Author: Marshall Schott

Back in March of 2013, before Michael Tonsmeier’s American Sour Beers was released to the public and maybe a month or so after discovering Milk The Funk, I decided to try my hand at making a classic sour beer. Inspired in large part by Mike’s The Mad Fermentationist blog as well as the handful of delicious commercial examples I’d recently tried, my goal was simple– brew an at least passable Flanders (or Flemish) Red Ale.

Back in March of 2013, before Michael Tonsmeier’s American Sour Beers was released to the public and maybe a month or so after discovering Milk The Funk, I decided to try my hand at making a classic sour beer. Inspired in large part by Mike’s The Mad Fermentationist blog as well as the handful of delicious commercial examples I’d recently tried, my goal was simple– brew an at least passable Flanders (or Flemish) Red Ale.

The Beer Judge Certification Program (BJCP) describes the Flanders Red Ale style as:

A sour, fruity, red wine-like Belgian style ale with interesting supportive malt flavors and fruit complexity. The dry finish and tannin completes the mental image of a fine red wine.

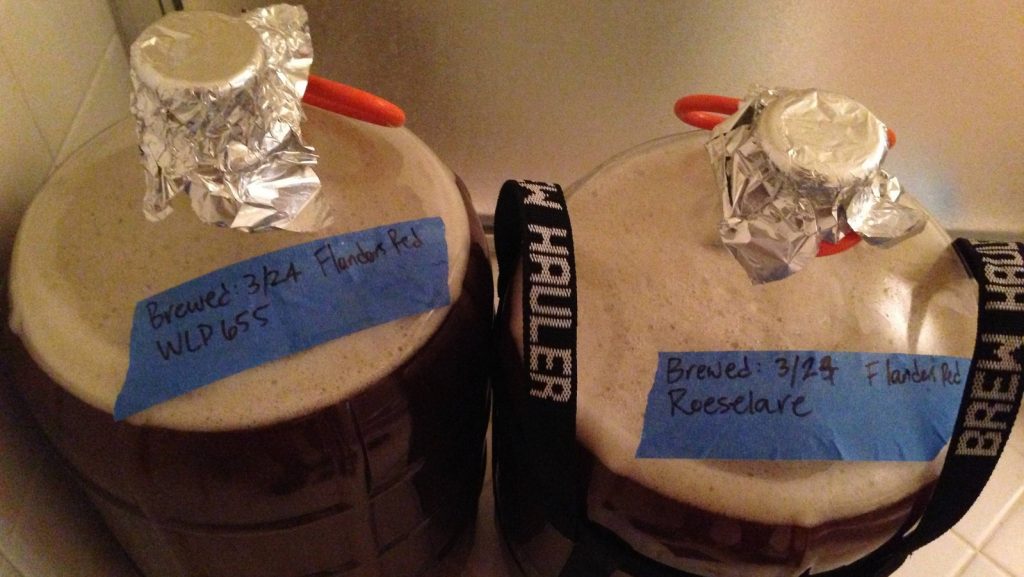

This being my first attempt at making a sour beer, I figured splitting 10 gallons of wort and pitching each with a different mixed culture would increase my odds. I settled on the popular Wyeast 3763 Roeselare Belgian Sour Blend and White Labs WLP655 Belgian Sour Mix 1, which I’d not heard nearly as much about.

Of the myriad approaches to sour beer fermentation I’d read about, I chose the one I thought sounded the best based on what it was I was hoping for in these beers. Both Roeselare and WLP655 contain Sacchromyces and Brettanomyces yeasts as well as lactic acid producing bacteria including Lactobacillus and Pediococcus. I opted against propagating these cultures in a starter due to concerns of pitching so much yeast that the bacteria would require too much time to create the acid levels I was after.

Brewing The Beer

The recipe I designed for my inaugural sour was influenced largely by other Flanders Red Ale recipes I found online as well as the grains I had available in my garage at the time.

