG styles, convention dictates large amounts of yeast and oxygen are paramount to ensure a healthy fermentation, both of which help promote healthy yeast, assist in reducing the risk of off-flavor development, and encourage adequate attenuation. One unique method that has been employed by some brewers of such beers involves starting fermentation with a lower volume then gradually adding more wort to the fermenting beer over time. This is a technique some bigger breweries employ to make double or triple batches, but for high OG beers, these additions can be strung out over a much longer a much longer period.

Not too long ago, I read an article about a brewer who’d fermented a strong beer using this method, and they reported good results. Having been a fan of some big beers brewed here in Anchorage over the last few years, I decided to try it out for myself on a beer of epic proportions.

| PURPOSE |

To evaluate the differences between a high OG beer where the full volume is fermented at once and the same beer where yeast is pitched into a smaller volume and wort is gradually added over time.

| METHODS |

Naturally, the recipe I chose for this xBmt had to be one of high OG, and wanting to really emphasize any impact of the variable, I designed a Barleywine that more than hit the mark in terms of size.

Brian’s Big Boy Barleywine

Recipe Details

| Batch Size | Boil Time | IBU | SRM | Est. OG | Est. FG | ABV |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5.5 gal | 60 min | 49.0 IBUs | 15.8 SRM | 1.179 | 1.108 | 10.0 % |

| Actuals | 1.179 | 1.085 | 13.3 % | |||

Fermentables

| Name | Amount | % |

|---|---|---|

| Pale Malt (2 Row) US | 40 lbs | 97.56 |

| Caramel/Crystal Malt - 20L | 8 oz | 1.22 |

| Special B Malt | 8 oz | 1.22 |

Hops

| Name | Amount | Time | Use | Form | Alpha % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Galaxy | 57 g | 60 min | Boil | Pellet | 16.1 |

| Galaxy | 29 g | 15 min | Boil | Pellet | 14 |

Yeast

| Name | Lab | Attenuation | Temperature |

|---|---|---|---|

| Tartan (A31) | Imperial Yeast | 73% | 65°F - 70°F |

Download

| Download this recipe's BeerXML file |

After collecting the water for this large batch, I used a heat stick to start heating it to strike temperature.

With the water warming up, I measured out and milled the grain.

Approximately 7 hours later, the water was at the proper temperature, so I mashed in, stirred to eliminate dough balls, then checked to make sure it was sitting at my target mash temperature.

At this point, I moved on to preparing a couple starters of identical size using Imperial Yeast A31 Tartan.

The mash, covered and wrapped in insulation, was left to rest overnight.

The following morning, 13 hours after mashing in, I collected the sweet wort, sparged to reach 45 gallons/170 liters, then brought it to a boil using both propane and a heat stick.

My goal being to produce a very high OG wort, I ended up boiling for 6 hours, transferring it to a smaller kettle in the last hour to make for easier chilling.

A hydrometer measurement showed the wort was at 40 °P, which equates to 1.179 OG. Mission accomplished!

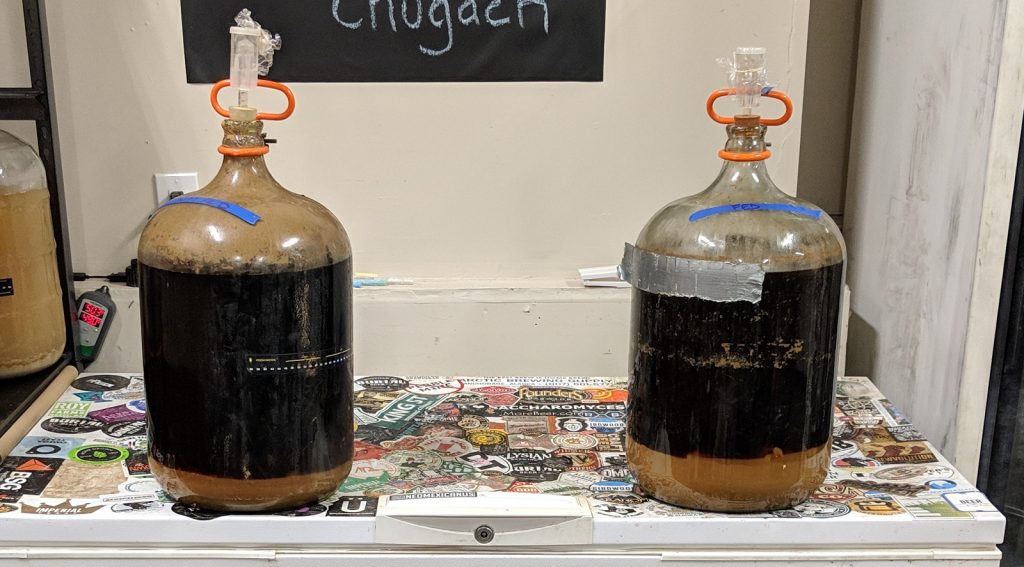

After filling one carboy with 5.5 gallons/21 liters of wort, I racked 1 gallon to a second carboy then transferred the rest into multiple canning jars that were stored in my refrigerator.

