Author: Matt Del Fiacco

Presumably due to the availability of cheap 6 gallon fermentation buckets, 5 gallons/19 liters has become the standard batch size in modern homebrewing, which also happens to fit conveniently in corny kegs. Of the various wort production methods that exist, there seems to be ubiquitous agreement that boiling the full volume produces a higher quality beer, hence the gear upgrade aspirations of many a new homebrewer. While relatively common in extract brewing, it seems partial boils are rarely practiced by those relying on all grain methods, perhaps due in part to the bad rap it’s received over the years.

Often criticized as a method that produces a darker beer with a higher chance of contamination due to the addition of dilution water, there are a number of conveniences to partial boils as well. For example, a full 5 gallon batch of beer can be boiled in a smaller and less expensive kettle, cold dilution water can eliminate the need for a wort chiller, and hitting a precise OG is as easy as making small adjustments to the dilution volume.

For the purposes of this article, the term partial boil refers to the method of producing a high OG wort that’s approximately half the intended batch volume and diluting it with water to the target batch volume after the boil to reach the proper volume and OG. There are quite a few factors to consider when using this method such as the water to grist ratio, hop utilization in the boil, and pH of the wort, all of which are believed to effect beer character. Curious of the impact of a partial boil, and admittedly interested in methods for simplifying my brew day, I was excited to put this one to the test!

| PURPOSE |

To evaluate the differences between a beer made using the partial boil method then diluted with water to the proper volume and one where the full volume of wort was boiled.

| METHODS |

After several high-gravity ale brews, I wanted to put a flavorful lager on tap and decided on my standard Munich Dunkel recipe for this xbmt.

It’s A Slam Dunkel

Recipe Details

| Batch Size | Boil Time | IBU | SRM | Est. OG | Est. FG | ABV |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 4.5 gal | 60 min | 21.7 IBUs | 10.7 SRM | 1.051 | 1.018 | 4.3 % |

| Actuals | 1.051 | 1.014 | 4.9 % | |||

Fermentables

| Name | Amount | % |

|---|---|---|

| Munich I (Weyermann) | 4.312 lbs | 50.36 |

| Munich II (Weyermann) | 3.875 lbs | 45.26 |

| Caramunich I (Weyermann) | 6 oz | 4.38 |

Hops

| Name | Amount | Time | Use | Form | Alpha % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Magnum | 9 g | 60 min | Boil | Pellet | 11.6 |

| Tettnang (Tettnang Tettnager) | 12 g | 30 min | Boil | Pellet | 4 |

Yeast

| Name | Lab | Attenuation | Temperature |

|---|---|---|---|

| Urkel (L28) | Imperial Yeast | 73% | 52°F - 58°F |

Notes

| Water Profile: Ca 21 | Mg 4 | Na 8 | SO4 31 | Cl 30 |

Download

| Download this recipe's BeerXML file |

I made a starter of Imperial Yeast L28 Urkel a few days ahead of time, my first time using this strain.

To start my brew day off, I added the full volume of water (6.5 gallons/25 liters) to both kettles, adjusted each to the same profile, then removed precisely half of the water from the partial boil kettle.

I then turned the heating elements on.

While the water was warming up, I weighed out and milled my grains.

As expected, the smaller volume of water reached strike temperature before the full volume batch, so I mashed in on it first. Once both were going, the difference in mash thickness was very apparent.

I set the controllers on each batch to maintain the intended first mash step temperature of 146°F/63°C.

