Author: Marshall Schott

The ability to shop for ingredients and gear from the comfort of one’s home is a huge convenience afforded to modern brewers. While online shops are generally able to guarantee a certain level of freshness, there’s only so much they can do to control the conditions in which products are shipped. Thankfully, this isn’t really an issue for most brewing wares, but it is certainly something to consider when it comes to yeast.

It’s become common knowledge that yeast is best kept cool prior to being pitched, as lower temperatures reduce the rate at which yeast consume their glycogen reserves. This is important because glycogen contributes to stronger cell walls, and hence depleted reserves can lead to weak cell walls that are more susceptible to rupturing during fermentation. When cells pop, the stuff that’s inside ends up in the beer it was intended to ferment, which can lead to off-flavors associated with autolysis.

Most brewers these days are keen enough to store their yeast in a refrigerator until use, but it’s difficult to account for the way it’s treated when being shipped. Many shops offer to wrap yeast in ice packs for a small fee, but even this has little effect when shipping takes multiple days or during warmer months.

We receive our yeast direct from Imperial Yeast, who package it in insulated styrofoam boxes with numerous ice packs, and they make sure we receive it next day. Even in the middle of summer, the yeast arrives cold. Imperial Yeast’s Casey Helwig had mentioned to me how important this is to them, and how frustrating it can be to hear that shops don’t treat their yeast with as much care as they should. With Casey in town for the holidays, the opportunity arose for a collaboration xBmt, so I proposed we test out the impact of yeast storage temperature.

| PURPOSE |

To evaluate the differences between beers fermented yeast that was stored in either cool or warm environments.

| METHODS |

In designing this xBmt with Casey, we determined an English yeast strain would be good for this variable and came up with a simple British Golden Ale recipe.

imBEERialism

Recipe Details

| Batch Size | Boil Time | IBU | SRM | Est. OG | Est. FG | ABV |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5.2 gal | 60 min | 32.1 IBUs | 5.4 SRM | 1.054 | 1.013 | 5.4 % |

| Actuals | 1.054 | 1.01 | 5.8 % | |||

Fermentables

| Name | Amount | % |

|---|---|---|

| Lamonta American-style Pale Malt (Mecca Grade) | 10 lbs | 95.24 |

| Metolius Munich-style Malt (Mecca Grade) | 8 oz | 4.76 |

Hops

| Name | Amount | Time | Use | Form | Alpha % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fuggles | 30 g | 60 min | First Wort | Pellet | 4.9 |

| Fuggles | 20 g | 25 min | Boil | Pellet | 4.9 |

| Fuggles | 20 g | 5 min | Boil | Pellet | 4.9 |

Yeast

| Name | Lab | Attenuation | Temperature |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pub (A09) | Imperial Yeast | 72% | 64°F - 70°F |