Both carboys were placed next to each other in my ferm chamber controlled to 66°F/19°C. At this point, I combined the yeast starters, shook to homogenize, then pitched equal volumes into each batch.

Just 2 hours later, both beers were showing signs of activity.

Starting 2 days into fermentation, I began adding 0.5 gallons/2 liters of wort to the lower volume batch every other day until it reached the same volume as the standard ferment batch.

I left the beers alone in the chamber for a month before taking hydrometer measurements showing both beers finished at the same FG.

Given the high OG, I expected the beers to finish slightly high, but not 1.084 FG, so I raised the temperature in the chamber and left the beers alone for a few more days. Alas, no change. Not wanting to introduce any extraneous variables, the crew talked me out of following my urge to pitch new yeast or add enzymes, so I prepared the beers for packaging. It was at this point I noticed a larger trub cake on the batch that was gradually dosed with wort during fermentation.

I racked the beers to sanitized kegs, placed them in my keezer on gas, and let them condition for a few weeks before serving them to unsuspecting participants.

| RESULTS |

A total of 20 people of varying levels of experience participated in this xBmt. Each participant was served 1 sample of the beer fermented at full volume and 2 samples of the beer where wort was gradually added during fermentation in different colored opaque cups then asked to identify the unique sample. While 11 tasters (p<0.05) would have had to identify the unique sample in order to reach statistical significance, only 4 (p=0.94) made the accurate selection, indicating participants in this xBmt could not reliably distinguish a very high OG beer fermented at full volume from one where the wort was gradually added over time.

My Impressions: These beers tasted identical to me and I was unable to consistently tell them apart in multiple triangle test attempts, every one was a guess. As for the beer itself, the only way I found to drink it was to fortify it with Brandy to create some sort of Port-like Barleywine thing, but now that data collection is complete, I’ll be employing methods to drop the FG to a more reasonable level.

| DISCUSSION |

There are a number of consideration brewers high OG beers make with every batch, namely ensuring an adequate pitch rate and avoiding a stalled fermentation. By pitching yeast into a smaller volume of beer then gradually adding wort over time, one ensures a higher initial pitch rates are high while ostensibly limiting yeast stress, which some have claimed encourages attenuation and decreases the risk of off-flavor development. However, tasters in this xBmt were unable to distinguish a beer made using this method from one fermented at full volume, suggesting it had little if any perceptible impact.

The thinking behind this wort feeding approach has some face validity– given identical amounts of yeast, a lower volume of beer will unarguably be pitched at a higher rate, meaning less initial stress and improved viability throughout the fermentation process. Curiously, in addition to tasters being unable to these beers apart, no objectively measurable differences were noted either. Fermentation lag time, OG, and FG were all essentially identical between the batches.

When considering possible explanations for these results, a few things come to mind. First, both received a fairly solid pitch of yeast, and it seems plausible that a lower initial pitch rate may have led to more noticeable differences. Of course, it’d be naive to ignore the fact these beers finished with a FG higher than what many big beers start at, which as many tasters noted, made it difficult to drink. Both were sweeter than a Port wine and had no fortification to help cut that sweetness, which may have gotten in the way of any differences caused by the variable. While I intentionally went with such a high OG beer as a way to test if gradually feeding wort during fermentation affects attenuation, I’m afraid I may have taken things bit too far.

Having made several batches of Barleywine with more normal OGs, several since brewing the beer for this xBmt and none using the wort feeding method, I’m not convinced gradually adding wort during fermentation is as beneficial as some claim. With adequate pitch rates and oxygenation, I find the big beers I brew come out tasting great. As such, the only feeding I plan to do in the future is simple sugar additions, and with all these mason jar sitting around, I think I’ll take up pickling as well.

If you have any thoughts about this xBmt, please do not hesitate to share in the comments section below!

Support Brülosophy In Style!

All designs are available in various colors and sizes on Amazon!

Follow Brülosophy on:

FACEBOOK | TWITTER | INSTAGRAM

If you enjoy this stuff and feel compelled to support Brulosophy.com, please check out the Support page for details on how you can very easily do so. Thanks!

25 thoughts on “exBEERiment | Impact Of Gradually Adding Wort To Fermenting High OG Beer”

Wonder how this would work if you started with lower OG (1.050-1.070) and then added wort? a bit less shock? maybe a few blasts of O2? For an old DFH 120 clone we added sugar (and hops) over 8 days and hit wort with O2 the first 2 days as well.

I’m confused by what was written. “Given the high OG, I expected the beers to finish slightly high, but not 1.084 FG, so I raised the temperature in the chamber and left the beers alone for a few more days” This seems directly in contradiction to the fact (as written in the recipe table) that the expected FG was 1.108 and the actual was 1.085. So, it seems that it finished quite a bit LOWER than you expected. Why did you think that something was wrong or that raising the temperature would do anything at all? What am I missing here?

Dumb question–Is an overnight mash common? Bacteria and yeast were everywhere presumably? What was the philosophy behind this?

