Author: Marshall Schott

Fermentation is the seemingly magical, though entirely scientifically explainable, process that turns the wort brewers make into delicious beer. The microorganism responsible for this wonderful conversion is yeast, a single celled fungi that, like all living organisms, work better when provided an optimal environment.

Brewers have adopted various strategies to ensure their yeast are well taken care of including propagation in starters and precisely controlling the temperature throughout fermentation. Another common method said to further reduce the risk of problematic fermentations involves the use of yeast nutrient, a common one of which is produced by Wyeast, who makes the following claim:

A wort that is nutrient-deficient, or which has adequate nutrients but limited bioavailability to the cells, can experience inhibited yeast growth, disrupted or incomplete fermentations, inconsistent attenuation rates from batch to batch, and diminished cell viability.

I’m aware of brewers who use such nutrients as a matter of course, some who dose each batch of beer they make as a better-safe-than-sorry measure, while others contend it has some positive impact on fermentation and even finished beer quality. In the nearly 15 years I’ve been brewing, I’ve never once used yeast nutrient, as I never saw a need. However, after dosing a recent batch of hard cider with nutrient and noticing a fairly drastic reduction in lag, I became curious as to the impact it might have on beer and put it to the test!

| PURPOSE |

To evaluate the differences between a beer produced using yeast nutrient and the same beer that received no yeast nutrient.

| METHODS |

In the hopes of creating a relatively stressful fermentation environment, I opted to brew a cool fermented lager that was direct pitched and went with an adapted version of my May The Schwarzbier With You recipe.

Kräftig

Recipe Details

| Batch Size | Boil Time | IBU | SRM | Est. OG | Est. FG | ABV |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5.5 gal | 60 min | 26.3 IBUs | 26.1 SRM | 1.053 | 1.014 | 5.2 % |

| Actuals | 1.053 | 1.012 | 5.4 % | |||

Fermentables

| Name | Amount | % |

|---|---|---|

| Lamonta American-style Pale Malt (Mecca Grade) | 4 lbs | 36.78 |

| Pelton Pilsner-style Malt (Mecca Grade) | 3.75 lbs | 34.48 |

| Metolius Munich-style Malt (Mecca Grade) | 2 lbs | 18.39 |

| Gladfield Light Chocolate Malt | 12 oz | 6.9 |

| Caramel/Crystal Malt - 15L | 6 oz | 3.45 |

Hops

| Name | Amount | Time | Use | Form | Alpha % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Horizon | 11 g | 60 min | First Wort | Pellet | 14.1 |

| Tettnang | 31 g | 15 min | Boil | Pellet | 3.5 |

Yeast

| Name | Lab | Attenuation | Temperature |

|---|---|---|---|

| Harvest (L17) | Imperial Yeast | 72% | 50°F - 60°F |

Notes

| Water Profile: Ca 71 | Mg 1 | Na 10 | SO4 100 | Cl 50 |

Download

| Download this recipe's BeerXML file |

I prepared for this 10 gallon no sparge brew by collecting the full volume of filtered water in my mash tun a day ahead of time.

With the water collected, I weighed out and milled the grain.

I placed my heat stick in the water and set the timer to turn on a couple hours before I started brewing the next day.

The next morning, I was greeted with perfectly heated strike water, into which I incorporated the grains using my large doughball buster.

A check of the mash temperature showed I was close enough to my 152°F/67°C target.

I let the mash rest for 60 minutes, gently stirring periodically to improve efficiency, after which I collected the sweet wort in my trusty graduated bucket.

After transferring the wort to my kettle, I brought it up to a boil and added hops per the recipe.

At the completion of the 60 minute boil, I quickly chilled the wort to slightly warmer than my groundwater temperature.

