Author: Jake Huolihan

With some notable exceptions, brewers who package their beer in bottles generally prefer them to be amber in color because it blocks out more UV light, which interacts with isomerized hop compounds to produce 3-methylbut-2-ene-1-thiol (3-MBT). The telltale sign of a beer with higher levels of 3-MBT, as anyone who has drank from clear or green bottles likely knows, is a distinct skunk character, also known as lightstruck.

For the most part, lightstruck beer is an issue viewed as being packaging related, as the rest of the brewing process is largely free from exposure to light, especially on the commercial scale where fermentation tanks are usually made of stainless steel. However, some of the most commonly used fermentors by homebrewers are made of clear glass or plastic, materials that readily allow any environmental light to touch the beer. While fermentation chambers are a good option for avoiding light exposure, those who don’t have the luxury of such an enclosure are cautioned to keep their fermentor covered to avoid producing this off-flavor.

As someone who has used clear fermentation vessels extensively and started out by fermenting in a windowed basement, I’ve always been curious as to the effect exposure to sunlight during fermentation has on my beer. The mechanism for beer skunking is relatively well understood and accepted in the brewing community, though I was still curious if the methods I’ve employed to keep sunlight out of my fermenting beer were worth the effort.

| PURPOSE |

To evaluate the differences between a pale lager fermented in a clear vessel that was covered and the same beer fermented in a vessel exposed to regular sunlight.

| METHODS |

Since the vector for lightstruck flavor is the photodegradation of isomerized acids from hops, I went with a hoppy American Pilsner for this xBmt.

Pepe

Recipe Details

| Batch Size | Boil Time | IBU | SRM | Est. OG | Est. FG | ABV |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5.5 gal | 60 min | 45.0 IBUs | 3.3 SRM | 1.049 | 1.013 | 4.8 % |

| Actuals | 1.049 | 1.014 | 4.6 % | |||

Fermentables

| Name | Amount | % |

|---|---|---|

| Weyermann Pilsner Malt | 8.562 lbs | 85.09 |

| Weyermann Vienna | 1.5 lbs | 14.91 |

Hops

| Name | Amount | Time | Use | Form | Alpha % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hallertau Magnum | 6 g | 60 min | Boil | Pellet | 14 |

| Loral | 11 g | 30 min | Boil | Pellet | 10.3 |

| Perle | 11 g | 30 min | Boil | Pellet | 8 |

| Saphir | 11 g | 30 min | Boil | Pellet | 3.5 |

| Loral | 24 g | 5 min | Boil | Pellet | 10.3 |

| Perle | 24 g | 5 min | Boil | Pellet | 8 |

| Saphir | 24 g | 5 min | Boil | Pellet | 3.5 |

Yeast

| Name | Lab | Attenuation | Temperature |

|---|---|---|---|

| Global (L13) | Imperial Yeast | 75% | 46°F - 56°F |

Notes

| Water Profile: Ca 58 | Mg 0 | Na 8 | SO4 60 | Cl 61 |

Download

| Download this recipe's BeerXML file |

The night before brewing, I collected the full volume of water for a 10 gallon batch and adjusted it to my desired profile before milling the grains.

