Author: Jake Huolihan

Of the multitude of advice given to the new brewer looking to up their game, the most common suggestions often relate in some way to yeast health, particularly the importance of pitching the proper amount of the freshest yeast possible. In fact, many believe the overall improvement in homebrew over the last couple decades is largely due to the availability of higher quality yeast.

When it comes to yeast freshness, the primary concern has to do with viability, which refers to the total amount of living cells in a given volume of yeast. While it’s impossible to determine an exact rate at which yeast cells die, it’s commonly accepted that a specific volume will lose approximately 20% of its remaining cells on a monthly basis. So, if we assume a fresh pouch of yeast has 200 billion viable cells on the date it is manufactured, one can assume it will be at 160 billion cells a month later, 128 billion cells a month after that, 102 billion cells after 3 months, and so on. It’s for this reason yeast labs include the date it was manufactured on the package as well as recommend using it as soon as possible.

For the most part, I’ve adhered to these recommendations by propagating older pouches in a starter, or occasionally pitching multiple packs of yeast to improve viability. However, based on some surprising results from previous xBmts, I’ve found myself being a bit more lax and have been pitching single pouches of yeast directly into fresh wort, some not quite as fresh as they could be. While my anecdotal experience with these beers has been rather positive, I was curious what, if any, impact this arguably shoddy practice was having on my beer and put it to the test!

| PURPOSE |

To evaluate the differences between beers fermented with a direct pitched pouch of yeast packaged either 1 month or 4 months prior to use.

| METHODS |

For this xBmt, I went with a fairly clean British Bitter fermented Imperial Yeast A09 Pub, a strain known for imparting a certain degree of esters.

Baby Back Bitter

Recipe Details

| Batch Size | Boil Time | IBU | SRM | Est. OG | Est. FG | ABV |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5.5 gal | 60 min | 53.4 IBUs | 9.6 SRM | 1.055 | 1.012 | 5.7 % |

| Actuals | 1.055 | 1.008 | 6.2 % | |||

Fermentables

| Name | Amount | % |

|---|---|---|

| Special Pale (Cargill) | 11.5 lbs | 95.34 |

| Crystal, Medium (Simpsons) | 9 oz | 4.66 |

Hops

| Name | Amount | Time | Use | Form | Alpha % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pekko | 15 g | 60 min | Boil | Pellet | 15 |

| Pekko | 15 g | 30 min | Boil | Pellet | 15 |

| Pekko | 15 g | 5 min | Boil | Pellet | 15 |

Yeast

| Name | Lab | Attenuation | Temperature |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pub (A09) | Imperial Yeast | 72% | 64°F - 70°F |

Notes

| Water Profile: Ca 91 | Mg 0 | Na 8 | SO4 149 | Cl 55 |

Download

| Download this recipe's BeerXML file |

After collecting my grains the night before brewing, I prepared the water by adjusting it to my desired profile then scheduled my heat stick to turn on a few hours before I planned to start the next day.

The following morning began with the milling of grain.

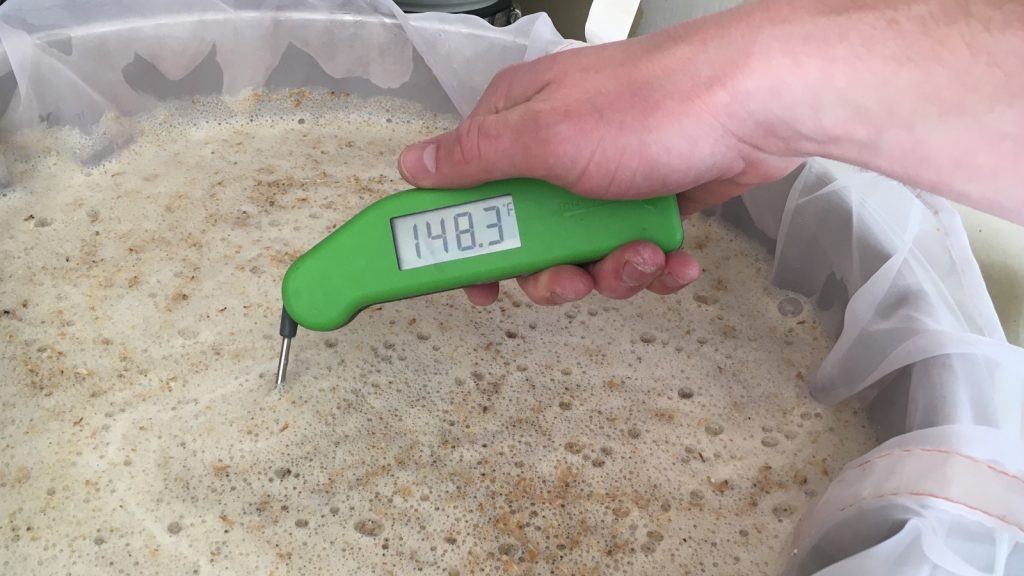

With the water properly heated, I incorporated the grist then checked to ensure it hit my target mash temperature.