Temporality²

Recipe Details

| Batch Size | Boil Time | IBU | SRM | Est. OG | Est. FG | ABV |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 10 gal | 60 min | 16.9 IBUs | 14.2 SRM | 1.056 | 1.015 | 5.3 % |

| Actuals | 1.056 | 1.009 | 6.2 % | |||

Fermentables

| Name | Amount | % |

|---|---|---|

| Pilsner (2 Row) Canada, Superior | 9 lbs | 42.23 |

| Munich Malt - 10L | 5.185 lbs | 24.33 |

| Vienna Malt | 4 lbs | 18.77 |

| White Wheat Malt | 14 oz | 4.11 |

| Caramel/Crystal Malt - 60L | 12 oz | 3.52 |

| Honey Malt | 12 oz | 3.52 |

| Special B Malt | 12 oz | 3.52 |

Hops

| Name | Amount | Time | Use | Form | Alpha % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Goldings, East Kent | 32 g | 60 min | Boil | Pellet | 6.4 |

Yeast

| Name | Lab | Attenuation | Temperature |

|---|---|---|---|

| Wyeast Roeselare OR WLP655 Belgian Sour Mix 1 | 80% | 55°F - 80°F |

Notes

| WLP655 = 1.009 FG (6.2%) Roeselare = 1.013 FG (5.6%) |

Download

| Download this recipe's BeerXML file |

It was March 24, 2013, the day before my 32nd birthday, that I decided to brew my very first sour beer. Joined by my brother-in-law, Joe Schmidt, we made wort, a process no different than I’d done so many times before.

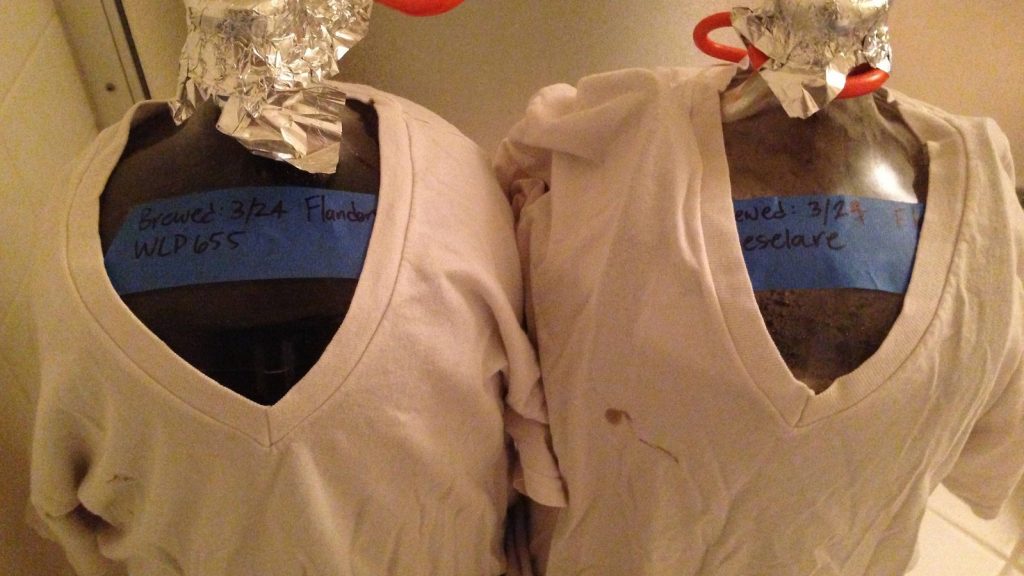

The brew day went off without a hitch and I ended up with just over 10 gallons of chilled wort with a strikingly red hue. Undoubtedly inspired by fears of oxygen permeability, I pulled a couple old 5 gallon glass carboys out of storage, gave them a good cleaning and sanitizing, then racked equal amounts of wort to each one. It was still relatively cool out at the time, and since I didn’t want to tie up a fermentation chamber for a year or more, I placed the filled carboys in the shower of my guest bathroom.

