Author: Matt Del Fiacco

I’ve been watching IPA trends with great interest. While I don’t tend to brew IPA much myself, I’m incredibly interested in the methods brewers use to extract hop aroma and flavor without the accompanying bitterness. The pursuit of strong-but-soft hop quality characteristics of hazy NEIPA points to hop additions occurring later in the boil as being crucial to achieving this sought after character, as it reduced the isomerization of alpha acids while also allowing for less time to drive off other essential hop oils.

An increasingly popular method of imparting a beer with as much hoppy goodness as possible is the hop stand, a post-boil hop addition that occurs prior to chilling the wort to pitching temperatures. The general idea behind this method is that a wort temperature of around 170°F/77°C will allow for the extraction of desirable flavor and aroma oils from the hops without isomerizing the alpha acids, thereby reducing what they contribute to bitterness.

The thing about hop stands is that there are myriad approaches brewers can take, from adding a dose of hops immediately at flameout and letting them sit for a specific amount of time to chilling the wort to a certain temperature before adding the hops and letting them rest. With a prior xBmt comparing hop stands occurring at either flameout or 170°F/77°C returning non-significant results, I couldn’t help but wonder if an even lower temperature might make a difference. In theory, wort temperature at flameout is still hot enough to isomerize alpha acids, but surely there has to be a point where only hop oils are extracted without bitterness. Indeed, an experiment performed by the Experimental Brewing IGORs indicated tasters were capable of distinguishing a beer with a flameout hop stand from a similar beer where the hop stand occurred once the wort was chilled to 120°F/49°C, even when accounting for potentially flawed data. Would this be something I could replicate? I was curious to find out!

| PURPOSE |

To evaluate the differences between beers where the hop stand additions were made at either flameout or once the wort was chilled to 120˚F/49˚C.

| METHODS |

Since this batch doubled as a Hop Chronicle beer, I went with a simple American Blonde to let the hops stand out.

Look Me In The Eye Hoppy Blonde Ale

Recipe Details

| Batch Size | Boil Time | IBU | SRM | Est. OG | Est. FG | ABV |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5.5 gal | 60 min | 25.4 IBUs | 3.6 SRM | 1.043 | 1.011 | 4.3 % |

| Actuals | 1.043 | 1.005 | 5.0 % | |||

Fermentables

| Name | Amount | % |

|---|---|---|

| Pale Malt, 2-Row (Rahr) | 8.375 lbs | 94.37 |

| Carahell (Weyermann) | 8 oz | 5.63 |

Hops

| Name | Amount | Time | Use | Form | Alpha % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Medusa | 16 g | 60 min | Boil | Pellet | 3.8 |

| Medusa | 21 g | 30 min | Boil | Pellet | 3.8 |

| Medusa | 40 g | 15 min | Boil | Pellet | 3.8 |

| Medusa | 33 g | 20 min | Aroma | Pellet | 3.8 |

Yeast

| Name | Lab | Attenuation | Temperature |

|---|---|---|---|

| Flagship (A07) | Imperial Yeast | 75% | 60°F - 72°F |

Notes

| Water Profile: Yellow Bitter in Bru’n Water Spreadsheet |

Download

| Download this recipe's BeerXML file |

A couple days before brewing, I spun up a starter of Imperial Organics A07 Flagship yeast that would later be split between the batches.

I was in the middle of moving during this brew day, so my parents graciously allowed me to set my stuff up in their backyard so I could knock this xBmt out.

I adjusted RO water with minerals then weighed out and milled the grains while it was warming up to strike temperature.

With the water heated, I dropped mashed in, briefly stirring gently before turning on the pumps for recirculation.

After letting the mash settle for a couple minutes, I confirmed I’d hit my intended mash temperature.

After the 60 minute mash, I removed the grain from the wort, allowing it to drip into the kettle as I began heating the wort.

At this point, I measured out equal amounts of hops for both batches.

Once a boil was reached, hop additions were made at the times stated in the recipe.

After 60 minutes, I cut the heat to both batches and immediately added the flameout hop addition to one batch and let it continue to recirculate without chilling. For the other batch, I quickly chilled the wort to 120°F/49°C, set my controller to maintain this temperature, then added the hop charge and turned the recirculation pump on.