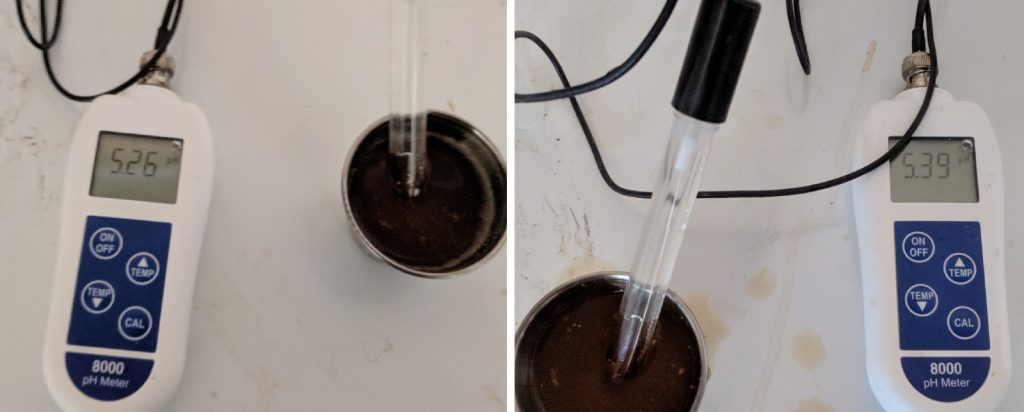

At 15 minutes into each mash, I pulled samples of wort to measure the pH and noticed a predictable difference.

At 30 minutes into each mash, I set the temperature controllers to the second mash step and checked 10 minutes later they hit my target of 160°F/71°C.

Once each mash was finished, I removed the grain baskets and let them drain while the wort began heating. Again, due to the smaller volume, the partial boil wort reached a boil before the full boil batch.

The worts were boiled for 60 minutes with hops at the appropriate times. Once complete, I quickly chilled each batch by running it through my counterflow chiller directly into fermentation kegs.

It was at this point I noticed what seemed to be noticeably more break material in the full boil kettle.

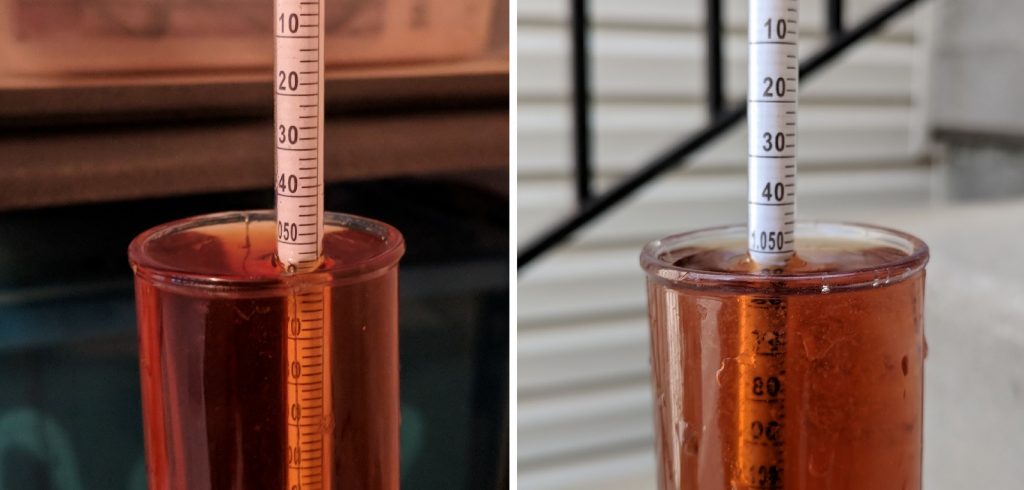

Once chilled, I set the fermentors in my chamber then proceeded with boiling the dilution water I’d previously saved from the partial boil batch for about 15 minutes to sterilize. After letting it cool for a bit, I added it to the dilution batch then took hydrometer measurements of both worts showing a 0.001 SG difference. Not too bad for a first attempt.

The worts were left in my chamber until they stabilized at my desired pitching temp, at which point I split the yeast starter equally between them. I noticed activity in each 12 hours later and let them ferment for 5 days before slowly raising the temperature to 70°F/21°C over the course of 3 days.

After a 3 day diacetyl rest at this warmer temperature, I transferred the beers to serving vessels, attached spunding valves, and eased the temperature down to 36°F/2°C where they lagered for 2 weeks. Hydrometer measurements at this point showed the FG of the partial boil batch was 0.002 SG higher than the full boil beer.