Into one batch I pitched a single vial of WLP655 Belgian Sour Mix 1 while the other was hit with a fully expanded smack-pack of Wyeast Roeselare, both quite fresh. When I returned the following night, I noticed the WLP655 beer looked untouched while the batch pitched with Roeselare had developed a rather hefty kräusen. At this point, I covered each carboy and eventually swapped out the foil with airlocks.

Then I left the beers alone, for a long time… without racking them to a secondary. I know, crazy, but it was a decision I made based on what may have been my first interaction with Michael Tonsmeire. At some point before or just after brewing the beer, I reached out to Michael to ask about the practice of leaving Belgian sour beers in primary until packaging, as I’d read conflicting reports from brewers, some saying leaving it on the yeast cake leads to autolysis flavors and others claiming racking to secondary negatively impacted the sour character. Michael tipped my decision when he told me that “aging in primary produces a more complex-funky-rustic-minerally flavor as the Brett ferments the sugars and fatty acids released by the dying primary yeast.” Go big or go home, eh?

I peaked in on the beers every once in awhile just to see how things were progressing, but the bungs were never removed, the most I did was top-off the airlocks with water. My ability to leave them alone was in no way proof of how patient I am and was driven wholly by my fear of ending up with a beer that tasted like vinegar. They just sat in my shower the whole time, the ambient temperature ranging from 66°F/19°C to 74°F/23°C, alone and untouched.

It wasn’t until 8 months after brewing that I decided to dip into the beers for a taste. Joe was back in town with his family for Thanksgiving, we’d had a few beers, and I thought having him there for the first sampling would be cool since he helped brew them. Using a sanitized turkey baster, I very quickly pulled a few ounces from each batch, making sure to introduce as little air as possible and replacing the airlocks within seconds. The beers in the carboys looked identically still, neither had developed a pellicle, which indicated to me my oxygen reducing efforts were working.

The WLP655 had a cleaner aroma, slightly sharper with less overall pizzazz than the Roeselare beer, which had a notably more funky nose. The flavor matched the aroma for both batches. I was pleased with where the Roeselare batch was headed but wanted to give it more time to develop its acidity. I recall feeling somewhat disappointed with the WLP655 beer– “this after 8 long months?!” That’s when I decided to engage in a practice I’d heard of others doing to encourage more character out of otherwise pallid sour beers. I’d picked up 3 sours from Russian River Brewing to enjoy with Thanksgiving dinner, the dregs of each ended up in the WLP655 beer. Over the following 2 months, I pitched the dregs from 4 Bruery sours and 2 more Russian River sours in hopes of creating something uniquely tasty. Fingers crossed.

Two months later, both beers looked much more like the pictures I’d seen seen of sour beer fermentation on the internet, fuzzy white with bubbles blanketing the top. I pulled samples again in March of 2014, a year after the beers were brewed. It was clear that pitching commercial dregs had worked, as the WLP655 beer had taken on a much more assertive acidity, though it wasn’t quite where I wanted it. The Roeselare beer was still much more funky than sour, which wasn’t bad, but I decided to give it a little more time as well.

On April 12, 2014, another tasting revealed the WLP655 beer was right where I wanted in terms of acidity, and while the Roeselare beer was progressing, I felt it required another few weeks. I’d decided long before this point that I wasn’t going to bottle condition these beers because I like the control over carbonation kegging affords and I wanted to start drinking sooner than later. I racked the warm WLP655 beer into a keg, purged the headspace a few times, set it in my keezer on 20 psi of CO2, then left it alone to carbonate. After 5 days, I reduced the gas to serving pressure and pulled a taste, my first time trying the finished version of my first Flanders Red Ale.