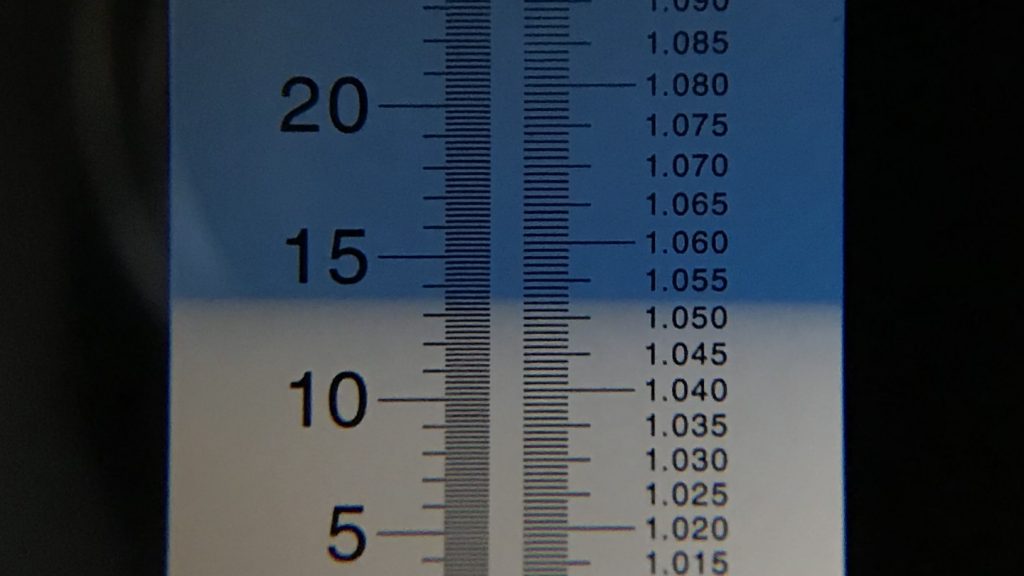

A refractometer reading showed the wort was smack on my target OG.

Equal amounts of wort were racked to separate sanitized Brew Buckets.

The filled fermentors were placed in my chamber to finish chilling, the wort at this point was 74°F/23°C. I then proceeded with preparing the yeast nutrient for one batch per the recommended method of dissolving a measured amount of the powdery substance in hot water. To keep things as equal as possible between the batches, I added an identical amount of hot water sans nutrient to the other batch.

I left the worts alone for a few hours to finish chilling before returning to direct pitch a single pack of Imperial Yeast L17 Harvest into each batch.

The following morning, approximately 12 hours post-pitch, I noticed airlock activity in both batches, indicating minimal difference in lag. I let the beers ferment at 55°F/13°C while I vacationed with my family and opted to skip any temperature increases.

With neither beer showing signs of fermentation activity after 15 days, I took hydrometer measurements indicating both had achieved the exact same FG.

I replaced the airlocks with CO2 filled BrüLoonLocks before reducing the temperature in my chamber to 32°F/0°C for cold crashing.

Curious if yeast nutrient might have an impact on appearance, I decided to skip my regular gelatin fining process and kegged the beers after 2 days. The filled kegs were placed in my keezer, burst carbonated, and left to lager for 2 weeks before they were ready to serve to tasters.

| RESULTS |

A total of 21 people of varying levels of experience participated in this xBmt. Each participant was served 2 samples of the beer made without yeast nutrient and 1 sample of the beer made with yeast nutrient in different colored opaque cups then asked to identify the unique sample. At this sample size, 12 tasters (p<0.05) would have had to identify the unique sample in order to reach statistical significance, though only 8 (p=0.40) made the accurate selection, indicating participants in this xBmt were unable to reliably distinguish a Schwarzbier made using yeast nutrient from one made without the use of yeast nutrient.

My Impressions: As usual, I began sampling these soon after getting them carbonated and, even in my non-blind side-by-side evaluations, I was unable to tell them apart. Needless to say, my performance on semi-blind triangle tests was completely inconsistent, I guessed the odd-beer-out in 2 out of 7 attempts. As for the beer, I’ve got to say, this Schwarzbier hit the goddamn spot! Even after all these years, I continue to be reminded that simplification of recipes often results in good outcomes, which is certainly the case for this slightly adapted version of a beer I’ve made many times before.

| DISCUSSION |

It makes sense that by supplying yeast with nutrients, they’ll perform better during fermentation in a way that could ultimately have a positive impact on the finished beer. This seems even more plausible when the yeast is forced to work in relatively stressful conditions, such as those caused by a cool fermentation temperature and pitching direct without propagation in a starter. Interestingly, not only were blind participants unable to reliably tell apart a cool fermented Schwarzbier made with yeast nutrient from one made without nutrient, but no differences in fermentation were observed either, suggesting the yeast nutrient had little if any impact on the beer.