The beers were placed in my keezer and briefly burst carbonated before I reduced the gas to serving pressure. After another week of cold conditioning, the beers were ready to serve.

| RESULTS |

A total of 23 people of varying levels of experience participated in this xBmt. Each participant was served 2 samples of the partial boil beer and 1 sample of the full boil beer in different colored opaque cups then asked to identify the unique sample. While 12 tasters (p<0.05) would have had to identify the unique sample in order to reach statistical significance, only 9 (p=0.35) made the correct selection, indicating participants in this xBmt were unable to reliably distinguish a partial boil Munich Dunkel from one made using the full boil method.

My Impressions: Out of the 6 triangle tests I attempted, I correctly picked the odd-beer-out only twice, which is exactly inline with random chance. Despite my best efforts, I just could not tell these beers apart. I expected the full boil beer to be a touch more bitter due to decreased hop utilization from the higher gravity of the partial boil wort, but at the end of it all, everything about these beers was identical to my senses.

| DISCUSSION |

Of all of the recommendations given to new brewers looking to make their beer better, moving from partial to full boils is pretty high on the list. Like I imagine is true for most, my initial brewing setup included a small 4 gallon kettle, limiting me to partial boils if I wanted to make 5 gallons of beer. Like I also imagine is true for most, I was convinced by what I’d heard from more experienced brewers that getting a larger kettle and performing full boils would drastically improve the quality of my beer. When I eventually made the transition, I did think my beer was better, and I believed this was due in part to my departure from partial boils. Admittedly, the results from this xBmt showing neither participants nor I could reliably distinguish beers made using either method left me dumbfounded. Where did these supposed truths originate? How did it become commonly accepted that a partial boil produces worse beer than a full boil?

I don’t doubt there are certain objectively measurable differences between beers produced using either partial or full boils, but these results demonstrate both methods can create beers of equal quality on a perceptual level. Of course, an obvious caveat to these findings is that both beers were produced using an all grain method, leaving open the question of whether the results hold true when brewing with extract, which I look forward to exploring in the future.

If you have any thoughts about this xBmt, please share them in the comments section below!

Support Brülosophy In Style!

All designs are available in various colors and sizes on Amazon!

Follow Brülosophy on:

FACEBOOK | TWITTER | INSTAGRAM

If you enjoy this stuff and feel compelled to support Brulosophy.com, please check out our Support page for details on how you can very easily do so. Thanks!

50 thoughts on “exBEERiment | Impact A Partial Boil Has On An All-Grain Munich Dunkel”

I commonly add boiled water after boil if i miss my target. when you add a lot of hops or do longer boils you end up with less wort. Although this dilution is nowhere close to what you did. But if you were to do a fermentation with high vs. low gravity beer, and then post fermentation dilute high gravity to match low gravity beer, you probably will get noticeable difference.

This sounds like great news for brewers that don’t have a wort chiller and/or a large boiling vessel. Both of which I didn’t start with. Nice exbeeriment 😀

Hey thanks! I think that’s definitely one of the potential advantages. If you want to be brewing larger batches, but don’t have the equipment, this is an option. And it’s a great chilling option as well until you can justify sinking the cash into a chiller (or don’t, if this works!).

Like any brewing set up, it would require some dialing in and knowing your system, but it’s an option. I enjoyed it, and might be using it in the future when it gets a bit too cold in the garage!

Wow Matt! Your post really made my day! I am now really considering getting into All Grain. Not really sure if a 20 Liters (5.5 Gal) Kettle would do the trick.

Thanks for all the great info you share!

Cheers!

I’ve successfully done all grain batches in a 5 gallon pot! Brewhouse efficiency hits right around the 65% mark (I don’t know if this is due to a thicker mash or some other variable), but you can make tasty beer on a stovetop!

I recall the instruction sheets from my first couple brews from ~1991. Generally, they had you start with 3 gallons of water… add extracts, boil, add hops, boil more, add more hops, boil a little more. Top off with *cool tap water* to 5 gallons, pitch dry yeast when below 80*F. Cover and wait. The more I read, the more it seemed that unboiled, unfiltered tap water might not be a good idea. To their credit, they were otherwise pretty good about preaching sanitizing habits.The resulting beer was good enough that I kept on brewing, but I wouldn’t dream of letting unboiled water *near* my fermenter nowadays.

Btw, Matt, I like your writing style.