I let both batches “stand” for precisely 20 minutes before chilling to my desired pitching temperature, after which they were racked to fermentation kegs.

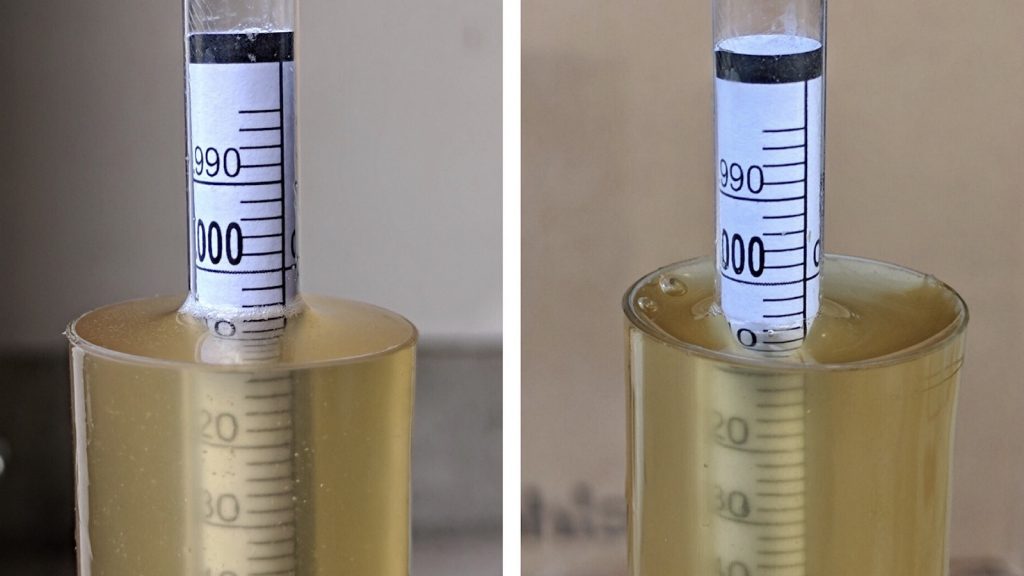

Hydrometer measurements at this point confirmed both batches were sitting at the same OG.

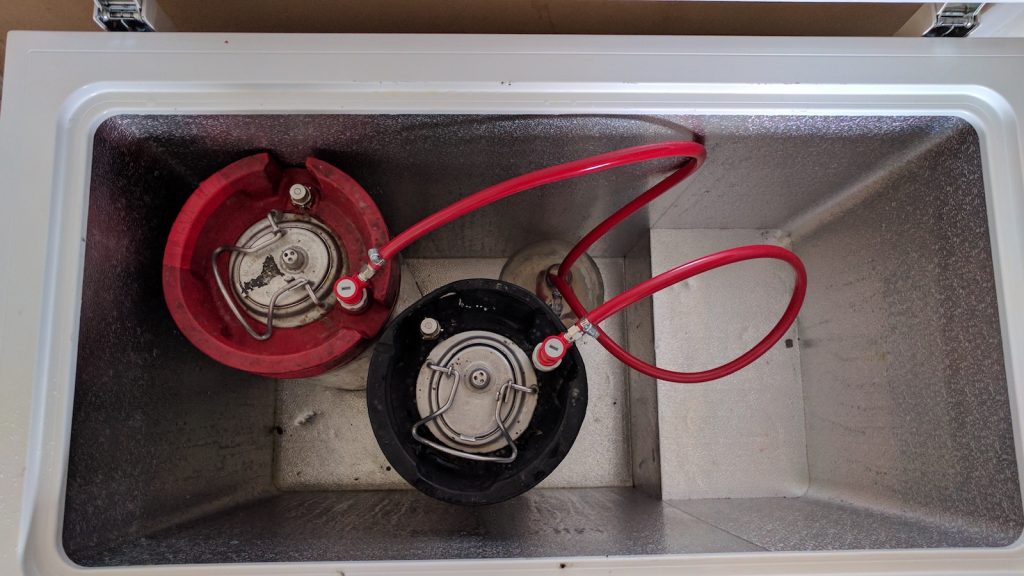

I placed the fermentors next to each other in my temperature controlled chamber, attached blowoff tubes, and pitched the yeast.