Considering the hundreds of batches of good beer I’ve made without yeast nutrient, these results did little to convince me to change my current practices. However, as easy as it’d be for me to write-off the potential benefits of using yeast nutrient altogether, I’m not quite ready make that leap. Not only did this xBmt focus on one specific brand of yeast nutrient, of which there are many, but the lack of a perceptible difference may not necessarily be a function of the yeast nutrient. For example, the yeast used to ferment both beers was very fresh, which could have mitigated the need for nutrients despite the somewhat stressful environment.

Overall, while I may not integrate yeast nutrient into my standard brewing routine, I can understand why some might opt to use it regularly purely as a way to help protect against problematic fermentations. Given the reduced lag time I observed when I used nutrient in a recent batch of hard cider, it’s clear to me it does something, and I look forward to seeing the impact it has when used in even more stressful conditions such as a high OG beer.

If you have any thoughts about this xBmt, please do not hesitate to share in the comments section below!

Support Brülosophy In Style!

All designs are available in various colors and sizes on Amazon!

Follow Brülosophy on:

FACEBOOK | TWITTER | INSTAGRAM

If you enjoy this stuff and feel compelled to support Brulosophy.com, please check out the Support page for details on how you can very easily do so. Thanks!

38 thoughts on “exBEERiment | Impact Yeast Nutrient Has On Schwarzbier”

I love these exBEERiments! I liked this one as I am always looking for ways to refine my process and habits. I use yeast nutrient on every batch, but have never tried them side by side. My understanding is that Inperial Yeast is almost always among the freshest yeast you can buy. I feel like yeast nutrient is always good, but the effect may be more noticeable on a beer fermented with older yeast. It is common to find white labs and wyeast aged 2 to 3 months on the date of purchase. Maybe try the same exbeeriment with older yeast and see if there is a perceived difference. Nobody likes wasting batches, but that may yield the result you initially wondered about

Love your work here!

I seldom use nutrient, but am tempted on big beers as you mention at the end of article.

Generally my brews get off to quick healthy starts with out nutrients, and often lack for headspace – which the nutrient exacerbates.

I tend to pitch stir and split into a pair of three gallon fermentation’s to get past blowoff phase.

Not to be critical, but I believe Wyeast recommends rehydration then adding toward end of brew…

Tony LeClair

I think I would have removed the hotbreak, trub (these get removed by the big guys I think) etc. for less yeast nutrients. I’ve seen that some breweries remove the hotbreak because they contain stalling/oxidating agents but since the hotbreak also contains yeast nutrients they add back the nutrients.

This is consistent with my adventures in yeast starters, too. I have nutrient but only remember to add it about half the time and I’ve noticed zero difference in lag time with fresh or salvaged yeast.

if you use RO water and then modify water profile, does that affect the nutrients that yeast consume?

That won’t affect what the yeast consume, but it will affect your enzymatic processes during your mash, which indirectly affects what the yeast can do in fermentation

Using RO water and modifying your water profile is meant to encourage good enzymatic activity during mashing as well as adjust your flavor profile between malt sweetness and bitterness. Indirectly this can affect how much your yeast is able to ferment due to the fermentability of the wort, but it won’t affect the nutrients the yeast consumes.

Yes, it can.

Maybe it doesn’t matter, but don’t the instructions direct nutrient to be added the last 10-15 minutes of the boil?

They do suggest adding later in the boil, but I believe that is only to ensure the addition is sterilized. I am unaware of any break down of nutrients from having it in the boil longer than that, but it could be something worth checking out!

Yeast nutrient is primarily about yeast assimilable nigrogen. When making cider and mead you’re low in nitrogen requirements. I would think that brewing grains would help to release plant based nitrogen in to the wort thus creating a more favorable environment for the yeast. I’m not sure if extract brews would be different because I mainly make mead and wine.

Good article though since ImI considering taking up beer brewing soon.

I think using yeast nutrient comes from Brewers who have heard just a little about wine and Mead making, but not enough to really understand…. Fruit and honey are low in nitrogen and phosphorus and need a supplement in order to handle the massive growth to consume all that sugar without producing some very nasty sulfur aromas.

A common supplement for yeast starters besides good old DAP is (wait for it!) Malt! Yes, good old malt for beer making. Grain is high in both nitrogen and phosphorus.