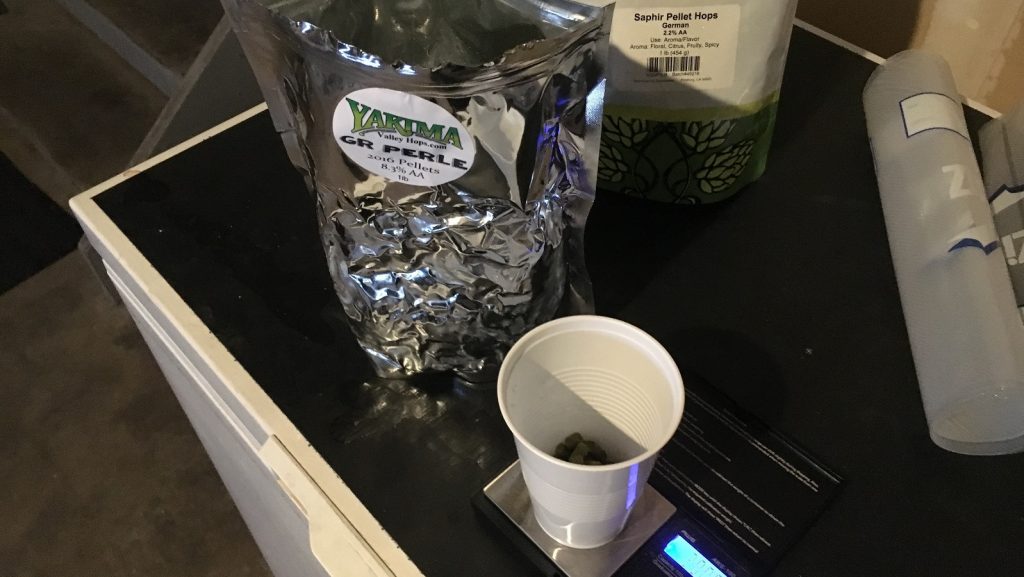

I started off the next morning by turning on the element to heat my strike water then proceeded to measure out the kettle hop additions.

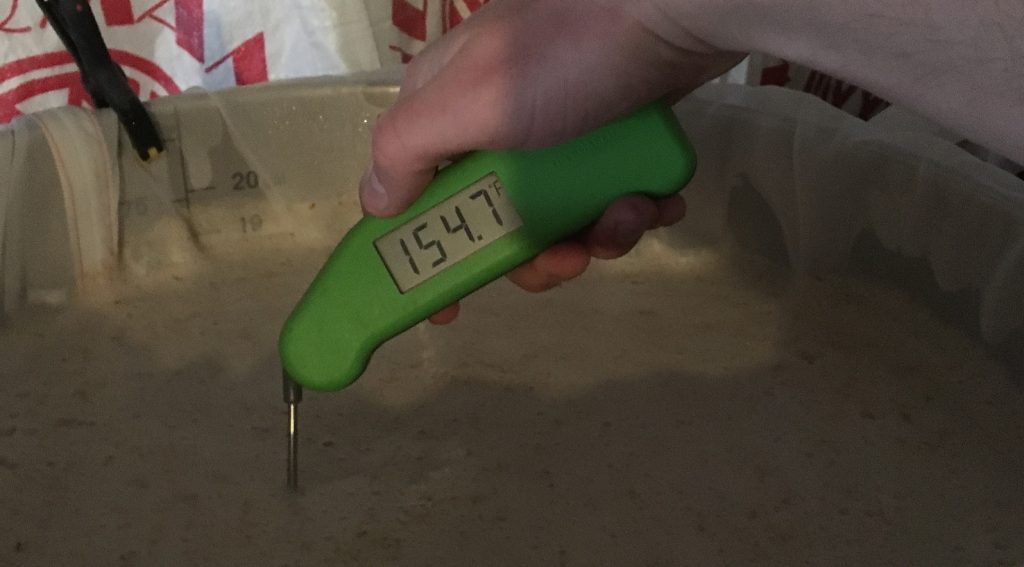

When the water was slightly overheated, I transferred it to my mash tun and allowed it to preheat for a few minutes. I was impatient and mashed in a little early, which led to a slightly higher than expected mash temperature. No biggie.

I returned every 15 minutes to briefly stir the mash over the course of an hour long rest.

I stole a small sample of wort to ensure the mash pH was where I expected it to be.

At the completion of the mash, I ran off the sweet wort to a kettle.

I turned the element on and added the first wort hop addition. Once the wort was boiling, I set a timer for 60 minutes and added hops at the times laid out in the recipe.

When the boil was finished, I hastily chilled the wort.