After a week of vigorous fermentation activity, dry hops were added to each batch and they were left 3 more days before I took hydrometer measurements indicating FG had been reached.

I cold crashed, fined with gelatin, then pressure transferred the beers to serving kegs.

After a period of burst carbonation, I reduced the CO2 to serving pressure and let the beers condition for a few days before serving them to participants. Even after an additional week of cold conditioning, they never dropped clear, which I’ve seen before in hop stand beers.

| RESULTS |

A panel of 22 people with varying degrees of experience participated in this xBmt. Each taster, blind to the variable being investigated, was served 2 samples of the beer where the hop stand occurred at flameout and 1 sample of the beer with a 120°F/49°C hop stand in different colored opaque cups then instructed to select the unique sample. At this sample size, a total of 12 (p<0.05) correct selections would have been required to achieve statistical significance, though only 9 tasters (p=0.29) chose the different beer, indicating tasters were unable to reliably distinguish a beer made with a flameout temperature hop stand from one where the hops were added at 120°F/49°C.

My Impressions: I went into my own blind triangle tests with shaky confidence, and sure enough, even having sampled both beers numerous times, I just wasn’t able to tell them apart consistently. Over 4 attempts, I was only correct twice, and I admit those both felt like random guesses. Overall, the beers had a lot of hop character, which I perceived as being quite dank with hints of tropical fruit and apricot. The malt presence was pretty soft. I really enjoyed both beers, neither had a harsh bitterness, and both were full of delicious hop character!

| DISCUSSION |

Based on the conventional wisdom, adding a charge of hops immediately at flameout when the wort is still near boiling temperature ought to result in a beer with a higher level of bitterness compared to adding the hops to cooler wort. Moreover, performing such a hop stand in cooler wort should, or at least is believed by many to, restrict the volatilization of delicate hop oils, thereby resulting in a beer that’s not only less bitter, but more aromatic and flavorful. However, the fact participants in this xBmt were unable to reliably distinguish a beer where the hop stand was performed at flameout from one where hops weren’t added until the wort was 120˚F/49˚C calls this wisdom into question.

I can’t say for sure what’s going on here, and I certainly didn’t expect these results, but I have a few theories. First off, the fact the level of bitterness between the beers didn’t immediately give it away suggests that isomerized alpha acids from kettle hop additions may contribute a similar quality of bitterness as non-isomerized alpha acids from hops added as after the boil. After all, hops are bitter, as anyone who has been silly enough to eat a raw pellet knows, and that bitterness goes somewhere when added to even cool wort or beer. Ultimately, the beers in this xBmt received the same amount of the same hops, and while the calculated and maybe even actual IBUs were different based on wort temperature, it would seem that difference wasn’t large enough to impart a noticeable difference. The second and perhaps even more confounding thing about these results is the fact the cooler hop stand beer wasn’t noticeably more aromatic and flavorful than the flameout hop stand beer, suggesting volatilization occurred at a similar rate in both. Is it possible hop stands at cooler temperatures, at least on the homebrew scale, are no more beneficial than tossing hops in at flameout or maybe even during the boil?

Despite these results, my inclination is to continue dropping the temperature of the wort when performing hop stands in hopes that I ward off as much bitterness as possible. Even if it doesn’t make a difference, it’s an easy enough practice that continuing to do it doesn’t change much about my brew day, though if ever I’m pressed for time, I certainly won’t hesitate to toss my hops in at flameout.

If you have thoughts about this xBmt, please feel free to share in the comments section below!

Support Brülosophy In Style!

All designs are available in various colors and sizes on Amazon!

Follow Brülosophy on:

FACEBOOK | TWITTER | INSTAGRAM

If you enjoy this stuff and feel compelled to support Brulosophy.com, please check out the Support Us page for details on how you can very easily do so. Thanks!

32 thoughts on “exBEERiment | Flameout Addition vs. 120°F/49°C Hop Stand In An American IPA”

I’m not surprised by this one. It’s good to have some experimental data backing up my hunch.