I am totally unshocked at the results of this one 🙂

Chris

Just bought yeast nutrient recently (it literally arrived two days ago) because I’m going to brew a Brut IPA and according to Kim Sturdivant:

“Lastly, it is very important to add nutrient to the boil as well as 1/2 way through fermentation (with something like BSG’s Startup) since the wort will be almost entirely glucose, there is not a lot of nutrition for the yeast.”

I’ve never used it before, but in this case it made sense. Curious if your results would have been different in a more stressful environment with either A) less yeast nutrients naturally in the wort or B) a higher-alcohol brew.

I can attest to things being different in a more stressful environment. I do 2 additions on my beers over 8% ABV. One addition in the boil and another a day after fermentation kicks off. I also add additional O2. I add nutrient to all of my batches anyway though, even low gravity. The main reason is this helps to encourage healthy yeast metabolism throughout, and if you like to wash and re-use yeast, you want to make sure you’re re-pitching healthy yeast.

I’m planning a brut IPA in the future as well and just read that article. I had the same question about nutrient. I haven’t really been able to find much information on brut as I would like. So I just planned on making sure I over pitched somewhat to make up for all the fermentable sin the wort.

I recently did back to back batches of equal OG beers (1.040), very similar recipes, using dry yeast (BE-134) sprinkled on the top, no starter. The first batch had no yeast nutrient (“energizer”) added and took 12 hours to get going. The second batch with the yeast starter started going at 6 hours. I think the Imperial Yeasts may already have more yeast nutrients built in to the liquid pack than the emulsifiers that are present in the dry yeast. Not sure, but this is just what I saw last week. I never use yeast nutrient with Imperial Yeast. They kick off quickly and I rarely make a starter with them. I don’t usually brew beers >1.065). Thanks for sharing this xBmt! -Cheers

All liquid yeasts are more or less the same. Literally. Freshness is a different issue, but a pack of Imperial vs. Wyeast vs White Labs will all behave similarly, if not the same, if they are of the same age. I totally see how nutrient might help a dry yeast since those buggers are effectively in suspended animation and you didn’t exactly help them by not rehydrating in water first. 🙂 If you were dessicated for months I’d guess the extra nutrients would help wake you up quicker. I’ve used nutrient basically in every batch I’ve ever done but I would guess doing a vitality starter has more benefit than adding yeast nutrient.

It’s true that all liquid yeast is likely sourced from the same place. However, the mother cells that the yeast are propagated from have a drastic effect on the health and viability of the ensuing yeast. Imperial organic propagates, packages, and ships within 48 hrs and keeps temp during shipment. This allows not only more viable yeast in each package, but fresher yeast when it arrives. I have favorite strains from white labs and wyeast, but no maker right now can compete with imperial yeast health and viability. And by viability, I mean more than just living yeast, I’m referring to healthy yeast propagated with minimal mutated cells for a more reliable and repeatable finished product. And no… i don’t work for imperial, i just had the opportunity to attend seminars on all 3 of the big liquid yeast manufacturers to compare 🙂.

I’ve never had more consistent results as I have with Imperial.

My understanding of yeast nutrient is that it’s typically used for high adjunct beers when there may be a relatively low amount of the naturally occurring Nutrients in wort.

Based on all the recent findings at the homebrew scale, yeast nutrient seems a lot like oxygenation to me — you can probably make the same beer without it most of the time. In my mind, it’s cheap insurance in the event that your yeast aren’t in tip-top shape.

With that in mind, I only end up using nutrient when re-pitching. I’ve forgotten before and haven’t noticed much of a difference, but it’s cheap insurance when I’m reusing the cake of a lower gravity beer and putting it through a second or third fermentation in a higher gravity beer.

I’ll also say that just smelling the stuff will give you pause. And back when I was adding yeast nutrient in my starters, there was definitely a flavor impact when tasting the starter wort. At the 5 gallon scale, it’s probably undetectable, but I hate adding things to my beer that I wouldn’t want to eat or drink.

Another interesting article! I look forward to more xbrmts with this topic. Looking online at the different nutrients ingredients, it would seem most worts would provide adequate amounts. Definitely could be a different story with old, highly stressed yeast or maybe a high adjunct wort though. Can’t wait.

Thanks for the exbrmt. Every time I do a starter or just a regular mash, I look directly at my container of yeast nutrient and say to myself, “I should add that this time.” It hasn’t moved off my shelf in over a year.