Notes

| Water Profile: Ca 69 | Mg 1 | Na 10 | SO4 97 | Cl 49 |

Download

| Download this recipe's BeerXML file |

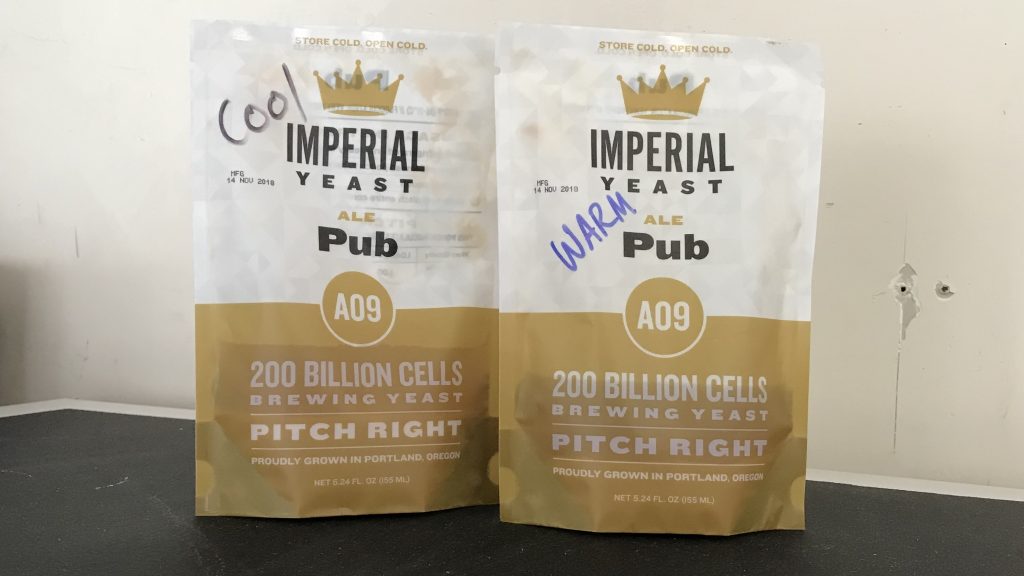

I received a box of yeast from Imperial the first week of December and immediately placed all of the pouches, which were still very cool, in my refrigerator. On December 13, after settling on the variable with Casey, I removed a package of Imperial Yeast A09 Pub and placed it on the counter in my laundry room. While we keep our heater set to 68°F/20°C during the winter months, this particular room is often a few degrees warmer due to the dryer being run most days.

Over the course of the following 13 days, I gave the pouch of yeast an abusive shake every time I walked by it, which had to have been at least 30 times, my goal being to somewhat emulate the bumps that occur during the shipping process. After filtering 2 sets of the same volume of water the night before brewing, I weighed out and milled the grain.

Casey arrived early the following morning, at which point I’d already begun heating the water. When strike temperature on either batch was reached, Casey dropped the bag of grains in and gave them a gentle stir to break up any dough balls.

Separating the start of each mash by 15 minutes, it was confirming to see both settled at the same target temperature.

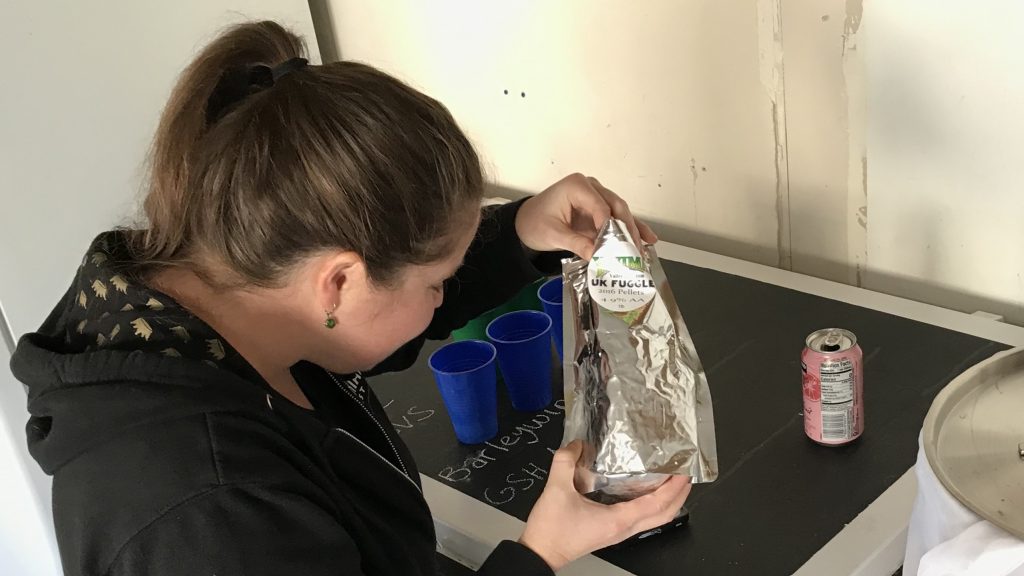

Casey then moved on to weighing out the kettle hop additions for both batches.

As the mashes rested, I pulled the cold stored yeast out of the fridge to give it some time to warm up prior to pitching, a standard step in my brewing process.

Following each 60 minute mash rest, the grains were removed and the worts were brought to a rolling boil, during which hops were added as stated in the recipe.

When the 60 minute boils were completed, the worts were quickly chilled to 66°F/19°C, our desired fermentation temperature.