Totally agreed. I think partial boil could address quite a few issues for new brewers, but definitely boil that water!

And thanks! The articles are edited collaboratively so we maintain the voice of the site, but you get splashes of our personality and approach as we go.

According to J. Palmer, danger zone for contamination is below 60C (140F). Hence, if boiled off wort + cold water combo is above this, than cold tap water should be ok to use. Let’s do the math:

m1*t1 + m2*t2 = tf * M

m1 = 2.5 gal (boiled off wort vol)

t1 = 100C (wort temp)

m2 = 2.5 gal (cold water addition)

t2 = unknown (cold water temp)

tf = 60C (desired final temperature)

M = 5 gal (total volume, m1 + m2)

which yields t2 = 20C . So, if your tap water is 20C or above, there is no danger of contamination. If the tap water is colder, then you might want to increase the boiled-off wort volume and decrease the cold water addition. For example, if cold tap water temp is 10C, then we can solve for the necessary boiled off wort volume:

m1 = unknown

t1 = 100C

m2 = M – m1 galons

t2 = 10C

tf = 60C

M = 5 galons

which yields m1 = M*(tf-t2)/(t1-t2) = 2.78 gallons. Hence if we have this much or more of boiled off wort volume, then we will end up at 60C or above with no risk of contamination. These calculations and formulas are also true for Fahrenight scale.

Nice write up! I have brewed many partial mash beers with top up water in the winter with excellent results. I’ll have to try this with all grain batches to simplify my brew day.

Thanks!

“the partial boil batch was 0.002 SG lower than the full boil beer.”

“Left: partial boil 1.016 | Right: full boil 1.014”

Don’t you mean .002 higher?

I do, thanks! I’ll make that edit.

Sorry, didn’t mean to be “that” guy. 🙂 Interesting experiment and a nice write up to be sure!

Dude not at all! I appreciate the correction.

A shorter boil might have a greater impact on Pilsner Malt. The DMS problems are driven off with a longer and strong boil.

Could be! Thankfully no pils in this recipe, and we didn’t adjust boil length at all. If there were pilsner malt, it would have been boiled for 90 minutes.

Pilsner malt needing a longer and harder boil has been myth busted by Brülosophy, among others.

Like you, I expected this to show significance. Since it didn’t, it made me realize that I know of breweries (both macro and local craft) that brew a stronger strength beer that is then diluted with water. I believe the craft brewery dilutes pre-fermentation as well. Maybe it’s extract?

It could be! This also may have been significant if dilution was done post-fermentation. For now, I think it suggests that this is a viable option that people should try for themselves if they don’t want to sink the space or money into larger equipment. Or if they just want to shorten the brew day a bit.

With double the water volume in the full boil mash, the sugars would be much more dilute, yielding roughly half the lautering loss. I’m at a loss as to how the efficiencies could be so similar with these two batches. Do you have any thoughts about this? Or have I missed something?

Hey Glenn!

I think I have an answer for you, but I want to make sure I’m answering the question you’re asking. If you’re saying:

“Why was the efficiency so similar, when the thicker mash should result in lower efficiency”, then the answer would be “I frequently gently stirred the mash, and have the luxury of recirculation”. Plus the more intense boil-off, means slightly lower total volume, which means same amount of sugar in a smaller volume.

If I’m missing the mark, can you rephrase the question a bit? Cheers dude!

Yes – your understanding of my question is correct. Fascinating, as Mr. Spock would say. I find the efficiency results even more surprising than the similarity in beer character.

Same, a few people have brought that up. I’m still scratching my head a bit. Planning to repeat this soon!

“Of all of the recommendations given to new brewers looking to make their beer better, moving from partial to full boils is pretty high on the list.”

Wouldn’t it be more “moving from partial MASH to full MASH?” I don’t think that novice brewers commonly do a full mash but with only partial boil volume.

I think that is definitely a variable as well, but we wanted to isolate a single variable as best we could without trying to compare to sets of practices that result in a few different changes. We’ve done that before though, and it might be a really cool xbmt. Thanks for the feedback!

