Author: Marshall Schott

Base malts generally make up the largest proportion of the grist in beer recipes, supplying the diastatic power necessary to enzymatically convert starch to fermentable sugar. The most recognizable base malts are standard Pale and Pilsner malts, both produced from 2-row barley that’s kilned to a relatively low degree. However, despite their heavy presence in the majority of today’s beers, they aren’t the only options.

Often misconstrued as specialty malts, both Vienna and Munich malts are also classified as base malts that can be used in the same manner as any other base malt, even as 100% of the grain bill. While occasionally compared to each other and even viewed as viable substitutes, Vienna and Munich malts are different in that they are kilned to different degrees, the former typically falling within a range of 3-5 °L while the latter is slightly darker at 5-10 °L. Used in paler styles such as Vienna Lager, Festbier, and Maibock, Vienna malt is generally described as adding a subtle malt sweetness and toasty character to beer. In comparison, Munich malt is known for imparting rich malty and bread crust flavors expected in styles like Märzen.

I’ve used both Vienna and Munich malts in hundreds of batches over the years, often featuring it in small amount as an accent, though occasionally using it in higher doses to add more character than I expect from other base malts. Having never evaluated beers made with either side-by-side and curious to try Weyermann’s Barke line, I snagged a sack of each on a recent grain order and designed an xBmt to see how they compare!

| PURPOSE |

To evaluate the differences between beers made with a grist consisting entirely of either Vienna malt of Munich I malt.

| METHODS |

Single malt recipes are surprisingly easy to design. Since I wanted to make sure any differences caused by either malt came through, I went with a simple hop schedule and clean lager yeast.

WienerMünchen

Recipe Details

| Batch Size | Boil Time | IBU | SRM | Est. OG | Est. FG | ABV |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5.5 gal | 30 min | 26.1 IBUs | 8.4 SRM | 1.050 | 1.012 | 4.9 % |

| Actuals | 1.05 | 1.017 | 4.3 % | |||

Fermentables

| Name | Amount | % |

|---|---|---|

| Vienna OR Munich I (Weyermann) | 10.5 lbs | 100 |

Hops

| Name | Amount | Time | Use | Form | Alpha % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Magnum | 18 g | 30 min | First Wort | Pellet | 12.2 |

| Hallertauer Mittelfrueh | 30 g | 15 min | Boil | Pellet | 2.4 |

Yeast

| Name | Lab | Attenuation | Temperature |

|---|---|---|---|

| Global (L13) | Imperial Yeast | 75% | 46°F - 56°F |

Notes

| Water Profile: Ca 75 | Mg 1 | Na 10 | SO4 86 | Cl 75 |

Download

| Download this recipe's BeerXML file |

I started off by throwing together a single starter of Imperial Yeast L13 Global a couple days ahead of time.

The afternoon before my brew day, I weighed out and milled the grain while filling a single mash tun with the entire volume of brewing liquor required for both batches.

I placed my heat stick in the water and set a timer to turn on about 2 hours before I planned to start brewing the next day.

I woke up to water that was quite a bit warmer than my target strike temperature, which I planned since it was expected to lose some heat racking half to a second cool mash tun. Once the transfer was complete, I placed a lid on the first mash tun then stirred the second until the water dropped to strike temperature before adding the Vienna malt grist. Twenty minutes later, after ensuring the brewing liquor was at strike temperature, I mashed in the Munich malt batch.

Judging by the similar mash temperatures, both of which were right on target, I’d say my calculator worked.

I stole a small sample of wort from each batch 15 minutes after mashing in to measure the mash pH and found a predictable difference.

Following each 60 minute mash rest, I collected the full volume of sweet wort.

The worts were boiled for 30 minutes with the same amounts of the same variety of hops added at the same times.

At the end of each boil, I quickly chilled the wort to slightly warmer than my groundwater temperature.