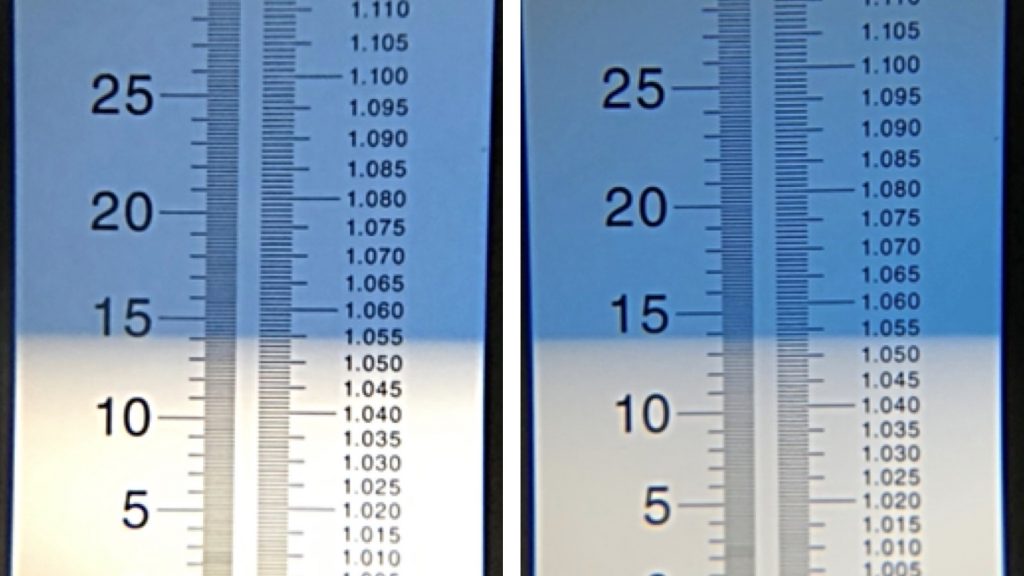

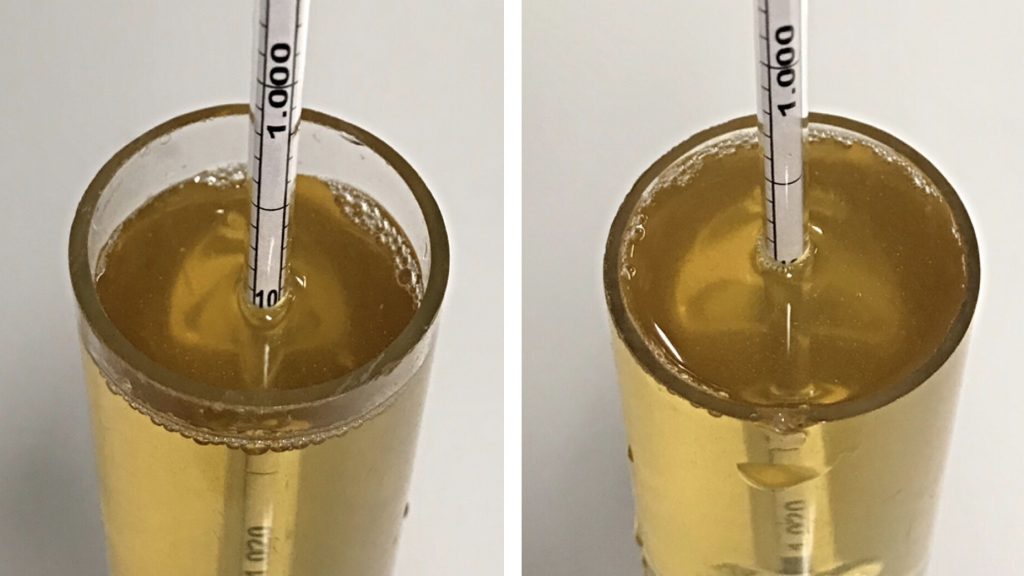

Refractometer readings showed the worts had reached a similar OG, with one clocking in ever so slightly lower than the other.

After 10 minutes of settling time, Casey transferred the worts to sanitized Brew Buckets.