Would be interesting to include calculated IBU using either Tinseth or Rager formula in this write-up. I don’t have much experience using such low AA hops in hoppy beers but doubt you hit a reasonable difference in bitterness where that could be useful as an indicator. My hop stand usually looks like 4-6oz of hops with alpha acids ranging from 12-18% in 11 gallons. I believe the bitterness contribution comes from both the flame out hops and the additional time above 180F for my late kettle hops (since they are still in the kettle during the whirlpool).

Do you think the hopstand length is a variable worth varying?

Quite possibly! I think temperature would play a role there as well, definitely on the list.

Maybe there were too many hops in the the boil to get in the way of whatever the whirlpool additions added. Seems like most NEIPA recipes call for very little hops during the boil, even some with just a liquid extract at the beginning, with almost all hops added after the boil. I’d like to see a similar experiment with a single 60 minute addition of magnum or a hopshot and all the medusa hops added after flameout like you did above and then see if people can tell the difference

You mentioned in the article that you added dry hops, but they are not listed in the recipe.

Sorry about that! Typo in the recipe, I’ll get that updated! Great catch, thank you

Matt,

Just think that, for this xbeeriment purpose, I´d skip EVERY SINGLE boil addition and add a large amount for the whirlpool. Than we would have a good test, though. The IBUs from the boil additions could have hidden the difference between the whirlpoll ones.

I myself made to IPAs with just whirlpool. In the first one I add 1/3 at flameout, 1/3 at 90 and 1/3 at 80. The second one was all in 65C. I have to say that, in the second one, I perceived nearly any bitterness, while in the first I did perceived it a lot.

Thanks a lot. That’s really valuable raport.

Just to clarify… you did a blonde ale with a 33g flameout addition, using a 3.8% AA hop, and that was the variable that differed?

Unless I’m misreading this, I can’t see how a hop addition that small would make much of a difference. Increasingly these days, IPA’s are being hit with 1 – 2lb/bbl in the whirlpool (around 3 – 6oz for 5 gallons) or more. I’d be interested in hearing why a very small addition of a very low AA hop, that only comprised 30% of the total additions on the hot side, would ever have resulted in a noticeable sensory difference.

3.8% AA hops is the reason IMO. Try something over 10% like Citra. I make IPA/APA beers probably once a month on average and have never used a hop with that low AA. I would say that low of AA is too little to be Noticed by most people. That has to be the difference IMO.

Love these experiments!

Exactly this. What was the point of only adding 33g of an insanely low AA hop? This exbeeriment needs to be done with something like Citra, mosaic, El Dorado etc and much more than an ounce. I bet adding such a small amount of low AA hop like that directly into the boil wouldn’t have made a detectable difference. I still thank you guys for doing the Lord’s work! Love brulosophy!

yeah, nice work, but i think to be fair we need to see like 3-6 oz per 6 gallons of wort at least in the whirlpool, using typical 12-15% AA hops.

I’m really surprised that you’ve chosen to dry hop your beer for this experiment, as that will likely cover up the target variable. I’d venture a guess that if your removed the dry hops, the aroma of the cooler hop addition would shine through more.

I’m kinda curious now how an experiment would turn out comparing flameout vs. no flameout hops in a dry hopped beer.

I will echo what several of the previous comments have stated. I can kind of understand why a hoppy blonde ale was chosen, but don’t you think a NE IPA where the only non-bittering charge of hops came at either FO or 120 F would have been a MUCH better choice? I’d think the higher the AA% the better for this exbeeriment would have been a good idea too.

Two more comments, is it appropriate to assume that because a previous exbeeriment (with a different recipe) did not produce a significant result when using gelatin fining, that you can use that as a control for every batch of beer ever made again, regardless of recipe? Seems to go against the ethos of the site that each exbeeriment is an n=1 type of thing, right?

Second, would it be worthwhile to use the masses to help guide recipe selection for future exbeeriments, or even what the actual exbeeriment would be? I’d think this would be a great way to drive reader interest as well as mitigate the above described issues.

I really enjoy reading these posts every Mon/Thurs, would just like to see the maximum knowledge output obtained if possible!

Agreed. Also, why use gelatin if it has no effect on clarity for this recipe?