The mash was left to rest for 60 minutes during which I stirred every 15 minutes with my large whisk.

With the mash step complete, I collected the sweet wort in a kettle.

The wort was then boiled for 60 minutes, during which the hops were added at the times stated in the recipe.

Once the boil was complete, I quickly chilled the wort.

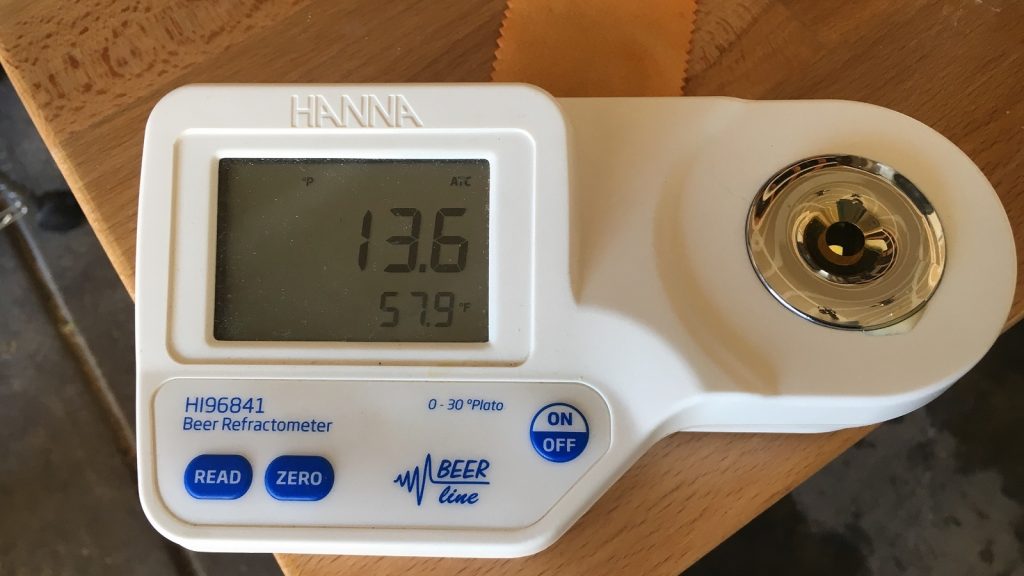

A refractometer reading showed the wort had achieved my target OG.

Equal amounts of wort were then transferred to a pair of identical fermentation vessels.

After connecting the filled fermentors to my glycol chiller set to maintain both at 66°F/19°C, each was direct pitched with a single pouch of Imperial Yeast A09 Pub, one packaged a month earlier and the other packaged 4 months prior. Based on commonly accepted assumptions about viability loss over time, this would equate to the fresh and older pouches having approximately 160 billion and 82 billion cells, respectively.

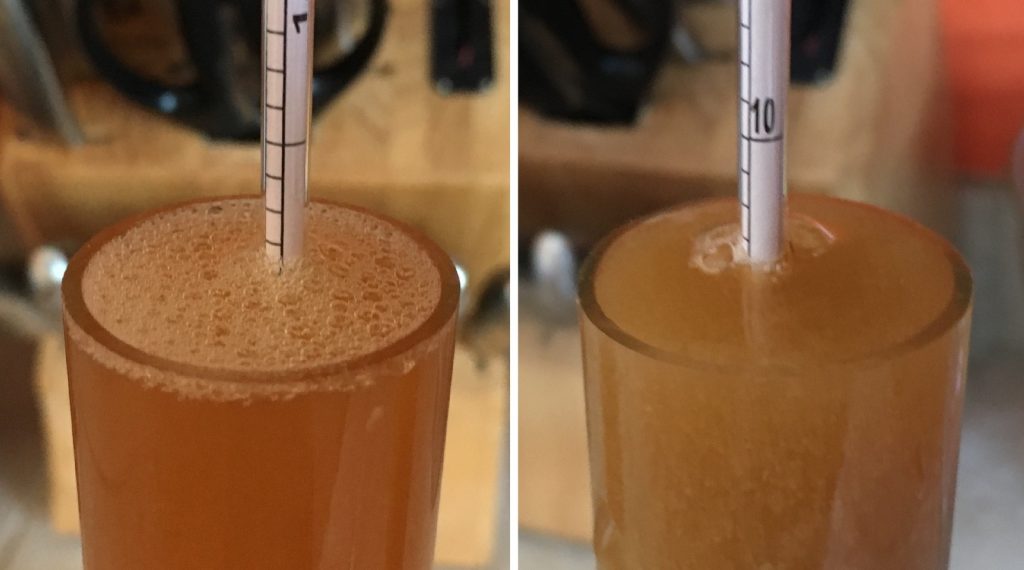

I observed fermentation activity in the beer pitched with fresh yeast just a few hours after pitching, while the beer pitched with older yeast didn’t get going for another 6 hours. After a week of fermentation, I pulled samples and noticed a rather stark difference in appearance.