The filled fermentors were placed in my chamber controlled to 66°F/19°C and each was pitched with its respective pouch of yeast.

Airlock activity was observed in both batches just 6 hours after yeast pitch, and they proceeded along with similar activity for the following 2 weeks, at which point neither was showing signs of fermentation. I raised the temperature of the chamber to 70°/21°C for a diacetyl rest and came back 4 days later to take hydrometer measurements showing both had reached the same FG.

At this point, I swapped out the airlocks for CO2 filled BrüLoonLocks and dropped the temperature in the chamber to 34°F/1°C for cold crashing.

Through consultation with Casey, we decided to skip fining these beers with gelatin, so I let them sit a little longer than I usually would to encourage particulate to drop out. After 4 days, I proceeded with kegging.

The filled kegs were placed in my cool keezer and burst carbonated overnight before I reduced the gas to serving pressure. After a week of conditioning, the beers were ready to serve to participants.

| RESULTS |

A total of 23 people of varying levels of experience participated in this xBmt. Each participant was served 2 samples of the beer fermented with yeast stored cold and 1 sample of the beer fermented yeast stored warm in different colored opaque cups then asked to identify the unique sample. A total of 12 tasters (p<0.05) would have had to accurately identify the unique sample in order to reach statistical significance, which is exactly how many did (p=0.048), indicating participants in this xBmt were able to reliably distinguish a British Golden Ale fermented with yeast stored cold from one fermented with yeast that was stored warm.

The 12 participants who made the accurate selection on the triangle test were instructed to complete a brief preference survey comparing only the beers that were different. A total of 3 tasters reported preferring the beer made with yeast stored cool, 8 liked the beer made with yeast stored warm, and 1 person reported perceiving no difference.

My Impressions: I began tasting these beers side-by-side the day after they were kegged and, unlike many xBmts, I thought they tasted identical. Unique in their Fuggle character with a nice toasty finish. Given the importance many place on keeping yeast cold, I wanted to ensure I gave this one a fair shake and performed 14 semi-blind triangle tests, out of which I chose the odd-beer-our 9 times. While this is fairly consistent, I have to say it was not easy at all. In fact, I found aroma to be the only place I noticed any difference, with the warm stored yeast beer having what I can only describe as a slightly sharper smell. The flavor and mouthfeel were identical to me, and I certainly didn’t pick up anything I would associate with autolysis.

| DISCUSSION |

One thing we know to be true is that warmer temperatures increase the rate at which certain reactions occur, and given yeast is a living organism, this matters equally as much prior to being pitched as it does during fermentation. Storing yeast cool leads to slower consumption of the glycogen reserves necessary for healthy cell walls, which can become thin when yeast is stored warm, leading to ruptured cells during fermentation that cause off-flavors. Indeed, tasters in this xBmt were capable of telling apart a beer fermented with yeast stored cool from one fermented with yeast stored warm, suggesting storage temperature can have a perceptible impact.

In addition to the effect on flavor and aroma, another reason it’s recommended to store yeast cold has to do with performance. Considering the hastened reaction rate that comes with warmer temperatures, it makes sense the yeast pouch that sat in my warm laundry room for 2 weeks would be less viable at pitch than the yeast that stayed in the fridge, which would presumably result in longer lag, less active fermentation, and potential attenuation issues. Interestingly, this wasn’t the case at all, both beers showed signs of activity at the same time, fermented vigorously, and finished at the same FG.

I’m in the admittedly fortunate position of being able to order yeast directly from Imperial Yeast, who ship next day with plenty of ice, so I’m able to get it in my fridge before it warms up. Based on my experience with these beers, and the fact I have a fridge with a dedicated yeast space, I certainly have no plans to store mine warm. However, if I were to order yeast in the middle of summer and the ice pack happened to melt during the 3 day shipping process, I wouldn’t be terribly concerned, probably toss it in a starter to ensure it’s alive and roll with it.

Unfortunately, Casey was back in Portland when these beers were ready and was unable to try them for herself, but I did ask if she’d share her thoughts on this xBmt:

I had a great time hanging out and making beer with Marshall! I’ll be honest, I really didn’t want this to work out. Storage temperature is so important for healthy yeast and successful fermentations. Ideally, yeast is stored in a fridge around 33-38°F/1-3°C and used as fresh as possible. If shipped from an online retailer, it’s paramount to buy ice packs and pay for expedited shipping.