A note on gelatin, they have tested this twice in the past (and several times against other fining agents), both failed to find significance. I think they’re doing the right thing, trying to use a consistent process between all these different brews.

I’m sure they’ll fess up on this, but I’m pretty sure this is also for a Hop Chronicles post. Single hop, relatively standard hopping schedule…

It does seem that dry hopping is a confounding variable here.

That and all the boiled hops

Here is a theory…Matt intentionally picked a whirlpool addition that would not add enough IBU to be discernable. I calculated the whirlpool hop addition probably added about 6 IBU using Beersmith. TBH it probably added more than that because it probably pulled a couple more IBU out of the 15 min addition too but Beersmith doesn’t adjust the 15 min addition when you add a whirlpool. But whatever, less than 10 calculated IBU difference between the batches, which is “internet lore” thrown around to be not easily distinguishable.

So bitterness is not different but why would people add hops at a low enough temperature to run some risk of contamination? Well the proponents of the low temp whirlpool addition do suggest this in order to preserve elusive aromatics coming from low boiling temperature hop oils. So in this experiment he showed that even if he did preserve those low boiling aromatic oils…the panel couldn’t tell. Perhaps at 120 you can’t really achieve anything you don’t also get in a dry hop. So you say dry hopping is a confounding issue…not really. Dry hopping is an accepted low risk practice. The dry hops are added after some alcohol has been generated and the fermenting beer has become a less hospitable (for contaminants) environment. 120F is kind of a scary place. Is that high enough to pasteurize? Not sure.

It is a good enough experiment in providing a reason to me not to bother with a scary to me 120F hop addition. Whatever I could get out of a 120F addition is likely provided by the combination of flameout whirlpool addition and dry hopping.

Ha! Nothing so malicious, I definitely plan on testing this again in a different style, with a larger hop charge.

Regarding the use of gelatin: a lot of NEIPA brewers argue that fining the beer strips it of a lot of important oils, and many swear that it’s only in keeping the hops in suspension that the maximum juiciness is obtained. I would be curious to see the same experiment but without the use gelatin.

I always thought the same, despite all of the XBMTS indicating it might not impact beer flavor. I then did a side by side on a west coast ipa and i couldn’t tell the difference reliably in triangle testing, either could my wife. i’d like to do this on an hazy ipa again sometime and see if i can tell.

Another experiment that proves hop stands are rather a waste of time. Ill be sticking to adding the aromatic, flavorful charge that I would do in a hop stand, to the last 5 mins of the boil and rapidly chilling instead. Dry hopping seems to add even more flavor and aroma. There is no need for a hop stand in my opinion.

I think the amount of whirlpool hops get lost in the recipe you used. A better recipe would be a bittering charge to your intended ibu, then 3 ounces at whirlpool skipping the dry hops. That would be enough late hops to see or not a difference in bitterness aroma or flavor. Regardless, I like the experiment but am not surprised at your results.

I agree with John. Dry hopping very likely covered up any noticeable differences in the two hop stand methods. Either only a bittering charge or even no hops except at the hopstand (blasphemy?!?) would have given me better confidence in the results.

How much volume are you able to ferment in corny kegs? The recipe called for 5.5 gallons but I’m almost certain you can’t ferment that much in the keg.

My average batch in corny kegs is about 4.5 gallons. Most of the recipes I post are scaled for other brewers to be able to utilize, but we go back and forth on that a bit. But my batch size in the corny kegs is 4.5 gallons in the fermenter.

Isn’t 49c quite a low temperature anyway?

For example they say to soak a tea bag at something between 70c and 85c.. I know hops isn’t tea but for me it makes sense that a higher temp is needed to extract the flavours.

I’m also thinking that a ‘staged’ hopstand might be worth a try. E.g. Put in half at flame out, another half 15 mins post flame out for a total hopstand period of 30 mins

I love your experiments and find them quite useful, so, thank you for that. However, I think to TRULY test this, you would have to make an IPA or NEIPA and do it based on a small amount in FWH or 60 minute boil (or however long) and THEN do the whirlpool hops, as various temps to see effect on flavor. But thank you so much for all you do. I find the information invaluable. Cheers and rock on!