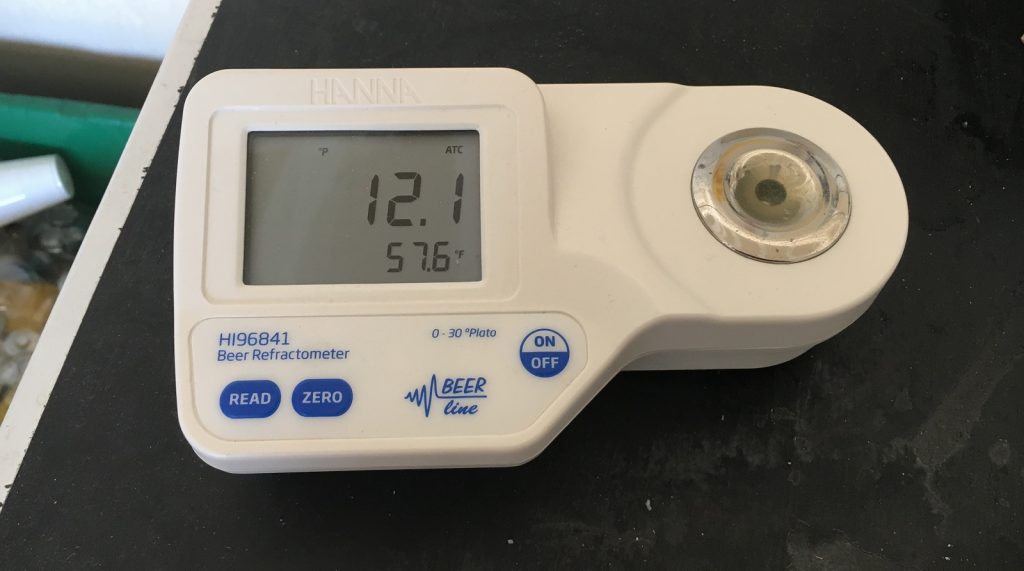

A refractometer reading showed my OG was spot on.

The wort was then evenly split between 2 identical fermentors.