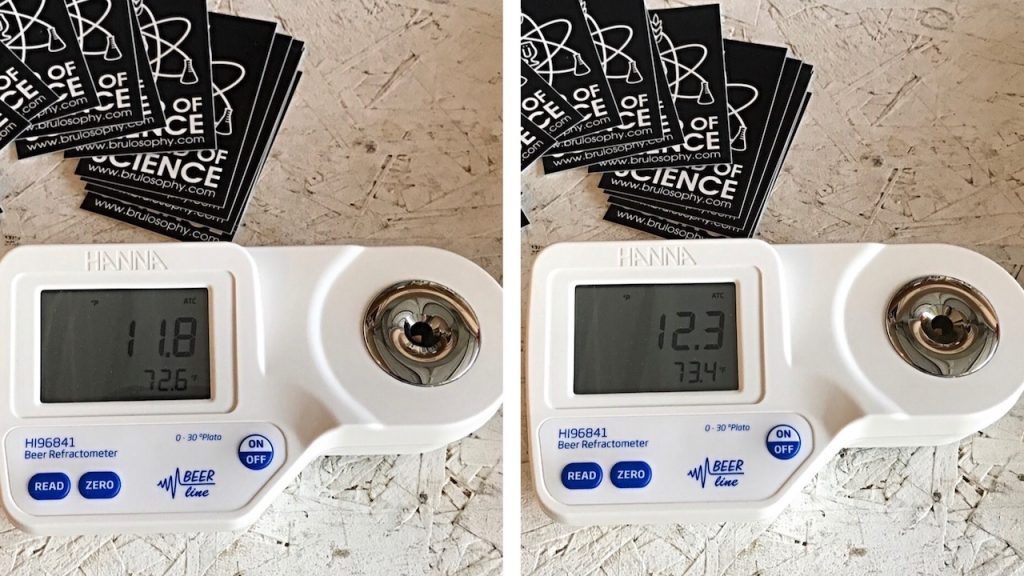

Refractometer readings of the chilled worts showed a small difference of 0.5 °P, or about 0.002 SG points, with the Munich malt wort clocking in a little higher than its Vienna malt counterpart.

I proceeded to rack equal amounts of wort from either batch to sanitized fermentation vessels.

The fermenters were placed in a chamber where they were allowed to finish chilling to my desired fermentation temperature of 60°F/16°C. I returned 4 hours later to perfectly chilled worts and pitched equal amounts of the yeast starter into each. Fermentation activity was present in both batches a few hours later and I let them rip along for 6 days before increasing the temperature to 70°F/21°C. After a 4 day diacetyl rest with all airlock activity absent, I took hydrometer measurements and discovered the Vienna malt beer attenuated a bit more than the Munich malt batch.

The beers were cold crashed overnight and fined with gelatin before being kegged.

I placed the filled kegs in my keezer where they were burst carbonated at 50 psi for 14 hours, after which I reduced the gas to serving pressure and let them condition another week before collecting data. While the difference in color was stark, both beers were equally clear and carbonated.

| RESULTS |

A total of 21 people of varying levels of experience participated in this xBmt. Each participant was served 2 samples of the Vienna malt beer and 1 sample of the Munich malt beer in different colored opaque cups then asked to identify the sample that was unique. While 12 tasters (p<0.05) would have had to accurately identify the unique sample in order to reach statistical significance, 13 (p=0.007) were capable of doing so, indicating participants in this xBmt were able to reliably distinguish a beer made with 100% Vienna malt from one made with 100% Munich I malt.

The 13 participants who made the accurate selection on the triangle test were instructed to complete a brief preference survey comparing only the 2 beers that were different. A total of 6 reported preferring the Vienna malt beer, 5 liked the Munich malt beer more, and 2 reported having no preference despite noticing a difference.