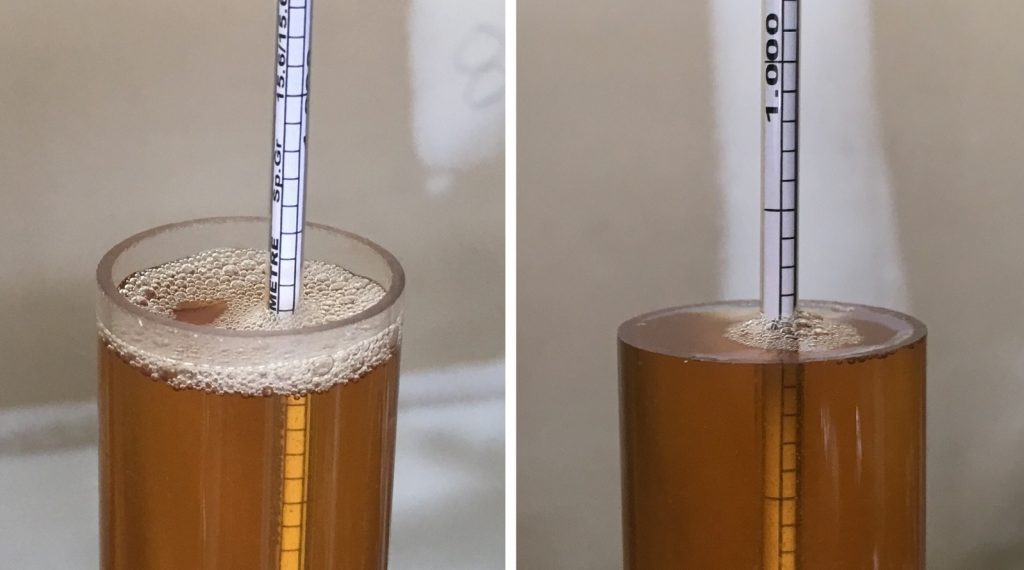

Hydrometer measurements at this point suggested the beer pitched with fresh yeast was likely done fermenting while the beer pitched with older yeast still had a ways to go.

I left the beers alone for another week before taking a second set of hydrometer measurements indicating both had attenuated to the same FG.

The beers were then racked to separate kegs.

The filled kegs were placed in my keezer where they were burst carbonated overnight before I reduced the gas to serving pressure. Even after 10 days of conditioning, the beer pitched with older yeast appeared noticeably more hazy than the one pitched with fresh yeast.

When it came time to collect data 12 days later, the beers looked much more similar.

| RESULTS |

A total of 20 people of varying levels of experience participated in this xBmt. Each participant was served 1 sample of the beer pitched with fresh yeast and 2 samples of the beer pitched with older yeast in different colored opaque cups then asked to identify the unique sample. While 11 tasters (p<0.05) would have had to accurately identify the unique sample in order to reach statistical significance, only 8 (p=0.34) did, indicating participants in this xBmt were unable to reliably distinguish beers fermented with yeast packaged 1 month prior to use from the same beer fermented with yeast packaged 4 months prior to use.

My Impressions: Over the 5 triangle tests I attempted, being fully aware of the variable and even with the slight difference in clarity, I was unable to consistently identify the odd-beer-out. To me, the beers smelled and tasted identical, which was a great thing because it was a killer Bitter!

| DISCUSSION |

It goes without saying that freshness of ingredients, whether in food or beer, is universally viewed as a prime contributor to quality, and this couldn’t be more true in the case of yeast. It’s well established that yeast loses viability over time and, if too old, can lead to poor results. However, many modern brewers fret over using yeast that’s anymore than just a couple weeks old for fear of sluggish or even stuck fermentations as well as off-flavor development. The fact tasters in this xBmt were unable to reliably tell apart beers pitched directly with yeast that was either 1 month or 4 months old suggests age, at least within reason, may not guarantee a bad outcome

Despite the apparent similarities between these beers in terms of aroma, flavor, and mouthfeel, there were some easily observable objective differences when it came to fermentation. Not only did the beer pitched with fresher yeast have a shorter lag phase, which ostensibly reduces the risk of other microbes having an impact, but it finished fermenting sooner than the beer pitched with older yeast. Moreover, fermenting with fresh yeast also seemed to expedite the beer clarification process, which may or may not be considered a positive depending of stylistic preferences.