We sent Marshall two packs of A09 Pub that were packaged on the same date, one stored warm for 2 weeks while the other stayed in the fridge. They were pitched at the same time and in a matter of hours both were fermenting. As you can imagine, this was both frustrating and also kind of awesome. While it’s great the warm stored Pub started fermenting around the same time as the properly/cold stored pack, a testament to the high cell count, viability, and quality of Imperial Yeast, we’ll be sticking to recommending people store yeast in ideal conditions.

If you have any thoughts about this xBmt, please do not hesitate to share in the comments section below!

Support Brülosophy In Style!

All designs are available in various colors and sizes on Amazon!

Follow Brülosophy on:

FACEBOOK | TWITTER | INSTAGRAM

If you enjoy this stuff and feel compelled to support Brulosophy.com, please check out the Support page for details on how you can very easily do so. Thanks!

23 thoughts on “exBEERiment | Impact Yeast Storage Temperature Has On British Golden Ale”

Which sample/s did the 12 correct participants like?

Not sure how that paragraph got deleted, but the article has been updated.

Great article, Marshall. I would love to see this same exact experiment with dry yeast. Specifically, two packs of (for example) US-05 that are several months old with one having been kept in a refrigerator the whole time and the other stored at room temperature. This idea comes to mind because I’ve noticed that not all brick and mortar homebrew supply shops store dry yeast in a cooler. Not terribly common, but when I see it I immediately feel hesitant to buy that yeast.

Just a thought, and I may try doing this experiment myself at some point. Thanks again for doing this experiment with Imperial. Great info, as always.

Agreed. I also notice some suppliers have the dry yeast on the shelf and not refrigerated.

While I store all my dry yeast in the fridge, the durability of dry yeast is quite a bit higher than liquid. If you notice bread yeast is not stored refrigerated. I make a lot of bread and buy yeast in multi pound packs. I store the unopened packages as the store does and once opened I move it to the fridge.

That said I would probably buy from a LHBS that refrigerated their dry yeast. When you could pick up a packet for a couple of bucks it was easy to keep some extras around but dry prices have gone way up in the last 5-6 years and I want to see a little more care in storage.

FWIW, I recently made an IPA with two packs of US-05 that were three YEARS past their Best By date. Still fermented fine and the final beer was great! Currently fermenting another IPA now with a single pack of US-05 dated 2/2021, but I made a starter with it first (as an experiment) and because the OG was 1.060.

Good on ye for using Fuggles. I love Fuggles in classic Ale recipes.

Cool, so i dont need to use that big fridge at work anymore? Would save us a lot of $$

I’m certainly not recommending that… and I’ll certainly be storing my yeast cool.

I wonder if imperials 200 billion cell count was a factor. I’d be interested to see if the results would be the same for white labs or wyeast

I’d be interested to see if the freshness had something to do with it. Assuming that a direct shipped yeast should be much closer to the manufactured date, instead of being closer to the use by date.

Perhaps because the pitches were so fresh (and with a high cell count), the warm storage didn’t have as much as an effect. I wonder if the pitches were closer to the use by date if the preferences would remain the same.

Pretty crazy that people tended to prefer the warm storage beer!

maybe a slight underpitch added to the flavor of the beer for some people? more esters or something? interesting.

Great exbeeriment! How did you like the Pub stand? I’ve always been a big fan of WLP002 and would like to give Pub a try. On Imperial’s site they mention lots of esters but wondering if you keep the temp cool to begin if it keeps it in check.

Also, out of curiosity why do you always list grains in lbs and oz but hops in grams?

I’ve used it plenty, it’s fantastic, one of my favorites.

I do the same. I weigh grains in pounds & ounces while hop pellets are weighed in grams because I use a lot of grains and just a little bit of hops in terms of volume. Plus it’s easier to measure the difference between, say, 25 and 40 grams of hops versus 0.881849 and 1.41096 ounces.