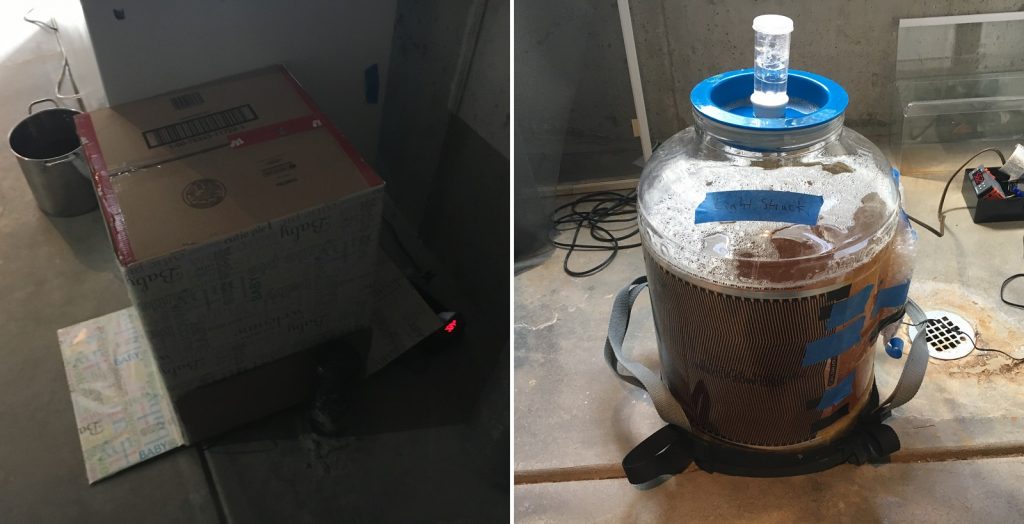

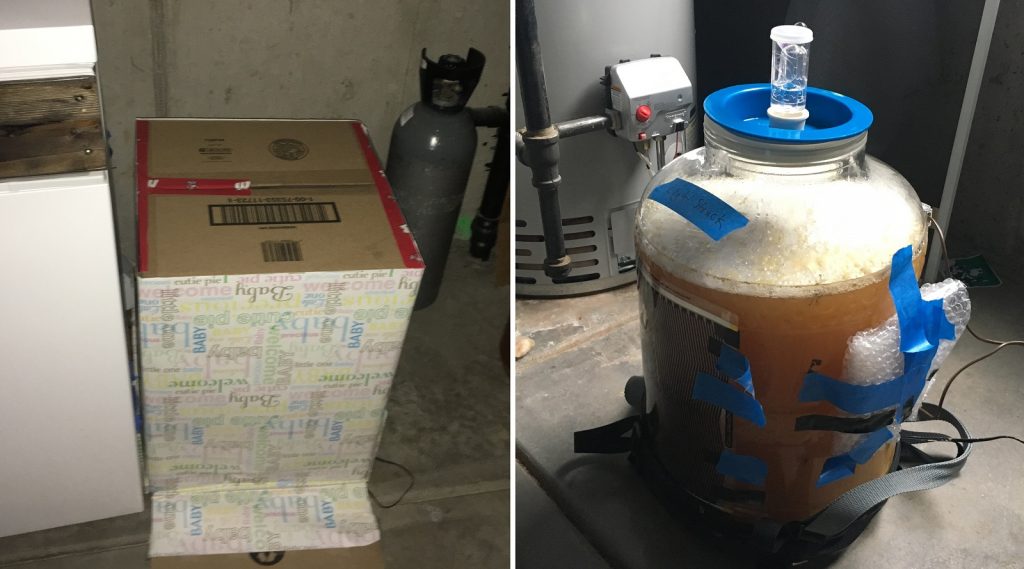

My Colorado basement stays fairly cool this time of year, so I decided to forgo fermenting in my chamber and instead controlled temperatures using heating pads since cooling wouldn’t be needed. One of the full carboys was immediately placed in a place that gets no direct sunlight and covered with a large box, while the other was placed next to a large window that receives direct sunlight about 8 hours per day. I began to experience a slight feeling of regret at this point.

Using leftover wort, I made vitality starters with Imperial Yeast L13 Global, pitching one into each batch after a 4 hour wait.

Controlling the beers to 66°F/19°C, I noticed airlock activity the following day with the uncovered carboy bathed gloriously in the rays of the morning sun, which is much closer in Denver than many places in America.

Signs of fermentation were absent after 5 days, so I took hydrometer measurements confirming both beers had reached FG.

Moving both carboys to an area free of direct sunlight so as to prevent UV exposure to the covered batch, I proceeded with kegging.

I skipped fining with gelatin and let the filled kegs lager on gas in my keezer for a couple weeks. When it came time to collect data, the beers were clear and nicely carbonated.

| RESULTS |

A total of 20 people of varying levels of experience participated in this xBmt. Each participant was served 1 sample of the beer fermented under cover and 2 samples of the beer fermented in direct sunlight in different colored opaque cups then asked to identify the unique sample. At this sample size, 11 tasters (p<0.05) would have had to identify the unique sample in order to reach statistical significance, which is exactly how many were able to do so (p=0.038), indicating participants in this xBmt could reliably distinguish a Pilsner fermented in a dark environment from one that was exposed to direct sunlight during fermentation.

The 11 participants who made the accurate selection on the triangle test were instructed to complete a brief preference survey comparing only the beers that were different. A total of 5 tasters reported preferring the beer fermented in the dark, 4 said they liked the beer fermented in direct sunlight more, and 2 tasters reported perceiving no difference.

My Impressions: During fermentation, I smelled a cannabis-like aroma from the lightstruck beer that was absent in its covered counterpart, which had me convinced they’d be different once finished. Sure enough, I was consistently able to tell the beers apart, correctly identifying the odd-beer-out in 8 out of 10 semi-blind triangle tests. Interestingly, the differences in aroma seemed to fade as the beers sat out, leaving me to rely more on taste and had me wondering if the lightstruck character had dissipated. As much as I enjoyed the version of this beer fermented under cover, it took everything in me not to dump the lightstruck batch before I finished collecting data. Yuck!

| DISCUSSION |

A simple task: pour yourself a glass of pale beer, something cheap and evil is fine, or a tasty homebrew works just as well. After taking a refreshing sip, place the glass of beer in direct sunlight and start a timer for 45 seconds. While waiting for the timer to beep, pour a similar amount of the same beer into another glass, except leave this one out of the sun. When the timer goes off, grab your sunbathed beer and sample it next to the other sample. Smell and taste a difference?