The notes I took from that initial tasting indicate the beer was better than I expected based on samples from the primary, but not as characterful as commercial examples. I recall it having a thinner mouthfeel than I thought it would given the grist, it was almost refreshing and crisp, especially for a 6% ABV beer. The acidity played a starring role, though there was a nice malt character that held the tartness up nicely. “May keep on tap and drink quickly” was the last thing I wrote down. I did end up sharing this beer with a few friends fresh-off-the-tap, but only in taster glasses, as I ultimately settled on bottling a bunch up.

I sampled the Roeselare beer on May 4, 2014, it was spot on, so I proceeded to keg it.

Not wanting to dedicate 2 taps to sours, I bottled the remaining WLP655 beer, which had carbonated to a predicted 2.7 volumes. There was enough beer left to fill 46 standard 12 oz bottles, which I placed under a bay window seat in my son’s bedroom– dark, relatively stable temperature, and hidden enough so that I wouldn’t feel tempted to grab one or six at random. The full keg of Roeselare beer then replaced the WLP655 beer in my keezer. Hydrometer measurements taken at kegging showed the WLP655 beer attenuated 0.004 SG points lower than the Roeselare beer, something I chalked up to the additional bacteria from all the commercial dregs.

I performed the same carbonation routine on the Roeselare beer as I did the WLP655 beer, pulling the first cold and carbonated sample 5 days later.

I really enjoyed this beer upon first taste. “More oomph, funky with balanced acidity, not as tart.” I let this beer condition cold in my keezer for a little more than a month before filling 46 bottles; I hadn’t touched any of the WLP655 bottles, so I had equal amounts of each.

Impressions Over Time

Over the following few months, I shared a couple bottles with friends who appreciate sour beers, pulled a few out during holiday dinners, and occasionally popped one open to enjoy by myself. I never entered either of the beers in competition, mostly because I never thought to, but also because I don’t get much out of competing. However, I did jot down some notes while drinking these beers at certain points in hopes of tracking their progression.

November 27, 2014 | Beer Age: 1 Year 8 Months

Having only sampled one of each beer since they were bottled in May of this year, I was excited to share them with co-brewer Joe and some other friends at a Thanksgiving gathering at my place. The occasion was made all the more fitting since Joe’s last taste of these beers was exactly 1 year prior, the point at which I’d decided to pitch commercial dregs into the WLP655 batch. Sitting around my kitchen table, we poured tasters of both beers next to each other for comparison.

According to my notes, the beers tasted as I remembered them from the keg, nothing strikingly new, which on many levels was a good thing, as I was concerned the bottling process would have produced some oxidation character. The WLP655 beer was noticeably cleaner and tart than its Roeselare counterpart, “like sour cherry juice with hints of Brett funk.” The Roeselare beer was more “full-flavored” with lower acidity and while I still perceived notes of cherry, it also had flavors of “raisin” and “a very slight hint of acetic,” which I’ve come to expect from Roeselare.

June 11, 2015 | Beer Age: 2 Years 3 Months

I took a couple bottles of each beer to the 2015 National Homebrewers Conference in San Diego, CA to share at the Milk The Funk meet-up. Again, the feedback from others was generally positive. Michael Tonsmeire agreed that the WLP655 beer was a bit one-dimensional while the Roeselare beer had more going on, which led to a conversation about the impact of wood aging and blending to improve sour ales. I pecked out a few impressions on my phone immediately after the meet-up.

Much like Michael, I felt the WLP655 beer was pretty simple for what’s typically a more complex style of beer, though it didn’t seem terribly different than prior samplings. The Roeselare beer definitely had more going on relative to the WLP655 beer, though it almost seemed to have lost some complexity. I noted the beers were consumed pretty soon after taking them off ice, so it’s likely the coldness influenced my perception.