Pretty cool this came back as significant and even though “more people preffered the warm storage yeast” beer really this just shows that there is a difference and to get consistent results you should store them consistently. I don’t think Casey should be worried at all :-p I’ll keep spending as much attention on keeping my yeast cool as I have been thanks to this experiment, thanks!

I always love the exbeeriments but this would have been an easy one to bring some analytical data to the table via a methylene blue viability count. Despite the temperature difference, the yeast packs could (theoretically) have identical viability. I’d love to see a viability regression curve from the guys at Imperial prior to trying to replicate this Exbeeriment.

The timing of your post is remarkable because I just had an unintended yeast storage temperature experiment…in the opposite temperature direction. Last week, I picked up ingredients at my LHBS for a NE IPA that I planned to brew on Sunday. My ingredients included a pouch of Imperial Juice Yeast. The next day, I found the yeast package in my FREEZER. I must’ve had a brain fart when I was unpacking the ingredients after coming home from the LHBS. I wrote to Jessica at Imperial Yeast, told her what happened, and asked “Did I destroy the yeast!?!?!”

Her reply:”Possibly. You’ll be looking at a decreased cell count for sure, so plan on making a starter. In our experiments with thawed frozen yeast there were still some viable cells, so I think although your cell count has been dramatically decreased, you will be able to prop this up for your beer by Sunday. You’ll want a 2L starter if you have a stir plate and a 4L starter without one. Please let me know if you want further instructions on making a starter. Good luck and let us know how it turns out!”

I’m pleased to report that the starter showed signs of great vitality, developing a healthy krausen. I brewed, cooled and pitched the yeast. Within hours, I had an active fermentation underway.

I never cease to be amazed at house robust yeast can be. Cheers.

Jessica is great, and I’m glad your yeast worked out!

Funny timing on this exbeeriment, as I just received some Imperial L17 yeast that spent about 5 days in transit in warm-ish Midwest weather, arriving with a room temperature ice pack shipped from that home brew shop owned by the big boys of American beer.

Packaged in April, I’m not too happy that it took 5 days when I split the shipment thinking that the yeast itself would arrive faster, but alas the grains and hops arrived last Friday.

Ultimately, after reading this exbeeriment, I’m not worried. Making a warm fermented lager for a summer party and I’m sure after making a starter it will be fantastic.

I was just listening to the episode on yeast storage temperature and was surprised when Casey said that if someone left their yeast in the laundry room for 4 days she would advise them not to pitch it or even make a starter. The reason this particularly struck me is that I’m in the middle of stepping up a mixed culture from my favorite brewery (Jester King). I’ve taken the dregs from 4 bottles of Le Petit Prince which were bottled about 2 months ago and I know they have not been stored at cold temperatures until I put them in my fridge about 2 weeks ago. I’m successfully cultivating the yeast and bacteria in the 2nd starter beer now and everything seems great so far, i.e. no aromas or taste of autolysis or off flavors in the starter beer (though the mixed culture is funky to begin with). Surely the viability and cell count of the yeast I’m using for this starter is less than a manufactured yeast packet that has been left at room temperature for a few days.

So I’m curious to know why Casey wouldn’t even recommend making a starter with the slightly “aged” yeast? After all, I thought that’s what starters were for: to grow new, viable yeast from a source that has potentially lost some of those qualities between manufacturing and primary fermentation. Maybe it’s a question better suited for Casey since it’s her advice but I’m wondering if you can shed any light on this conundrum for me.

Finding this article in perfect timing for me. I have listened to all your podcasts over the last few months when I got back into brewing. Did not realize you did a study on this and I have been trying to get an opinion on this from a reliable source and not just arbitrary FB posts.

Due to the Coronavirus I ordered supplies and White labs yeast (nonoffense to your sponsor. FWIW I have a hard time finding it locally ). It got shipped and it took about a week to 9 days for me to get the yeast. I didn’t have it shipped in ice because this time of year and I live in northeast and it usually only takes 2-3 days to receive. Well it was delayed and was wondering if it was worth pitching. It is the wlp001 and looks a little tinge of brown color ao I was nervous. I usually pitch 2 packs anyway so I will give it a try.

Thanks and keep up the good work.