Considering these results along with those from previous xBmts on both pitch rate and yeast freshness, I’m curious at what point age would have a perceptibly detrimental impact. Would 2 year old yeast that’s propagated to the same viability as a fresh pouch produce good results? Either way, I’ll continue to use the freshest yeast possible, as it seems the best way to ensure strong fermentation and quality beer.

If you have any thoughts about this xBmt, please do not hesitate to share in the comments section below!

Support Brülosophy In Style!

All designs are available in various colors and sizes on Amazon!

Follow Brülosophy on:

FACEBOOK | TWITTER | INSTAGRAM

If you enjoy this stuff and feel compelled to support Brulosophy.com, please check out the Support page for details on how you can very easily do so. Thanks!

12 thoughts on “exBEERiment | Impact Yeast Freshness When Direct Pitching Has On A Strong Bitter”

“it’s commonly accepted that a specific volume will lose approximately 20% of its remaining cells on a monthly basis”

At room temperature, in the fridge or either way?

I don’t think anything is really commonly accepted about this. I have heard the thumb rule of 10% loss per month, also 20% loss, and recently heard a much less number – directly from a yeast manufacturer (viability after 1, 2, 3… months: 99.21%, 98.05%, 90.26%, 84.28%, 79.35%, 71.59%).

I think 4 months was too few for this experiment.

Regardless, thank you, as always.

With Imperial A04 yeast at the end of its shelf live (5-6 month) I had significant ester production (perceived as an of flavor by a professional brewer) despite making a starter, it was still an underpitch.

It would be interesting to repeat the same experiment with bottom fermenting yeast. From my limtited observations bottom fermenting yeast ages faster. I think top fermenting yeast goes to sleep in the fridge, while the metabolism of bottom fermenting yeast stays still active since storage temperature is identical to fermentation temperature.

There exists a white labs video where they go into detail about yeast qualities and practices.

They called out under pitching on purpose to enhance or increase the character of the yeast when desired.

So if it’s a slightly ester producing strain you should get more esters via more reproduction in an under pitch.

Hi Steve!

Nice one Jake! You mentioned a sugar addition in the article but I didn’t see it in the recipe. Was that a typo in the article or the recipe? I only ask because I might be inclined to make this one since you said it was killer. Thanks!

That is a typo there were no simple sugar additions. Good luck brewing this let us know how you like it, I’ve brewed this same recipe quite a few times it’s good.

Great exbeeriment! I would love to see it repeated with a lager yeast. Maybe you have done a comparison with high and low pitch temp on lagers. From my experience no single package of lager yeast has enough cells for pitching a lager in the 40’s or low 50’s without observing a 2 or 3 day lag or having to remove from cooling and let warm to 60F until active. (Maybe a low gravity with fresh package). So one could compare a fresh imperial pack to a large starter and cold pitch at 40 to 50 F Perhaps do 4 2.5 gallon batches. Two pitch cold say44F and two pitch hot at 68F Each has a large starter and old package. This experiment would also investigate the interaction of yeast cell count and pitch temp. Keep up the great work. Cheers

Interesting stuff. You could interpret this experiment as another pitch rate test, backing up previous results showing that pitch rate appears not to affect flavour in a significant way. That makes sense to me – provided there’s enough oxygen, yeast will always multiply and make up the numbers, whether in a starter or in the main wort. The only downside is a slightly longer schedule.

I’ve recently had success building up a starter from 13 month old yeast. I originally collected an approximate 100billion cells from an overbuild starter and stored it in a sealed jar and refrigerated. Strain was WLP590 French Saison. 13 months later the viability was approximately 3% according to the 20% loss formula, and I built up a multi step starter from 0.5L to 1.5L to get to pitching rate. The beer turned out great, and no off flavors or clarity issues. I couldn’t perceive any significant difference to the same beer brewed originally 13 months prior.

The problem here is that Imperial guarantees their yeast for 4 months. So, all this test did was compare the same yeast strain at 2 different points within its “guaranteed fresh” range.

Reference: (Imperial FAQ) “We recommend using the freshest possible yeast and we back our yeast for 4 months from the manufacture date on the front of the pouch.”

Weighing in 3 years late. This is interesting. Yet, if I’m reading the following abstract correctly, older generations of propagated yeast ferment more efficiently “than mixed aged or virgin cell cultures.” Thoughts? https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/12702447/