My Impressions: As someone who has used Vienna and Munich malts in various amounts in many beers, I’d developed a belief they produced starkly difference flavors. To my utter surprise, both the Vienna and Munich malt beers were way more similar than I expected, to the point I had to focus really hard on the 7 triangle tests I attempted. While I was able to identify the unique sample in 5 of these trials, I could definitely understand how some might struggle to tell them apart, especially when unaware of the variable. I perceived a stronger malt character in the Munich malt beer that was very inline with what I expect from a Märzen, some toasted bread character and a slight hint of honey was present as well. The Vienna malt beer had a similar malt sweetness, though it was lighter on the palate and had a very curious raw bread dough thing going on.

| DISCUSSION |

Continental base malts like Vienna and Munich not only make up the majority of grists in certain classic European lager and ale recipes, but have become a popular option for brewers of more modern styles looking to impart unique characteristics to their beer. Given their differences in kilning that leads to obvious differences in beer color, it’s not terribly surprising tasters in this xBmt were able to reliably distinguish a beer made with Vienna malt as 100% of the grist from one made with the same amount of Munich malt.

What I do find kind of surprising is the unexpected number of participants who weren’t able to tell these beers apart, 8 in total, which prior to my own triangle test attempts I admittedly thought might be an indication of their tasting abilities. It was only after choosing the wrong sample in 2 out of my 7 trials that I realized these malts weren’t as drastically different as I’d previously presumed. While the differences were certainly noticeable, the similarities between the beers were more obvious when unaware of the color differences, both shared pleasant crackery and toasty notes. However, where it seems they diverged, based on participant feedback as well as my own impressions, is that the Vienna malt beer was lighter on the palate with a raw bread dough character while the Munich malt beer was slightly richer with notes of honey and toasted bread crust. Different, indeed, but not nearly as obvious as I expected.

I generally keep bulk Vienna and Munich malts on hand, typically using them in conjunction with other base malts to add a toasty character to my beers. Having used both as the feature malt numerous times in the past, I’d developed a pretty good idea of what to expect from them, and while this xBmt was validating, I was pleasantly surprised with how much I enjoyed the Munich malt beer. It was so good, in fact, that I plan to use the same simple grist for Oktoberfestbier I make in the future.

If you have any thoughts about this xBmt, please do not hesitate to share in the comments section below!

Brülosophy Merch Available Now!

Follow Brülosophy on:

FACEBOOK | TWITTER | INSTAGRAM

If you enjoy this stuff and feel compelled to support Brulosophy.com, please check out the Support page for details on how you can very easily do so. Thanks!

50 thoughts on “exBEERiment | Grain Comparison: Vienna Malt vs. Munich Malt In An International Pale Lager”

Hey Marshall, Thanks for doing this.

Btw, you kind of trailed off just prior to the discussion heading.

he fell asleep from drinking too much lager! also, the hops description confuses me. they weren’t FWHs were they? one FWH at 15 and one at 30 min?

Were the tasters blindfolded? Without even tasting it’s clear which sample is different just based on color, at least in the clear glassware. I could understand if the tasters couldn’t see the samples that they might not be able to identify it just based on taste.

The samples are served in different colored opaque cups, so yes, participants are unaware of any color differences.

Can’t you see from the top of the cup?

Foam was a little darker on Munich, but in a red cup, it didn’t matter. We also specifically tell people prior to every survey, “This is not a test of appearance, please only focus on aroma, flavor, and mouthfeel.”

Hi there Marshall, great job. One detail: You forgot to say which batch was which on the pH reading! Cheers!

the munich was lower, duh. 🙂

Whoops. Fixed!

‘it had a very curious’,,, what?? I’m dying to know.

Fixed– “…raw bread dough character.”

Marshall, did the Munich beer have a noticeable difference in mouthfeel given the large difference in FG’s between the two? In addition, might the FG difference be attributed to the low pH of the Munich mash (4.88)? This would translate into a pH of ~4.3-4.4 at mash temperatures. Might this have resulted in a less fermentable wort? Thanks

The mouthfeel between the beers was definitely not noticeably different to me, and given my experience comparing beers of drastically different FG, I’m doubtful that’s what gave it away. It’s certainly possible the low mash pH impacted FG.

Marshall, what was the degrees L on the two malts? Thanks!

I believe the Vienna was around 3.1 ˚L and Munich was something like 7.8 ˚L.