A really interesting experiment. My experiences with yeast nutrient are pretty limited and under quite different conditions as I brew under pressure and at higher temperatures but I did find that it can speed up the ferment by having the ferment finish better, more complete with less lag time.

I didn’t notice any variation in taste but wasn’t making two beers at a time.

When I get a chance I will do a more comprehensive trial and report back.

Did your yeast nutrient contain zinc (such as zinc sulfate)? Zinc is a vital yeast nutrient that is not present in RO or distilled water, or (to my knowledge) in barley malts. Most yeast nutrients do not contain zinc. Only a small amount of zinc is actually required. Above a rather low threshold it can actually begin to be tasted.

It is my belief that these nutrients allow a shorter lead time between pitch and active fermentation, and, may promote a more active ferment. Wouldn’t the test have been more informative if the specific gravity had been recorded daily in order to see if the nutrients actually promoted increased activity? Allowing both samples to simply ferment out for two weeks without tracking progress does not really test anything regarding performance. I guess it’s good to know it does not affect flavor, so the test was not a total loss, but it could have bore more results.

I sincerely appreciate what you guys do. My suggestion focuses on general experiment design. I think that you are on to something when you write “In the hopes of creating a relatively stressful fermentation environment…” If you really want to determine the role that these variables play in the beer making process it might be helpful to establish a baseline that is “not very good beer” and then test variables that turn it into “good beer.” Currently you have conditions that are already at the “good beer” stage and then you see no difference when you change something. Such results aren’t very useful when the goal is to determine what the variable does and if it is essential or not and any conclusion that “this variable doesn’t matter” is probably spurious. My point is, if you want to determine how yeast nutrient can affect the brewing process, you need to start with conditions where the yeast is quite sickly and lacking in nutrients. When your background is conditions that are quite good for yeast, the surprising aspect with your results is that you are surprised that you didn’t see any difference…it should have been obvious that you wouldn’t see a difference. Moreover, these experimental problems pervade many of the exbeeriments that you guys design. Think of it as a signal to noise issue…the way you designed the experiment you can only expect very subtle differences that your detection method has a hard time detecting because you are near the maximum range of your detector.

I have often heard it said that yeast nutrients is not for this batch, it is for the next.

I can’t say I can put my finger on any difference yeast nutrient has made but, as has been mentioned, it’s cheap insurance in a regular batch. This was an interesting read, for sure, but I’m actually more interested in what it does in a starter where you’re trying to make as much viable yeast as possible with, most likely, less than optimal yeast in an environment that isn’t very good for very long. I might do a side by side with two starters using a split smack pack and see if I end up with more and/or healthier yeast in either flask.

If you want to use a yeast nutrient and want a free alternative then you can add some surplus yeast from a previous brew to the boil. This will obviously kill the yeast but it will release it nutrients for subsequent consumption by your pitched yeast. This is a practice that has been used by some British brewers.

Servomyces is an expensive method of doing exactly this: http://www.lallemandbrewing.com/product-details/servomyces-d50/

I think a good experiment would be yeast nutrient and no trub vs high trub beer.

Yes!

I wonder how this would have turned out using dry yeast that is close to its use by date, sprinkled into the fermenter, without rehydrating?

I’d love to see a repeat study on yeast nutrients doing apple cider. In traditional beer the yeast have a lot of nutrients from the grains and so adding yeast nutrients is unnecessary. In apple cider however, there is a huge lack of nutrients. The apple cider wort is just pure simple sugars with little available nitrogen or other nutrients.

If the experiment was to see if the yeast nutrient gave it a jump start, shouldn’t gravity readings been taken periodically? Perhaps the yeast nutrient added beer finished quicker?

I just came across this, but it is well known that barley malt has many of the essential nutrients needed for yeast metabolism. To do a true test of the effects of yeast nutrient, you should start with a nutrient free wort. Maybe do a batch where the only fermentable is dissolved table sugar, flavor it with some hops, and pitch your yeast. At that point, if you’re tasters can’t tell the difference between the two batches, you can conclude that the yeast nutrient is not helping anything.

This suggestion is a better test. If the test were done using that or even a high adjunct beer, the results might have been more distinguishable.

I hear stumbled across this article right now and I am thoroughly impressed and honoured 😂. As one that practises the scientific method (clinical pharmacologist and researcher), I fully appreciated what you put into this experiment. Well done.