Skunking is real. Through both organoleptic sensory evaluation as well as objective lab analysis, we know that UV exposure produces perceptibly high levels of 3-MBT in beer dosed with hops, hence some larger breweries rely on hop extracts to circumvent this risk. While the most commonly discussed vector for UV exposure is packaging, the fact tasters in this xBmt were able to tell apart beers fermented in either a dark environment or in direct sunlight validates the concern that lightstruck character can develop during fermentation.

Given my personal experience with these beers, I was surprised more people weren’t able to tell them apart, as the skunk aroma known to be present in green bottled quaffers was rather easy for my biased palate to detect. I did some research and found some talk of people having different sensitivities to 3-MBT, which could help explain the split preference for the beers in this xBmt. Although, I guess it’s possible some people just like that lightstruck character.

Even if this xBmt had returned non-significant results, there’s no way it would have influenced my approach of fermenting in an enclosed dark environment. For those who may not have a fermentation chamber and ferment in clear vessels, I have no problems throwing my support behind the recommendation to keep your beer covered.

If you have any thoughts about this xBmt, please do not hesitate to share in the comments section below!

Support Brülosophy In Style!

All designs are available in various colors and sizes on Amazon!

Follow Brülosophy on:

FACEBOOK | TWITTER | INSTAGRAM

If you enjoy this stuff and feel compelled to support Brulosophy.com, please check out the Support page for details on how you can very easily do so. Thanks!

25 thoughts on “exBEERiment | Impact Exposure To Light During Fermentation Has On A German Pils”

Interesting xBmt!

Just a small fact. It’s not UV light that causes the skunking. Regular transparent glass filters more then 95% of the UV light, so if UV light was the cause, regular clear bottles would have been enough to protect the beer. It’s the visible light spectrum that causes the alteration (especially in the blue wavelength), meaning the theoretically artificial light could also cause skunking (fluorescent neon lights being the most dangerous, as the have more blue wavelength).

UV light filtering by glass depends on wavelength of light and color of glass. ‘Ordinary’ (non-UV-filtering) clear glass may filter the very short, higher energy wavelengths (the ones we need to protect our eyes against).

Edit: After rambling I realized I had a grudge against the clear glass bottles of Miller and Colona & lost perspective.

My reference point is clear glass and acrylic (glazing) used in picture framing, having researched UV-filtering of common clear materials. % filtering is simplified for the ease of selection. If you are familiar with frequency response, say for hearing tests, or audio equipment, you can see a graph that varies in level vs. frequency (and therefore wavelength, generally by principles of physics). % filtering depends on the amplitude or intensity of energy across the relevant spectrum. It’s really a graph than a simple %, but the latter is easier to compare between two levels of performance.

Light is not typically discussed in frequency but in wavelength, by convention.

UV, and the blue end of the visible light spectrum, cause fading of artwork and textiles because it is more energetic). Plain plate glass (non-specialty-UV-filtering) passes light longer than about 380 nm, and shorter than that. The picture framing and artwork preservation industry historically stated than conventional glass filters about 43% of light shorter than 380 nm. For comparison, non-UV-filtering acrylic (not practical for beer bottles, but for comparison) filters more UV, but with a non-linear graph, somewhere between 75 and 80%, but isn’t a specification to rely on. It’s discussed in lengthy papers on UV-filtering acrylic.

UV-filtering glass can only achieve more than 95% (it may now be as high as 97 or 98% in current marketing) of UV shorter than 380 nm without changing color (undesirable for photos & other artwork) by either a vapor-deposited coating (again, not practical for beer bottles), or by lamination of two layers of glass with a polymer layer in between). Automotive glass for front windshields is typically laminated, and one form of architectural security glass (the kind without visible ‘chicken-wire’ internally) are also typically laminated and block very close to 100% of the near-visible UV radiation. That is why your UV-darkening sunglasses don’t work well in a car. The other-than-front-windshield glass in vehicles is usually ‘safety glass’ that breaks into tiny pieces when broken. There used to be laminated picture framing/museum glass, but it was a PITA to cut.