How are there two different times on FWH additions?

Recipe fixed. #xmlproblems

Great review!!

Two more things: I don’t understand how two hops can be first wort with a different time 🙂

And second, technical question, do you remove the poppets before transferring from the fermenter to the kegs? If no, have you ever had a stuck transfer? I’m struggling to find the Correct Way—especially since I’m fermenting in kegs.

Cheers!

Recipe fixed.

I don’t remove the poppets, just use a liquid disconnect and a gas depressor to allow constant flow.

The hop additions at 15 and 30 mins have a FWH purpose? I would have assumed bitter and aroma?

For some reason, exporting XML files sometimes creates issues. It has been fixed.

I am puzzled by how low the pH came out on these beers. Having very soft Seattle water I do observe lower pH readings with a majority Munich or Vienna malt beer but these numbers are extremely low compared to my results. Why not add slaked lime or baking soda to adjust into the normal range of 5.2 to 5.5. Assuming these are room temp numbers these are unusually low. Also why is the mash temp so high? I think a 148 to 151F mash would be preferred to evaluate the performance, flavor and fermentablity of the malts. Last I do not know why 60F would be used to ferment lagers? It seems very unusual and could produce esters and other flavors that mask the subtleties of each malt

New to Brulosophy huh? Your list of questions reads like the index of the exbeeriment’s page. Take a look through some of the older exbeeriments, especially the fermentation temp experiments. It should be enlightening.

General Question on FG and mouth feel: I’ve been lead to believe through various articles and books I’ve read that FG and mouth feel can be closely related. I’ve been trying to use the predicted FG in beersmith as a tool to help predict mouth feel when creating my recipes (although I usually see lower attenuation). Do you think this is a useful tool? Also, what FG range would you consider to have a medium mouth feel and full mouth feel? Keep up the great work! 🍻

In my experience the relationship between FG and mouthfeel is more complex than what you’re describing. I’ve tasted beers that finished below 1.010 that had a denser mouthfeel than beers that finished ~1.017 (different styles).

Anecdotally, I have observed a correlation between % of crystal malts and mouthfeel, but I think that’s overly simplistic too. FWIW though, my wife swears there’s a direct correlation between crystal malt and breath stinking, and I have a harder time refuting that one.

My guess is that mouthfeel can be significantly influenced at many stages of brewing (recipe, mash process, yeast choice and fermentation). If you can find a way to model that relationship with some predictability/repeatability, I’d love to hear about it.

Check this out: https://brulosophy.com/2015/10/12/the-mash-high-vs-low-temperature-exbeeriment-results/

Thanks Marshall. Sorry, if it wasn’t obvious I was commenting on Will’s reply about mouthfeel. My experience is similar to your xBMT on mash temp — I couldn’t really tell much difference based on FG or mash temp alone.

I’m curious about the crystal malt percentage as it relates to mouthfeel. I don’t think there have been any xBMT’s on that yet, but at least anecdotally I feel like there’s a correlation.

I’ve also been toying with mash temps, and I have tasted very dry beers that ended over 1.020! IMHO, much more important than FG is if there are any simpler sugars around. A small amount of simple sugars make a beer taste very big, full and rich but a large amount of unfermentable sugars don’t really seem to do as much as you’d think.

I work at a brewery in Germany and the Brewmaster told me that a classmate of his (from brewing school) took a job at Weyermann after their studies and this classmate apparently told my boss that the Vienna malt is just Munich 1 blended off with their Pale Ale. Could have been bullshit, obviously, but why would he lie about something like that. I’ll ask my boss about it again today.

Interesting.

So, my boss confirmed that was what his former classmate told him. Apparently, Weyermann just blend off a base malt (he couldn’t remember if it was Pale or Pils) with Munich until the blend reaches the correct EBC. To speculate further, their Barke line consists of Pils, Munich and Vienna. Coincidence?

Fascinating.