Nice article Matt! I’m curious about your recirculating arm in the kettle? I’ve been seeing these pop up in photos on social media. I’m about to start recirculating my mash and wondered what are the advantages of this device? Are you just putting directly into the mash water or drizzling? Does this create channeling I’ve read about? Sorry about all the questions but I haven’t found much info from users.

Hey dude, no worries! You can always reach out to me individually with questions as well.

The recirculation arm is called Loc-Line. The advantage is that is both rigid and flexible, which allows for two things:

1. Angling of the arm to create a “whirlpool” effect in the mash, which helps reduce channeling and creates more motion in the mash.

2. Lets you set the outlet directly below the top of the mash, which in theory helps prevent one channel for hot side aeration, but for sure means less splashing than just drizzling over the mash.

It just works for my system, there are a lot of viable options! Love Loc-Line though (just don’t use it for boil).

Thanks for the insight. I might give this a try as it is less expensive as most SS options I’ve found. Cheers!

This is brilliant. I generally do 20l mash in + 6 l “sparge” on my BIAB set up which gives me ~21 l in kettle (average of 75% efficiency). After 1 hour boil I have 17l in kettle and I top off with 5l 10°c water to drop the temp quickly from 100 to 75c. From there it is a plastic cube container of ice to chill down to 30c because I hate wasting water and can clean and reuse the ice/water. I often wondered if the flavor/quality would suffer. Glad to know it is not discernable

Well if you are adding cold water from a sanitized vessel and the wort is already at boiling , wouldn’t boiling the additional water be redundant?

Water, depending on the source, can harbor a lot of bacteria and such. So as you add water and the total volume cools, the water that has yet to be added is introduced to an increasingly optimal environment. Might not be a problem, but certainly safer to pre-boil.

However. … in a LOT of winemaking instructions you will find the advice to simply add cold TAP WATER to your must. Jack Keller talks a lot about this. And not many know more about home vintning than him!

I’ve never had a problem with my wine made that way. Then again wine is s little higher in alcohol and the OG is higher so your fermentation is more vigorous than for beer so perhaps competitive inhibition is at play?

However wine is kept stored for longer and winemakers panic even more than brewers about wild yeast getting a foothold. I think good quality tapwater is unlikely to spoil your beer as long as you remove the chlorine/chloramine. I doubt you’ll find any evil anti-beer yeast or bacteria surviving municipal water treatment.

Glad to see the result as I nearly always top up my wort after chilling, though usually only with 0.5-1 gallon of water. There are lots of advantages to doing a concentrated boil:

* Faster chill

* Can accelerate chill by diluting with ice instead if water

* Brew with smaller boiler/stockpot

* Quicker to bring wort to the boil

* Use less fuel

* Less risk of boilover, less mess if you brew in a kitchen

* Don’t need to sweat over targets, boiloff rate, etc. – just correct gravity at end

I’ve never bothered sanitising my tap water. I just don’t believe the cell count of lactobacillus in tap water is significant – how would beer-spoilage organisms get into mains water?

I haven’t tried boiling a 2x concentrated wort but it’s a fantastic idea and worth exploring further.

I definitely wouldn’t dilute after fermentation – you might end up with watered down barley wine rather than normal beer.

Maybe not in the water supply per se, but with three kids in my house I would highly doubt that my faucets are bacteria-free. Little germ factories.

Hi Matt. What were your post boil volumes for the two? – before adding water to the partial. Am I correct that you added the whole 12.5 litres to the partial boil after boil? And were the volumes after dilution the same? Thanks!

Hey!

Post boil, they were about 4.7 gallons and 1.1 gallons, before adding water back. And you are correct, added those 3.3 gallons (12.5 liters, I gotta learn metric) after the boil. The final volumes ended up being 4.7 gallons and 4.4 gallons.