August 30, 2017 | Beer Age: 4 Years 5 Months

I’ve definitely had a few bottles of both beers over the last 2 years, I know this because I currently only have 6 bottles left of each in my stash, but I failed to document my impressions for one reason or another. Over the weekend, I tossed a bottle from either batch in my fridge to chill for a final focused review.

| WLP655 Belgian Sour Mix 1 | Wyeast 3763 Roeselare | |

| Appearance | Slightly hazy, which could have contributed to the beer looking more brown than earlier tastings, when it appeared red. Low lying off-white head sticks around pretty long for a sour. | Decent clarity with only minimal chill haze (faded as it warmed). Color was notably more red than WLP655 beer. Off-white ring of foam hung around the entire time. |

| Aroma | Bag of overripe Tulare cherries with a whisper of mulling spices, crusty bread, and barely a hint of vinous character. Nothing offensive, quite pleasant, smells like a sour ale. | Cherry jam spread over a thin layer of cream cheese on toasted sourdough bread. Very faint hint of overripe tropical fruit that’s about to rot and a box of old books my grandma gave me. |

| Flavor | Tart cherry juice explodes on my palate then fades surprisingly quickly to leave a moderately lingering mineral flavor that borders on metallic. Acidity is the feature with the other characteristics playing a very distant supporting role. Minimal, almost unnoticeable, Brett funk. | Prune juice and dried cherries up front followed by an assertive fruity tartness that lingers forever on my palate. Reminds me of a rich Merlot, even has hints of oak. Much more tart than in prior tastings, though balanced well by flavors from the malt, yeast, and bacteria. |

| Mouthfeel | Upon initial sip, I thought I perceived a medium body, but once the flavor fades, it’s clear the beer is quite thin and watery. Nice carbonation made the beer easy to drink. | Medium body and surprisingly creamy. No noticeable astringency when accounting for acidity. Mouth is left feeling clean despite the lingering flavor of the beer. Quite nice. |

It’s probably obvious which one I prefer most. The beer pitched with Roeselare just had more of the characteristics I expect in a good Flanders Red Ale, from its overall complexity to the rich mouthfeel. Where the WLP655 beer was borderline insipid, the Roeselare beer was interesting and fulfilling, each sip making me want to come back for another to see what else I might discover. I was pretty surprised with the acidity development in the Roeselare beer, it took some time, but the time did the trick. Whereas the Brett character in the WLP655 beer was, like Baby, put in the corner, the Roeselare beer has a solid blend of funky and fruity characteristics that made it immensely more appealing to me.

Conclusions

I don’t mean to get too sentimental, but as I sat there finishing the 4 year old versions of each of these beers, I couldn’t help but consider how life was at the time they were brewed and all that’s happened since. My youngest daughter, Olive, was born on July 4, 2013, 4 months after this beer was brewed. My other kids, Hazel and Roscoe, weren’t in school at the time and just last week started 3rd and 1st grades, respectively. Brülosophy didn’t exist. I’d yet to meet Jersey & Tim, who likely had yet to ever review a craft beer. In the 4 years these Flanders Red Ales have been around, things have changed– homebrewing, craft beer, the world in many ways, my idea of “free time” and how I spend it. Indeed, what I love most about these beers has little to do with how they actually turned out, but rather the fact they serve as a tangible reminder of the temporariness of a moment.

Of course, this experience also spurred some less cheesy, more mechanical thoughts…

While I’m not sure I did anything wrong with the Flanders Red Ales I made, or even if I could have done anything different to make them better, I’d be lying if I said either incited the orgasmic organoleptic experience I was hoping for. The Roeselare batch was quite good, the WLP655 beer wasn’t terrible, but as a dude for whom impatience is a daemon, I’ve little issue acknowledging it really wasn’t worth the time.

I only say this now because of the explosion of methods to make delicious sour beers in massively abbreviated times. The quick sour beers I’ve sampled, which have included many versions of classic styles like Flanders Red Ale, have not only been passable, but I’d contend better than any of the long aged sours I’ve made. Matt and crew from Mellow Mink Brewing as well as my friend Sean Wood who is managing the sour program for House Of Pendragon are making fantastic sour beers that they’re turning around in as little as 5 weeks. Sure, quick souring loses points in the classically romantic department, but for me, it’s taste that matters, and for that reason alone, I doubt I’ll ever use such a drawn out souring method again.