On a tour of the Stamag maltings in Vienna, the maltser told us that nowadays Vienna is a blend of Munich and Pilsner. We were surprised about this but he insisted this was the case everywhere. I assume he was referring to maltings in the German-speaking world. I asked some brewers about this after, and one of them said that he had heard this before from another brewer.

You could probably observe if Vienna is a blend of malts, no?

Thank you. I have a couple of pounds of Vienna around. Maybe next time I brew I’ll just sub it for Munich.

As some have alluded to that modern Vienna is just a mix of munich and pilsner I took the liberty to figure out about the percentages. To simulate Vienna (3 srm) it would be about 16% Munich Light (9.5 srm) and 84% Pilsner malt (1.7 srm).

This is based on Avangard malts.

For years I have used 100% Durst Munich dark malt which is 40° EBC, roughly 20°L, for my Dunkles, using a single pseudo-decoction. This gives me a perfect ringer for the best I’ve had in Bavaria. I wish that Weyermann produced this dark a malt. Surely historically a single malt would have been used. I cannot easily get Durst any longer, so for my last brew I used 100% Weyermann dark Munich to see how it turned out, knowing it wouldn’t be a real Dunkle. Sure enough, it’s a dark amber Märtzen in style. Nice enough, but not the rich liquid bread I like. I’ll go to the necessary trouble to get Durst in the future.

I brewed a single malt Munich a few months ago and THEN read that it contains a fairly low diastatic power, so I added honey late in the fermentation to preemptively dry it out, as I was afraid of too much body for the ABV. It seems to jive that Vienna contains some amount of pils/pale, thus achieving higher attenuation. Even with the honey drying things out, the Munich had a ridiculously heavy feel to it. I am surprised that was not obvious side by side with the single malt Vienna. Stumper

Why do I keep seeing the gravity readings being reporting in these articles as above the meniscus? Case in point, the picture in the article for Vienna has reported FG of 1.010, but reading this according the picture and using the bottom of the meniscus would be 1.011 or even 1.012. Are you adjusting for temp or other things and not just mentioning this? Many thanks for the clarification!

My hydrometer states upper meniscus…

Then for YOUR hydrometer use the upper meniscus. For the people who have a hydrometer which states to use the lower portion of the meniscus they should use that.

And so follows for the hydrometers calibrated at 60F vs 68F and so.

For the people who have a hydrometer which states to use the upper portion of the meniscus they should use that. If YOUR hydrometer states to read from the lower portion then that is where you take your reader from.

And so follows for the hydrometers calibrated at 60F vs 65F vs 68F and so.

Though opinion, I feel it is more more import to be consistent than what the actual number is when we are talking a difference of say 1.050 vs 1.052. Especially for a side-by-side; they are read the same way for comparison.

If Vienna malt (when used with Pilsner malt) is essentially 1/6 that of Munich malt, would a Pilsner made with Pilsner malt along with 12 ounces of Vienna malt, taste exactly like a Pilsner made with Pilsner malt along with 2 ounces of Munich malt? Might be an interesting experiment.

Did you read the article? People already have trouble picking the malts apart even when used at 100%.

Thanks Brulosophy! I was planning to brew my house pale ale this weekend but it features 12% Vienna malt and I just realized I was all out. I was worried I wouldn’t be able to brew without an inconvenient trip to the store–but after reading this exbeeriment and the comments here, particularly about modern Vienna being just a mix of Munich and pale malt, I’m going to just substitute a smaller amount of Munich which I happen to have on hand. I’m happy I vaguely remembered reading this exbeeriment earlier–it saved my brew day!

Marshall, can you post the Brut IPA recipe that you were raving about in the podcast? I am casting about for a good one. I want to brew a Brut with Nelson Sauvin to make a winey beer my wife and I can drink together.

Hey Keith,

I’m working on getting it from Jordan and plan to share it with our Patrons!

would love to see a session on one beer being 100% vienna malt, and 1 beer being 80/20 pilsner and munich 1 to test the notion that maltersters are not making Vienna but just blending Munich I and Pilsner and selling it as vienna malt.