Wow, that’s a massive difference – I look at those two figures and think that it is a significant process variation (like fresh orange juice and concentrate) which accentuates my surprise at the tasting results. Again, wow! Cool experiment. I’m down here in fully metric New Zealand and it makes life so easy, yes everything divides by factors of 10, but most Americans don’t know all the metric units are related to each other in easy to work out ratios. For example a Newton (measere of force) is the force required to accelerate 1kg by 1m/second and a Watt (measure of power) is the work needed every second to keep an object at 1m/s constant velocity against an opposing force of 1 Newton. Sound complicated? Yes, the concepts are, but the maths itself is not! Woops, sorry for wandering off topic…

Forgive me if this should be more obvious, but this was done without sparging the grain at all, right? Assuming this is the case, it helps square it more in my mind how the gravity (and efficiency) was essentially the same between the two.

So potentially, there was still some small amount sugar left in those grains, that if sparged would have improved your efficiency, which isn’t really an option with the smaller volume boil. I guess what I’m trying to get around to is that if you are at all concerned about brewhouse efficiency (which I know not everyone is), then you’d expect the drop in efficiency to be roughly the same for partial boil, no-sparge and no-sparge full boil, as compared to traditional sparged full boil, yes?

Great article. Here in Ohio we have had a cold winter and I like to brew in the garage for many reasons. With a smaller volume boil I make 2 1/2 – 3 gallon batches and cool my wort in a laundry sink but now I am going to make a 5 gallon batch using your method. You guys have changed the way I brew with your exbeeriments and sharing of knowledge. Thanks and keep up the good work. (and wort!)

Hi there,

nice article!

I have added unboiled water for 70 brews now directly to the fermenter after my partial boil, so not used the water for cooling, but only to add up in the fermentor! I have never had any issues (2 contaminated brews I guess from other issues)…..but living in Denmark where we have the most restitive rules for protection of groundwater with no treatment nor addition of chemistry to the drinking water, it is completly possible to make use of tap water. But you need to know it hold low micoboactic activity and hold not clorinated chemicals, else I would not use it!

Secondly, if you hold clean water and you add it from the tap you alo ensure a very good way of adding oxygen to the wort prior to the fermentation.

3rd´ly I am starting to thinking, why not freeze 3 liters boiled water and add it the just boiled wort to lower temp. and hence stop the isomazation, e.g. 3 liter ice at -10`C + transition energy, would lower a allmost boiling wort till 75`C (sorry for using the metic system, but you guys need to learn it….), hence, a very easy way of lwoering the temp parts the isomazation point!

I cool over night by warping alu-foil + plastic, and try to get temp. down but putting the put in cool water….but I am really starting to consider using ice to cool too:

http://www.haandbrygforum.dk/download/file.php?id=6694&t=1

Klaus

Brewing ‘High Gravity’ worts to be liquored back are common in commercial brewing. Here’s some interesting further reading with scientific data on the end results: https://www.newfoodmagazine.com/article/1550/high-gravity-brewing-the-pros-and-cons/

Thanks for the resource! Can’t wait to look into it more.

GREAT NEWS ! Now I can brew 2 x 5 gal batchs in my 9 gal kettle !!!!!!!!

Good experiment, thanks for doing this. Since someone gave me an extract kit, I plan to do this soon with extract and ice. (I’ve brewed all grain for about 12 years, so the short brew day will be welcome).

I wonder if conventional wisdom is about equipment and various risks. I have made beer for example, by diluting with unboiled water without issue, clearly that’s a higher risk, which you’ve accounted for by taking extra precautions. Also perhaps somebody with a poorly designed grain holding system might experience more burnt grain near the elements/bottom of the pot.

The point is, maybe sometimes risks can be avoided with common sense/careful methods, while common wisdom is trying to account for the errors (inexperienced) brewers are likely to make.

I see a major anomaly here which should lead to disregarding the results IMO — the full-volume mash batch (6:1 grist-water ratio, w/w) had an actual mash efficiency of 76.5% while the half-volume mash batch (3:1 grist-water ratio, w/w) had an actual mash efficiency of 86%. Read that again and think about that. Therefore, these results seem unlikely to be repeatable in terms of the beers’ specs.

To put it another way, the 3:1 ratio batch is like the first runnings of a partigyle beer. You would not expect it to be as efficient as a batch that used the whole volume of mash water (6:1 ratio). It’s a simple matter of lauter efficiency.

Something strange happened. I don’t know if the mill gap slipped, or there was some sort of equipment error or human error, or something else.