Probably due to the 6+ hour boil, they wanted to split the batch into 2 sessions. Just my guess

Overnight mashes are reasonably common, yes. For some of us it makes it easier to brew by splitting up the brewing process into reasonable time chunks. I’ve never had a single batch go off this way.

I wonder if staggered nutrient additions and degassing would have made a difference like we do when making mead?

The bittering seems really low for a beer with this high of a OG, I think I had 300 IBU (theoretically) with the 15% abv DF120 style beer I made and it still was a tad under bittered.

Also, I was under the impression that you had to start the yeast out at a normal OG range (say 1.090) and then add concentrated wort (say 1.180) gradually so that the combined Gravity goes up slowly. The way you did it, the yeast were exposed to the super high osmolarity right away, just a lower volume, which doesn’t change the concentration of sugar.

Sorry, but you didn’t really test the variable you were trying to test, unless I am confused haha.

The way I have heard about stepping it up would be either in the way above or by doing sugar additions in stages to bring the gravity up.

In this experiment I think you tested “does it matter how many yest cells you pitch into a hostile environment?”

Now tell us more about this brandyport… Did you try fortifying it with different spirits?

I meant to type barleyport, but was too clever for myself.

What a bizzare exbeeriment. I had to go check to be sure, but that strain has a listed alcohol tolerance of 10%, which you exceeded by 2-3%, so good job yeasties, but like.. that fg was never gonna drop to a “normal” range without some highly alcohol tolerant bugs in it.

This makes the most sense. Sounds like alcohol tolerance of this strain is too low for the OG of that wort. Something with a higher tolerance may have been a better choice.

Regarding the alcohol tolerance of the strain…wouldn’t that be the first thing that anyone would check at the outset when setting up the recipe?

Interesting, but unfortunately it doesn’t really seem all that applicable for 99.9% of the beer people brew. I would have designed it as:

Batch A) 1.090 OG, 6gal, large yeast starter, all at once.

Batch B) 1.090 OG, 1 gal, old yeast / underpitch, and step feed 1gal per day, up to 6.

Essentially an on-the-fly step-up starter, vs a pre-made yeast starter

With wlp099, white labs sugests that you mash a beer with low OG, and than add more fermentables in order to achieve high abv 16+. Maybe Then we’ll notice more differences

After reading your impressions and discussion, I REALLY want to hear Jersey and Tim review this beer.

This.

😂😂😂 Jersey and Tim review needs to happen for this beer.

“sparged to reach 45 gallons”

Wait, did you really boil off 34 gallons? That is…something?

yes the 34 gallon boil off does seem amazing. (like many of these experiments, I’m still struggling to figure out if the procedure is what was done or if there are typos/poorly written parts. Often times the logic and underlying philosophy don’t make much sense to me.) If there was such a long boil, I’d be interested in seeing a tasting profile of this. How did it age? I routinely brew big beers (and to be honest was really happy to see a beer on here that wasn’t another “crushable” pilsner (what does “crushable mean?”)) but don’t go through all this rigmarole.

It seems like A31 Tartan is only rated for 10% ABV according to Imperial’s website. I calculated your ABV using a formula which corrects for higher OG, you actually reached 16.4% AVB! I think those yeasts would have given up no matter what you did, that wort started so very concentrated.

Formula for high ABV beers: %ABV =(76.08 * (OG-FG) / (1.775-OG)) * (FG / 0.794)

This accounts for the differing densities at high OG and/or ABV. the scale is not linear.

Oh, and just for fun I calculated the calories for a 12 ounce serving, 699 Calories!

Where did you get the idea that a 1.179 OG beer would be drinkable? 🙂

No response to these comments from any member of Brulosophy?

Yeah, they screwed this one up.

First and foremost, I applaud your attempt at brewing a ridiculous beer. I agree with several of the other commenters in that I’ve typically seen this type of stepped, high-gravity fermentation managed by starting at a lower gravity and stepping up by adding more fermentables (dextrose, sucrose, DME, etc.) every few days. The hypotheses are that A) a high initial sugar concentration is detrimental to yeast because of high osmotic pressure and B) yeast have the ability develop alcohol tolerance over time.

I’d also consider a bit lower of a starting OG. The 1.130-1.150 range will still make a very big beer, and is a bit more reasonable for the yeast. My biggest barleywine started at 1.142 and finished at 1.024. This was all malt, and didn’t use sequential feedings at fermentation. I did use a big pitch of yeast that was stepped up from a 1.045 beer to a 1.070 beer first to grow the pitch and develop some alcohol tolerance before the really big beer.

I think this was a really cool xBmt, and I hope to see more like this with big beers. Those of us who like to push the limits love this stuff. Ideas for future xBmt’s would be stepped fermentation with DME added in stages to a lower OG beer vs. starting at full gravity. Also, I’d love to see a comparison of yeast that have been stepped up through higher gravity/alcohol wort vs. yeast started in a traditional 1.030ish starter for a super high gravity beer like this.

In the fuel ethanol world, where this is fairly common, it would be termed a fed batch fermentation.