If you have thoughts about this article, please share them in the comments section below!

Support Brülosophy In Style!

All designs are available in various colors and sizes on Amazon!

Follow Brülosophy on:

FACEBOOK | TWITTER | INSTAGRAM

If you enjoy this stuff and feel compelled to support Brulosophy.com, please check out the Support Us page for details on how you can very easily do so. Thanks!

13 thoughts on “A Tale of Two Sours: Reviewing 4 Year Old Flanders Red Ales”

Some friends and I have a Flanders Red Solera in progress. I’m glad you wrote this as it gives me some ideas for our next pull and addition but I do wish the 655 had not been added to as that is the yeast we are using. Thanks for you time in writing this and your thoughts.

Oi, moving text. 🙂 Say, would you care adding some pointers on methods to brew a flanders red in 5 weeks? Would love to do that!

Cheers!

I’ve never made a quick sour Flanders Red, but I’ve had a few that were very delicious. I’d recommend checking out Milk The Funk and Sour Beer Blog for pointers from people who actually know what they’re talking about.

Wait, you want a Flanders Red that goes grain to glass in five weeks or in five weeks, you will brew a beer that’s a Flanders Red?

Ahah, my, both in fact 🙂

Damn good article. Thank you for sharing.

I love flanders red; its my favourite style. I have a solera of it on the go at all time – fermenting solely with Roeselare. I’ve found that Roeselare behaves well in the solera and if you love the reds, its a good way to ensure a continued supply.

Sounds like a blend of these 2 beers would have yielded some additional complexity. Aren’t most traditional (i.e. not kettle) sours blended to achieve a final desired taste/tartness? The fact that you described one as more acidic but less complex, and the other as more funky but less tart – I was waiting for the paragraph where you said you blended them and it was perfect, but it never came!

So, I did blend them, and it wasn’t perfect… so I figured it wasn’t really worth mentioning.

It’s reading stuff like this that makes me want to completely quit every style that doesn’t take or get better after a year. Nothing but RIS, Barleywine, Quads, and Wild Ales from here on out? Not likely. Still, the magic of time–both in beer and life–is to be savored whenever possible.

Thanks.

Terrific writeup man. Made me think back to what I was doing 4+ years ago. My wife and I were new parents of twins, trying to figure out how to take care of another small human, and how to keep homebrewing alive as a hobby. Wish I would’ve had the forethought to do something like this back then!

That’s interesting that an early tasting yielded a thin tasting beer despite what should have been an interesting grain bill. I’ve brewed two Flanders Reds, based on two different recipes, both fermented with Roeselare and aged with oak cubes. The first was horrible, in that it tasted like water with only a hint of sourness. (Where the heck did all of the grain bill’s flavor go??) The second has more flavor but took on FAR more oak than desired, to the point that it’s just about undrinkable. (I also threw in some accelerator dregs into the second batch, which perhaps helped the flavor development?) I tried blending the two (50/50) but the result was no good, still too oaky. I was going to just dump them all, but the process of pulling the cages and corks was enough to convince me to just toss them back into a cold closet and sit on them a few more years. Maybe — hopefully — they’ll turn into something drinkable.

Since I’m at 0 for 2, I like the idea of quick sours so I can figure out immediately if something is going to work rather than letting it sit for years in carboys and bottles only to dump it later.

I recently have been getting into sour beers now that I’ve moved down to Charleston, SC where the craft brew scene has been booming. I first got introduced to sours out at this local brewery out on Johns Island called Low Tide Brewing. After that, I instantly became obsessed with finding the best sour beer in Charleston, but Low Tides Carolina Creamsicle has been my steady favorite. Because of this hunt, I’ve been toying with the idea of starting my own home-brewing journey with sours in an attempt to replicate these flavors when I leave Charleston in a few short months. Do you have any tips for getting started with home-brewing, especially beginning with sours in home-brewing? Any tips are highly appreciated!