I wanted to verify my numbers with the author, which I have done, before I posted this.

The concept is an exciting one, but perhaps the xbmt deserves to be re-run in light of this anomaly.

If I’m reading this correctly, and yes, I did read it again and think about it, what you’re basically saying is that it doesn’t make sense to you that the partial boil mash, which used half the amount of water as the full boil mash, had the extract efficiency it did. When I plugged the numbers into a calculator, everything seemed to check out, with the actual mash efficiency being 78% for the full boil batch and 76% for the partial boil batch. Perhaps his use of recirculation throughout the mash rest had an impact? In the end, both worts had about the same amount of sugar, which isn’t terribly surprising. Are you suggesting a lower water to grist ratio ought not extract as much sugar, like the water reaches some saturation point or something? Regardless, the fact this doesn’t align with expectations can be tough to swallow, I get that, and we absolutely plan to repeat the xBmt just as we hope others do as well!

As for the potential explanations you provide regarding why this happened, your “or something else” comment seems to call Matt’s integrity into question. Again, it makes sense to seek explanations, but I just want to get it out there that we’re not nearly invested enough in producing particular outcomes to be deceitful in our reporting of process and results. Matt gave a detailed account of how he brewed these beers in the article, he didn’t do anything else, and I trust that.

I believe you made an error in your calculation. Specifically, you didn’t account for the fact that you lost wort to kettle loss: 4.2% of the 1.051 SG post-boil wort from the full volume mash, but a massive 15.4% of the 1.207 post-boil wort from the partial volume mash (0.2 gallons in each case).

Therefore, because you have lost a major part of an absurdly high SG post-boil wort (lost 0.2 gal of 1.3 post-boil gal), your mash efficiency on the partial-mash batch has to be even higher than the 76% you back-calculated.

Actually, the efficiency on the partial volume-mashed batch was an improbable 86%, and the efficiency on the full volume-mashed batch was an ordinary 76.5%. Here is a link to my spreadsheet, for which I got the raw numbers from Matt and then I had him verify my conclusions before I commented here: http://bit.ly/2rqfnIV.

I mean this as a friend: I know you’d like to write this off as me being butthurt because some result didn’t fit with my world view on brewing. But the reality of it is that the experiment had a major anomaly that we cannot explain an which renders the experiment defective.

The correlation between the wort collected-to-grist-ratio and lauter efficiency is not some sort of old wives tale that can be “busted” like warm fermenting a Sacch lager yeast. I’m not kidding that if you’ve unlocked some secret to brewing double strength with greater efficiency, then you’ll be selling your discovery to AB Inbev or Coors for millions.

Further, just because two beers went through a blind triangle doesn’t validate the experiment, any more than if I did a blind triangle on Bud Light vs SNPA and got p>0.05, but it turned out I accidentally served Full Sale Pale Ale vs SNPA — that anomaly invalidates the experiment.

You guys aren’t infallible, and sometimes I feel like you guys don’t have an open mind when others suggest you may have messed up. The choice of method and style is a design choice. BUT GETTING 10% HIGHER EFFICIENCY BY USING 50% LESS WATER IS EITHER A MAGIC TRICK OR A MASSIVE EXPERIMENTAL ERROR.

1. As a friend, I don’t care how you feel about something as trivial as a homebrew experiment, so we good there.

2. Personally, I think your voice might be a little louder if rather than complaining about a result you didn’t like, you did something to replicate.

3. We aren’t infallible, indeed, and one person’s complaint doesn’t automatically invalidate either. Replication!

4. The only part of your complaining I take somewhat personally is your covert questioning of Matt’s integrity. You’ve positioned these results, on a variable you’ve never actually tested, as either an anomaly or Matt making stuff up. It could also be that it’s not magic or a massive experimental error, it could be, despite your beliefs, the actual findings.

Rather than argue with you about the findings, which I trust could go on forever, we’ll do the more effective thing and retest it. I suggest you do the same, it’s way more fun than bloviating about opinions. Cheers!

I would rather use a bit more barley and hops to account for decreasing efficiency in partial boil (if any) than purchase a bigger and expensive kettle and other things to do all grain.