UV-filtering conservation or museum acrylic glazing is about 1% better at low-energy UV filtering because it starts cutting the blue spectrum a little (below 400 nm, which is a visible shade of blue). That happens to cause fading of pigments, dyes, etc. as well, but colored glass for framing artwork is not desirable.

Beer bottles, with a couple peculiar exceptions like Corona and Miller, that use clear glass, are brown or green. THOSE bottles may achieve 95% of UV filtering as well as portions of the visible light spectrum.

So I went off on a tangent because Corona and Miller bottles still bother me. I don’t know what in beer produces skunk funk. In skunks, it’s a mercaptan molecule vaguely related to the thiosulfate molecule (both containing sulfur). So, do Corona and Miller not skunk because they lack sulfur, or do their consumers not care, nor does anyone making finer craft beer care either? Everyone reading this (zzzzzz) probably knows craft beer merits colored bottles.

The most dangerous shortest UV wavelengths are blocked by most glass, but possibly not enough to eliminate all safety precautions. Glass optical systems that require transmission of UV, and probably UV-sanitizing fluorescent lamps, typically require quartz.

The point about neon lighting is interesting. Neon, fluorescent, mercury vapor and related types similar are all classified as arc lamps, and may contain a mix of other noble gasses (neon, argon, xenon) that affect the voltage required to strike the arc. Most of them produce some significant UV also. That is what causes the white coatings in fluorescent lamps to produce specific visible wavelengths of light. Those are approaching obsolescence, unless your brewery is in an old building.

Some smaller CFL’s also contain some Neon gas because their shape and lower internal arc voltage require different conditions for the arc to be sustained.

Good experiment. I notice you live in Denver. I wonder if you have considering doing an experiment on the effect of altitude on brewing. I live in Nairobi Kenya, at about 6000 feet. I often wonder how the lower boil temperature effects hops utilization etc… Of course, it might be challenging to work out a way to test this at 2 different altitudes.

I really wonder this as well, we’ve discussed testing approaches but there are just too many uncontrollable variables for us to do it well.

I’d really be interested to know if the altitude effects mash temperatures results. Or does it just change the boiling point due to atmospheric pressure and has no effect on enzyme activity in the mash.

You might be interested in this paper: https://alchemyoverlord.wordpress.com/2016/03/06/an-analysis-of-sub-boiling-hop-utilization/

It discusses hop utilization at sub-boiling temperatures, but I expect it would be valid for boiling at higher elevation also.

A great exbeeriment. I’m surprised more didn’t pick it.

The glass in the sun experiment is a great one as I know in our Australian sun it takes 10 to 15 minutes for the “cat pee” aroma to come up.

Now we need a flourescent lighting test. This one was cool even if not practically relevant for me ( brew bucket.)

I’m interested in thoughts on light impacts at bottling. I bottle in my kitchen and, although I try to limit exposure, my clear carboy will sit uncovered during my process. I haven’t detected anything off, but would like to hear other opinions/experiences.

Something you could do is cover your clear carboy with a T-Shirt. You can easily lift a bit of it to see how much beer you still have left to transfer.

Me, too. My wild guess would be that the process of bottle conditioning takes care of the “skunky” flavor. Just a guess. Maybe like the beer gets a mini-reset to clear up any off flavors. I do though, bottle condition in my fermentation chamber at 68 degrees for two weeks then put them in a cabinet in my basement for 2 weeks to a year or longer, depending on style, at anywhere from 56 to 62 degrees.

Ha ha, “I began to experience a slight feeling of regret at this point”. I remember in my early twenties buying a bunch of Grolsch on clearance in dusty green bottles. No Idea how long they had been on the shelf (everything in that joint was usually dusty) , but the combination of time, room temp storage, and sunlight exposure must have really been working together, because that was the SKUNKIEST beer I have ever had before or since. Of course, being an impoverished 22 year old, I just thought that’s what that beer tasted like, and drank all of it.

I’ve always wondered if the sun hitting my boiling kettle has any impact on my beer. I’ve started to block any direct sun during the boil and whirlpool, just in case.

Hi,

Reading your articles I noted that you mill grains day before brewing. Why not on brewing day? It’s not much time consumption.

I do it because it’s simple to do the day before as I’m collecting water and saves me time the following morning when I’m brewing

Was this only in the sun for 5 days? Really seems a bit short, especially considering most will ferment much longer than that. Also, just as an FYI, glass filters out the majority of UV light coming into your house. This is why your left side doesn’t get sunburn in the car driving with the windows up early/late in the day.

Well, the result was significant, so in this data set the blind tasters were able to tell the difference between the beers, which would lead us to believe, in this instance, the variable had a perceivable impact.

Glass usually only filters UVB, the higher energy shorter wavelength light that is the cause of sunburns. UVA is often only slightly attenuated. Light in the blue-green spectrum with a wavelength of ~430-550 nm or so is what “skunks” or causes light strike to occur in hopped beer is only minimally attenuated through clear glass.

Lastly, the reaction takes seconds. Because most humans are very sensitive to the resultant compound 3MBT, or 3-methyl 2-butene 1-thiol, in the range of PPT (parts per trillion), it only takes a tiny amount to be detectable.

I have heard that reactions takes seconds, but in my experiments with bottles of Corona, just exposing it to sunlight for a minute or so and tasting immediately doesn’t produce as much skunkiness as if you expose it to sunlight for the same time but then allow to sit in a warm environment for say an hour, then chill and serve.

It takes seconds. You can taste a beer, is at an outdoor location such as a biergarten, and taste the beer change right before your eyes. However, due to adaptation, we often sense that the sulfur impound goes away while actually we just become used to it. Leave and come back – blamo, skunk city.

Quote from article “Interestingly, the differences in aroma seemed to fade as the beers sat out, leaving me to rely more on taste and had me wondering if the lightstruck character had dissipated”

Sounds like the opposite, one beer was already skunked, the other slowly joined it in the light and your taste buds adapted.

If skunking is so inevitable and quick we either need to accept it, drink in the dark or look at the brewing process to reduce available skunking compounds. Hop extract may have a place after all.

Had an uncovered fermenter with IPA sitting in a windowed, yet dark and shaded, basement for 12 hours post pitch. Covered it and moved it to a darker location. Which has me wondering, can beer be ‘saved’ from UV effects if caught early enough in the fermentation process?

How did you work out p values?? Twenty tasters making a binary choice…..so expected value would be 10 in each category. I would use chi squared to compare observed vs expected number of tasters picking out light struck beer……and would be very surprised if the 11/20 would be significantly different from 10/20 (obs – exp).

Growing up in North Germany I grew up with Beck’s (in green bottles…). I always wondered why the first whiff when you opended the bottle smelled like cannabis. I love it, wouldn’t drink it without the smell… Nevertheless, I am now replacing the 100Watt lightbulb that acts as a heat source in my fermentation chamber with a ceramic heat source.

NOW I read the rest of the posts! Interesting. I don’t even know how I got here.

I remembered how I fell into this website.

I am carpet cleaning (done, and about to open a beer) after having two sick dogs for a week and a half.

I had purchased some UV flashlights & checking what dog ‘output’ still fluoresced, and rechecking afterward.

I found some spots at either corner of a couch that glowed. I could blame an earlier dog ‘event’, but those are where two friends both knocked beers over. One was a stout, and the other was Modelo or PBR (diverse beer friends).

I cannot reduce the brightness of the carpet there after a few cleanings. Something there doesn’t act the same. I assumed dog whiz and beer differ in multiple ways, but the most obvious is yeast in the beer.

I don’t know what wavelength my UV flashlight outputs, but I was disappointed a finger cut dripping blood didn’t glow. Maybe because I’m still alive, or on black & white TV it only worked for chocolate syrup fake blood.

Google dumped me here looking for UV detection of beer yeast but I probably spelled something wrong.

My first apartment in another US sate – I too wondered why all the European lagers & Pilsners in the grocery store were so bad & why people liked the skunkiness. I was then annoyed it was handled so poorly (early 80’s).